OTTAWA — A retired RCMP investigator who examined a seized laptop computer said he was "totally shocked" to discover someone had sent sensitive intelligence documents to a criminal suspect.

Former RCMP staff sergeant Guy Belley described Wednesday in Ontario Superior Court how the revelation set off alarm bells five years ago.

Belley, who retired in 2020, was the first Crown witness in the judge-and-jury trial of Cameron Jay Ortis, a former RCMP intelligence director accused of disclosing classified material.

Ortis is charged with violating the Security of Information Act by allegedly revealing secrets to three individuals in 2015 and trying to do so in a fourth instance, as well as breach of trust and a computer-related offence.

Ortis, 51, has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

The charges against Ortis claim he communicated "special operational information" without authority while designated as a person "permanently bound to secrecy" — a category that includes numerous officials in the Canadian security and intelligence community.

At the time, Ortis was away on language training after serving as director of an operations research unit staffed by analysts. Upon his return in 2016, he became director general of the RCMP's National Intelligence Co-ordination Centre.

Belley was tasked in 2018 with analyzing the contents of a laptop computer owned by Vincent Ramos, chief executive officer of Phantom Secure Communications, who had been arrested in the United States.

An RCMP effort known as Project Saturation revealed that members of criminal organizations were known to use Phantom Secure's encrypted communication devices.

Ramos would later plead guilty to using his Phantom Secure devices to help facilitate the distribution of cocaine and other illicit drugs to countries including Canada.

Belley told the court he found an email to Ramos from an unknown sender with portions of 10 documents, including mention of material from Canada's anti-money laundering agency.

The sender would later offer to provide Ramos with the full documents in exchange for $20,000.

The Crown says the RCMP uncovered evidence, after much technical sleuthing, that Ortis had communicated secrets to Ramos and other investigative targets.

A statement of agreed facts, filed as an exhibit in the case, says the material in question was "special operational information" as defined by Canada's secrets law.

Associated exhibits include details of email messages in the first half of 2015, sent anonymously to Ramos, offering to provide information of interest.

The Crown is expected to spend the next several days of the trial trying to persuade the jury that Ortis was behind the overtures, ultimately breaching the Security of Information Act.

An April 29, 2015, email to Ramos from the email account variablewinds@tutanota.de said the various attachments were partial copies of U.S. and Canadian law enforcement intelligence targeting Phantom Secure.

"They are embargoed in that I've removed the body of these documents leaving enough remaining to allow you to assess whether or not you would be interested in acquiring the unembargoed full documents," the email reads.

"Phantom Secure is of considerable interest to both law enforcement and intelligence agencies in the western world. The documents attached here are only a selection of the broader effort against your organization. The ultimate goal is to get at your clients, some of whom are significant global actors.

"Your service has stymied action against them. Thus, their goal is to disrupt or dismantle Phantom Secure."

Among the documents offered were disclosures from the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada to law enforcement, as well as police intelligence assessments of Phantom Secure.

An earlier anonymous email to Ramos, on March 21, asked if Kapil Judge, Phantom Secure's technical manager, had "met someone friendly" while undergoing a secondary border services agency inspection at the airport.

In an interview with police, Ramos acknowledged receiving and engaging in the email correspondence.

The RCMP then began trying to figure out who had sent the mysterious emails to Ramos.

In 2019, the Mounties determined that in March 2015, Ortis had used the RCMP National Crime Data Bank database to access a March 6 Mountie report from that year outlining a plan to have an undercover police officer approach Judge at the Vancouver Airport.

Ortis was taken into custody in September 2019.

Search warrants were executed at his apartment in Ottawa's Byward Market neighbourhood and at his office at RCMP headquarters, says the statement of agreed facts.

Investigators seized numerous devices, including five laptop computers, five external hard drives, 10 memory keys and three cell phones.

Some portions of an encrypted memory key found at his apartment were successfully unscrambled. The key had a folder named The Project which contained several subfolders.

