US climate assessment lays out growing threats, opportunities as temperatures rise

November 14, 2023

By Timothy Gardner

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Climate change harms Americans physically, mentally and financially, often hitting those who have done the least to cause it, including Black people facing floods in the South and minorities enduring searing heat in cities, a federal report said on Tuesday.

More than a dozen U.S. agencies and about 500 scientists produced the National Climate Assessment, meant to crystallize the top science on the problem and communicate it to wide audiences.

This year set a record for extreme weather events that cost over $1 billion, with costly floods, fires and storms occurring roughly every three weeks. In the 1980s, by comparison, the United States experienced a billion-dollar disaster only once every four months.

Climate change is increasingly imposing costs on Americans, as prices rise for weather-related insurance or certain foods. Medical costs are also going up as more people struggle with climate consequences such as extreme heat, the report said.

The assessment marks the fifth such report released by the U.S. government since 2000. It was peer-reviewed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

Atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe, a report coauthor since the second assessment, said the newest version reflects the latest in climate science and can help policymakers and companies working on emissions cuts and ways of adapting to the consequences of a warming world.

"Today, we can document the risks that we face, per degree of warming," Hayhoe told reporters on a call. "We can put a number on the extent to which climate change is fueling our record-breaking weather extremes, and we are starting to tap the interconnectivity and understand the vulnerability of our systems from socioeconomics to national security."

It was the first report produced since 2018, when the administration of then-President Donald Trump was dismantling rules meant to rein in climate-warming emissions. Trump, a Republican who denies the science of climate change, also dismissed the 2018 assessment.

Later on Tuesday President Joe Biden, a Democrat, will speak about the report, which a White House official said was the most comprehensive assessment yet on the state of climate change in the U.S. Biden will also announce more than $6 billion in funding for climate resilience projects including bolstering the power grid and reducing flood risks, the official said.

POVERTY LINE

For the first time, this year's assessment includes a chapter on economics that illustrates how costly damages are distributed unevenly across society, often amplifying existing inequalities.

Children are reporting mental-health distress due to climate anxiety. Outdoor workers suffering dehydration through extreme heat are suffering acute kidney illness after only one day of exposure to extreme temperatures, the report says.

"Families living below the poverty line often live where climatic changes are expected to be the most economically damaging, like the already-hot Southeast," the report says.

The report also said, referring to the U.S. Southeast, that slavery, segregation and housing discrimination have resulted in many Black and other minority communities living in neighborhoods exposed to environmental risks and with fewer resources to address them compared to white neighborhoods.

It was not all doom and gloom, though. With shuttered coal plants being replaced by natural gas and renewables, the country's energy-related greenhouse gas emissions fell some 12% between 2005 and 2019 - even as the economy and population both grew.

"We're pointing in the right direction, we just want to do more, faster," said Ted Schuur, a professor of ecosystem ecology at Northern Arizona University who was not involved in writing the report.

The study's findings could encourage local and state policymakers to consider ways of adapting to the coming climate disruption, such as redesigning sewer systems to better drain water from flood-prone city streets, creating cooling centers in heat-vulnerable cities or helping hospitals plan for likely increases in vector-borne diseases, as warming encourages mosquitoes and ticks to move north into new areas.

The report also discusses national security risks of climate change, as countries compete for resources needed in the energy transition. Competition with China for minerals, for example, will likely escalate tensions between the two countries in coming years.

Climate migration, meanwhile, is expected to become a high-security risk by 2030 as people living in climate-vulnerable nations seek to cross the border into the United States for safety, the report says.

The report will be translated into Spanish for the first time by early next year.

(Reporting by Timothy Gardner in Washington; Editing by Katy Daigle and Matthew Lewis)

In fight to curb climate change, a grim report shows world is struggling to get on track

SETH BORENSTEIN

November 14, 2023

The world is off track in its efforts to curb global warming in 41 of 42 important measurements and is even heading in the wrong direction in six crucial ways, a new international report calculates.

The only bright spot is that global sales of electric passenger vehicles are now on track to match what’s needed — along with many other changes — to limit future warming to just another couple tenths of a degree, according to the State of Climate Action report released Tuesday by the World Resources Institute, Climate Action Tracker, the Bezos Earth Fund and others.

On the flip side, public money spent to create more fossil fuel use is going in the wrong direction and faster than it has in the past, said study co-author Kelly Levin, science and data director at the Bezos Earth Fund.

“This is not the time for tinkering around the edges, but it’s instead the time for radical decarbonization of all sectors of the economy,” Levin said.

“We are woefully off track and we are seeing the impact of inaction unfold around the world from extensive wildfire fires in Canada, heat-related deaths across the Mediterranean, record high temperatures in South Asia and so on," she said.

Later this month, crucial international climate negotiations start in Dubai that include the first time world negotiators will do a global stocktake on how close society is to meeting its 2015 climate goals. In advance of the United Nations summit, numerous reports from experts are coming out assessing Earth’s progress or mostly the lack of it, including a United States national assessment with hundreds of indicators. Tuesday’s 42 indicators offers one of the grimmest report cards, detailing multiple failures of society.

The report looks at what’s needed in several sectors of the global economy — power, transportation, buildings, industry, finance and forestry — to fit in a world that limits warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) over pre-industrial times, the goal the world adopted at Paris in 2015. The globe has already warmed about 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) since the mid 19th century.

Six categories — the carbon intensity of global steel production, how many miles passenger cars drive, electric buses sold, loss of mangrove forests, amount of food waste and public financing of fossil fuel use — are going in the wrong direction, the report said.

“Fossil fuel consumption subsidies in particular reached an all-time high last year, over $1 trillion, driven by the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy price spikes,” said report co-author Joe Thwaites of the Natural Resources Defense Council environmental group.

Another six categories were considered “off track” but going in the right direction, which is the closest to being on track and better than the 24 measurements that are “well off track.” Those merely off track include zero-carbon electricity generation, electric vehicles as percentage of the fleet, two- and three-wheel electric vehicle sales, grazing animal meat production, reforestation and share of greenhouse gas emissions with mandatory corporate climate risk reporting requirements.

People should be worried that this report is one of ’’too little, too late,” said University of Arizona climate scientist Katharine Jacobs, who wasn’t part of the report but praised it for being so comprehensive.

“I am not shocked that at a global scale we are not meeting expectations for reducing emissions,” Jacobs said in an email. “We cannot ignore the fact that global commitments to (greenhouse gas) reductions are essentially unenforceable and that a number of major setbacks have taken a toll on our progress.”

When trying to change an economy, the key is to start with “low-hanging fruit, i.e., the sectors of the economy that are easiest to transition and give a big bang for your buck,” said Dartmouth climate scientist Justin Mankin, who isn’t part of the report. But he said the report shows “we’re really struggling to pick the low-hanging fruit.”

___

This story corrects Katharine Jacobs’ affiliation to University of Arizona, not Arizona State.

___

Read more of AP’s climate coverage at http://www.apnews.com/climate-and-environment.

