The Conversation

June 7, 2023

Chinese farmers harvest rice crops using combines in Xinghua in China's eastern Jiangsu province on October 23, 2017. © AFP

In some parts of the world, the rules are strict; in others they are far more lax. In some places, people are likely to plan for the future, while in others people are more likely to live in the moment. In some societies people prefer more personal space; in others they are comfortable being in close quarters with strangers.

Why do these kinds of differences exist?

There are a number of theories about where cultural differences come from. Some social scientists point to the role of specific institutions, like the Catholic Church. Others focus on historical differences in philosophical traditions across societies, or on the kinds of crops that were historically grown in different regions.

But there’s another possible answer. In a growing number of cases, researchers have found that human culture can be shaped by key features of the environments in which people live.

Just how strong is this ecology-culture connection overall? In a new study, ourlab, the Culture and Ecology Lab at Arizona State University, set out to answer this question.

How does ecology shape culture?

Ecology includes basic physical and social characteristics of the environment – such factors as how abundant resources are, how common infectious diseases are, how densely populated a place is, and how much threat there is to human safety. Variables like temperature and the availability of water can be key ecological features.

What impact does a dry climate have on the culture of the people who live in it?

Peter Adams/Stone via Getty Images

The three examples of cultural differences we started with illustrate how this can work. It turns out that the strength of social norms in a given culture is linked to the amount of threat, from such factors as war and disasters, a society faces. Stronger rules may help members of a society stick together and cooperate in the face of these dangers.

Places with less access to water tend to be more future-oriented. When fresh water is scarce, the thinking goes, there is more need to plan so that it doesn’t run out.

And in places with colder temperatures people feel less need for lots of personal space in public, perhaps because there tend to be fewer germs, or maybe from an impulse, on some basic level, to keep warm.

All of these examples show that cultures are shaped, at least in part, by the basic features of the environments people live in. And in fact, there are many other examples in which researchers have linked particular cultural differences to particular differences in ecology.

Quantifying the connection

For over 200 societies, we gathered comprehensive data on nine key features of ecology – such as rainfall, temperature, infectious disease and population density – and dozens of aspects of human cultural variation – including values, strength of norms, personality, motivation and institutional characteristics. With this information, we created the open-access EcoCultural Dataset.

Using this data set, we were able to generate a range of estimates for just how much of human cultural variation can be explained by ecology.

We ran a series of statistical models looking at the relationship between our ecological variables and each of the 66 cultural outcomes we tracked. For each of the cultural outcomes, we calculated the average amount of the cultural diversity across societies that was explained by this combination of nine different ecological factors. We found that nearly 20% of cultural variation was explained by the combination of these ecological features.

Importantly, our statistical estimates take into account common issues in cross-cultural research. One complicating factor is that societies that are close to each other in space will be similar in ways beyond the variables measured in any particular study. In the same way, there will likely be unmeasured similarities between societies with shared historical roots. For example, cultural similarities between southern Germany and Austria may be accounted for by their shared cultural and linguistic heritage, as well as similar climates and levels of wealth.

Twenty percent may not sound impressive, but in fact this is several times larger than the average effect in our field of social psychology, in which typically up to around 4% or 5% of the variation in an outcome is explained.

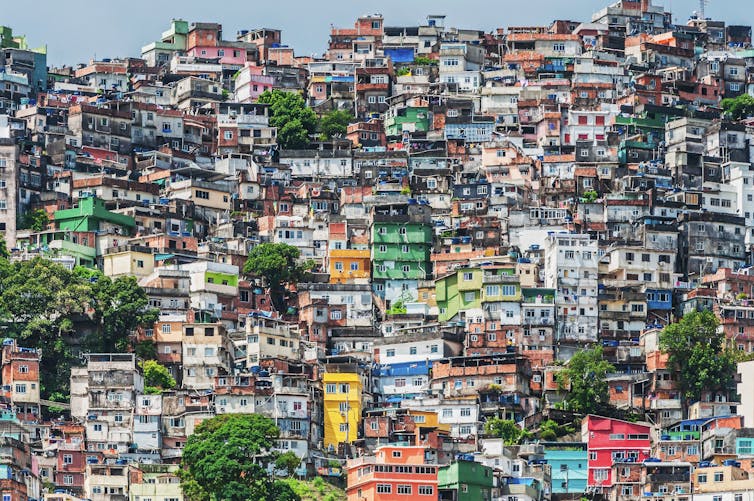

Population density is one factor that can leave its mark on a place’s culture.

