Updated Wed, December 13, 2023

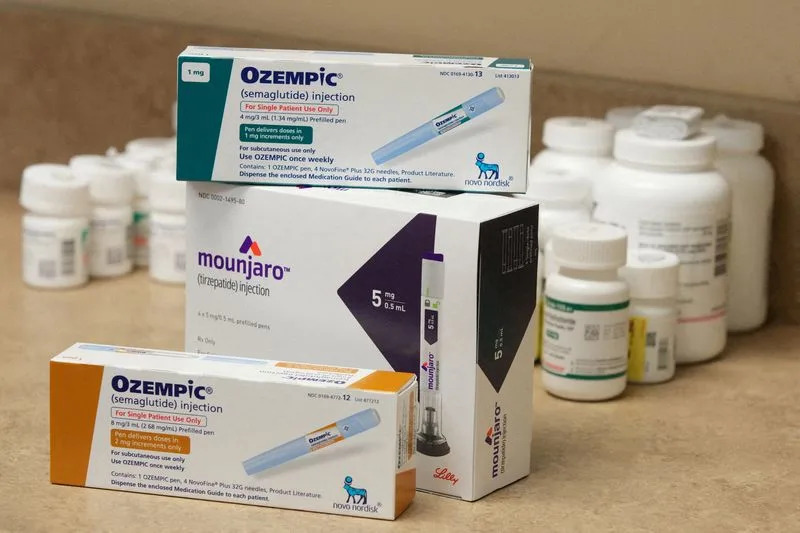

Ozempic is displayed in a pharmacy in Provo

By Deena Beasley

(Reuters) - Some patients with type 2 diabetes say they are having more difficulty getting reimbursed for drugs like Ozempic as U.S. insurers implement restrictions designed to deter doctors from prescribing the medication for weight loss.

Novo Nordisk confirmed in a recent email that it is seeing tighter health plan management of GLP-1 drugs including Ozempic and is working to minimize disruption for type 2 diabetes patients. The trend has contributed to a recent dip in U.S. prescriptions, an executive at the Danish drugmaker said at an investor conference last month. Out of 24 diabetes patients contacted by Reuters on Reddit, 13 reported recent problems getting their health plans to cover Ozempic or Mounjaro, a similar drug sold by Eli Lilly.

Elizabeth Beddow in Texas said her Blue Cross Blue Shield plan required two other drugs be tried before it would pay for Mounjaro, which her doctor prescribed after a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Instead, she was prescribed Ozempic in March, which caused extreme fatigue and gastrointestinal issues.

In September, Beddow, 57, was switched to an older drug, Lilly's Trulicity, but said her blood sugar levels are still rising. Having to start a low dose before moving up to a maximum dose with two different medications was "really hard on my body," she said. "Ironically, my insurance covers Mounjaro without step therapy on January 1." U.S. regulators approved Ozempic for diabetes in 2017 and Mounjaro in 2022. The drugs, more recently sold under the brand names Wegovy and Zepbound for weight loss, are designed to mimic a hormone called GLP-1 to regulate blood sugar, slow digestion and suppress appetite.

Most U.S. health plans cover GLP-1s for type 2 diabetes, which if uncontrolled can lead to serious complications, including kidney failure and limb amputations.

Sales of the self-injected medications, which have U.S. list prices of over $1,000 a month, quickly soared into the billions, making the companies among the world's most valuable. Sales have been limited in large part only by manufacturing capacity.

"What's really resulted in kind of a more heightened focus on prior authorization for the diabetes GLP-1 drugs is the increased volume from off-label prescribing for weight loss," said Cody Midlam, director in Willis Towers Watson's pharmacy practice, which advise employers on benefits.

Health insurers Aetna, UnitedHealth and Cigna did not respond to requests for comment.

PRIOR AUTHORIZATION ROADBLOCK

Some diabetes patients told Reuters that prior authorization, in which doctors need insurer permission before prescribing a medicine, had delayed by weeks, or even months, their ability to start a new medication or stay on a drug they had been taking. Others said insurers required them to try other drugs before their doctors were allowed to prescribe a newer medication.