___

Follow Seth Borenstein on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @borenbears

___

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

November 14, 2023

By Timothy Gardner

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Climate change harms Americans physically, mentally and financially, often hitting those who have done the least to cause it, including Black people facing floods in the South and minorities enduring searing heat in cities, a federal report said on Tuesday.

More than a dozen U.S. agencies and about 500 scientists produced the National Climate Assessment, meant to crystallize the top science on the problem and communicate it to wide audiences.

This year set a record for extreme weather events that cost over $1 billion, with costly floods, fires and storms occurring roughly every three weeks. In the 1980s, by comparison, the United States experienced a billion-dollar disaster only once every four months.

Climate change is increasingly imposing costs on Americans, as prices rise for weather-related insurance or certain foods. Medical costs are also going up as more people struggle with climate consequences such as extreme heat, the report said.

The assessment marks the fifth such report released by the U.S. government since 2000. It was peer-reviewed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

Atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe, a report coauthor since the second assessment, said the newest version reflects the latest in climate science and can help policymakers and companies working on emissions cuts and ways of adapting to the consequences of a warming world.

"Today, we can document the risks that we face, per degree of warming," Hayhoe told reporters on a call. "We can put a number on the extent to which climate change is fueling our record-breaking weather extremes, and we are starting to tap the interconnectivity and understand the vulnerability of our systems from socioeconomics to national security."

It was the first report produced since 2018, when the administration of then-President Donald Trump was dismantling rules meant to rein in climate-warming emissions. Trump, a Republican who denies the science of climate change, also dismissed the 2018 assessment.

Later on Tuesday President Joe Biden, a Democrat, will speak about the report, which a White House official said was the most comprehensive assessment yet on the state of climate change in the U.S. Biden will also announce more than $6 billion in funding for climate resilience projects including bolstering the power grid and reducing flood risks, the official said.

POVERTY LINE

For the first time, this year's assessment includes a chapter on economics that illustrates how costly damages are distributed unevenly across society, often amplifying existing inequalities.

Children are reporting mental-health distress due to climate anxiety. Outdoor workers suffering dehydration through extreme heat are suffering acute kidney illness after only one day of exposure to extreme temperatures, the report says.

"Families living below the poverty line often live where climatic changes are expected to be the most economically damaging, like the already-hot Southeast," the report says.

The report also said, referring to the U.S. Southeast, that slavery, segregation and housing discrimination have resulted in many Black and other minority communities living in neighborhoods exposed to environmental risks and with fewer resources to address them compared to white neighborhoods.

It was not all doom and gloom, though. With shuttered coal plants being replaced by natural gas and renewables, the country's energy-related greenhouse gas emissions fell some 12% between 2005 and 2019 - even as the economy and population both grew.

"We're pointing in the right direction, we just want to do more, faster," said Ted Schuur, a professor of ecosystem ecology at Northern Arizona University who was not involved in writing the report.

The study's findings could encourage local and state policymakers to consider ways of adapting to the coming climate disruption, such as redesigning sewer systems to better drain water from flood-prone city streets, creating cooling centers in heat-vulnerable cities or helping hospitals plan for likely increases in vector-borne diseases, as warming encourages mosquitoes and ticks to move north into new areas.

The report also discusses national security risks of climate change, as countries compete for resources needed in the energy transition. Competition with China for minerals, for example, will likely escalate tensions between the two countries in coming years.

Climate migration, meanwhile, is expected to become a high-security risk by 2030 as people living in climate-vulnerable nations seek to cross the border into the United States for safety, the report says.

The report will be translated into Spanish for the first time by early next year.

(Reporting by Timothy Gardner in Washington; Editing by Katy Daigle and Matthew Lewis)

In fight to curb climate change, a grim report shows world is struggling to get on track

SETH BORENSTEIN

November 14, 2023

The world is off track in its efforts to curb global warming in 41 of 42 important measurements and is even heading in the wrong direction in six crucial ways, a new international report calculates.

The only bright spot is that global sales of electric passenger vehicles are now on track to match what’s needed — along with many other changes — to limit future warming to just another couple tenths of a degree, according to the State of Climate Action report released Tuesday by the World Resources Institute, Climate Action Tracker, the Bezos Earth Fund and others.

On the flip side, public money spent to create more fossil fuel use is going in the wrong direction and faster than it has in the past, said study co-author Kelly Levin, science and data director at the Bezos Earth Fund.

“This is not the time for tinkering around the edges, but it’s instead the time for radical decarbonization of all sectors of the economy,” Levin said.

“We are woefully off track and we are seeing the impact of inaction unfold around the world from extensive wildfire fires in Canada, heat-related deaths across the Mediterranean, record high temperatures in South Asia and so on," she said.

Later this month, crucial international climate negotiations start in Dubai that include the first time world negotiators will do a global stocktake on how close society is to meeting its 2015 climate goals. In advance of the United Nations summit, numerous reports from experts are coming out assessing Earth’s progress or mostly the lack of it, including a United States national assessment with hundreds of indicators. Tuesday’s 42 indicators offers one of the grimmest report cards, detailing multiple failures of society.

The report looks at what’s needed in several sectors of the global economy — power, transportation, buildings, industry, finance and forestry — to fit in a world that limits warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) over pre-industrial times, the goal the world adopted at Paris in 2015. The globe has already warmed about 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) since the mid 19th century.

Six categories — the carbon intensity of global steel production, how many miles passenger cars drive, electric buses sold, loss of mangrove forests, amount of food waste and public financing of fossil fuel use — are going in the wrong direction, the report said.

“Fossil fuel consumption subsidies in particular reached an all-time high last year, over $1 trillion, driven by the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy price spikes,” said report co-author Joe Thwaites of the Natural Resources Defense Council environmental group.

Another six categories were considered “off track” but going in the right direction, which is the closest to being on track and better than the 24 measurements that are “well off track.” Those merely off track include zero-carbon electricity generation, electric vehicles as percentage of the fleet, two- and three-wheel electric vehicle sales, grazing animal meat production, reforestation and share of greenhouse gas emissions with mandatory corporate climate risk reporting requirements.

People should be worried that this report is one of ’’too little, too late,” said University of Arizona climate scientist Katharine Jacobs, who wasn’t part of the report but praised it for being so comprehensive.

“I am not shocked that at a global scale we are not meeting expectations for reducing emissions,” Jacobs said in an email. “We cannot ignore the fact that global commitments to (greenhouse gas) reductions are essentially unenforceable and that a number of major setbacks have taken a toll on our progress.”

When trying to change an economy, the key is to start with “low-hanging fruit, i.e., the sectors of the economy that are easiest to transition and give a big bang for your buck,” said Dartmouth climate scientist Justin Mankin, who isn’t part of the report. But he said the report shows “we’re really struggling to pick the low-hanging fruit.”

___

This story corrects Katharine Jacobs’ affiliation to University of Arizona, not Arizona State.

___

Read more of AP’s climate coverage at http://www.apnews.com/climate-and-environment.

___

Follow Seth Borenstein on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @borenbears

___

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

No place in the US is safe from the climate crisis, but a new report shows where it’s most severe

ELLA NILSEN, CNN

November 14, 2023

The effects of a rapidly warming climate are being felt in every corner of the US and will worsen over the next 10 years with continued fossil fuel use , according to a stark new report from federal agencies.

