Gustavo Petro elected Colombia’s first left-wing president

BOGOTA, June 20 — Ex-guerrilla Gustavo Petro was elected the first ever left-wing president of crisis-wracked Colombia on Sunday after beating millionaire businessman Rodolfo Hernandez in a tense and unpredictable runoff election.

With more than 99.5 per cent of votes counted, Petro — the 62-year-old former mayor of Bogota — held an unassailable lead of more than three points with around 700,000 more votes than Hernandez, 77.

“Today is a celebration for the people. Let’s celebrate the first popular victory,” Petro wrote on Twitter.

Hernandez said he accepted the result in a Facebook live broadcast.

“I hope that Mr Gustavo Petro knows how to run the country and is faithful to his discourse against corruption,” said the construction magnate.

Petro will succeed the deeply unpopular conservative Ivan Duque, who was barred by Colombia’s constitution from standing for reelection, in a country saddled with widespread poverty, a surge in violence and other woes.

“May so much suffering be cushioned by the joy that today floods the heart of the Homeland. This victory is for God and for the People and their history. Today is the day of the streets and squares,” added Petro.

In another moment of history, environmental activist and feminist Francia Marquez, 40, will become Colombia’s first black woman vice-president.

Abstention was expected to be high among Colombia’s 39 million voters amid fears a tight result could spark post-election violence.

To ensure security, some 320,000 police and military have been deployed.

The electoral observer mission said one of Petro’s election monitors and a soldier were killed, both in the south.

Colombia is no stranger to political violence, with five presidential candidates having been murdered over the course of the 20th century.

Before the first round of this year’s presidential election, several candidates received death threats.

‘Dangerous’ accusations of fraud

When voting in Bogota, Petro, who comfortably topped last month’s first round, urged his supporters to turn out as rumours swirled on social media of election irregularities.

“Today, undoubtedly we must defeat any attempt at fraud with massive participation,” he said.

The national registrar, Alexander Vega, denounced such fears as “disinformation” while Hernandez, who voted in the northern city of Bucaramanga where he was mayor from 2016 to 2019, accused Petro of “creating an atmosphere of fraud.”

“It’s very dangerous for candidates to play with this idea (of fraud), it could easily erupt into post-election unrest,” Elizabeth Dickinson, Colombia analyst at the International Crisis Group in Bogota, told AFP.

With the traditional political powers suffering a chastening first round defeat, a lot of early voters seemed undecided, not just about who to vote for but what the candidates represented.

Petro has been in politics for 30 years, while Hernandez is an unconventional outsider with little experience.

Valentina Rios, 19, who voted in Bogota said whoever won “at least it will be a change.”

“For me, neither of them represents change,” countered Alejandro Bueno, 20, an economics student in the capital, who hoped for “a peaceful transition to the next government.”

Petro will have to deal with a country reeling economically from the coronavirus pandemic, a spike in drug-trafficking related violence and deep-rooted anger at the political establishment that spilled over into mass anti-government protests in April 2021.

Almost 40 per cent of the country lives in poverty while 11 per cent are unemployed.

Left-wing ideology is intrinsically linked in many Colombians’ minds to the country’s six-decade long multi-faceted conflict, leaving many to fear what a Petro presidency would represent.

Petro was a radical leftist urban guerrilla in the 1980s and spent almost two years in jail.

But his M-19 group made peace with the state in 1990 and formed a political party.

Impact of Venezuela ‘tragedy’

“The worry comes from the experience of leftist governments in the region,” Patricia Munoz, an expert at Pontifical Javerian University, told AFP.

Michael Shifter, from the Inter-American Dialogue think tank, said fears Colombia could turn into another authoritarian populist socialist state like neighbouring Venezuela “borders on hysteria.”

However, he said it’s understandable since Colombia has been affected more than any other Latin American country by “the Venezuela tragedy and nightmare.”

Until a few months ago, Hernandez was a virtual unknown outside of Bucaramanga.

He made the fight against corruption his main campaign pledge, although he is himself under investigation for graft.

He had vowed to “reduce the size of the state, end corruption and replace inept officials.”

But his other policies were unconventional and he lacked a clear program. — AFP

By Julie Turkewitz

For the first time in Colombia’s history, a Black woman is close to the top of the executive branch.