A recent JP Morgan survey of U.S. benefits executives found that 74% of large employer-based health plans required diabetes patients to get prior authorization for a GLP-1, and a third of the rest planned to add the requirement as they grapple with higher spending on the medications as weight-loss tools.

Doctors often have to provide evidence of diagnosis and document that other medicines, such as generic metformin, were not adequate to control blood sugar or caused intolerable side effects. The average number of weekly Ozempic prescriptions rose 33% between the first and third quarters of this year, but has since dropped more than 6% to about 431,000, according to Iqvia Institute for Data Science.

Doctors and patients are bracing for changes in January, when individual health plans often set new coverage terms. "It may be that January 1, all of a sudden something that was covered is no longer," said Dr. Robert Gabbay, chief science officer at the American Diabetes Association. Cost can also be an issue, especially for patients who have high-deductible insurance plans. "Depending on the coverage, some people still find it not affordable. That is certainly a problem," Gabbay said.

Lilly, in an email, said it continues to help people with type 2 diabetes access Mounjaro, adding that some insurers may require confirmation of diagnosis or prior diabetes medication use.

"You have to get prior authorization every year ... For us physicians, a lot of our time is spent doing paperwork. It is something that we all have to do, but it is a barrier," said Dr. Anne Peters, an endocrinologist with Keck Medicine of USC in Los Angeles.

She said it is important that patients stay on a prescribed treatment, and not get switched off a drug because of insurance coverage. If the disease is controlled, she said, there is a better chance of preventing things like heart disease, which is what eventually kills most people diagnosed with diabetes.

"If it were an ideal world, you would use drugs like GLP-1s, associated with weight loss, early," Peters said.

(This story has been corrected to change the name to 'Cody Midlam' from 'Cory Midlam,' in paragraph 10)

(Reporting By Deena Beasley; editing by Caroline Humer and Bill Berkrot)

People say weight-loss drugs 'stop working' — here's what we know about the 'Ozempic plateau' and how to avoid it

Hilary Brueck

Wed, December 13, 2023

People say weight-loss drugs 'stop working' — here's what we know about the 'Ozempic plateau' and how to avoid it

Many patients report that Ozempic "stops working" at some point.

This "plateau" may be a kind of developed tolerance, called tachyphylaxis.

Some patients up their dose or switch to a stronger drug to move past the plateau.

On Ozempic — a diabetes drug widely used off-label for weight loss — people generally lose about 10% to 15% of their body weight. At least, that's what you'll hear.

The reality is that, like any medication, different bodies react to the active ingredient (semaglutide) quite differently. While some people might lose less than 5% of their body weight on Ozempic, others can surpass 20% or 25% weight loss on the hormone-mimicking shot.

Doctors and scientists are still developing their understanding of why these individual differences exist but, whatever the reason, they do. And, while some people can continue to lose weight on semaglutide until they reach a preset "goal weight," others may struggle to continue making progress on the drug after a few months of use.

This is what many doctors, as well as frustrated patients commiserating online, often call the "Ozempic plateau," though you may have heard it described as a phenomenon where "Ozempic stops working." Here's what's actually going on:

It's important to personalize dosage of weight-loss drugs

Getty Images

Ozempic, developed by Novo Nordisk as a drug to stabilize blood sugar in people with Type 2 diabetes, works on both the belly and the brain. It mimics a hormone that slows down stomach emptying, keeping people fuller longer, and tells the brain to be satisfied with less food.

But not everyone's hormones, stomachs, and brains are wired the same way. As such, people may need to reach for different dosages of the drug to feel it working. For some small portion of people (maybe one in 10 or less), Ozempic just never works at all. But most people will react to the drug in some way, if they're given the proper dosage.

"Very frequently, people — let's say on their first, second dosage — they literally feel nothing. And they start to wonder, what did my doctor give me?" Dr. Steven Batash, a gastric sleeve and weight loss specialist who uses Ozempic in his practice, told Business Insider.

If those initial dosages don't have an effect, a doctor may recommend increasing the dosage again, going up to one milligram.

Suddenly at the proper dose, the patient may go hours and hours between meals, feeling fuller quicker, and satisfied for longer periods of time, Batash explains. "Oh yes, I now feel it!" he says, mimicking the reaction of a hypothetical patient.