The Fifth National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report due roughly every five years, warned that even though planet-warming pollution in the US is slowly decreasing, it is not happening nearly fast enough to meet the nation’s targets, nor is it in line with the UN-sanctioned goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius – a threshold beyond which scientists warn life on Earth will struggle to cope.

This year’s assessment reflects the reality that Americans can increasingly see and feel climate impacts in their own communities, said Katharine Hayhoe, a distinguished climate scientist at Texas Tech University and contributor to the report.

“Climate change is affecting every aspect of our lives,” Hayhoe told CNN.

Some of the report’s sweeping conclusions remain painfully familiar: No part of the US is truly safe from climate disasters; slashing fossil fuel use is critical to limit the consequences, but we’re not doing it fast enough; and every fraction of a degree of warming leads to more intense impacts.

But there are some important new additions: Scientists can now say with more confidence when the climate crisis has made rainstorms, hurricanes and wildfires stronger or more frequent, long-term drought more severe and heat more deadly.

Rick Curtis, right, pumps water out of his basement and onto the muddy street in front of his home in Barre, Vermont, in July 2023. - Hilary Swift/The New York Times/Redux

This summer alone, the Phoenix area baked through a record 31 consecutive days above 110 degrees, a shocking heatwave that was partly responsible for more than 500 heat-related deaths in Maricopa County in 2023 – its deadliest year for heat on record.

In July, a torrential rainstorm deluged parts of Vermont in deadly floodwaters. Then in August, Maui was devastated by a fast-moving wildfire and Florida’s Gulf Coast was slammed by its second major hurricane in two years.

President Joe Biden will deliver remarks on Tuesday and is expected to unveil more than $6 billion in funding to strengthen climate resilience “by bolstering America’s electric grid, investing in water infrastructure upgrades, reducing flood risk to communities, and advancing environmental justice for all,” an administration official said.

The US needs “a transformation of the global economy on a size and scale that’s never occurred in human history” to “create a livable future for ourselves and our children,” White House senior climate adviser John Podesta told reporters.

Here are five significant takeaways from the federal government’s sweeping climate report.

It’s easier to pinpoint which disasters were made worse by climate change

The latest report contains an important advancement in what’s called “attribution science” – scientists can more definitively show how climate change is affecting extreme events, like heatwaves, droughts to hurricanes and severe rainstorms.

Climate change doesn’t cause things like hurricanes or wildfires, but it can make them more intense or more frequent.

For instance, warmer oceans and air temperatures mean hurricanes are getting stronger faster and dumping more rainfall when they slam ashore. And hotter and drier conditions from climate change can help vegetation and trees become tinderboxes, turning wildfires into megafires that spin out of control.

“Now thanks to the field of attribution, we can make specific statements,” Hayhoe said, saying attribution can help pinpoint certain areas of a city that are now more likely to flood due to the effects of climate change. “The field of attribution has advanced significantly over the last five years, and that really helps people connect the dots.”

A structure is engulfed in flames as the Highland Fire burns in Aguanga, California, on Monday, October 30. - Ethan Swope/AP

All regions are feeling climate change, but some more severely

There is no place immune from climate change, Biden administration officials and the report’s scientists emphasized, and this summer’s extreme weather was a deadly reminder.

Some states – including California, Florida, Louisiana and Texas – are facing more significant storms and extreme swings in precipitation.

Landlocked states won’t have to adapt to sea level rise, though some – including Appalachian states like Kentucky and West Virginia – have seen devastating flooding from rainstorms.

And states in the north are grappling with an increase in tick-borne diseases, less snow, and stronger rainstorms.

“There is no place that is that that is not at risk, but there are some that are more or less at risk,” Hayhoe told CNN. “That is a factor of both the increasingly frequent and severe weather and climate extremes you’re exposed to, as well as how prepared (cities and states) are.”

Climate change is exacting a massive economic toll

Climate shocks on the economy are happening more frequently, the report said, evidenced by the new record this year for the number of extreme weather disasters costing at least $1 billion. And disaster experts have spent the last year warning the US is only beginning to see the economic fallout of the climate crisis.

Climate risks are hitting the housing market in the form of skyrocketing homeowners’ insurance rates. Some insurers have pulled out of high-risk states altogether.

Stronger storms wiping out certain crops or extreme heat killing livestock can send food prices soaring. And in the Southwest, the report’s researchers found that hotter temperatures in the future could lead to a 25% loss of physical work capacity for agricultural workers from July to September.

The US is cutting planet-warming pollution, but not nearly fast enough

Unlike the world’s other top polluters – China and India – planet-warming pollution in the US is declining. But it’s not happening nearly fast enough to stabilize the planet’s warming or meet the United States’ international climate commitments, the report explains.

The country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions fell 12% between 2005 and 2019, driven in large part by the electricity sector moving away from coal and toward renewable energy and methane gas, the latter of which is still a fossil fuel that has a significant global warming effect.

The decline is good news for the climate crisis, but look at the fine print and the picture is mixed.

The report finds US planet-warming emissions “remain substantial” and would have to sharply decline by 6% annually on average to be in line with the international 1.5-degree goal. To put that cut into perspective, US emissions decreased by less than 1% per year between 2005 and 2019 – a tiny annual drop.

Workers install steel shoring where submarine cables come onshore for the Vineyard Wind project in Barnstable, Massachusetts, in October 2022.

Water – too much and not enough – is a huge problem for the US

One of the report’s biggest takeaways centers on the precarious future of water in the US, and how parts of the country are facing a future with either extreme drought and water insecurity, or more flooding and sea level rise.

Drought and less snowpack are huge threats to Southwest communities in particular. The report’s Southwest chapter, let by Arizona State University climate scientist Dave White, found the region was significantly drier from 1991 to 2020 than the three decades before.

White said that’s an ominous sign as the planet continues to warm, with significant threats to snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains and the Rockies – both of which provide crucial freshwater in the West.

White added that a lack of freshwater in the region also has significant economic and agricultural impacts, as it supports cities, farms, and Native American tribes.

“Mountains are our natural reservoirs in the region,” White told CNN. “Climate impacts on that mountain snowpack have really significant negative effects for the way our infrastructure operates. It’s just critical for us to protect those resources.”

CNN’s Donald Judd contributed to this report.

ELLA NILSEN, CNN

November 14, 2023

The effects of a rapidly warming climate are being felt in every corner of the US and will worsen over the next 10 years with continued fossil fuel use , according to a stark new report from federal agencies.

The Fifth National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report due roughly every five years, warned that even though planet-warming pollution in the US is slowly decreasing, it is not happening nearly fast enough to meet the nation’s targets, nor is it in line with the UN-sanctioned goal to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius – a threshold beyond which scientists warn life on Earth will struggle to cope.

This year’s assessment reflects the reality that Americans can increasingly see and feel climate impacts in their own communities, said Katharine Hayhoe, a distinguished climate scientist at Texas Tech University and contributor to the report.

“Climate change is affecting every aspect of our lives,” Hayhoe told CNN.

