(Rod Long/Unsplash)

CLARE WATSON

1 JANUARY 2022

Our planet's convoluted history of evolving life has spawned countless weird and wonderful creatures, but none excite evolutionary biologists – or divide taxonomists – quite like crabs.

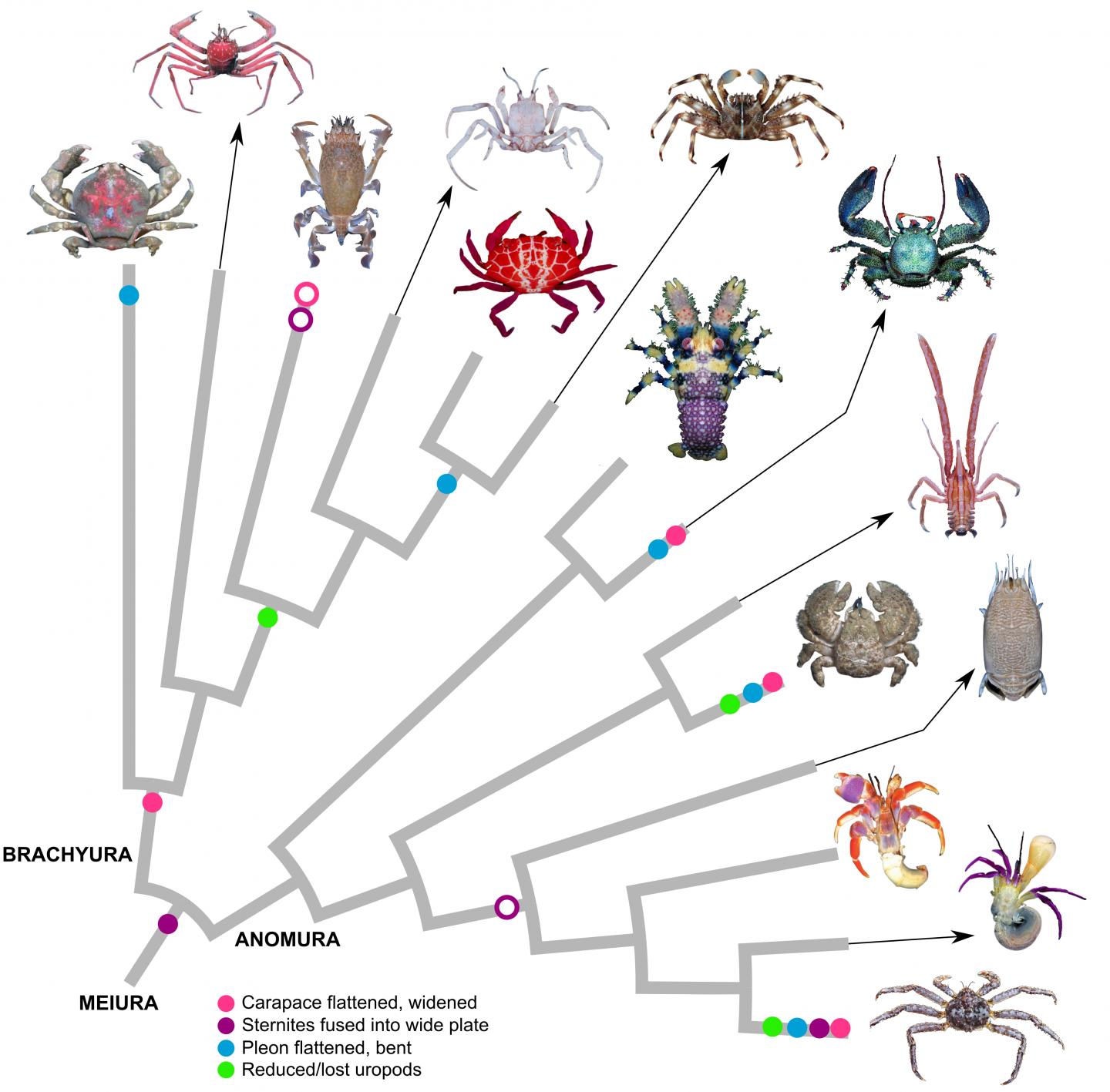