One document entitled Email-addresses.txt in The Project folder listed the email addresses and passwords for nine accounts including the variablewinds account, the agreed statement adds.

The RCMP were able to use the login credentials to log in to the variablewinds account and locate the emails exchanged with Ramos's Tutanota account, the statement says.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 4, 2023.

Jim Bronskill, The Canadian Press

Story by Alex Boutilier • GLOBAL NEWS

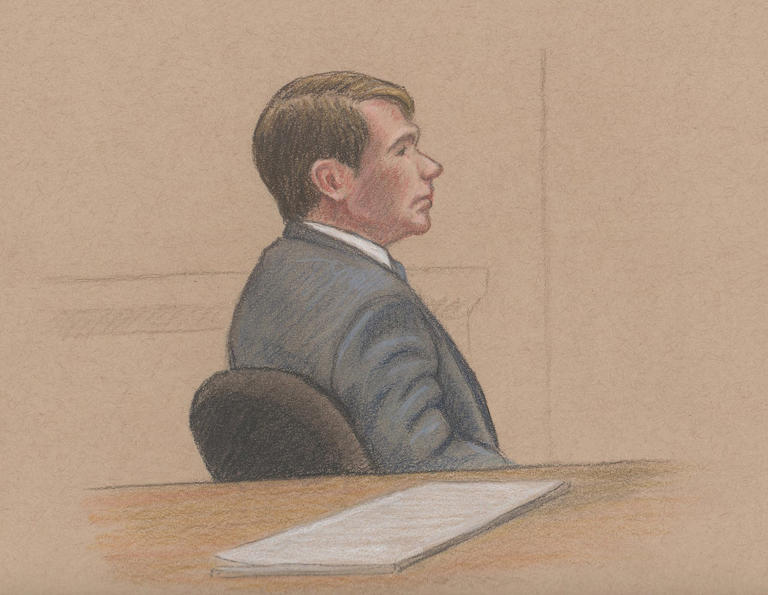

Cameron Jay Ortis, right, a former RCMP intelligence director accused of disclosing classified information, returns to the Ottawa Courthouse during a break in proceedings in Ottawa, on Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023.

When police raided Cameron Ortis’ Ottawa apartment in 2019, they say they found an encrypted USB drive that included internal RCMP documents and email correspondence with alleged criminals.

In a folder labeled “The Project,” police allegedly found snippets of documents sent to Vincent Ramos – the convicted CEO of encrypted communications service Phantom Secure – as well as email correspondence with Ramos, whose company sold untraceable smartphones. Those emails included snippets of RCMP documents relating to an investigation into encrypted communications providers, and a demand of $20,000 to turn over the full goods.

The USB drive also allegedly included “scripts” of planned conversations with Ramos and other targets of international police investigations.

Police say one file was labeled “What Was Sent.”

Those were among the now-reportable revelations outlined by Crown Prosecutor Judy Kliewer on the opening day of the trial of Cameron Ortis, a high-ranking ex-RCMP intelligence official accused of leaking secret police intelligence.

Ortis’ access to top-level intelligence is part of what makes his case “very unique,” in Kliewer’s words. It’s the first time someone who was dubbed “permanently bound to secrecy” has been tried for breaking Canada’s official secrets law.

Ortis is facing four counts of breaching the Security of Information Act, Canada’s official secrets law, as well as breach of trust and the misuse of a computer service. The trial comes four years after Ortis’ arrest, and more than five years after police began investigating a potential leak at the highest levels of RCMP intelligence.

Video: Cameron Ortis case: Intelligence director accused of selling secrets to global money laundering network

The 51-year-old has pleaded not guilty, and the charges have yet to be tested in court.

Ortis sat in an Ottawa courtroom as Kliewer made her opening submissions to the 12-person jury that will ultimately decide his fate.

A former civilian RCMP intelligence analyst, Ortis had a meteoric rise within the national police force, ultimately reaching the level of director-general at the Mounties’ National Intelligence Coordination Centre (NICC).

