After a ten-month effort, researchers discovered the young endangered reptiles on a remote volcano

Jacquelyne Germain

Staff contributor

:focal(956x656:957x657)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e0/7d/e07df706-e6f4-4e5c-975f-2a81f70e6356/20220512_170031.jpg)

With seven expeditions over the past ten months, scientists in the Galápagos Islands have been studying the last surviving population of critically endangered pink iguanas. Made up of an estimated 200 to 300 adults, the population has been declining and aging over the last decade, leading to concern about the species going extinct.

Now, scientists have made a major discovery: They’ve revealed the first-ever documented nesting sites of the reptile and the first recorded pink iguana hatchlings.

The find represents the first time that baby or juvenile pink iguanas have been found since the species was identified in 2009. Previously, only older pink iguanas were seen in the region.

“This discovery marks a significant step forward, which allows us to identify a path going forward to save the pink iguana,” Danny Rueda, the director of the Galápagos National Park, says in a statement, per Reuters.

The global population of pink iguanas is confined to Isabela Island’s Wolf Volcano, the tallest volcano in the Galápagos. Dozens of cameras hidden throughout the volcano by conservationists helped document the pink iguanas’ nesting activities.

The cameras also helped identify the main predator killing young iguanas: non-native feral cats. The cats congregate near the nesting sites and kill the hatchlings, which are easy prey for the felines. Scientists suspect predation by cats has prevented young iguanas from living long enough to reproduce for the last decade. Rats observed near pink iguana nesting sites may also be a threat to the species, reports USA Today’s Saleen Martin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c5/c3/c5c328d3-1159-4187-9697-e076ea349cdb/i-expedicion_censo_iguanas_rosadas_volcan_wolf-2021_033.jpg)

Though national park rangers first discovered the reptile in 1986, scientists took decades to identify the pink iguana as its own species. Despite their name, baby pink iguanas are anything but pink. The young reptiles have a neon yellow-green color with characteristic dark striping. It’s not until the reptiles get older that they develop their rosy hue. The iguanas can grow up to 18.5 inches in length, reports Reuters.

“The discovery of the first-ever nest and young pink iguanas together with evidence of the critical threats to their survival has also given us the first hope for saving this enigmatic species from extinction.” Paul Salaman, president of Galápagos Conservancy, says in a statement. “Now, our work begins to save the pink iguana.”

The search for the endangered reptiles was part of Iniciativa Galápagos, a partnership between the Galápagos National Park Directorate and Galápagos Conservancy to preserve and restore the Ecuadorean islands.

Since finding the nesting sites and hatchlings, Iniciativa Galápagos researchers are now focused on protecting and monitoring the nesting locations. To aid in these conservation efforts, the Galápagos Conservancy funded the establishment of a field station with a 360-degree view of Wolf Volcano to defend against poaching and animal trafficking activity. “This remote base will facilitate conservation and monitoring work on the volcano, helping guarantee the conservation and restoration of the Pink Iguana population,” Rueda says in the statement.

Alongside the pink iguanas, the Galápagos are home to various other species that only exist in the region, such as the giant Galápagos tortoise, the Galápagos penguin and the marine iguana.

Army of islanders to protect gecko the size of a paperclip

COURTESY ROXANNE FROGET

COURTESY ROXANNE FROGETDressed in camouflage and combats and with self-defence training under their belts, the Union Island wardens look prepped for battle.

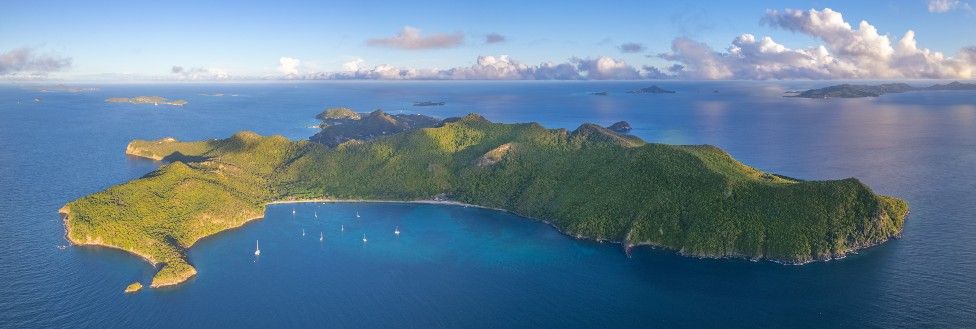

They are in fact on a mission to protect one of the world's tiniest species - one so rare it exists in just 50 hectares (123 acres) in a remote corner of one of the smallest islands in the Caribbean.

The Union Island gecko is the size of a paperclip, critically endangered and facing an insidious enemy - poachers.

