Those responsible for the opioid-related deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans are yet to be held accountable.

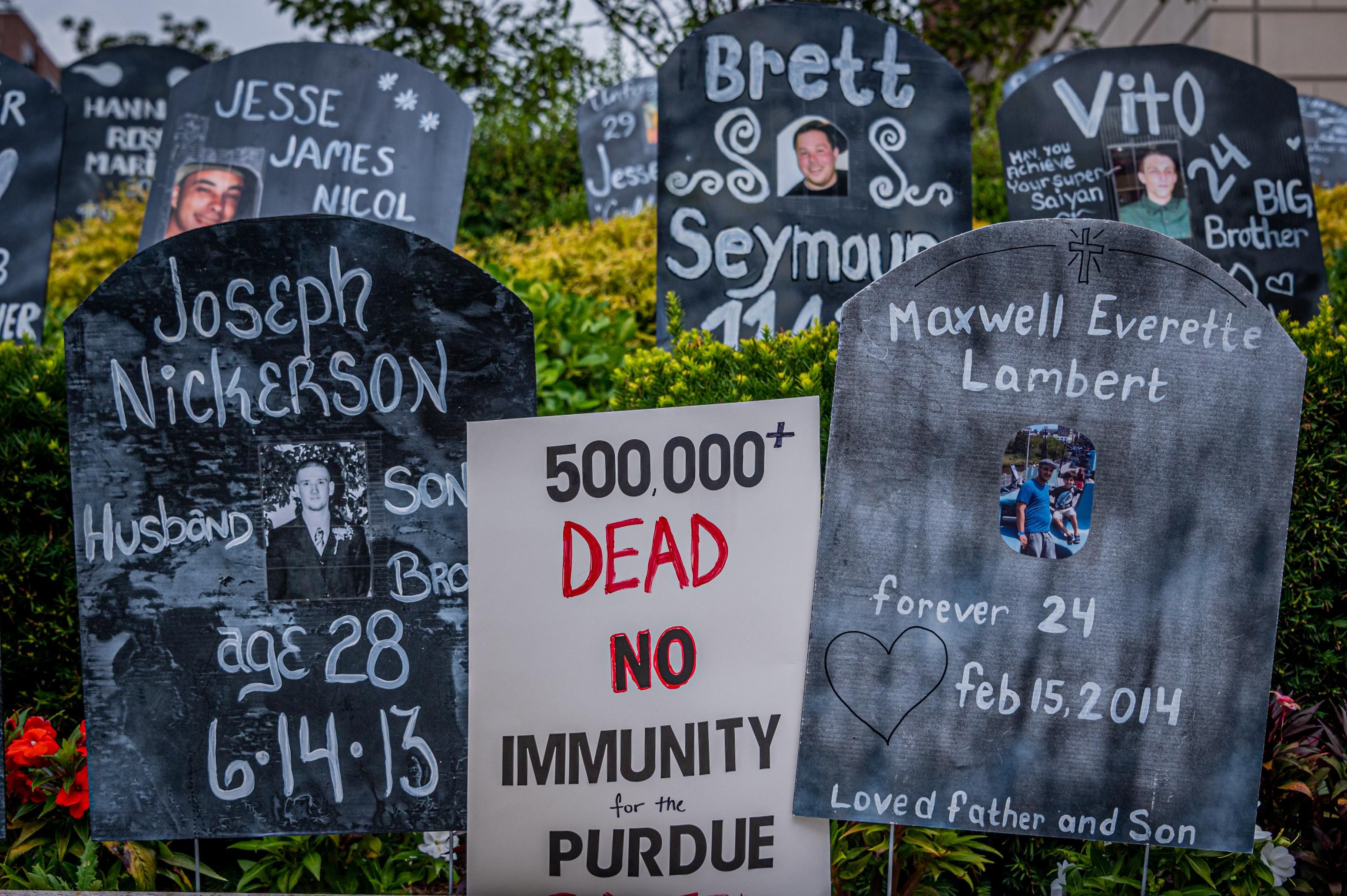

Tombstones honoring the victims of the overdose crisis seen planted outside the courthouse. Members of P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), Truth Pharm, and a coalition of survivors and advocacy groups working in response to the overdose crisis held a demonstration outside of The United States Bankruptcy Court in White Plains to call out the United States justice system for allowing the billionaire Sackler Family to walk away unscathed after igniting one of the worst public health care scandals in the history of the nation. (Photo: Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images)

BELÉN FERNÁNDEZ

January 3, 2022

by Al-Jazeera English

The other day in Mexico, I fell into conversation with an older gentleman from Virginia who had recently lost a brother to cancer. Choking up as he recalled how, as a child, his brother would approach parents on the street to compliment them on the beauty of their offspring, the gentleman added that cancer had not been his brother's only affliction. He had also, he said, been a victim of "the other epidemic"—meaning the opioid crisis that caused some 500,000 overdose deaths in the United States between 1999 and 2019, while destroying countless more lives through addiction.