From his perch at the RCMP’s national headquarters, Ortis had “unlimited, unrestricted” access to information on police investigations across Canada. He also had access to a top secret database of intelligence shared by Canada’s Five Eyes security partners, as well as intelligence shared with those partners by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE).

“In this trial, you may be surprised, but there’s not very much in dispute,” in terms of the facts of the case, Kliewer told the jury.

There’s no dispute that Ortis was bound to secrecy in his role as an intelligence analyst and RCMP manager, or that the information he’s alleged to have leaked constitutes what’s called “special operational information.”

What the case will turn on, according to Ortis’ defence lawyers, is whether the former RCMP official had the authority to release that information.

“That’s really going to be the crux of the case, both for the Crown and the defence,” Jon Doody, one of Ortis’ lawyers, said in an interview with Global News on Friday.

“The Crown is going to try to prove that he didn’t have the authority (to release the information), and we’re going to demonstrate he did.”

Cameron Ortis case: Report accuses RCMP of ‘clear failure’ in leadership

Ortis’ arrest stemmed from an international police investigation into Ramos whose company, Phantom Secure, sold untraceable smartphones to criminal organizations hoping to evade police surveillance. The company was eventually dismantled by authorities in the U.S., Canada, Australia, Hong Kong and Thailand in 2018.

According to the Crown, an RCMP officer sifting through the contents of Ramos’ emails discovered someone using an anonymous email was offering to sell information about police intelligence on Phantom Secure to Ramos. The Crown said the email chain included snippets of RCMP documents about the investigation into encrypted communications services with an ask of $20,000 for the full document.

Kliewer told the jury Ramos was also given information on an undercover investigator tasked with making contact with him.

It took 18 months for the trail to lead police to Ortis.

On the USB drive found in Ortis’ apartment were other secret RCMP documents and “scripts” for communications with other targets of international police investigations, Kliewer told the jury. Kliewer said the RCMP confirmed that three other people had received correspondence detailed on the USB drive.

The trial is expected to run roughly eight weeks, with Ortis expected to take the stand in his own defence towards the end.

Crown alleges former RCMP director Cameron Ortis was trying to sell secrets to police targets

Story by Catharine Tunney •CBC

Cameron Ortis, the former RCMP intelligence official accused of breaking Canada's secret intelligence law, was trying to sell RCMP operational information to individuals linked to the criminal underworld — including targets of police investigations — the Crown team said in its opening remarks Tuesday.

Crown prosecutor Judy Kliewer told the jury on the first day of the trial that they would be weighing a "highly unusual case."

Earlier in the day, Ortis — who served as the director of the RCMP's national intelligence co-ordination centre in Ottawa at the time of his arrest — entered a not guilty plea on all charges against him. He stood tall, with his chin up, as he entered his pleas.

He faces six charges, including four counts of violating the Security of Information Act.

The 51-year-old is accused of three counts of sharing special operational information "intentionally and without authority" and one count of attempting to share special operational information. He also faces two Criminal Code charges: breach of trust and unauthorized use of a computer.

"What makes this case interesting is not only was Mr. Ortis a man permanently bound by secrecy, but he was one of the highest ranking," Kliewer said.

She told the jury that in 2013, police forces around the world were becoming increasingly concerned about criminal organizations using encrypted phones to conceal their business.

"Law enforcement around the world were going dark on criminals," Kliewer said.

At the time, she said, the RCMP had its eyes on a Vancouver-based company called Phantom Secure, which it believed was providing encrypted phones at a price. The force had launched Project Saturation but was making little progress, she said.

That changed in 2018 when the FBI was closing in on Vincent Ramos, the CEO of Phantom Secure Communications. When they arrested him in Las Vegas that year, Kliewer said, the RCMP was invited to go through Ramos's computer.

That's when the RCMP noticed something "strange and alarming," said Kliewer.

She said the investigating officer found a 2015 email from an unnamed sender with 10 attachments he recognized as RCMP documents.