Francia Márquez, an environmental activist from the mountainous department of Cauca in southwestern Colombia, has become a national phenomenon, mobilizing decades of voter frustration, and becoming the country’s first Black vice president on Sunday, as the running mate to Gustavo Petro.

The Petro-Márquez ticket won Sunday’s runoff election, according to preliminary results. Mr. Petro, a former rebel and longtime legislator, will become the country’s first leftist president.

The rise of Ms. Márquez is significant not only because she is Black in a nation where Afro-Colombians are regularly subject to racism and must contend with structural barriers, but because she comes from poverty in a country where economic class so often defines a person’s place in society. Most recent former presidents were educated abroad and are connected to the country’s powerful families and kingmakers.

Despite economic gains in recent decades, Colombia remains starkly unequal, a trend that has worsened during the pandemic, with Black, Indigenous and rural communities falling the farthest behind. Forty percent of the country lives in poverty.

Ms. Márquez, 40, chose to run for office, she said, “because our governments have turned their backs on the people, and on justice and on peace.”

She grew up sleeping on a dirt floor in a region battered by violence related to the country’s long internal conflict. She became pregnant at 16, went to work in the local gold mines to support her child, and eventually sought work as a live-in maid.

To a segment of Colombians who are clamoring for change and for more diverse representation, Ms. Márquez is their champion. The question is whether the rest of the country is ready for her.

Some critics have called her divisive, saying she is part of a leftist coalition that seeks to tear apart, instead of build upon, past norms.

She has also never held political office, and Sergio Guzmán, director of Colombia Risk Analysis, a consulting firm, said that “there are a lot of questions as to whether Francia would be able to be commander in chief, if she would manage economic policy, or foreign policy, in a way that would provide continuity to the country.”

Her more extreme opponents have taken direct aim at her with racist tropes, and criticize her class and political legitimacy.

But on the campaign trail, Ms. Márquez’s persistent, frank and biting analysis of the social disparities in Colombia cracked open a discussion about race and class in a manner rarely heard in the country’s most public and powerful political circles.

Those themes, “many in our society deny them, or treat them as minor,” said Santiago Arboleda, a professor of Afro-Andean history at Simón Bolívar Andean University. “Today, they’re on the front page.”

Teen Mother. Housekeeper. Activist. Vice President?

Julie Turkewitz is the Andes bureau chief, covering Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, Suriname and Guyana. Before moving to South America, she was a national correspondent covering the American West. @julieturkewitz

Colombian presidential candidate Gustavo Petro, left, listens at a news conference in Bogotá, Colombia on May 31

Colombian presidential candidate Gustavo Petro, left, listens at a news conference in Bogotá, Colombia on May 31By Reuters

BOGOTA/BUCARAMANGA, Colombia — Leftist Gustavo Petro, a former member of the M-19 guerrilla movement who has vowed profound social and economic change, won Colombia’s presidency on Sunday, the first progressive to do so in the country’s history.

Petro beat construction magnate Rodolfo Hernandez with an unexpectedly wide margin of some 716,890 votes. The two had been technically tied in polling ahead of the vote.

Petro, a former mayor of capital Bogota and current senator, has pledged to fight inequality with free university education, pension reforms and high taxes on unproductive land. He won 50.5% to Hernandez’s 47.3%.

Petro’s proposals — especially a ban on new oil projects — have startled some investors, though he has promised to respect current contracts.

Supporter Alejandro Forero, 40, who uses a wheelchair, cried as results rolled in at the Petro campaign celebration in Bogota.

"Finally, thank God. I know he will be a good president and he will help those of us who are least privileged. This is going to change for the better,” said Forero, who is unemployed.

This campaign was Petro’s third presidential bid and his victory adds the Andean nation to a list of Latin American countries that have elected progressives in recent years.

Petro, 62, said he was tortured by the military when he was detained for his involvement with the guerrillas, and his potential victory has high-ranking armed forces officials bracing for change.

Petro’s running mate Francia Marquez, a single mother and former housekeeper, will be the country’s first Afro-Colombian woman vice-president.

“Today I’m voting for my daughter — she turned 15 two weeks ago and asked for just one gift: that I vote for Petro,” said security guard Pedro Vargas, 48, in Bogota’s southwest on Sunday morning

I hope this man fulfills the hopes of my daughter, she has a lot of faith in his promises,” added Vargas, who said he never votes.