Some of the report’s sweeping conclusions remain painfully familiar: No part of the US is truly safe from climate disasters; slashing fossil fuel use is critical to limit the consequences, but we’re not doing it fast enough; and every fraction of a degree of warming leads to more intense impacts.

But there are some important new additions: Scientists can now say with more confidence when the climate crisis has made rainstorms, hurricanes and wildfires stronger or more frequent, long-term drought more severe and heat more deadly.

Rick Curtis, right, pumps water out of his basement and onto the muddy street in front of his home in Barre, Vermont, in July 2023. - Hilary Swift/The New York Times/Redux

This summer alone, the Phoenix area baked through a record 31 consecutive days above 110 degrees, a shocking heatwave that was partly responsible for more than 500 heat-related deaths in Maricopa County in 2023 – its deadliest year for heat on record.

In July, a torrential rainstorm deluged parts of Vermont in deadly floodwaters. Then in August, Maui was devastated by a fast-moving wildfire and Florida’s Gulf Coast was slammed by its second major hurricane in two years.

President Joe Biden will deliver remarks on Tuesday and is expected to unveil more than $6 billion in funding to strengthen climate resilience “by bolstering America’s electric grid, investing in water infrastructure upgrades, reducing flood risk to communities, and advancing environmental justice for all,” an administration official said.

The US needs “a transformation of the global economy on a size and scale that’s never occurred in human history” to “create a livable future for ourselves and our children,” White House senior climate adviser John Podesta told reporters.

Here are five significant takeaways from the federal government’s sweeping climate report.

It’s easier to pinpoint which disasters were made worse by climate change

The latest report contains an important advancement in what’s called “attribution science” – scientists can more definitively show how climate change is affecting extreme events, like heatwaves, droughts to hurricanes and severe rainstorms.

Climate change doesn’t cause things like hurricanes or wildfires, but it can make them more intense or more frequent.

For instance, warmer oceans and air temperatures mean hurricanes are getting stronger faster and dumping more rainfall when they slam ashore. And hotter and drier conditions from climate change can help vegetation and trees become tinderboxes, turning wildfires into megafires that spin out of control.

“Now thanks to the field of attribution, we can make specific statements,” Hayhoe said, saying attribution can help pinpoint certain areas of a city that are now more likely to flood due to the effects of climate change. “The field of attribution has advanced significantly over the last five years, and that really helps people connect the dots.”

A structure is engulfed in flames as the Highland Fire burns in Aguanga, California, on Monday, October 30. - Ethan Swope/AP

All regions are feeling climate change, but some more severely

There is no place immune from climate change, Biden administration officials and the report’s scientists emphasized, and this summer’s extreme weather was a deadly reminder.

Some states – including California, Florida, Louisiana and Texas – are facing more significant storms and extreme swings in precipitation.

Landlocked states won’t have to adapt to sea level rise, though some – including Appalachian states like Kentucky and West Virginia – have seen devastating flooding from rainstorms.

And states in the north are grappling with an increase in tick-borne diseases, less snow, and stronger rainstorms.

“There is no place that is that that is not at risk, but there are some that are more or less at risk,” Hayhoe told CNN. “That is a factor of both the increasingly frequent and severe weather and climate extremes you’re exposed to, as well as how prepared (cities and states) are.”

Climate change is exacting a massive economic toll

Climate shocks on the economy are happening more frequently, the report said, evidenced by the new record this year for the number of extreme weather disasters costing at least $1 billion. And disaster experts have spent the last year warning the US is only beginning to see the economic fallout of the climate crisis.

Climate risks are hitting the housing market in the form of skyrocketing homeowners’ insurance rates. Some insurers have pulled out of high-risk states altogether.

Stronger storms wiping out certain crops or extreme heat killing livestock can send food prices soaring. And in the Southwest, the report’s researchers found that hotter temperatures in the future could lead to a 25% loss of physical work capacity for agricultural workers from July to September.

The US is cutting planet-warming pollution, but not nearly fast enough

Unlike the world’s other top polluters – China and India – planet-warming pollution in the US is declining. But it’s not happening nearly fast enough to stabilize the planet’s warming or meet the United States’ international climate commitments, the report explains.

The country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions fell 12% between 2005 and 2019, driven in large part by the electricity sector moving away from coal and toward renewable energy and methane gas, the latter of which is still a fossil fuel that has a significant global warming effect.

The decline is good news for the climate crisis, but look at the fine print and the picture is mixed.

The report finds US planet-warming emissions “remain substantial” and would have to sharply decline by 6% annually on average to be in line with the international 1.5-degree goal. To put that cut into perspective, US emissions decreased by less than 1% per year between 2005 and 2019 – a tiny annual drop.

Workers install steel shoring where submarine cables come onshore for the Vineyard Wind project in Barnstable, Massachusetts, in October 2022.

- M. Scott Brauer/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Water – too much and not enough – is a huge problem for the US

One of the report’s biggest takeaways centers on the precarious future of water in the US, and how parts of the country are facing a future with either extreme drought and water insecurity, or more flooding and sea level rise.

Drought and less snowpack are huge threats to Southwest communities in particular. The report’s Southwest chapter, let by Arizona State University climate scientist Dave White, found the region was significantly drier from 1991 to 2020 than the three decades before.

White said that’s an ominous sign as the planet continues to warm, with significant threats to snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains and the Rockies – both of which provide crucial freshwater in the West.

White added that a lack of freshwater in the region also has significant economic and agricultural impacts, as it supports cities, farms, and Native American tribes.

“Mountains are our natural reservoirs in the region,” White told CNN. “Climate impacts on that mountain snowpack have really significant negative effects for the way our infrastructure operates. It’s just critical for us to protect those resources.”

CNN’s Donald Judd contributed to this report.

STEPHANIE EBBS, JULIA JACOBO, KELLY LIVINGSTON, DANIEL MANZO and DANIEL PECK

GMA

Tue, November 14, 2023

Climate change is making it harder to “maintain safe homes and healthy families” in the United States, according to an extensive report compiled by experts across the federal government and released Tuesday.

The report issues a stark warning that extreme events and harmful impacts of climate change that Americans are already experiencing, such as heat waves, wildfires, and extreme rainfall, will worsen as temperatures continue to rise.

The Fifth National Climate Assessment, issued every five years, is a definitive breakdown of the latest in climate science coming from 14 different federal agencies, including NOAA, NASA, the EPA, and the National Science Foundation.

This year's report is more comprehensive than in previous because climate modeling has improved, and the authors took a more holistic look at physical and social impacts of climate change.

MORE: Earth caps off its hottest 12-month period on record, report finds

"We also have a much more comprehensive understanding of how climate change disproportionately affects those who've done the least to cause the problem," Katherine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University and co-author of the report, said in a briefing with reporters.

Some communities are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, the report says, warning that Black, Hispanic, and indigenous communities are more likely to face challenges accessing water as droughts become more intense. Climate change also creates more health risks for marginalized communities, according to the report, which says that “systemic racism and discrimination exacerbate” the impacts.