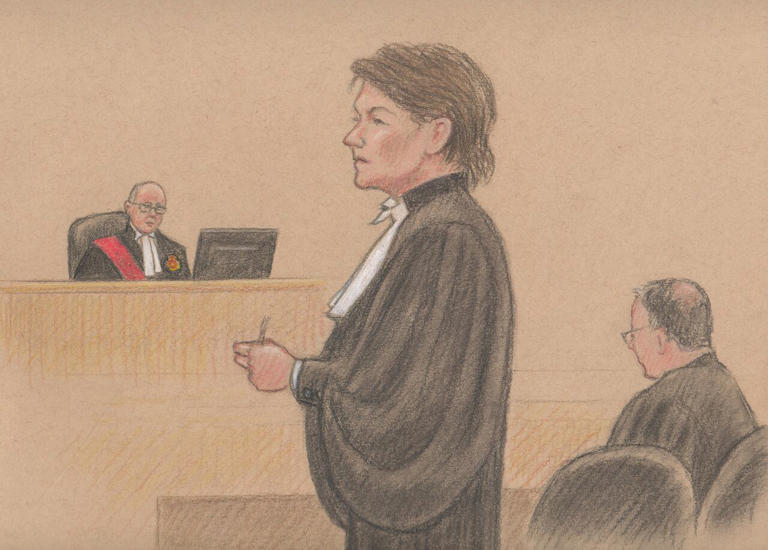

Crown prosecutor Judy Kliewer makes her opening statement in the trial of Cameron Ortis on Tuesday, Oct. 2, 2023. (Sketch by Lauren Foster-MacLeod)© Provided by cbc.ca

Kliewer told the jury the sender was asking for $20,000 in exchange for more information.

"It was quite evident that Mr. Ramos had received from this author information that disclosed the identity of an undercover operator that had been asked to approach Mr. Ramos's associate," said Kliewer.

"All of this, it's not disputed, was special operational information."

Kliewer said it took about 18 months for police to conclude it was Ortis who had sent the documents, leading to his arrest in the fall of 2019.

But that's not where the investigation ended, Kliewer said.

She said police combed through Ortis's home and office and found an encrypted USB drive that they were able to partially decrypt.

The Crown alleges police found a folder called "The Project," which included the documents sent to Ramos and scripts for communications with Ramos.

"Unfortunately, that's not all they found," said Kliewer.

"Police found documents, RCMP documents, emails and scripts for communications to more targets of international police investigation."

Cameron Ortis, a former RCMP intelligence director accused of disclosing classified information, sits and listens to jury selection in his trial at the Ottawa Courthouse on Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023. (Sketch by Lauren Foster-MacLeod)© Provided by cbc.ca

Around 2015, Kliewer said, the Five Eyes alliance — an intelligence sharing network made up of the U.S., the U.K., Canada, Australia and New Zealand — had identified a common international threat: a money laundering network headed by Altaf Khanani.

The U.S. Treasury Board has said Khanani's organization "launders illicit funds for organized crime groups, drug trafficking organizations, and designated terrorist groups throughout the world."

At the time, the RCMP was investigating three people in the Toronto area who were running money service businesses and "it was believed that they had links to the Khanani network," said Kliewer. One of those was a man named Farzam Mehdizadeh.

Related video: Former RCMP director was trying to sell secrets to police targets, Crown alleges (cbc.ca) Duration 1:37 View on Watch

She said police found documents and scripts on the USB drive from Ortis's place sent to Khanani's associates Salim Hanareh and Muhammad Ashraf. She said they found another set of documents and a cover letter that was meant to be sent to Mehdizadeh's son.

The jury heard that an RCMP investigator was able to track down Hanareh and Ashraf and confirm the documents had been sent.

Question of authority

Kliewer told the jury that many of the facts in the case have been agreed to by both sides. Ortis is permanently bound by secrecy and there is no question that "the information communicated was special operational information," she said.