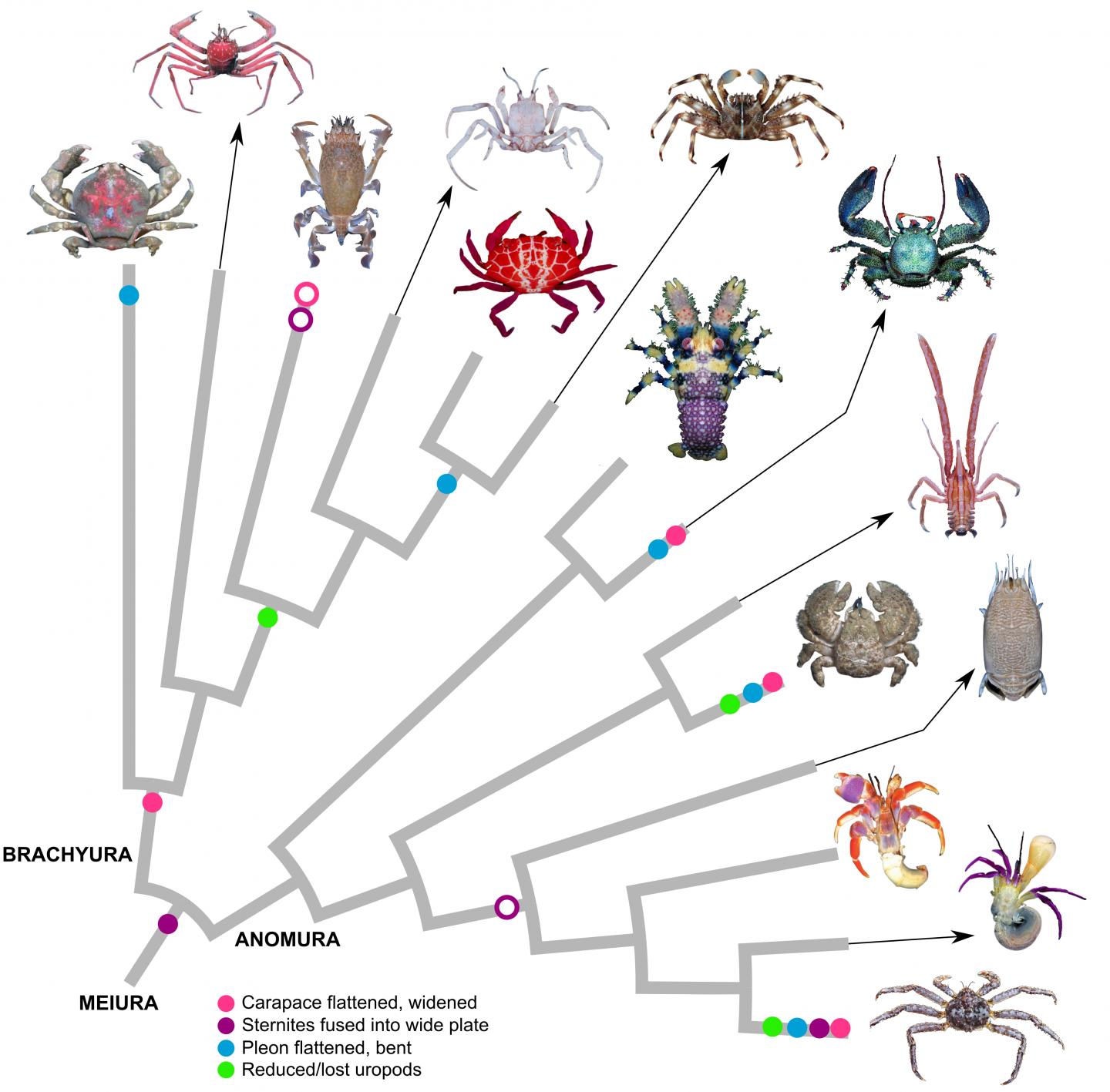

When researchers attempted to reconcile the evolutionary history of crabs in all their raucous glory just earlier this year, they arrived at the conclusion that the defining features of crabbiness have evolved at least five times in the past 250 million years.