The report lays out how every part of the US is being impacted by climate change and that some areas are facing multiple worsening impacts at the same time. For example, western states saw heat waves and wildfires during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, which strained resources and added to the risk of severe illness.

In the same year, back-to-back storms during the record-breaking 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season are some examples of climate-driven compounding events that caused unprecedented demand on federal emergency response resources.

The report detailed some impacts of climate change that are being felt across the U.S., including increased risk of extreme heat and rainfall, among other weather-related events.

Other impacts cited were coastal erosion and threats to coastal communities from flooding; damage to land including wildfires and damage to forests; warming oceans and damage to ecosystems like coral reefs; risks from extreme events like fires; heatwaves and flooding, and increased inequality for minority or low-income communities.

PHOTO: Lake Mead, the country's largest man-made water reservoir, formed by Hoover Dam on the Colorado River in the Southwestern United States, has risen slowly to 47% capacity as viewed on Aug. 14, 2023 near Boulder City, Nev. (George Rose/Getty Images)

Some areas of the U.S. are also seeing more specific impacts, such as more intense droughts in the Southwest.

The assessment also notes changes in storm trends as a result of climate change. Heavy snowfall is becoming more common in the Northeast and hurricane trends are changing, with increases in North Atlantic hurricane activity and the intensification of tropical cyclones.

MORE: Increasingly warming planet jeopardizes human health, major report warns

2023 was a record setting year for billion-dollar climate disasters in the United States, officials noted in a White House briefing last week.

PHOTO: A resident, right, observes the remains of her home after it was destroyed during the Highland Fire in Aguanga, Calif., on Oct. 31, 2023. (Ethan Swope/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The report also highlights some areas of success, saying more action has been taken across the board to reduce emissions and address climate change since the last report in 2018.

Greenhouse gas emissions generated by the U.S. have been steadily decreasing since their peak in 2007, even as the energy demand goes up -- mainly due to a vast reduction in the use of coal, according to the report.

MORE: Climate scientists warn Earth systems heading for 'dangerous instability'

Efforts to adapt to and respond to climate change need to be more "transformative," the report found. This includes reducing the use of coal, building more wind turbines and electrifying buildings and making more efforts to protect people from the impacts of climate change.

PHOTO: Scenes from the flooded Foster Farms plant on Racine St. in Corcoran, Calif., on July 18, 2023. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Individuals and government leaders should look at the report as a way to help communities across the country mitigate, adapt and become more resilient to the effects of climate change, White House Climate Adviser Ali Zaidi said.

The assessment demonstrates "both a real and profound environmental risk, but also a real and profound economic opportunity," Zaidi said. The administration has also noted that adding clean energy jobs is a top priority.

MORE: Climate change, human activity causing global water cycles to become 'increasingly erratic': World Meteorological Organization

Tue, November 14, 2023

Climate change is making it harder to “maintain safe homes and healthy families” in the United States, according to an extensive report compiled by experts across the federal government and released Tuesday.

The report issues a stark warning that extreme events and harmful impacts of climate change that Americans are already experiencing, such as heat waves, wildfires, and extreme rainfall, will worsen as temperatures continue to rise.

The Fifth National Climate Assessment, issued every five years, is a definitive breakdown of the latest in climate science coming from 14 different federal agencies, including NOAA, NASA, the EPA, and the National Science Foundation.

This year's report is more comprehensive than in previous because climate modeling has improved, and the authors took a more holistic look at physical and social impacts of climate change.

MORE: Earth caps off its hottest 12-month period on record, report finds

"We also have a much more comprehensive understanding of how climate change disproportionately affects those who've done the least to cause the problem," Katherine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University and co-author of the report, said in a briefing with reporters.

Some communities are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, the report says, warning that Black, Hispanic, and indigenous communities are more likely to face challenges accessing water as droughts become more intense. Climate change also creates more health risks for marginalized communities, according to the report, which says that “systemic racism and discrimination exacerbate” the impacts.

The report lays out how every part of the US is being impacted by climate change and that some areas are facing multiple worsening impacts at the same time. For example, western states saw heat waves and wildfires during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, which strained resources and added to the risk of severe illness.

In the same year, back-to-back storms during the record-breaking 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season are some examples of climate-driven compounding events that caused unprecedented demand on federal emergency response resources.

The report detailed some impacts of climate change that are being felt across the U.S., including increased risk of extreme heat and rainfall, among other weather-related events.

Other impacts cited were coastal erosion and threats to coastal communities from flooding; damage to land including wildfires and damage to forests; warming oceans and damage to ecosystems like coral reefs; risks from extreme events like fires; heatwaves and flooding, and increased inequality for minority or low-income communities.

PHOTO: Lake Mead, the country's largest man-made water reservoir, formed by Hoover Dam on the Colorado River in the Southwestern United States, has risen slowly to 47% capacity as viewed on Aug. 14, 2023 near Boulder City, Nev. (George Rose/Getty Images)

Some areas of the U.S. are also seeing more specific impacts, such as more intense droughts in the Southwest.

The assessment also notes changes in storm trends as a result of climate change. Heavy snowfall is becoming more common in the Northeast and hurricane trends are changing, with increases in North Atlantic hurricane activity and the intensification of tropical cyclones.

MORE: Increasingly warming planet jeopardizes human health, major report warns

2023 was a record setting year for billion-dollar climate disasters in the United States, officials noted in a White House briefing last week.

PHOTO: A resident, right, observes the remains of her home after it was destroyed during the Highland Fire in Aguanga, Calif., on Oct. 31, 2023. (Ethan Swope/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The report also highlights some areas of success, saying more action has been taken across the board to reduce emissions and address climate change since the last report in 2018.

Greenhouse gas emissions generated by the U.S. have been steadily decreasing since their peak in 2007, even as the energy demand goes up -- mainly due to a vast reduction in the use of coal, according to the report.

MORE: Climate scientists warn Earth systems heading for 'dangerous instability'

Efforts to adapt to and respond to climate change need to be more "transformative," the report found. This includes reducing the use of coal, building more wind turbines and electrifying buildings and making more efforts to protect people from the impacts of climate change.

PHOTO: Scenes from the flooded Foster Farms plant on Racine St. in Corcoran, Calif., on July 18, 2023. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Individuals and government leaders should look at the report as a way to help communities across the country mitigate, adapt and become more resilient to the effects of climate change, White House Climate Adviser Ali Zaidi said.

The assessment demonstrates "both a real and profound environmental risk, but also a real and profound economic opportunity," Zaidi said. The administration has also noted that adding clean energy jobs is a top priority.

MORE: Climate change, human activity causing global water cycles to become 'increasingly erratic': World Meteorological Organization

PHOTO: A plane drops fire retardant during the Highland Fire in Aguanga, Calif., on Oct. 31, 2023. (Ethan Swope/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The last time the National Climate Assessment was released, then-President Donald Trump said he did not believe the findings.

The 2018 report found that climate change could lead to massive economic loss, especially by vulnerable communities.