Following its official discovery in 2005, the unique creature quickly became a coveted curio by collectors enthralled by its gem-like markings, earning it the dubious distinction of the most trafficked reptile in the Eastern Caribbean.

FFI/J BOCK

FFI/J BOCKThat is at least until Union islanders got involved. Since 2017, local residents trained as wardens have been patrolling the dense virgin forest of this location in St Vincent and the Grenadines, on call 24/7 in the event of an intruder.

Their work, carried out in sync with the government's forestry department and international conservationists including Fauna and Flora International (FFI), has been credited with an 80% increase in population. A recent survey indicated numbers of the gecko soared from 10,000 in 2018 to around 18,000 now - outnumbering the island's human population six-fold.

Community involvement has been key, says Glenroy Gaymes, the government's chief wildlife officer.

"A lot of people didn't even know the gecko existed," Mr Gaymes says. "We went house to house, held roadside meetings and school programmes to sensitise people. We had to go to the forest to capture one and bring it to the consultations so people knew what it was. Everyone was wowed - they were expecting something much bigger.

"It's just an inch-and-a-half long, and so pretty people were in awe."

Biodiversity haven

Roxanne Froget became Union Island's first female warden in February 2018.

COURTESY ROXANNE FROGET

COURTESY ROXANNE FROGET"When I heard about the gecko only being found on Union Island it was a wow for me. It was amazing to see it for the first time with all its colours," she recalls.

The geckos slowly change hue when brought into the light from dark brown to multi-coloured.

A nature lover, Ms Froget was keen to get involved with the project.

"We patrol the forest on a daily basis and are on call around the clock. We are protecting everything - the fauna, the flora, even the stones which people used to use for construction as they are part of the geckos' habitat. The area has to be totally untouched," she explains.

"I love being in nature, listening to the sounds of the birds. I look forward to going to work every day," the mother-of-two smiles.

FFI/ROSEMAN

FFI/ROSEMAN"My nine-year-old son loves the forest too. I tell him all about the gecko and how I help protect it. I feel so proud to be part of this work - and it's all happening on my island, my home."

In addition to active patrol training and self-defence skills - courtesy of Mr Gaymes who is a fourth degree black belt in taekwondo - wardens are taught about the many intriguing species that call the forest home and the traditional uses for medicinal plants so that they can pass their knowledge on to local schoolchildren and visitors.

What Union Island lacks in monetary wealth it makes up for in rich biodiversity. Since the gecko project began, the team has extended its work to protect a number of other endemic creatures too, like the "pink rhino" iguana, also under threat from poachers.

Both reptiles' rarity and striking colours have been their downfall.

FFI/J DALTRY

FFI/J DALTRY FFI/J HOLDEN

FFI/J HOLDEN"Most of the collectors are naturalists; they want the geckos because they are different. They want to learn how to breed them and be the first to learn about them so they can show off to their peers," explains FFI's Caribbean programme manager Isabel Vique.

Ms Vique's collectors come from as far as the US and Europe and some arrive by yacht.

FFI/J BOCK

FFI/J BOCK"But since we've been on the ground, there has been an 80% reduction in the number [of geckos] advertised online."

Poachers previously took advantage of Union islanders' friendly nature to locate the geckos' habitat.

"They would come to the island pretending to be tourists and go around asking the locals where they can see them," Ms Vique says, adding: "We have been raising awareness so now people won't tell you where to find the gecko, they will point you to the police station instead."

The gecko has been protected by international treaty CITES since 2019, thanks to the government's efforts, affording it the highest level of protection. Poachers face a hefty fine and a possible prison sentence if caught.

As one of the world's last remaining tropical dry forests, the geckos' Chatham Bay home is a "kind of living laboratory for West Indies wildlife", says FFI's project manager James Crockett.

"Caribbean dry forest is one of the most endangered habitats on the planet. Very few are undisturbed like Chatham Bay," he tells the BBC.

FFI/J DALTRY

FFI/J DALTRYAnd that makes the project all the more valuable.

"I believe the Union Island gecko is the perfect representative mascot for the island to be known by in the wider world - it's small, perfect and beautiful," Mr Crockett adds.

Roseman Adams, co-founder of local NGO the Union Island Environmental Alliance which has been at the forefront of the gecko conservation endeavours, agrees.

"Some in government still believe the area is good for a major tourism development. We have been trying to communicate the value of having this healthy, undisturbed dry forest in which we are finding more and more species new to the world," he says.

"If we lose that opportunity to find and preserve them, they will be lost forever."

For Mr Adams, the gecko has a special symbolism.

"The fact that the gecko has survived for thousands of years means it's very resilient. When it raises its tail it looks proud," he says.

"This species represents us as Unionites - we may be small but we are proud and resilient."

No comments:

Post a Comment