Lighter nights, orange sunsets, straying killer whales: Wayne Davidson has observed the subtle signs of a tragically warming Arctic for four decades

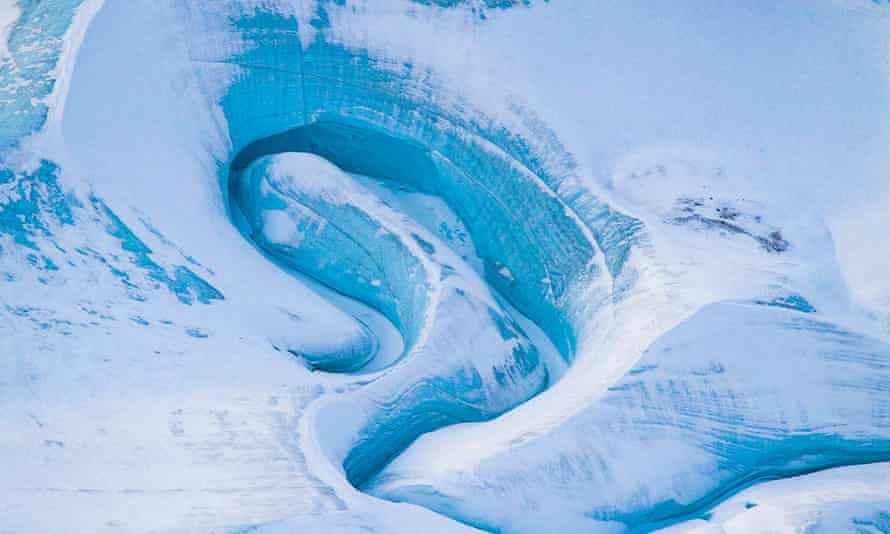

Melting channels in an ice shelf on Ellesmere Island, Nunavut. Photograph: Nasa/Jeremy Harbeck/Handout/EPA

Edward Helmore

Sat 14 Aug 2021

Wayne Davidson has been taking atmospheric readings from the Arctic Weather Station at Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island, Nunavut, for 40 years.

The climate of the high Arctic, he believes, is a guide in many respects to our past and is also the place from which our climate future can be previewed, as this week’s IPCC climate change report laid out in stark terms.

Davidson’s job in Nunavut is to observe and record temperature, pressure, wind and humidity through the atmosphere via twice-daily readings from weather balloons. Sunsets and sunrises, ice formation and the movement of animals are in a sense secondary, but in the Arctic environment also critical to understand the changes taking place.

“With respect to climate science, I’m at the frontier of observation,” Davidson told the Guardian.

Never has that job been so important. The IPCC report declared the climate crisis causing havoc around the globe is unequivocally caused by human activities and is battering every corner of the planet. Produced by hundreds of the world’s top scientists and signed off by the world’s governments, it concludes things could get far worse if the small chance remaining to avert heating above 1.5C is not taken.

When Davidson first took his position, relocating for nine months of the year from Montreal, it was in a sense an ordinary job making sea ice observations and so on. The Arctic, he says was “a love at first sight” and the job “more fun than working in a high-rise tower studying the weather with satellite pictures”.

In 2005, Davidson, technically a meteorological observer, told a visiting reporter that the Arctic could experience “Florida summers in 20 years”. The prediction then seemed both sickening and far-fetched. Now it’s sickening still, but much less far-fetched.

Air temperatures in the Arctic have indeed touched at times Floridian equivalence. Headline events are equally shocking: tundra aflame, dramatic ice cap melts, loss of seasonal and year-round sea ice, walrus with no ice floes to calve and drowning polar bears. For Davidson, watching all thus unfold, the climate report came as little surprise.

“I have tried to assimilate myself to the atmosphere, into this invisible world, one that we don’t understand, without any distractions,” Davidson says. Enrapturing as it is, he adds, the Arctic remains a place we barely understand. “We are starting to understand it better, but by the time we do it will be gone. I am really not happy about it.”

Advertisement

In some ways, the changes that Davidson and Inuit hunters are witnessing are more unnerving than stock images of collapsing glaciers and hungry animals. Hunters say they have noticed for years that the dark Arctic night is becoming lighter, as a warmer layer of air over the Arctic acts as a conduit for light from the south. The light, too, is different, taking on shades of blue, green and red.