"Most of what I told you is not in dispute," Kliewer said. "The issue appears to be whether what he did was with authority, whether he was authorized to communicate what he did."

Orti's lawyers have not yet made their case in court, but outside the courtroom, his lawyer Mark Ertel said his client is looking forward to testifying in the coming weeks.

"We believe he has a compelling story and that he won't be found guilty of any charges," Ertel said.

"He's charged with doing things without authority and we believe that we'll be able to establish that he did have authority to do everything he did."

Kliewer said there are no records that Ortis was tasked with a covert undercover operation.

She told the jury they'll hear from his colleagues and his superiors that "no one had any idea of what Mr. Ortis was doing by communicating to these persons in 2015."

Kliewer also noted that Ortis was on leave for French-language training when he sent most of the anonymous emails.

Mounties could testify as witnesses

As the defendant walked into court Tuesday morning, he told reporters he felt good and smiled at the cameras.

On Tuesday morning, 12 jurors and two alternates were selected. By 2 p.m., one juror had dropped out.

Two high-profile Mounties could take the stand during the trial. Former RCMP commissioner Bob Paulson and the current commissioner, Mike Duheme, who previously oversaw federal policing, are on the witness list read out to potential jurors Tuesday morning.

Cameron Ortis was previously director general of the RCMP's national intelligence co-ordination centre in Ottawa. (Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press)© Provided by cbc.ca

The RCMP has said given his role, Ortis had access to national and multinational investigations and coveted intelligence.

"This is extremely unprecedented," said Jess Davis, a former analyst at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service. "Ortis is someone who held a very high position in a very sensitive part of the RCMP.

"It's shaken the core of the public service and the security and intelligence community because this is someone who lots of people had contact with, lots of people would have had opportunity to work with."

Cameron Jay Ortis, right, a former RCMP intelligence director accused of disclosing classified information, returns to the Ottawa Courthouse during a break in proceedings in Ottawa, on Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023. (Spencer Colby/Canadian Press)© Provided by cbc.ca

Davis, now president of Insight Threat Intelligence, said she'll be watching to see the evidence the Crown presents about possible motive, whether the RCMP employed proper checks and balances to protect its intelligence and how the defence makes its case.

Security of Information Act charges are rare

This will be the first time a court tests charges under the Security of Information Act.

"It's pretty groundbreaking," said Leah West, who practises national security law and teaches at Carleton University's Norman Paterson School of International Affairs.

"Not only is it a test case, there could be a lot of lessons learned for how to deal with intelligence-to-evidence cases in other contexts, where we want to prosecute other national security cases."

There's only been one conviction under the Security of Information Act in the 21-year-old law's history. A Canadian naval officer pleaded guilty in 2012 to selling secrets to Russia during a preliminary hearing.

"Charges are super rare. Convictions are rare. Trials are the rarest," said West.

It's taken more than four years for Ortis's case to make it to trial.

He was arrested in September of 2019 and held behind bars for more than three years. He was released on bail in December under strict conditions.

Ortis's trial was held up when his original lawyer, Ian Carter, was appointed a judge to the Superior Court of Justice in Ontario in Ottawa last year. His new lawyers, Ertel and Jon Doody, needed time to catch up.

Judge has a balancing act: national security lawyer

The Federal Court had to determine which sensitive items of information could be disclosed under the Canada Evidence Act.

Davis said it's likely the public will never see the full picture, given the national security concerns.

"There's plenty of things that Canadians will just never know," she said.

"But we'll still get a good view of internal processes at the RCMP, a good sense of the investigation and at the end of the day, we'll get a verdict."

West said Justice Robert Maranger will have to constantly balance the need to protect national security information with the accused's right to a fair trial.

"The judge has to balance the need to continue to protect that information that was allegedly disclosed without authorization … with the open court principle and our right as the public to understand, and the right of the accused to know all of the information that's been used against [them]," she said.

Ortis's trial could run between four and eight weeks.

No comments:

Post a Comment