The three examples of cultural differences we started with illustrate how this can work. It turns out that the strength of social norms in a given culture is linked to the amount of threat, from such factors as war and disasters, a society faces. Stronger rules may help members of a society stick together and cooperate in the face of these dangers.

Places with less access to water tend to be more future-oriented. When fresh water is scarce, the thinking goes, there is more need to plan so that it doesn’t run out.

And in places with colder temperatures people feel less need for lots of personal space in public, perhaps because there tend to be fewer germs, or maybe from an impulse, on some basic level, to keep warm.

All of these examples show that cultures are shaped, at least in part, by the basic features of the environments people live in. And in fact, there are many other examples in which researchers have linked particular cultural differences to particular differences in ecology.

Quantifying the connection

For over 200 societies, we gathered comprehensive data on nine key features of ecology – such as rainfall, temperature, infectious disease and population density – and dozens of aspects of human cultural variation – including values, strength of norms, personality, motivation and institutional characteristics. With this information, we created the open-access EcoCultural Dataset.

Using this data set, we were able to generate a range of estimates for just how much of human cultural variation can be explained by ecology.

We ran a series of statistical models looking at the relationship between our ecological variables and each of the 66 cultural outcomes we tracked. For each of the cultural outcomes, we calculated the average amount of the cultural diversity across societies that was explained by this combination of nine different ecological factors. We found that nearly 20% of cultural variation was explained by the combination of these ecological features.

Importantly, our statistical estimates take into account common issues in cross-cultural research. One complicating factor is that societies that are close to each other in space will be similar in ways beyond the variables measured in any particular study. In the same way, there will likely be unmeasured similarities between societies with shared historical roots. For example, cultural similarities between southern Germany and Austria may be accounted for by their shared cultural and linguistic heritage, as well as similar climates and levels of wealth.

Twenty percent may not sound impressive, but in fact this is several times larger than the average effect in our field of social psychology, in which typically up to around 4% or 5% of the variation in an outcome is explained.

Population density is one factor that can leave its mark on a place’s culture.

More left to discover

In testing over 600 relationships among features of ecology and culture, we identified a number of intriguing new relationships. For example, we found that the amount of variation over time in levels of infectious disease was linked to the strength of social norms. This link suggests that it’s not just places with high levels of threat from germs, but also places where that threat varies more over time, such as India, that have stricter social rules.

There’s also a growing body of research suggesting that as the ecology of a place changes, so too does the culture. For example, a general decline in rates of infectious disease in the U.S., up until the current pandemic, is correlated with a loosening of social norms over the past century. Similarly, increases in population density appear to be linked to declines in birth rates around the world in the past several decades.

Because the EcoCultural Dataset contains not only contemporary measures of ecology, but also information about their variability and predictability over time, we believe it will be a rich resource for other scholars to mine. We’ve made all of this data free for anyone to accessand explore.

Ecology isn’t the only reason people around the world think and behave differently. But our work suggests that, at least in part, our environments shape our cultures.

Alexandra Wormley, Ph.D. Student in Social Psychology, Arizona State University and Michael Varnum, Associate Professor of Psychology, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In testing over 600 relationships among features of ecology and culture, we identified a number of intriguing new relationships. For example, we found that the amount of variation over time in levels of infectious disease was linked to the strength of social norms. This link suggests that it’s not just places with high levels of threat from germs, but also places where that threat varies more over time, such as India, that have stricter social rules.

There’s also a growing body of research suggesting that as the ecology of a place changes, so too does the culture. For example, a general decline in rates of infectious disease in the U.S., up until the current pandemic, is correlated with a loosening of social norms over the past century. Similarly, increases in population density appear to be linked to declines in birth rates around the world in the past several decades.

Because the EcoCultural Dataset contains not only contemporary measures of ecology, but also information about their variability and predictability over time, we believe it will be a rich resource for other scholars to mine. We’ve made all of this data free for anyone to accessand explore.

Ecology isn’t the only reason people around the world think and behave differently. But our work suggests that, at least in part, our environments shape our cultures.

Alexandra Wormley, Ph.D. Student in Social Psychology, Arizona State University and Michael Varnum, Associate Professor of Psychology, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment