Our ancestors traversed Europe earlier than thought.

The excavation of the early modern human (foreground) and Neanderthal layers (background) of Lapa do Picareiro. Credit: Jonathan Haws

Natalie Parletta

New clues continue to unravel the compelling Palaeolithic mystery of modern human movements and the Neanderthal transition, suggesting the two groups overlapped by several thousand years and may have even interacted.

Archaeological evidence points to modern human settlement in westernmost Eurasia around 5000 years earlier than previous estimates, toppling suggestions that Neanderthals prevented our ancestors’ dispersal throughout Europe.

The discovery “shows that modern humans moved rapidly across highly diverse landscapes and adapted to different climates and environments,” explains Jonathan Haws from the University of Louisville, US, lead author of a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Neanderthal populations were probably not very dense and therefore unable to prevent moderns from invading their territory,” he adds.

“It also raises the possibility that the two groups were contemporary and interacted with one another, ultimately leading to the assimilation of the Neanderthals.”

The international team, including researchers across Europe, unearthed stone tools used by our anatomical ancestors 41,000 to 38,000 years ago in the Lapa do Picareiro cave in central Portugal, an area Neanderthals are thought to have occupied 45,000 to 42,000 years ago.

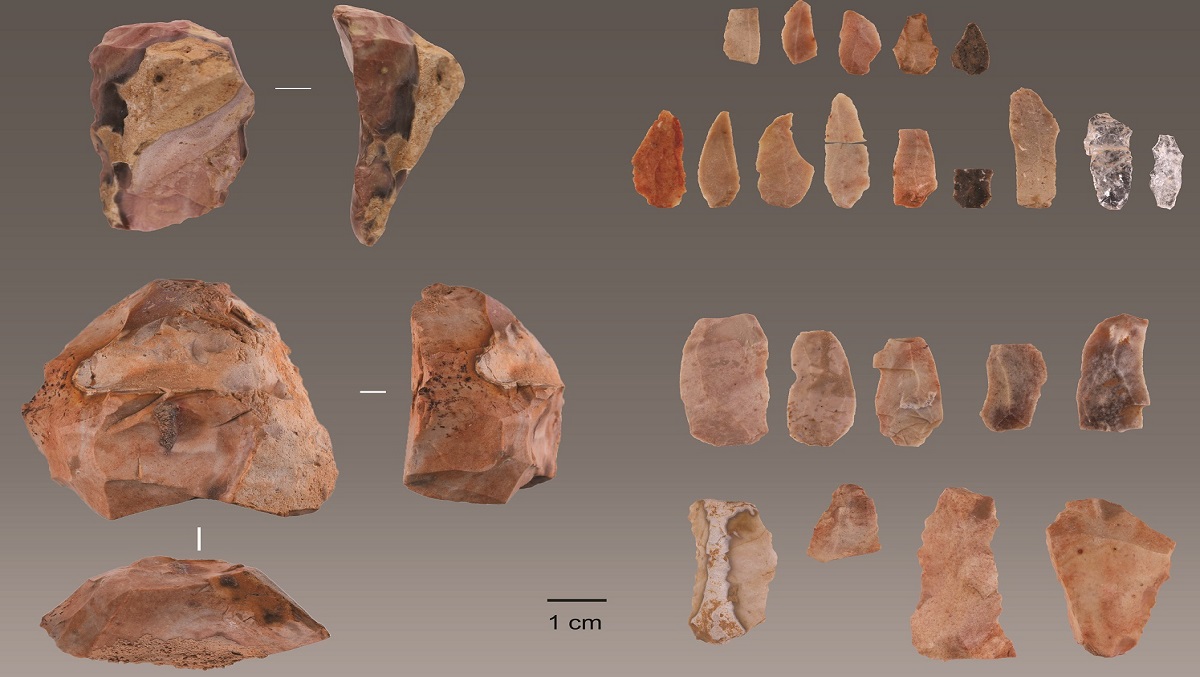

Tools discovered in Lapa do Picareiro in central Portugal. Credit: Jonathan Haws

The tools were Aurignacian period artifacts, technology associated with early modern humans in Europe. The team found them when working through 50,000 years’ worth of well-preserved remains at the site.

Other rich deposits associated with the tools include thousands of bones left from animals that were hunted, butchered and cooked, analysed by Sahra Talamo from Germany’s Max Planck Institute using modern radiocarbon dating techniques.

Similar artifacts have been found in layers of comparable age from northern Spain and southern France. Further south, the oldest evidence for modern humans came from Bajondillo Cave on Spain’s southern coast.

“Bajondillo offered tantalising but controversial evidence that modern humans were in the area earlier than we thought,” says Haws. “The evidence in our report definitively supports the Bajondillo implications for an early modern human arrival.”

How they got there is still unclear, he adds. It’s likely they followed east-west flowing rivers, but they could also have migrated along the coast.

A nearby cave contains evidence of Neanderthal survival until 37,000 years ago. As yet there’s no evidence of interaction with modern humans. The tools used by our ancestors, featuring flint and small blades probably used for hunting with arrows, differ markedly to the stone-tool technology used by Neanderthals.

Harsh cold, dry conditions evidenced by paleoclimatic cave sediments would have been challenging to contend with, says co-author Michael Benedetti from Portugal’s Universidade do Algarve, possibly disrupting Neanderthal habitats and opening them up for modern humans.

The discovery certainly opens a goldmine of material for further exploration – and after 25 years of excavating, they have yet to reach the bottom.

“We’re still digging,” says Haws, “and hope to find even more surprises.”

COSMOS

Natalie Parletta is a freelance science writer based in Adelaide and an adjunct senior research fellow with the University of South Australia.

Modern humans reached westernmost Europe 5,000 years earlier than previously known

Discovery may indicate that modern humans and Neanderthals lived in the area concurrently

View of excavation of Lapa do Picareiro, looking in from the cave's entrance.

September 29, 2020

Modern humans arrived in westernmost Europe 38,000 - 41,000 years ago, about 5,000 years earlier than previously known, according to Jonathan Haws of the University of Louisville and an international team of researchers. In a report published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team reveals the discovery of stone tools used by modern humans that indicate the earlier arrival.

The tools, discovered in a cave near the Atlantic coast of central Portugal, link the site with similar finds from across Eurasia to the Russian plain and indicate a rapid westward dispersal of modern humans across Eurasia within a few thousand years of their first appearance in southeastern Europe. The tools provide evidence of the presence of modern humans in westernmost Europe at a time when Neanderthals were thought to be present in the region. The discovery has important ramifications for understanding the possible interaction between the two human groups and the ultimate disappearance of the Neanderthals.

"The question whether the last surviving Neanderthals in Europe have been replaced or assimilated by incoming modern humans is a long-standing, unsolved issue in paleoanthropology," said project co-leader Lukas Friedl. Freidl said that the early dating of stone tools associated with modern humans would "likely rule out the possibility that modern humans arrived into the land long devoid of Neanderthals, and that by itself is exciting."

Until now, the oldest evidence for modern humans south of the Ebro River in Spain came from Bajondillo, a cave site on the southern coast.

"The spread of anatomically modern humans across Europe many thousands of years ago is central to our understanding of where we came from as a now-global species," said John Yellen, program director for archaeology and archaeometry at the U.S. National Science Foundation, which supported the work through multiple research awards. "This discovery offers significant new evidence that will help shape future research investigating when and where anatomically modern humans arrived in Europe and what interactions they may have had with Neanderthals."

The cave sediments also contain a well-preserved paleoclimatic record that helps reconstruct environmental conditions at the time of the last Neanderthals and arrival of modern humans.

Said Michael Benedetti of the University of North Carolina Wilmington, "Our analysis shows that the arrival of modern humans corresponds with, or slightly predates, a bitterly cold and extremely dry phase. Harsh environmental conditions during this period posed challenges that both modern human and Neanderthal populations had to contend with."

The cave itself has an enormous amount of sediment remaining for future work, and the excavation still hasn't reached the bottom.

"I've been excavating at Picareiro for 25 years and, just when you start to think it might be done giving up its secrets, a new surprise gets unearthed," Haws said. "Every few years something remarkable turns up, and we keep digging."

-- NSF Public Affairs, researchnews@nsf.gov

No comments:

Post a Comment