What's more, crabbiness has been lost possibly seven times or more.

This repeated evolution of a crab-like body plan has happened so often it has its own name: carcinization. (And yes, if you lose crabbiness to evolution, it's called decarcinization.)

Frog crabs (Raninidae) are one unusual example. Features of the crab body plan were also lost en route to almost-legless Puerto Rican sand crabs (Emerita portoricensis) and various lop-sided hermit crabs – but then red king crabs regained crabby features at the last evolutionary minute.

A Puerto Rican sand crab.

(Michelle Barros Sarmento Gama/iNaturalist/CC BY-NC 4.0)

Why evolution keeps crafting and shafting the crab-like body plan remain but a mystery, though evolution must be doing something right in fashioning crabby creatures time and time again.

There are thousands of crab species, which thrive in almost every habitat on Earth, from coral reefs and abyssal plains to creeks, caves and forests.

Crabs also boast an impressive display of sizes. The smallest, the pea crab (Pinnothera faba), measures just millimeters, while the largest, the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi), spans nearly 4 meters (around 12 feet) from claw to claw.

With their species richness, extravagant array of body shapes and rich fossil record, crabs are an ideal group to study trends in biodiversity through time. But finding some order in the chaos of crabs is an ongoing challenge.

What's a crab, anyway?

It gets weirder, because not every crab is a crab, so to speak. There are 'true' crabs, such as mud crabs and swimmer crabs. Yet we also have so-called false crabs, such as shell-shy hermit crabs with their spiraling abdomens, or the spike-covered king crabs.

The most visible difference between true and false crabs is how many walking legs they have: true crabs have four pairs of lanky legs, whereas false crabs only have three, with another pint-sized pair at the rear.

Both true and false crabs evolved their wide, flat, hard upper shell and tucked tails independently of one another, from a common ancestor that had none of those features, suggests an analysis published in March 2021, led by evolutionary biologist Joanna Wolfe of Harvard University.

But it wasn't a straightforward path after true and false crabs split. Evolution has made and remade crabs over the past 250 million years: once or twice in true crabs and at least three times during the evolution of false crabs, Wolfe and colleagues think.

Crabs have long stumped taxonomists who have invariably misclassified species as true or false crabs due to their striking similarities.

Besides figuring out where species belong in the tree of life, understanding exactly how many times evolution has crafted the crab-like body form and why, could reveal something about what drives convergent evolution.

"There has to be some kind of evolutionary advantage to be this crablike shape," crab expert and Wolfe's co-author Heather Bracken-Grissom told Popular Science in 2020, when carcinization had sent the internet into a spin.

As with many subjects, evolutionary biologists have plenty of ideas, but no firm answers on carcinization. Due to the narrow focus of past research on select crab species, "the unparsimonious history of crab body plan evolution must be reconciled", the team writes.

To make a start, the trio of researchers compiled data on crab morphology, behavior and natural history, from living species and fossils, and identified the gaps in genetic data which might help to resolve puzzling evolutionary relationships.

"Almost half of the branches on the crab tree of life remain dark," they write.

Most carcinized crabs have developed hard, calcified shells to protect themselves from predators – a clear advantage – but then some crabs have abandoned this protection, for reasons unknown.

Walking sideways, silly as it seems, means crabs are supremely agile, able to make a speedy exit in either direction without losing sight of a predator, should one appear. But sideways walking is not observed in all carcinized lineages (there are forward-walking spider crabs) and some uncarcinzed hermit crabs can walk sideways, too.

That some crabs evolved outsized claws to become shell-crushing predators in an ecological arms race also cannot fully explain the timing or successes of early crab evolution.

Why evolution keeps crafting and shafting the crab-like body plan remain but a mystery, though evolution must be doing something right in fashioning crabby creatures time and time again.

There are thousands of crab species, which thrive in almost every habitat on Earth, from coral reefs and abyssal plains to creeks, caves and forests.

Crabs also boast an impressive display of sizes. The smallest, the pea crab (Pinnothera faba), measures just millimeters, while the largest, the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi), spans nearly 4 meters (around 12 feet) from claw to claw.