Effects of climate change worsening in every part of the US, report says originally appeared on abcnews.go.com

'Every sector of human and natural society': Federal report details climate change's impact

Dinah Voyles Pulver and Doyle Rice, USA TODAY

Tue, November 14, 2023

Climate change is here and prompting unprecedented actions in every state to curb the greenhouse gas emissions fueling warming temperatures, but a new federal report out Tuesday says bigger, bolder steps are needed.

After several years of work by more than 500 authors from every state, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Guam, the White House released the massive Fifth National Climate Assessment. President Joe Biden is expected to announce more than $6 billion to bolster the electric grid, update water infrastructure, reduce flooding, and advance environmental justice.

The assessment includes more evidence than ever before to demonstrate the cause and effects of the changing climate, said L. Ruby Leung, one of its authors.

"It’s important for us to recognize that how much climate change we will be experiencing in the future depends on the choices that we make now," said Leung, a climate scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and lead author on the earth sciences chapter.

All of the impacts people are feeling, like sea level rise and extreme weather events, she said "are tied to the global warming level, to how warm the earth becomes," Leung said. "And that depends very much on the level of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere."

What is the National Climate Assessment?

The massive assessment describes the climate and economic impacts Americans will see if further action is not taken to address climate change. The report, issued roughly every four years, was mandated by Congress in the late 1980s and is meant as a reference for the president, Congress, and the public.

"Too many people still think of climate change as an issue that's distanced from us in space or time or relevance," said Katharine Hayhoe, an author of the report and chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy.

The assessment “clearly explains how climate change is affecting us here in the places where we live, both now and in the future and across every sector of human and natural society,” Hayhoe said. It also shows that "the risks matter and so do our choices."

Climate Nexus, a non-profit communications organization, said the new report is "essential reading," because it highlights the seriousness of current impacts and shows the existing pace of adaptation isn't enough to keep pace with future changes in climate.

"Without deeper cuts in global net greenhouse gas emissions and accelerated adaptation efforts, severe climate risks to the United States will continue to grow," the report states. "Each additional increment of warming is expected to lead to more damage and greater economic losses."

However, greater reductions in carbon emissions could reduce the risks and impacts, and have immediate health and economic benefits, the report states.

The impacts of climate change are felt in every corner of the country, the latest National Climate Assessment finds

What are the effects of climate change?

Millions are experiencing more extreme heat waves, with warmer temperatures and longer-lasting heat waves, the report states. It adds changes in climate are apparent in every region of the country.

Among the noted effects:

The number of nights with minimum low temperatures at or above 70 degrees has increased compared to 1901-1960 in every corner of the country except the northern Great Plains and Alaska.

Average annual precipitation is increasing in most regions, except the Northwest, Southwest, and Hawaii.

Heavier precipitation events are increasing everywhere except Hawaii and the Caribbean.

Relative sea levels are increasing along much of the coast, with the exception of Oregon, Washington, and Alaska.

In the 1980s, the country experienced on average a $1 billion disaster every four months, but now experiences one every three weeks. This year, the country has set a new record with 25 billion-dollar disasters.

Fishers and the warming climate Climb aboard four fishing boats with us to see how America's warming waters are changing

Climate scientists around the world say 2023 is almost certain to be the globe's warmest year in recorded human history. The global mean temperature through October was 1.4 Celsius (more than 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) above the pre-industrial average.

So far this year, the nation is experiencing its 11th warmest year on record through October, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. However, 12 states are experiencing their warmest or second warmest year on record.

Growing evidence that humans are changing the climate

This assessment is most notable for the certainty scientists have gained about warming and its impacts, said Leung, who served as the lead author for the report’s Earth Systems Processes chapter, which lays the scientific groundwork and is used to illustrate points throughout the report.

The chapter, a collaboration among more than a dozen authors, was intended to answer such questions as whether humans are causing global warming, whether warming is changing extreme weather and climate events and how much warming the planet might expect to see.

In prior reports, scientists often hedged their statements, for example saying they were 90% sure humans were responsible for the changes being seen," Leung said. “In this NCA 5 report, we are now saying that we are totally sure."

Starting from the 1900s, the observed warming has been caused by human activities, she said. "It’s definitive.”

Another key difference is scientists reduced by 50% the uncertainty in how much temperatures would warm if the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere doubles, she said. In previous assessments that number had hovered around a range from 2.7 degrees to 8 degrees. “It was a pretty big range,” she said. “Our goal has always been to narrow this down.”

Thanks to the increase in instrumental observations, satellite data, the study of the paleoclimate, and higher resolution computer modeling, scientists now have amassed more evidence than ever before, giving them more certainty, she said. “Now we can say that the global warming that is caused by a doubling of the CO2 in the atmosphere should be between 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit and 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit.”

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Efforts to adapt to climate change, reduce net greenhouse gas emissions, and be more energy efficient are underway in every US region and have expanded since 2018, the report concludes.

Greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. fell 12% between 2005 and 2019, mostly driven by changes in the way electricity is produced, the assessment concluded. The nation burns less coal, but more natural gas, which is cleaner. Because of the electrical industry's 40% reduction in emissions, the transportation sector took the lead as the industry with the most emissions.

Growth in the capacity of wind, solar, and battery storage is supported by the falling costs of those technologies, and that ultimately means even more emissions reductions, the report states. For example, wind and solar energy costs have dropped 70% and 90%, respectively.

While the options for cleaner technologies and lower energy use have expanded, the authors found they aren't happening fast enough for the nation to meet the goal of achieving a carbon-neutral energy system.

Without deeper cuts in global net greenhouse gas emissions and accelerated adaptation efforts, the scientists found severe climate risks to the United States will continue to grow. Each additional increment of warming is expected to lead to more damage and greater economic losses compared to previous increments of warming, and the risks of catastrophic consequences also increase.

But the report also finds that reducing greenhouse gas emissions and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere can limit future warming and associated increases in many risks, and bring immediate health and economic benefits.

What others are saying about the report:

The scientific assessment is "the latest in a series of alarm bells and illustrates that the changes we’re living through are unprecedented in human history," said Kristina Dahl, a principal climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists and a contributor to the report. "The science is irrefutable: we must swiftly reduce heat-trapping emissions and enact transformational climate adaptation policies in every region of the country to limit the stampede of devastating events and the toll each one takes on our lives and the economy."

The report illustrates three things, said Arati Prabhakar, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

The events Americans have already experienced firsthand are "unfolding as predicted."the Communities in every state and territory have taken action, People across the nation can use the assessment to take future actions.

For example, Prabhakar said the report could be used by a water utility manager in Chicago trying to understand extreme rainfall, an urban planner deciding where to locate cooling centers in Texas, or a manager of a Southeastern hospital trying to get ahead of the diseases ticks and mosquitoes are bringing into their region as a result of the changing climate.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: National Climate Assessment 2023: More action needed despite strides

Add another heat record to the pile: Earth is historically and alarmingly hot. Now what?

Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY

Updated Mon, November 13, 2023

Global average temperatures reached new highs over the past 10-12 months, notching new records in the steady march of a warming climate, two national groups announced last week.

It's been warmer than at any time in recorded history and was likely warmer than any other time in 125,000 years, an analysis by Climate Central concluded. The Copernicus Climate Change said it's also "virtually certain" that 2023 will be the hottest year in recorded history.