The company's deflection of culpability onto the very victims of its predatory business model is furthermore symptomatic of a domestic neoliberal landscape in which poor individuals are blamed for their failure to succeed in the society that is effectively killing them.

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated the overdose phenomenon, with deaths in the US now surpassing 100,000 per year. Approximately 75 percent of these are attributed to opioids—a class of drugs that includes heroin, synthetic fentanyl, and prescription painkillers like oxycodone.

A December op-ed in the New York Times, titled "Opioids Feel Like Love. That's Why They're Deadly in Tough Times", explains that such drugs "mimic the neurotransmitters that are responsible for making social connection comforting—tying parent to child, lover to beloved".

The article emphasises that isolation and loneliness often fuel addiction, and that a quadrupling of overdose death rates in the US over the past several decades has occurred in tandem with an increase in social isolation. A 2018 survey, for example, "found that only about half of participants felt that they had someone to turn to all or most of the time."

It is hardly surprising, then, that coronavirus stay-at-home protocols and social distancing measures would prompt many Americans to seek substitutes for human contact and affection—not that US society was ever very, um, loving.

To be sure, life can get pretty lonely in a country that prefers to spend trillions on war rather than ensuring that its citizens have adequate access to basic rights like healthcare—and where a depraved capitalist system actively thwarts inter-human solidarity in the interest of maintaining a tyranny of the elite.

Speaking of war, the figure of half a million—the number of Americans killed by opioid overdoses over two decades—happens to be the same as the number of Iraqi children reportedly killed by US sanctions alone as of 1996. When confronted with this statistic at the time, then-US Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright affirmed that "we think the price is worth it", which pretty much perfectly encapsulates capitalism's lethal logic.

So, too, does the case of Purdue Pharma—manufacturer of the massively addictive prescription painkiller OxyContin—owned by the billionaire Sackler family. As was noted in a December 2020 U.S. congressional hearing on the role of Purdue and the Sacklers in the opioid epidemic, "Purdue targeted high-volume prescribers to boost sales of OxyContin, ignored and worked around safeguards intended to reduce prescription opioid misuse, and promoted false narratives about their products to steer patients away from safer alternatives and deflect blame toward people struggling with addiction."

Indeed, former Purdue executive Richard Sackler once stated in an email that "abusers" of OxyContin (a brand of oxycodone) were "the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals"—a charming assessment, no doubt, from the person overseeing the reckless flooding of US communities with dangerously addictive substances.

Purdue Pharma was dissolved in 2021 in a settlement that will render the Sacklers slightly lesser billionaires, a predictable form of "justice" in a country where poor people of colour are regularly sentenced to life in prison or forced to endure other, similarly life-shattering punishments for minor drug-related offences. The scene becomes all the more sickening when one considers that persons addicted to OxyContin often turn to heavily criminalised drugs like heroin when the so-called "legal" ones are not available.

During the aforementioned US congressional hearing, one state representative offered his straightforward opinion to David Sackler, a former member of the board of directors of Purdue Pharma: "I'm not sure that I'm aware of any family in America that's more evil than yours".

But while the Sacklers have been singled out for allegedly uniquely nefarious machinations, Purdue Pharma was merely part and parcel of the American way: making a killing from killing. Just ask the arms industry.

The company's deflection of culpability onto the very victims of its predatory business model is furthermore symptomatic of a domestic neoliberal landscape in which poor individuals are blamed for their failure to succeed in the society that is effectively killing them—and making them foot the bill for the honour.

Other US corporate actors have also faced litigation for their contributions to the opioid epidemic. In November, a federal jury in Ohio found that CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart—three of the country's most prominent pharmacy chains—had been complicit in creating a "public nuisance." And yet this is still a rather banal indictment in a criminally carceral nation where government-corporate collusion in a profitable and lethal addiction to capitalism has produced a system that is thoroughly sick.

And as long as opioids "feel like love" in an otherwise loveless panorama, there is no end in sight to the crisis.