With their species richness, extravagant array of body shapes and rich fossil record, crabs are an ideal group to study trends in biodiversity through time. But finding some order in the chaos of crabs is an ongoing challenge.

What's a crab, anyway?

It gets weirder, because not every crab is a crab, so to speak. There are 'true' crabs, such as mud crabs and swimmer crabs. Yet we also have so-called false crabs, such as shell-shy hermit crabs with their spiraling abdomens, or the spike-covered king crabs.

The most visible difference between true and false crabs is how many walking legs they have: true crabs have four pairs of lanky legs, whereas false crabs only have three, with another pint-sized pair at the rear.

Both true and false crabs evolved their wide, flat, hard upper shell and tucked tails independently of one another, from a common ancestor that had none of those features, suggests an analysis published in March 2021, led by evolutionary biologist Joanna Wolfe of Harvard University.

But it wasn't a straightforward path after true and false crabs split. Evolution has made and remade crabs over the past 250 million years: once or twice in true crabs and at least three times during the evolution of false crabs, Wolfe and colleagues think.

Crabs have long stumped taxonomists who have invariably misclassified species as true or false crabs due to their striking similarities.

Besides figuring out where species belong in the tree of life, understanding exactly how many times evolution has crafted the crab-like body form and why, could reveal something about what drives convergent evolution.

"There has to be some kind of evolutionary advantage to be this crablike shape," crab expert and Wolfe's co-author Heather Bracken-Grissom told Popular Science in 2020, when carcinization had sent the internet into a spin.

To make a start, the trio of researchers compiled data on crab morphology, behavior and natural history, from living species and fossils, and identified the gaps in genetic data which might help to resolve puzzling evolutionary relationships.

"Almost half of the branches on the crab tree of life remain dark," they write.

Most carcinized crabs have developed hard, calcified shells to protect themselves from predators – a clear advantage – but then some crabs have abandoned this protection, for reasons unknown.

Walking sideways, silly as it seems, means crabs are supremely agile, able to make a speedy exit in either direction without losing sight of a predator, should one appear. But sideways walking is not observed in all carcinized lineages (there are forward-walking spider crabs) and some uncarcinzed hermit crabs can walk sideways, too.

That some crabs evolved outsized claws to become shell-crushing predators in an ecological arms race also cannot fully explain the timing or successes of early crab evolution.

(Joanna M. Wolfe)

Above: Phylogenetic tree showing examples of carcinized and decarcinized clades, with colored dots noting characteristics on the branches.

Like anything in science, nothing is ever settled and evolution will continue on its merry way. Though with increasing amounts of genomic information on living and fossilized crab species, rest assured taxonomists are steadily piecing together what makes a crab, a crab.

This "will allow us to resolve the multiple origins and losses of 'crab' body forms through time and identify the timing of origin of key evolutionary novelties and body plans," says Wolfe.

More than that, studying crabs provides a tantalizing prospect for evolutionary sleuths who think it might be possible to anticipate the predictable shapes evolution makes based on environmental factors and genetic cues.

"Examining crab evolution provides a macroevolutionary timescale of 250 million years ago for which, with enough phylogenetic and genomic data, we might be able to predict the morphology that would result," says Bracken-Grissom.

A crab-like shape might be a safe bet.

The paper was published in BioEssays.

Above: Phylogenetic tree showing examples of carcinized and decarcinized clades, with colored dots noting characteristics on the branches.

Like anything in science, nothing is ever settled and evolution will continue on its merry way. Though with increasing amounts of genomic information on living and fossilized crab species, rest assured taxonomists are steadily piecing together what makes a crab, a crab.

This "will allow us to resolve the multiple origins and losses of 'crab' body forms through time and identify the timing of origin of key evolutionary novelties and body plans," says Wolfe.

More than that, studying crabs provides a tantalizing prospect for evolutionary sleuths who think it might be possible to anticipate the predictable shapes evolution makes based on environmental factors and genetic cues.

"Examining crab evolution provides a macroevolutionary timescale of 250 million years ago for which, with enough phylogenetic and genomic data, we might be able to predict the morphology that would result," says Bracken-Grissom.

A crab-like shape might be a safe bet.

The paper was published in BioEssays.

No comments:

Post a Comment