If these and other announcements detailed below sound familiar, it’s because heat-related records are being set and broken, over and over again, month after month and year after year in cities, states and countries around the world.

None of this should be surprising, said Andrew Pershing, vice president for science at Climate Central, a nonprofit that reports climate change news. “We should expect to set records because we live on a warming planet. We have too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.”

Heat – and cold – records have been set since people first started keeping track of temperatures, but today warm records occur far more often than cold records, and in dizzying variety. Individually they're not always attention-grabbing, but considered en masse, they present a piercing look at how steadily rising temperatures affect how we live, work and play.

All of the warming is “in line with earlier predictions,” says Michael Mann, author of the new book “Our Fragile Moment” and a professor of Earth and environmental science at the University of Pennsylvania. “Some of the impacts however, such as extreme weather events, are exceeding the predictions."

As exceptionally warm weather moves into the upper Midwest, a pedestrian walks at sunset in Oconomowoc, Wis., Tuesday, Aug. 22, 2023.

Climate Central issues report

The global average temperature for November 2022 to October 2023 was 1.32 degrees Celsius above a preindustrial baseline, Climate Central reported last week, using a method it calls the Climate Shift Index to calculate the days of above-average temperatures that can be linked to climate change.

Here's what Climate Central says its findings mean for people:

◾ Over the 12 months, 7.3 billion people, 90% of the world's population, experienced at least 10 days of temperatures strongly affected by climate change.

◾ 5.8 billion people were exposed to more than 30 days of temperatures made more likely by climate change.

◾ An estimated 1.9 billion people experienced at least one five-day heat wave over the 12 months.

Warmest October on record

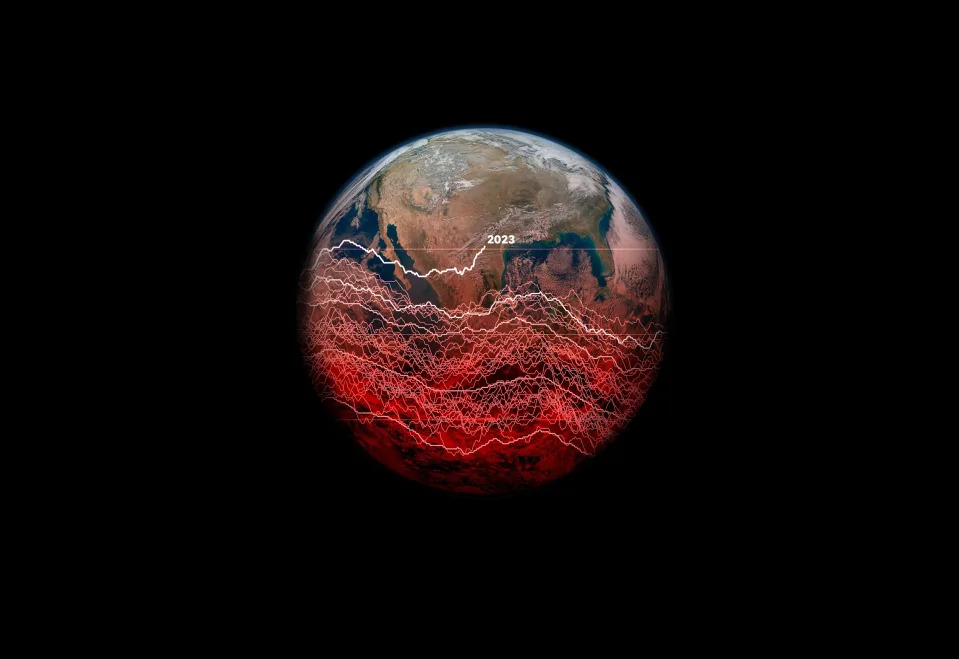

Average anomalies in global surface temperatures since 1980.

Copernicus, a weather and climate service for the European Union, also announced:

◾ October was the warmest October on record.

◾ The global temperature was the second highest of all months, behind September 2023.

◾ Year to date, the global mean temperature is the highest on record, 1.43 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial measure.

Visualizing the changing climate Global warming's impact on Earth explored

2023 one of the top two warmest so far in 10 states

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced new records this week:

◾ Four southern states – Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas – are seeing their warmest year on record.

◾ Six other states – Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York and Rhode Island – have seen their second warmest year to date.

◾ Burlington, Vermont, set a record high temperature for October after reaching 86 degrees on Oct. 4.

◾ The nation has seen a record 25 billion-dollar weather-related disasters in 2023.

Billion-dollar weather and climate related disasters in the U.S. in 2023.

Your life in data: Explore our comprehensive weather tracker that provides detailed county-level monthly precipitation and temperatures.

Other climate milestones this year, in descending order:

Oct. 16: September was the fourth month in a row of record-warm global temperatures, said Sara Kapnick, NOAA's chief scientist. The global surface temperature of 61.9 degrees was more than 2.5 degrees above the 20th-century average for September. NOAA reported it was the highest monthly global temperature anomaly of any month on record and the 535th consecutive month with temperatures above the 20th-century average.

Oct. 8: National Snow and Ice Data Center announces Antarctic sea ice reached a record wintertime low.

Sept. 14: NASA and NOAA announce Earth sweltered under its hottest summer on record.

Sept. 6: The World Meteorological Organization and the Copernicus Climate Change Service announce Earth saw its hottest June-August on record and August was the second hottest month ever, following July 2023.

Sept. 2: Officials say meteorological summer was the warmest on record in at least 20 cities, including Miami, Houston, New Orleans, Austin, Texas, and Phoenix.

Aug. 14: NOAA announces it was the warmest July globally in 174 years, "warmer than anything we'd ever seen," and probably the warmest month in history since at least 1850.

July 24: Water temperature at a buoy in a closed-in bay south of Miami reached 101.1 degrees after the city's head index topped 100 degrees for 43 consecutive days.

July 18: Phoenix endured 19 straight days of temperatures of 110 degrees or higher, breaking a record set in 1974. The summer 2023 streak kept going and lasted a full month.

July 3 - 6: Earth sets a new global daily heat record four days in a row, reaching a new high of 63 degrees on July 6.

June: Roughly 40% of the world's oceans experience marine heat waves, the most since satellite tracking began in 1991, NOAA reports.

May: Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere reached a record high, averaging 424 parts per million, according to scientists with NOAA and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. That's 51% higher than preindustrial levels and was the fourth-largest annual increase on record. NOAA reports the first four months of the year ranked record warmest in eight states along the Atlantic coast.

January: NOAA reports 18 billion-dollar disasters in 2022. It's the third highest, behind 2020 and 2021, since the agency started tracking the number. It was the third warmest year in the 128-year record and ocean heat reached a new record high.

Climate tracking: Following the changes in climate over time.

Is it too late to do anything about global warming?

No, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Record-breaking events will continue until carbon emissions are reduced to zero, said Mann and scientists with Climate Central. But the extreme weather events should stop getting worse once the surface warming stops, they said.