Petro has also pledged to fully implement a 2016 peace deal with FARC rebels and seek talks with the still-active ELN guerrillas.

He had raised doubts about the integrity of the count after irregularities in congressional tallies in March, and earlier on Sunday urged voters to check their ballots for any extraneous marks which could invalidate them.

Hernandez, who served as mayor of Bucaramanga, was a surprise contender in the run-off and has promised to shrink government and to finance social programs by stopping corruption.

He has also pledged to provide free narcotics to addicts in an effort to combat drug trafficking.

Despite his anti-graft rhetoric, Hernandez is under a corruption investigation himself over allegations he intervened in a trash management tender to benefit a company his son lobbied for. He has denied wrongdoing.

Defense Minister Diego Molano told journalists on Sunday afternoon that the killing of an electoral volunteer in Guapi, Cauca province, was under investigation.

Sixty voting locations had to be moved because of heavy rains in some parts of the country, the registrar said.

Colombia elections: Ex-guerrilla leader

Gustavo Petro wins

Voters in Colombia decided between leftist Gustavo Petro and businessman Rodolfo Hernandez, whose sudden rise prompted comparisons with Donald Trump.

Businessman candidate Rodolfo Hernandez (left) is facing off against ex-guerrilla leader Gustavo Petro

Left-wing ex-guerrilla Gustavo Petro has achieved a narrow victory in Colombia's presidential election.

Polls opened for the second round of the Latin American nation's presidential election on Sunday, with former guerrilla leader Petro facing surprise rival Rodolfo Hernandez, a 77-year-old businessman who managed to build up a nationwide political following by relying on TikTok and Facebook.

The race between Petro and Hernandez was the tightest in the country in recent memory.

Gustavo Petro won Colombia's presidential election by over 700,000 votes

Hernandez conceded defeat in a video posted on social media.

"Colombians, today the majority of citizens have chosen the other candidate. As I said during the campaign, I accept the results of this election," Hernandez said.

Some 39 million people were eligible to vote in Colombia, a country where nearly 40% live below the poverty line and 11% are unemployed.

With the two anti-establishment candidates vying for the presidency, Sunday's ballot was seen as a powerful rebuke to the country's conservative elite and current president, Ivan Duque.

Petro wants to 'make history'

The 62-year-old Petro, a leftist with a reform agenda, comfortably won the initial vote last month by securing some 40.4% of the ballots. The result is a sensation on its own, as a large part of Colombia's population harbors deep distrust of both his policies and his past in the now-defunct M-19 urban rebel group, which included two years in prison on arms charges.

But his supporters point to Petro's plans to redistribute pensions, make public universities free and tackle the country's inequality and poverty. He has also said he will put a stop to new oil and gas projects.

"We're one step from achieving the real change we have waited for all our lives," Petro said. "We are going to make history."

Hernandez banks on TikTok

Perhaps more surprising was that Petro faced Hernandez on Sunday. The former mayor of the northern city of Bucaramanga, who presents himself as a political outsider, managed to win over 28% of the initial vote and edge out conservative candidate Federico Gutierrez for a chance to go against Petro in the second round.

Moreover, Hernandez had managed to close the gap between himself and Petro in the intervening weeks. The millionaire entrepreneur relied on TikTok and Facebook to reach potential voters. His wealth and unorthodox campaign strategy has prompted comparisons with former US President Donald Trump.

Hernandez has pledged to tackle corruption, despite facing an investigation for allegedly favoring his son's company in a waste management tender during his time as mayor of Bucaramanga. He has also promised to provide free narcotics to addicts in a bid to fight drug traffickers.

"The election is simple. Vote for someone who is controlled by the same people as always or vote for me, who isn't controlled by anyone," Hernandez said ahead of Sunday's vote.

But the electorate might take issue with videos that recently surfaced online showing the 77-year-old partying on a private yacht with several younger women. Others might be turned off by Hernandez's history of gaffes, most notably when he declared himself an admirer of "the great German thinker Adolf Hitler" in 2016. He later corrected himself by saying he was really talking about Albert Einstein.

Former guerrilla Gustavo Petro wins

Former fighter in the M-19 militia beat populist business

Joe Parkin Daniels

Colombia has elected a former guerrilla fighter Gustavo Petro as president, making him the South American country’s first leftist head of state.