Patients may also start to feel more side effects after increasing their dose, like nausea or the occasional vomiting, but this is also a sign the drug is working — at least in the short-term.

Patients may need to up their dose

Some patients find out that the drug becomes less effective for them over time.Getty Images

One way a "plateau" can set in is after several weeks or months of such an effective dosage, according to Batash.

The doctor says this is when some patients discover that "this dosage that used to really do its magic is no longer doing the trick. And I'm starting to revert to my old bad habits, and I find that the hunger suppression is not as effective."

Sometimes, this kind of habituation to a drug — a phenomenon called tachyphylaxis — can be easily solved by upping the person's dose.

But in some cases, patients have already maxed out their dose. For others, upping their prescription does not undo the plateau.

Here, biology and pharmacy have hit their limits, for reasons doctors like Batash still don't quite grasp.

"We can only hypothesize why it doesn't work," Batash said. "It could be that a person's baseline emptying of food is so delayed that you're not going to get an incremental delay from this medication, or the brain has more than one satiety center in the brain, and perhaps the specific satiety center in the brain that Ozempic works on in this particular person may not be super sensitive."

Changing to other, stronger weight-loss drugs may help boost people past their plateaus

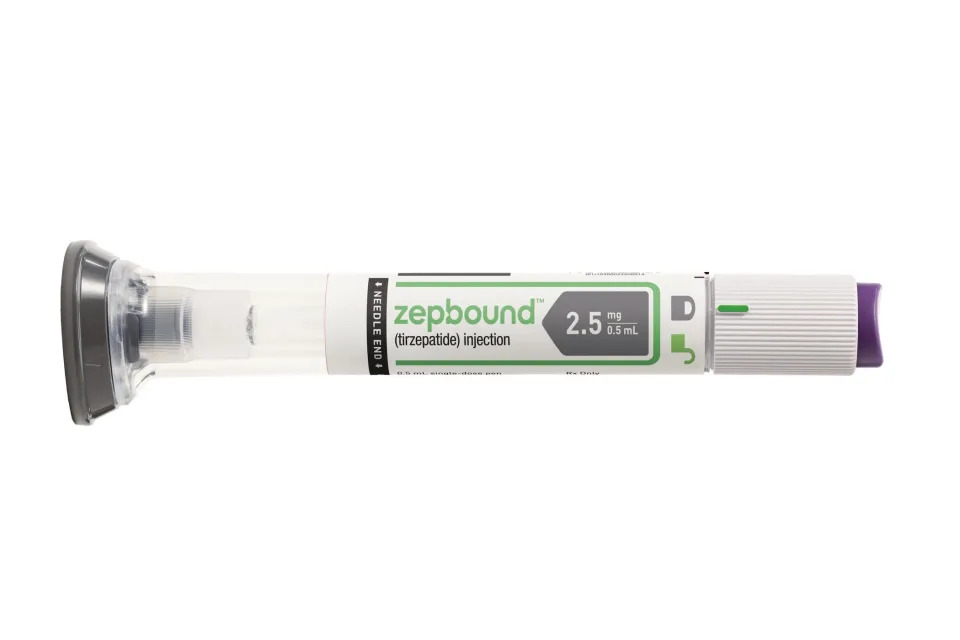

Zepbound is the new weight loss injection from Eli Lilly. It's the same drug that's in Mounjaro for Type 2 diabetes (tirzepatide.)Eli Lilly

Newer, stronger weight-loss drugs are coming to market, which boost multiple hunger hormones, instead of just one. It's possible that someone who doesn't respond strongly to Ozempic, or who plateaus in their weight loss, may feel more of an effect on their body by injecting multiple hormones at once with one of these stronger drugs.

Tirzepatide, for example, is a double agonist, which mimics two hunger hormones. It's marketed as Mounjaro for diabetes and Zepbound for obesity, and people generally lose more weight with it than with semaglutide. Then, there are the yet-to-come "king kong" triple agonist drugs, which are still in clinical trials, but which appear to help people lose on average upwards of 25% of their body weight, rivaling bariatric surgery.

But, no drug is perfect.

