Annotations in eighth-century manuscript point to work of revered English monk, scholar and saint

Dalya Alberge

Sat 16 Sep 2023

His life of service through scholarship earned him the title “venerable”. He is considered one of the most influential thinkers of the post-Roman world, and acknowledged as a saint in the Orthodox, Catholic and Anglican traditions.

Now a leading academic believes she has identified an example of the handwriting of Bede, the medieval theologian revered as the father of English history, along with his “lost” Old English translation of the St John’s Gospel.

His life of service through scholarship earned him the title “venerable”. He is considered one of the most influential thinkers of the post-Roman world, and acknowledged as a saint in the Orthodox, Catholic and Anglican traditions.

Now a leading academic believes she has identified an example of the handwriting of Bede, the medieval theologian revered as the father of English history, along with his “lost” Old English translation of the St John’s Gospel.

A stained glass window depicting the Venerable Bede at St Nicholas church in Blakeney, Norfolk.

Photograph: ASP Religion/Alamy

Michelle Brown, the British Library’s former curator of illuminated manuscripts, told the Observer that extensive evidence within two manuscripts makes a compelling and exciting case for linking them to the eighth-century monk and scholar of the monastery of Wearmouth and Jarrow near Newcastle.

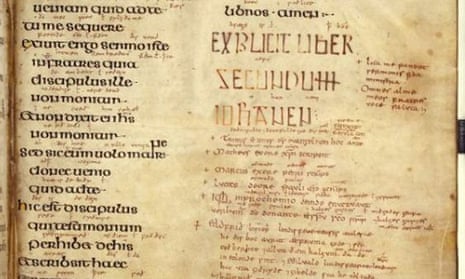

In the preface to the Book of Kings in the Codex Amiatinus – a Bible that was taken to Rome from Jarrow in 715 and is now in a Florentine archive – she found parallels between grammar and linguistics within annotated passages and Bede’s published writings.

Noting the sophistication of an exceptional scholar rather than a mere scribe, she singled out complex Greek letter-forms in the margins and a distinctive “lightning flash” that Bede pioneered to highlight quotations.

She said: “We know that Bede knew Greek. Not that many people did know Greek at that time. So we’ve got the marginalia and the way in which he marks up. The little zigzag lines that look like lightning flashes he invented like a yellow magic marker to indicate when he was quoting a passage – a passage of the Old Testament period in the New Testament, for example. So it’s got these mark-ups that he’s only inventing around this period.”

She argued that the use of Greek and Hebrew, as well as marginal reference annotations, reflect Bede’s interests and practices: “We also know from his own admission that he was ‘author, notary and scribe’ and would have mastered the gamut of the Insular system of scripts, as this hand had.

“He was referring to the Old Testament use of the word scribe as a priestly function for writing scripture … Given that Codex Amiatinus … [was] such an incredible intellectual feat, it is unthinkable that Bede’s hand would not be present.”

She added that a number of the scribes left colophons – publisher’s emblems – at the end of their contributions which say, “Pray for me”. “But the one that I think is Bede doesn’t … He emphasises in his colophon, ‘labore’ (work), and that’s something that throughout his autobiographical writings and elsewhere Bede always stresses – the sanctity of the work. So the colophon sections by this particular hand point to a different take … than that of the other scribes.”

On his deathbed in 735, Bede translated the Gospel of St John into Old English, the first time that a western vernacular language other than Latin had been used to record any part of the Bible.

The original work has not survived but Brown argues that sections were added to the Lindisfarne Gospels around 950, as she has identified evidence such as “characteristic Bedan marginal quotation marks”.

Michelle Brown, the British Library’s former curator of illuminated manuscripts, told the Observer that extensive evidence within two manuscripts makes a compelling and exciting case for linking them to the eighth-century monk and scholar of the monastery of Wearmouth and Jarrow near Newcastle.

In the preface to the Book of Kings in the Codex Amiatinus – a Bible that was taken to Rome from Jarrow in 715 and is now in a Florentine archive – she found parallels between grammar and linguistics within annotated passages and Bede’s published writings.

Noting the sophistication of an exceptional scholar rather than a mere scribe, she singled out complex Greek letter-forms in the margins and a distinctive “lightning flash” that Bede pioneered to highlight quotations.

She said: “We know that Bede knew Greek. Not that many people did know Greek at that time. So we’ve got the marginalia and the way in which he marks up. The little zigzag lines that look like lightning flashes he invented like a yellow magic marker to indicate when he was quoting a passage – a passage of the Old Testament period in the New Testament, for example. So it’s got these mark-ups that he’s only inventing around this period.”

She argued that the use of Greek and Hebrew, as well as marginal reference annotations, reflect Bede’s interests and practices: “We also know from his own admission that he was ‘author, notary and scribe’ and would have mastered the gamut of the Insular system of scripts, as this hand had.

“He was referring to the Old Testament use of the word scribe as a priestly function for writing scripture … Given that Codex Amiatinus … [was] such an incredible intellectual feat, it is unthinkable that Bede’s hand would not be present.”

She added that a number of the scribes left colophons – publisher’s emblems – at the end of their contributions which say, “Pray for me”. “But the one that I think is Bede doesn’t … He emphasises in his colophon, ‘labore’ (work), and that’s something that throughout his autobiographical writings and elsewhere Bede always stresses – the sanctity of the work. So the colophon sections by this particular hand point to a different take … than that of the other scribes.”

On his deathbed in 735, Bede translated the Gospel of St John into Old English, the first time that a western vernacular language other than Latin had been used to record any part of the Bible.

The original work has not survived but Brown argues that sections were added to the Lindisfarne Gospels around 950, as she has identified evidence such as “characteristic Bedan marginal quotation marks”.

She also noted the omission of disciples, such as Thomas, that are given in the Latin text, and the addition of the names of the sons of Zebedee, though they are not given in the text: “It seems more consistent with Bede’s rapid translation work, introducing some short cuts due to pressure of time, with death approaching fast, and interpolating some details from memory.”

Brown, who worked at the British Library for 28 years, is professor emerita of medieval manuscript studies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

She said of the evidence: “You haven’t got a smoking quill. It doesn’t say ‘Bede’. But put all the evidence together and I think this is as good an argument as has been advanced.”

Her discoveries will feature in a new book, titled Bede and the Theory of Everything, to be published by Reaktion Books in October.

Brown, who worked at the British Library for 28 years, is professor emerita of medieval manuscript studies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

She said of the evidence: “You haven’t got a smoking quill. It doesn’t say ‘Bede’. But put all the evidence together and I think this is as good an argument as has been advanced.”

Her discoveries will feature in a new book, titled Bede and the Theory of Everything, to be published by Reaktion Books in October.

No comments:

Post a Comment