Petro beat Rodolfo Hernández, a gaff-prone former mayor of Bucaramanga and business mogul, with 50.8% of the vote in a runoff election on Sunday and will take office in July amid a host of challenges, not least of which is the deepening discontent over inequality and rising costs of living. Hernández had 47.27%, with almost all ballots counted, according to results released by election authorities.

Petro’s election marks a tidal shift for Colombia, a country that has never before had a leftist president, and follows similar victories for the left in Peru, Chile and Honduras.

‘This is a revolution’: the faces of Colombia’s protests

“Today is a party for the people,” tweeted the victorious candidate on Sunday night after results came in. “May so many sufferings be cushioned in the joy that today floods the heart of the homeland.”

Petro’s journey from a fighter in the M-19 guerrilla army in the 80s to president also saw him become a senator and the mayor of the capital, Bogotá. He has a reputation for meandering speeches and high-handedness.

Petro’s vice-president will be Francia Márquez – a prize-winning defender of human and environmental rights – marking the first time that a black woman fills the post.

“Today all women win,” tweeted Márquez as polls closed on Sunday afternoon. “We are facing the greatest possibility of change in recent times.”

Hernández looked to be a contender, though could not escape an almost constant stream of scandal. He referred to Hitler as a “great German thinker” and has been filmed galavanting with models on a yacht in Miami. His posts on TikTok – from where he ran much of his campaign – were laden with profanity and he refused to attend any debates ahead of Sunday’s vote.

On the agenda for the new leader will be the country’s faltering peace process with the leftist rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), which was signed in 2016 and formally ended five decades of civil war that killed more than 260,000 people and displaced more than 7 million. The outgoing government of Iván Duque has been accused of slow-walking the accord’s implementation in order to undermine it.

Another headache for Petro will be neighbouring Venezuela, which has been mired in social, political and economic crisis for years. Petro has advocated for a reopening of ties with Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro, bucking the Duque government’s policy of isolation.

Petro has also pledged to wean the country off its dependence on fossil fuels, worrying investors.

The election was hotly contested, with many observers categorising the race between two relative outsiders as a wider rebuke against the political class. A host of traditional politicians were ousted in the first round.

Slim Win Makes Ex-rebel Colombia's First

Former rebel Gustavo Petro narrowly won a runoff election

REGINA GARCIA CANO and ASTRID SUAREZ

Jun 19, 2022

BOGOTA, Colombia (AP) — Former rebel Gustavo Petro narrowly won a runoff election over a political outsider millionaire Sunday, ushering in a new era of politics for Colombia by becoming the country’s first leftist president.

Petro, a senator in his third attempt to win the presidency, had 50.47% of the votes, while real estate magnate Rodolfo Hernández had 47.27%, with almost all ballots counted, according to results released by election authorities.

Petro will be officially declared winner after a formal count that will take a few days. Historically, the preliminary results have coincided with the final ones.

Petro’s victory underlined a drastic change in presidential politics for a country that has long marginalized the left for its perceived association with the armed conflict.

“Today is a day of celebration for the people. Let them celebrate the first popular victory,” Petro tweeted. “May so many sufferings be cushioned in the joy that today floods the heart of the Homeland.”

At his headquarters in the capital city of Bogota, a message on a screen read, “Gracias Colombia,” or “Thank you Colombia.”

Outgoing conservative President Iván Duque congratulated Petro shortly after results were announced, and Hernández quickly conceded his defeat.

“I accept the result, as it should be, if we want our institutions to be firm,” Hernández said in a video on social media. “I sincerely hope that this decision is beneficial for everyone.”

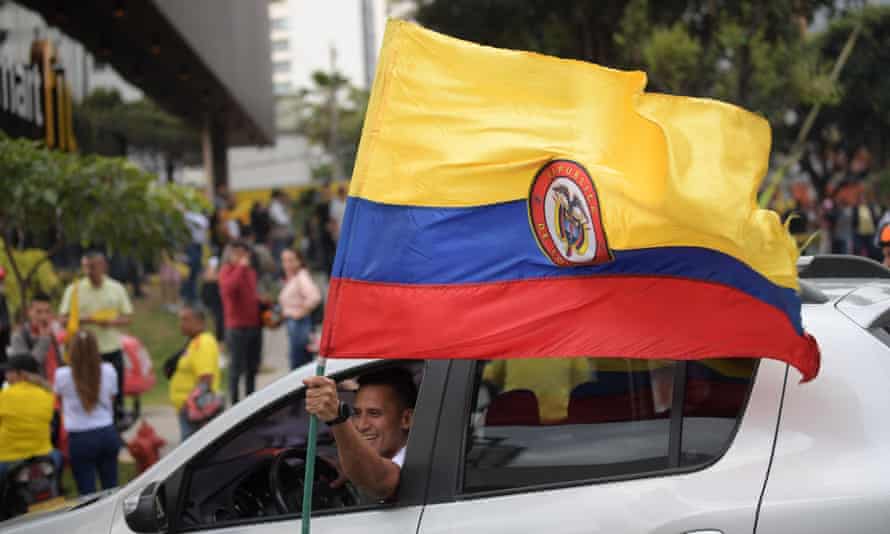

People watch a screen showing preliminary results of the presidential runoff election in Medellin, Colombia, on June 19, 2022. - Leftist ex-guerrilla Gustavo Petro took the lead over millionaire businessman rival Rodolfo Hernandez in early results of Colombia's presidential vote on Sunday, according to a live count on the Latin American country's election authority website. With 65 percent of votes counted, former mayor of Bogota Petro, 62, led by more than four points with nearly 600,000 more votes than maverick outsider Hernandez, 77.

About 39 million people were eligible to vote Sunday, but abstentionism has been above 40% in every presidential election since 1990.

The vote came amid widespread discontent over rising inequality, inflation and violence — factors that led voters in the first round to turn their backs on the long-governing centrist and right-leaning politicians and chose two outsiders in Latin America’s third-most populated nation.

Petro, 62, was once a rebel with the now-defunct M-19 movement and was granted amnesty after being jailed for his involvement with the group.

He has proposed ambitious pension, tax, health and agricultural reforms and changes to how Colombia fights drug cartels and other armed groups. He obtained 40% of the votes during last month’s election and Hernández 28%, but the difference quickly narrowed as Hernández began to attract so-called anti-Petrista voters.

Petro’s showing was the latest leftist political victory in Latin America fueled by voters’ desire for change. Chile, Peru and Honduras elected leftist presidents in 2021, and in Brazil, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is leading the polls for this year’s presidential election.

The 77-year-old Hernández, who made his money in real estate, is not affiliated with any major political party and rejected alliances. His austere campaign, waged mostly on TikTok and other social media platforms, was self-financed.

His proposals were based on a fight against corruption, which he blames for poverty and the loss of state resources that could be used on social programs. He wants to reduce the size of government by eliminating various embassies and presidential offices, turning the presidential palace into a museum and reducing the use of the president’s aircraft fleet.

Colombia Elections

VIA ASSOCIATED PRESS

Hernández surged late in the first-round campaign past more conventional candidates and shocked many when he finished second. He has faced controversies including saying he admired Adolf Hitler before apologizing and saying that he meant to refer to Albert Einstein.

Duque earlier Sunday urged Colombians to vote and trust the institutions “with full confidence in the verdict of the people.”

Petro had questioned election authorities during the campaign and said he would analyze after polls closed whether he accepts the results.

After casting his ballot, he called on supporters to vote in large numbers to “defeat any attempt at fraud” and claimed, without showing evidence, that voters in some polling stations were being given ballots previously marked as blank votes in an attempt to “cancel votes that would go for the change.”

Silvia Otero Bahamón, a political science professor at the University of Rosario, said that although both candidates are populists who “have an ideology based on the division between the corrupt elite and the people,” each sees their fight against the establishment differently.

“Petro relates to the poor, the ethnic and cultural minorities of the most peripheral regions of the nation,” Otero said, while Hernández’s supporters “are the people who have been let down by politicking and corruption. It is a looser community, which the candidate reaches directly via social networks.”

Polls say most Colombians believe the country is heading in the wrong direction and disapprove of Duque, who was not eligible to seek reelection. The pandemic set back the country’s anti-poverty efforts by at least a decade.

Official figures show that 39% of Colombia’s lived on less than $89 a month last year.

The rejection of politics as usual “is a reflection of the fact that the people are fed up with the same people as always,” said Nataly Amezquita, a 26-year-old civil engineer waiting to vote. “We have to create greater social change. Many people in the country aren’t in the best condition.”

But even the two outsider candidates left her cold. She said she would cast a blank ballot: “I don’t like either of the two candidates.... Neither of them seems like a good person to me.”

Many voters were basing their decision on what they do not want, instead of what they do want.

“Many people said, ‘I don’t care who is standing against Petro, I’m going to vote for whomever represents the other candidate, regardless of who that person is,’” said Silvana Amaya, a senior analyst with the firm Control Risks. “That also works the other way around. Rodolfo has been portrayed as this crazy old man, communication genius and extravagant character (so) that some people say: ‘I don’t care who I have to vote for, but I don’t want him to be my president.’”

Either will have a tough time delivering on promises as neither has a majority in Congress, which is key to carrying out reforms.

In recent legislative elections, Petro’s political movement obtained 20 seats in the Senate, a plurality, but he would still have to make concessions in negotiations with other parties. Hernández’s political movement only has two representatives in the lower house, so he would also have to seek agreements with lawmakers, whom he has alienated by repeatedly calling “thieves.”

Garcia Cano reported from Caracas, Venezuela.

Colombia’s First Leftist President Could Transform the Region

By Ivan Briscoe

Colombian President-elect Gustavo Petro in Bogotá, June 2022

In the lead-up to the country’s presidential election, members of Colombia’s high society braced for disaster. A habitué of the gentlemen’s clubs of Bogotá noted a tide of “catastrophe-minded hysteria” rolling through the salons. Businesses introduced special clauses permitting contracts to be struck down if the worst came to pass. Bleak mutterings circulated through the military barracks. The source of such widespread dread went by one name: Gustavo Petro, a former urban guerrilla, a socialist, and the leading contender in the race.

Those alarmed at the prospect of a Petro victory have had their fears confirmed. The 62-year-old Petro will be the country’s next leader, having defeated his opponent, Rodolfo Hernández—a 77-year-old real estate tycoon and relative political novice—in the runoff vote. This follows Hernández’s extraordinary upset victory in the first round of voting in late May, when he beat out Federico Gutiérrez, the center-right hopeful backed by the traditional parties, by espousing one message: “Colombia is captured by thieves.” But Hernández’s gambit finally failed him, and Colombia will soon be governed by its first leftist president.

In the sort of paradox that populist competition seems to invite, each campaign sought to present its candidate in the final weeks before the runoff as the sensible choice and the genuine political outsider. Hernández ultimately received the backing of much of Colombia’s political elite, which apparently chose to flay itself and run the risk of an authoritarian becoming president rather than let the left take power. But it was Petro, whose calls for change resonated with a public hungry for political, social, and economic transformation, who triumphed in this battle of antiestablishment credentials.

Petro’s win will have far-reaching implications in a region where Colombia has long been an anchor of relative political stability, despite the rising populist tide across Latin America. It is also telling regarding the current state of Colombian politics. Petro has promised to enact sweeping social changes, as well as measures such as halting new oil and gas exploration contracts and increasing taxes on the rich to pay for antipoverty programs and improved public services. Many of his proposed policies, including erecting so-called smart tariffs to protect Colombian agricultural production, could be poorly received in Washington.

To his supporters, Petro is a standard-bearer for Latin American progressivism who will usher in a new era of representation and egalitarianism. His critics, in contrast, accuse him of employing the same elite-baiting rhetoric that propelled to power other populist leaders, such as Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Peruvian President Pedro Castillo. And indeed, Petro’s record as a former mayor of Bogotá, his self-portrayal as an agent of historic transformation, and even some of his reported personality traits, such as his aversion to being contradicted, suggest to many that a demagogue may be lurking.