Sunsets in the high Arctic, Davidson says, were once pure white and prolonged viewing painful to the naked eye. That’s no longer the case. Sunsets are no longer white but orange or red, a function both of particulates but more importantly atmospheric temperature differentials caused by the loss of sea ice.

Edward Helmore

Sat 14 Aug 2021

Wayne Davidson has been taking atmospheric readings from the Arctic Weather Station at Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island, Nunavut, for 40 years.

The climate of the high Arctic, he believes, is a guide in many respects to our past and is also the place from which our climate future can be previewed, as this week’s IPCC climate change report laid out in stark terms.

Davidson’s job in Nunavut is to observe and record temperature, pressure, wind and humidity through the atmosphere via twice-daily readings from weather balloons. Sunsets and sunrises, ice formation and the movement of animals are in a sense secondary, but in the Arctic environment also critical to understand the changes taking place.

“With respect to climate science, I’m at the frontier of observation,” Davidson told the Guardian.

Never has that job been so important. The IPCC report declared the climate crisis causing havoc around the globe is unequivocally caused by human activities and is battering every corner of the planet. Produced by hundreds of the world’s top scientists and signed off by the world’s governments, it concludes things could get far worse if the small chance remaining to avert heating above 1.5C is not taken.

When Davidson first took his position, relocating for nine months of the year from Montreal, it was in a sense an ordinary job making sea ice observations and so on. The Arctic, he says was “a love at first sight” and the job “more fun than working in a high-rise tower studying the weather with satellite pictures”.

In 2005, Davidson, technically a meteorological observer, told a visiting reporter that the Arctic could experience “Florida summers in 20 years”. The prediction then seemed both sickening and far-fetched. Now it’s sickening still, but much less far-fetched.

Air temperatures in the Arctic have indeed touched at times Floridian equivalence. Headline events are equally shocking: tundra aflame, dramatic ice cap melts, loss of seasonal and year-round sea ice, walrus with no ice floes to calve and drowning polar bears. For Davidson, watching all thus unfold, the climate report came as little surprise.

“I have tried to assimilate myself to the atmosphere, into this invisible world, one that we don’t understand, without any distractions,” Davidson says. Enrapturing as it is, he adds, the Arctic remains a place we barely understand. “We are starting to understand it better, but by the time we do it will be gone. I am really not happy about it.”

Advertisement

In some ways, the changes that Davidson and Inuit hunters are witnessing are more unnerving than stock images of collapsing glaciers and hungry animals. Hunters say they have noticed for years that the dark Arctic night is becoming lighter, as a warmer layer of air over the Arctic acts as a conduit for light from the south. The light, too, is different, taking on shades of blue, green and red.

Sunsets in the high Arctic, Davidson says, were once pure white and prolonged viewing painful to the naked eye. That’s no longer the case. Sunsets are no longer white but orange or red, a function both of particulates but more importantly atmospheric temperature differentials caused by the loss of sea ice.

The sunset on 20 March 2009. Photograph: Wayne Davidson

Davidson says the Arctic has not quite reached the heat of a Florida summer, “but we’re getting there”. Sea ice, he says, is thin but is saved for now by clouds that form as a result of evaporation from contact between the ice and warming air. “They’re the only thing that’s preventing it from disappearing every summer,” he said.

For now 2012 holds the record for the lowest level of September minimum sea ice. Each year since, that record low is approached. Last winter, Davidson says, sea ice was “amazingly thin” in Resolute Bay. Warm air from Pacific cyclones is warming the region, even in darkness. Instead of temperatures of minus 40 for weeks on end, it’s minus 25.

“The winters used to be bitter cold and amazingly brutal, now they are brutal at times,” he said.

The life of an Arctic atmospheric scientist, living with and among the Inuit, comes with strange customs. Davidson carries a sword to work, an accessory to fend off wolverines and more so polar bears, though he has little faith in this line of protection. “I’ve been lucky,” he said. “I think I’d lose the fight.”

Relations between Inuit communities and the modern world are less intrusive and more cooperative, Davidson says. He points out that Erebus and Terror, the two British exploratory warships lost in 1848 under the command of John Franklin, would probably never have been found without local knowledge and cooperation.

“The core of that tragedy, of course, was the failure to understand the local people. Franklin regarded his culture as superior and that’s what killed him,” Davidson said.

But disputes endure.