The other day in Mexico, I fell into conversation with an older gentleman from Virginia who had recently lost a brother to cancer. Choking up as he recalled how, as a child, his brother would approach parents on the street to compliment them on the beauty of their offspring, the gentleman added that cancer had not been his brother's only affliction. He had also, he said, been a victim of "the other epidemic"—meaning the opioid crisis that caused some 500,000 overdose deaths in the United States between 1999 and 2019, while destroying countless more lives through addiction.

The company's deflection of culpability onto the very victims of its predatory business model is furthermore symptomatic of a domestic neoliberal landscape in which poor individuals are blamed for their failure to succeed in the society that is effectively killing them.

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated the overdose phenomenon, with deaths in the US now surpassing 100,000 per year. Approximately 75 percent of these are attributed to opioids—a class of drugs that includes heroin, synthetic fentanyl, and prescription painkillers like oxycodone.

A December op-ed in the New York Times, titled "Opioids Feel Like Love. That's Why They're Deadly in Tough Times", explains that such drugs "mimic the neurotransmitters that are responsible for making social connection comforting—tying parent to child, lover to beloved".

The article emphasises that isolation and loneliness often fuel addiction, and that a quadrupling of overdose death rates in the US over the past several decades has occurred in tandem with an increase in social isolation. A 2018 survey, for example, "found that only about half of participants felt that they had someone to turn to all or most of the time."

It is hardly surprising, then, that coronavirus stay-at-home protocols and social distancing measures would prompt many Americans to seek substitutes for human contact and affection—not that US society was ever very, um, loving.

To be sure, life can get pretty lonely in a country that prefers to spend trillions on war rather than ensuring that its citizens have adequate access to basic rights like healthcare—and where a depraved capitalist system actively thwarts inter-human solidarity in the interest of maintaining a tyranny of the elite.

Speaking of war, the figure of half a million—the number of Americans killed by opioid overdoses over two decades—happens to be the same as the number of Iraqi children reportedly killed by US sanctions alone as of 1996. When confronted with this statistic at the time, then-US Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright affirmed that "we think the price is worth it", which pretty much perfectly encapsulates capitalism's lethal logic.

So, too, does the case of Purdue Pharma—manufacturer of the massively addictive prescription painkiller OxyContin—owned by the billionaire Sackler family. As was noted in a December 2020 U.S. congressional hearing on the role of Purdue and the Sacklers in the opioid epidemic, "Purdue targeted high-volume prescribers to boost sales of OxyContin, ignored and worked around safeguards intended to reduce prescription opioid misuse, and promoted false narratives about their products to steer patients away from safer alternatives and deflect blame toward people struggling with addiction."

Indeed, former Purdue executive Richard Sackler once stated in an email that "abusers" of OxyContin (a brand of oxycodone) were "the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals"—a charming assessment, no doubt, from the person overseeing the reckless flooding of US communities with dangerously addictive substances.

Purdue Pharma was dissolved in 2021 in a settlement that will render the Sacklers slightly lesser billionaires, a predictable form of "justice" in a country where poor people of colour are regularly sentenced to life in prison or forced to endure other, similarly life-shattering punishments for minor drug-related offences. The scene becomes all the more sickening when one considers that persons addicted to OxyContin often turn to heavily criminalised drugs like heroin when the so-called "legal" ones are not available.

During the aforementioned US congressional hearing, one state representative offered his straightforward opinion to David Sackler, a former member of the board of directors of Purdue Pharma: "I'm not sure that I'm aware of any family in America that's more evil than yours".

But while the Sacklers have been singled out for allegedly uniquely nefarious machinations, Purdue Pharma was merely part and parcel of the American way: making a killing from killing. Just ask the arms industry.

The company's deflection of culpability onto the very victims of its predatory business model is furthermore symptomatic of a domestic neoliberal landscape in which poor individuals are blamed for their failure to succeed in the society that is effectively killing them—and making them foot the bill for the honour.

Other US corporate actors have also faced litigation for their contributions to the opioid epidemic. In November, a federal jury in Ohio found that CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart—three of the country's most prominent pharmacy chains—had been complicit in creating a "public nuisance." And yet this is still a rather banal indictment in a criminally carceral nation where government-corporate collusion in a profitable and lethal addiction to capitalism has produced a system that is thoroughly sick.

And as long as opioids "feel like love" in an otherwise loveless panorama, there is no end in sight to the crisis.

© 2021 Al-Jazeera English

BELÉN FERNÁNDEZ

Belén Fernández is the author of "Exile: Rejecting America and Finding the World" and "The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work." She is a member of the Jacobin Magazine editorial board, and her articles have appeared in the London Review of Books blog, Al Akhbar English and many other publications.

No comments:

Post a Comment