BATTLE OF THE OUTSIDERS

The significance of this electoral shock does not conform to any easily recognizable precedent. Petro’s triumph was by no means inevitable: in the weeks leading up to the runoff vote, the polls ranged wildly. Hernández’s plainspoken manner, social media following, and explosion onto the national political stage had seemed to give him an edge over his left-wing rival. In style, although perhaps not in substance, the two candidates could not have been more different: speaking before packed city squares across the country in the campaign during the first round, Petro promised an imminent end to Colombia’s corruption, violence, and injustice while making darkly sarcastic asides about the privileged lives of those now in power—a combination that electrified his listeners and terrified his critics. Hernández, on the other hand, barely appeared in public until the last few weeks of the campaign. In his scant public comments, he had little to say regarding his vision for Colombian politics beyond condemning political corruption and declaring that he would jail the offenders, ratchet up investigations, and generally drain the swamp.

The conditions that drove Hernández’s unexpected rise—and that have both helped and hindered Petro’s political career—can be found in the tension between a mounting discontent with the status quo and an enduring fear of the political left. Unlike most other Latin American countries, Colombia has never been led by a socialist, in part because many previous aspirants were killed on the campaign trail: in the run-up to the 1990 elections, for instance, three leftist and liberal presidential candidates were assassinated by shady forces involving paramilitary troops, narcotraffickers, and rogue state officials. In the minds of many throughout the country, the left remains associated with Colombia’s jungle-based narcotrafficking guerrillas, the most important of which, the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), demobilized a mere five years ago. These guerrilla groups continue to loom large in the country’s political imagination: Colombia’s far-flung territories, where these groups organized and held the strongest influence, are still seen “as a set of threats,” according one former senior military leader. Colombia’s left has also been stained by the legacy of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, whose authoritarian clampdown and fiscal mismanagement have driven his oil-rich country toward economic collapse, prompting millions of migrants to flee, many to Colombia. Political conservatives sought to stall Petro’s campaign by suggesting that he could usher in similar economic and political mayhem.

Those concerns cost Petro the 2018 presidential election: he lost to the conservative stalwart Iván Duque, a disciple of the former president and security hard-liner Álvaro Uribe. Duque is leaving office with his favorability ratings mired in the 20s. Although the government’s economic and social record accounts for much of his unpopularity, this discontent can also be traced to Duque’s failure to move the country away from long-standing conflicts with armed criminal and guerrilla groups. His opposition to the 2016 peace accords forged with the FARC under former President Juan Manuel Santos—a landmark deal that aimed to release Colombia from decades of draining clashes between the state and the country’s largest guerrilla force—led to a lukewarm application of the terms of the agreement and resurgent government support for military offensives against residual armed groups, criminal outfits, and coca growers.

To his supporters, Petro is a standard-bearer for Latin American progressivism.

The results of the watered-down accords have been a disappointment to all sides. The peace agreement aimed to help former combatants demobilize and transition to civilian life, often as farmers. Former guerrillas, however, say the government has failed to make good on promises of land and aid. Rather than laying down their weapons, armed groups have multiplied and grown more inconspicuous, insidious, and effective in extracting illicit revenues and exerting their power over defenseless rural communities. As a result, Duque’s security agenda did not lead to a decline in violence but rather to an increase in instability and insecurity: according to a study by the humanitarian nonprofit Fundación Ideas para La Paz, close to 80,000 civilians were forcibly displaced last year, the largest number in 12 years. Last year’s murder rate was also the highest in close to a decade.

Yet in a strange turn of events, the same peace agreement that failed to meet its proponents’ pledges to transform rural life brought immense changes to the populous urban zones that once looked askance at talks with the FARC. Left-wing causes rooted in income and power redistribution, formerly portrayed as civilian smokescreens for insurgent forces, have found much freer expression now that the FARC’s demobilization has removed some of the stigma attached to socialism. Petro’s presidential campaign in 2018, which despite defeat represented a breakthrough showing by a left-wing candidate, was followed a year later by a monumental series of urban protests in which marchers voiced grievances regarding Colombia’s social inequities and its government’s flaws. The same marches took place last year with more fury and on a greater scale during the COVID-19 pandemic, which laid bare the consequences of the country’s enormous inequality: while members of many rich households flew to places such as Miami to receive vaccines, over 600 mostly poor Colombians were dying every day during the pandemic’s peak. Protesters were met on occasion with live fire and beatings from riot police; while insisting it respected peaceful demonstrations, the government blamed vandals, armed groups, Venezuela, and Petro himself for provoking violent disturbances. But rather than undermining Petro’s political credibility, Colombia’s wave of public unrest seems to have heightened the country’s willingness to embrace an outsider candidate who is ready to upend the social order.