"The really good news is, if we stop burning fossil fuels, temperatures will stop rising," said Friederike Otto, a co-lead of World Weather Attribution, a group of scientists studying the footprint of climate change in world weather events. "And that has also immediate consequences for a lot of extreme weather events. But of course, as long as we keep burning fossil fuels they will keep rising, and extreme events are going to get worse.

“There is both urgency and agency," Mann said. "It is not too late to prevent truly catastrophic climate impacts.”

What will historians of the future say about 2023?

This year may be considered a cold year in a few years, Pershing said. "This is, this is as easy as it gets right? It's only going to get harder from here."

Otto said she hopes they'll be able to say it was "the year when it got finally so bad that people stopped playing culture wars and pretending that climate policy is a luxury topic." People should care about climate change not because they love polar bears, she said, but because "it's a massive violation of basic human rights."

Contributing: Doyle Rice, USA TODAY.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Will 2023 be Earth's hottest year? Climate change fuels heat records.

Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY

Updated Mon, November 13, 2023

Global average temperatures reached new highs over the past 10-12 months, notching new records in the steady march of a warming climate, two national groups announced last week.

It's been warmer than at any time in recorded history and was likely warmer than any other time in 125,000 years, an analysis by Climate Central concluded. The Copernicus Climate Change said it's also "virtually certain" that 2023 will be the hottest year in recorded history.

If these and other announcements detailed below sound familiar, it’s because heat-related records are being set and broken, over and over again, month after month and year after year in cities, states and countries around the world.

None of this should be surprising, said Andrew Pershing, vice president for science at Climate Central, a nonprofit that reports climate change news. “We should expect to set records because we live on a warming planet. We have too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.”

Heat – and cold – records have been set since people first started keeping track of temperatures, but today warm records occur far more often than cold records, and in dizzying variety. Individually they're not always attention-grabbing, but considered en masse, they present a piercing look at how steadily rising temperatures affect how we live, work and play.

All of the warming is “in line with earlier predictions,” says Michael Mann, author of the new book “Our Fragile Moment” and a professor of Earth and environmental science at the University of Pennsylvania. “Some of the impacts however, such as extreme weather events, are exceeding the predictions."

As exceptionally warm weather moves into the upper Midwest, a pedestrian walks at sunset in Oconomowoc, Wis., Tuesday, Aug. 22, 2023.

Climate Central issues report

The global average temperature for November 2022 to October 2023 was 1.32 degrees Celsius above a preindustrial baseline, Climate Central reported last week, using a method it calls the Climate Shift Index to calculate the days of above-average temperatures that can be linked to climate change.

Here's what Climate Central says its findings mean for people:

◾ Over the 12 months, 7.3 billion people, 90% of the world's population, experienced at least 10 days of temperatures strongly affected by climate change.

◾ 5.8 billion people were exposed to more than 30 days of temperatures made more likely by climate change.

◾ An estimated 1.9 billion people experienced at least one five-day heat wave over the 12 months.

Warmest October on record

Average anomalies in global surface temperatures since 1980.

Copernicus, a weather and climate service for the European Union, also announced:

◾ October was the warmest October on record.

◾ The global temperature was the second highest of all months, behind September 2023.

◾ Year to date, the global mean temperature is the highest on record, 1.43 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial measure.

Visualizing the changing climate Global warming's impact on Earth explored

2023 one of the top two warmest so far in 10 states

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced new records this week:

◾ Four southern states – Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas – are seeing their warmest year on record.

◾ Six other states – Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York and Rhode Island – have seen their second warmest year to date.

◾ Burlington, Vermont, set a record high temperature for October after reaching 86 degrees on Oct. 4.

◾ The nation has seen a record 25 billion-dollar weather-related disasters in 2023.

Billion-dollar weather and climate related disasters in the U.S. in 2023.

Your life in data: Explore our comprehensive weather tracker that provides detailed county-level monthly precipitation and temperatures.

Other climate milestones this year, in descending order:

Oct. 16: September was the fourth month in a row of record-warm global temperatures, said Sara Kapnick, NOAA's chief scientist. The global surface temperature of 61.9 degrees was more than 2.5 degrees above the 20th-century average for September. NOAA reported it was the highest monthly global temperature anomaly of any month on record and the 535th consecutive month with temperatures above the 20th-century average.

Oct. 8: National Snow and Ice Data Center announces Antarctic sea ice reached a record wintertime low.

Sept. 14: NASA and NOAA announce Earth sweltered under its hottest summer on record.

Sept. 6: The World Meteorological Organization and the Copernicus Climate Change Service announce Earth saw its hottest June-August on record and August was the second hottest month ever, following July 2023.

Sept. 2: Officials say meteorological summer was the warmest on record in at least 20 cities, including Miami, Houston, New Orleans, Austin, Texas, and Phoenix.

Aug. 14: NOAA announces it was the warmest July globally in 174 years, "warmer than anything we'd ever seen," and probably the warmest month in history since at least 1850.

July 24: Water temperature at a buoy in a closed-in bay south of Miami reached 101.1 degrees after the city's head index topped 100 degrees for 43 consecutive days.

July 18: Phoenix endured 19 straight days of temperatures of 110 degrees or higher, breaking a record set in 1974. The summer 2023 streak kept going and lasted a full month.

July 3 - 6: Earth sets a new global daily heat record four days in a row, reaching a new high of 63 degrees on July 6.

June: Roughly 40% of the world's oceans experience marine heat waves, the most since satellite tracking began in 1991, NOAA reports.

May: Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere reached a record high, averaging 424 parts per million, according to scientists with NOAA and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. That's 51% higher than preindustrial levels and was the fourth-largest annual increase on record. NOAA reports the first four months of the year ranked record warmest in eight states along the Atlantic coast.

January: NOAA reports 18 billion-dollar disasters in 2022. It's the third highest, behind 2020 and 2021, since the agency started tracking the number. It was the third warmest year in the 128-year record and ocean heat reached a new record high.

Climate tracking: Following the changes in climate over time.

Is it too late to do anything about global warming?

No, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Record-breaking events will continue until carbon emissions are reduced to zero, said Mann and scientists with Climate Central. But the extreme weather events should stop getting worse once the surface warming stops, they said.

"The really good news is, if we stop burning fossil fuels, temperatures will stop rising," said Friederike Otto, a co-lead of World Weather Attribution, a group of scientists studying the footprint of climate change in world weather events. "And that has also immediate consequences for a lot of extreme weather events. But of course, as long as we keep burning fossil fuels they will keep rising, and extreme events are going to get worse.

“There is both urgency and agency," Mann said. "It is not too late to prevent truly catastrophic climate impacts.”

What will historians of the future say about 2023?

This year may be considered a cold year in a few years, Pershing said. "This is, this is as easy as it gets right? It's only going to get harder from here."

Otto said she hopes they'll be able to say it was "the year when it got finally so bad that people stopped playing culture wars and pretending that climate policy is a luxury topic." People should care about climate change not because they love polar bears, she said, but because "it's a massive violation of basic human rights."

Contributing: Doyle Rice, USA TODAY.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Will 2023 be Earth's hottest year? Climate change fuels heat records.

No comments:

Post a Comment