Earlier this year, protests erupted in Pond Inlet over plans to expand the Mary River iron ore mine. Representatives for the Inuit community said an expansion would damage caribou, seal and narwhal. More than 1,000 miles east, in Greenland, the government aligned with mining interests lost national elections to the Inuit Ataqatigiit party, which opposed the expansion of rare earth mineral mining.

Davidson says the biggest natural-world story is the encroachment of killer whales that are coming up to hunt beluga and narwhal. This, too, may be a result of thin ice – the whales are usually averse to bumping their large dorsal fins. For now, their prey are relatively protected from being trapped in the inlets and fjords by pack ice clogging the channels.

If that ice disappears, the beluga and narwhal may find themselves more exposed. In all these things, Davidson says, the Arctic is now a transitional, not permanent, world. “It’s an illusion of sorts. The pack ice is either going to go on or go out completely. But there’s no chance it’s going back to cold. Everything is warming.”

Of course, this is not something that affects the far north alone. Less temperature contrast between the tropics and Arctic creates a weaker and less persistent jet stream, which creates stagnant weather systems. Consequently, heatwaves and rains become more intense; floods and fires are the result – as we have seen this summer from Oregon to Greece to Germany to Russia.

These outcomes, Davidson says, are nothing short of tragedy, as the rest of the world catches up with what northerners have been feeling for years.

“We were used to a certain climate world and now we’re going to have to get used to something else. The world down south is trying to manage its own disasters, while the world in the north has been getting the rough end of it.”

The two may now be converging.

Davidson says the Arctic has not quite reached the heat of a Florida summer, “but we’re getting there”. Sea ice, he says, is thin but is saved for now by clouds that form as a result of evaporation from contact between the ice and warming air. “They’re the only thing that’s preventing it from disappearing every summer,” he said.

For now 2012 holds the record for the lowest level of September minimum sea ice. Each year since, that record low is approached. Last winter, Davidson says, sea ice was “amazingly thin” in Resolute Bay. Warm air from Pacific cyclones is warming the region, even in darkness. Instead of temperatures of minus 40 for weeks on end, it’s minus 25.

“The winters used to be bitter cold and amazingly brutal, now they are brutal at times,” he said.

The life of an Arctic atmospheric scientist, living with and among the Inuit, comes with strange customs. Davidson carries a sword to work, an accessory to fend off wolverines and more so polar bears, though he has little faith in this line of protection. “I’ve been lucky,” he said. “I think I’d lose the fight.”

Relations between Inuit communities and the modern world are less intrusive and more cooperative, Davidson says. He points out that Erebus and Terror, the two British exploratory warships lost in 1848 under the command of John Franklin, would probably never have been found without local knowledge and cooperation.

“The core of that tragedy, of course, was the failure to understand the local people. Franklin regarded his culture as superior and that’s what killed him,” Davidson said.

But disputes endure.

Earlier this year, protests erupted in Pond Inlet over plans to expand the Mary River iron ore mine. Representatives for the Inuit community said an expansion would damage caribou, seal and narwhal. More than 1,000 miles east, in Greenland, the government aligned with mining interests lost national elections to the Inuit Ataqatigiit party, which opposed the expansion of rare earth mineral mining.

Davidson says the biggest natural-world story is the encroachment of killer whales that are coming up to hunt beluga and narwhal. This, too, may be a result of thin ice – the whales are usually averse to bumping their large dorsal fins. For now, their prey are relatively protected from being trapped in the inlets and fjords by pack ice clogging the channels.

If that ice disappears, the beluga and narwhal may find themselves more exposed. In all these things, Davidson says, the Arctic is now a transitional, not permanent, world. “It’s an illusion of sorts. The pack ice is either going to go on or go out completely. But there’s no chance it’s going back to cold. Everything is warming.”

Of course, this is not something that affects the far north alone. Less temperature contrast between the tropics and Arctic creates a weaker and less persistent jet stream, which creates stagnant weather systems. Consequently, heatwaves and rains become more intense; floods and fires are the result – as we have seen this summer from Oregon to Greece to Germany to Russia.

These outcomes, Davidson says, are nothing short of tragedy, as the rest of the world catches up with what northerners have been feeling for years.

“We were used to a certain climate world and now we’re going to have to get used to something else. The world down south is trying to manage its own disasters, while the world in the north has been getting the rough end of it.”

The two may now be converging.

No comments:

Post a Comment