The vast discrepancy in how the pandemic affected different segments of Colombian society is indicative of the country’s underlying hierarchical structure. Although its economy has undergone steady growth and is fast recovering from the pandemic, Colombia is the second most unequal country in Latin America after Brazil. Its rates of social mobility are the lowest of all 38 member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Whether it is in access to education, health care, land, or formal employment, Colombia operates according to brazenly selective and segregated systems rooted in connections, families, and, above all, money.

Inequality is even more pronounced outside the cities, especially in areas near the Pacific coast, which is home to large indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. The despair created by the prevailing lack of opportunity has long boosted recruitment by criminal and armed groups; now it is finding expression in democratic political mobilization on behalf of left-wing candidates. Petro’s vice-presidential running mate, Francia Márquez, an exceptionally brave and outspoken Black environmental and human rights activist, has gained enormous political momentum on the basis of her progressive platform. Petro’s victory signals that a majority of Colombians may be yearning to blame leaders they see as avaricious and out of touch—but now they are also willing, as they have not been before, to face the costs of undertaking difficult reforms. “If we hadn’t woken up, we would have been submissive forever,” said one young female protester in Cali to the International Crisis Group last year. “People no longer have fear.”

GOVERNING WITH A STEADY HAND

Petro will likely face immediate challenges as president. Colombia’s relations with the armed forces and with the U.S. government might deteriorate rapidly, particularly if Petro makes good on his promise to remove the current military high command, presses for a rapid change in security policy, or pushes to abandon the policy of coca eradication in favor of voluntary substitution, in which coca growers uproot the illegal crops and turn to other ventures with the help of state support. Improving ties with Cuba and Venezuela or initiating a fresh peace process with the guerrilla group the National Liberation Army (ELN), both of which could be in the cards, will invite critical scrutiny.

Yet as a matter of policy these steps are feasible, and as a matter of politics they are seemingly backed by some of Petro’s opponents. Former president Juan Manuel Santos, for instance, made great efforts to reach a deal with the ELN before leaving office, and coca substitution is an anchor of Colombia’s 2016 peace accord. Duque’s overt hostility to the Venezuelan government has not succeeded in dislodging Maduro from office, but it has fueled acute instability on the countries’ shared border. Petro’s plan to begin winding down the oil industry is more problematic and could well cause an economic shock and rapid devaluation. But it is also an expeditious way to make good on the climate change commitments that Colombia, along with other Western countries, has pledged to uphold.

Only time will tell whether Petro is truly capable of healing the country’s deep social cleavages.

Petro’s ascent to power is not a panacea for the country’s ills. Regardless of Petro’s progressive agenda, the same issues of inequity and insecurity that bedeviled Duque will in all likelihood resurge. Colombia’s main political obstacles—providing greater security in the country’s rural periphery and expanding economic opportunity in its poor suburbs—will present a challenge to Petro, particularly if he aims to wean the country off its oil exports while bolstering the state. The incoming president will face the unenviable dilemma of extracting more revenue from a limited tax base to fund his ambitious proposals. This will trigger stiff opposition: Petro may have to contend with paralysis in Congress and the flight of capital from the country. And if Colombian history is any indication, the left’s rise to power could lead to a cycle of violence against grassroots social activists by armed groups such as the narcotrafficking Gulf Clan. Whether Petro can handle these challenges and build strong coalitions without abandoning his policy goals or attempting to expand executive rule will be the crucial test over the next four years.

Colombia’s most famous son, Gabriel García Márquez, has said that the military dictator of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century is the only mythological figure created by Latin America. But what this election has demonstrated is that it is the populist of the left or the right railing against the establishment—crusading for social change, claiming to represent the people, calling for a new era of honest governance—that is now the most compelling fixture of the region’s politics. As a state that, despite its bloodstained past, has maintained a remarkably long-lived democracy, Colombia has numerous checks and balances to hem Petro in: a wide spectrum of parties in Congress, interventionist courts, autonomous watchdogs, a largely self-governing military. For anxious Colombians, these bulwarks offer an assurance of stability. But as the dust settles after this battle between populists, only time will tell whether Petro is truly capable of healing the country’s deep social cleavages—or if he will instead succumb to the populist demagoguery that has stricken so much of the region.

No comments:

Post a Comment