"Pretty much all weight loss therapies that have been studied seem to have some kind of plateau," Dr. Sajad Zalzala, chief medical officer at the telemedicine website AgelessRx, said. He believes the limitations of these hormonal drugs just underscore how much we have to learn when it comes to understanding all the complex forces regulating weight and metabolism.

"It highlights the fact that there's nothing miraculous about semaglutide at the end of the day," he said. "I think that's just kind of physiology, that your body's only willing to go so far to shed the weight."

Dr. Peter Billing, who runs a network of Transform Weight Loss centers in the greater Seattle area, says many of his patients will lose around 10 pounds a month on Ozempic, regardless of their size.

"Even someone who needs to lose 30 pounds, they'll lose 10 pounds a month and then they won't lose too much," Billing told Insider. "It just stops. It plateaus."

Many patients with diabetes quit Ozempic, Mounjaro within a year

Ernie Mundell, HealthDay News

Tue, December 12, 2023

A new study found half of patients who use a new class of injected drugs that includes blockbusters like Ozempic (semaglutide) and Mounjaro (tirzepatide) quit them within a year.

Photo by Tesa Photography/Pixabay

Many Americans battling diabetes are turning to a new class of injected drugs that includes blockbusters like Ozempic (semaglutide) and Mounjaro (tirzepatide).

But a new study finds half of patients who use these "second line" therapies -- a class called GLP-1 RAs -- quit them within a year.

The main factor: Gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, according to the researchers.

"Discontinuation is bad. It is common in all five types of [diabetes] medications, but we see significantly more in those prescribed the GLP-1 RAs," said study lead author David Liss. He's a research associate professor of general internal medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

The study was published Tuesday in the American Journal of Managed Care.

People newly diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes are typically first given a standby medication, metformin, to help manage their blood sugar.

But sometimes metformin isn't enough, and patients then migrate to a second-line therapy, such as a GLP-1 RA.

Besides Mounjaro and Ozempic, this class includes exenatide (Byetta), liraglutide (Saxenda) or dulaglutide (Trulicity).

In the new study, Liss' group tracked prescription adherence for more than 82,000 diabetes patients tracked between 2014 and 2017.

They looked at people taking one of five classes of diabetes meds (excluding insulin). In four of the five classes, about 38% of people stopped taking the drug within a year of switching away from metformin, the study found.

However, that number rose to 50% among those who'd been switched to a GLP-1 RA, the researchers noted.

"Presumably, the doctor is saying, 'You need to start a new medication to control your Type 2 diabetes,' and then within a year, half of them just stop and don't start another one, and that's not a good thing," Liss said in a Northwestern news release.

The study wasn't designed to pinpoint why folks quit the drugs, although gastrointestinal side effects probably play a role, the researchers said.

Those issues can also arise when folks without diabetes take a GLP-1 RA for weight loss.

Two newly approved GLP-1 RA medications -- Wegovy (a different form of semaglutide) and Zepbound (a different form of tirzepatide), are designed for weight loss.

"We know there are gastrointestinal side effects for these drugs that are currently in the news, both for patients with diabetes and patients attempting to lose weight," Liss said.

Quitting a GLP-1 RA med doesn't necessarily mean an immediate spike in blood sugar, "but discontinuation still puts these patients at greater risk for downstream hospitalizations related to diabetes," Liss warned.

His team worry that many patients may stop using their GLP-1 RA without mentioning it to their physician. That's a potentially dangerous move.

"Our results may represent a 'wake-up call' for clinicians that many of their patients were not taking the medicines that were prescribed," Liss said. "While we don't know if providers were aware of the discontinuation events observed in this study, our results highlight the need for ongoing communication between patients and prescribers over time -- around medication benefits, side effects and costs -- not just at the time of prescribing."

More information

Find out more about this class of medications at the Mayo Clinic.

Copyright © 2023 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

What Is Zepbound, Ozempic’s Newest Competitor?

Many Americans battling diabetes are turning to a new class of injected drugs that includes blockbusters like Ozempic (semaglutide) and Mounjaro (tirzepatide).

But a new study finds half of patients who use these "second line" therapies -- a class called GLP-1 RAs -- quit them within a year.

The main factor: Gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, according to the researchers.

"Discontinuation is bad. It is common in all five types of [diabetes] medications, but we see significantly more in those prescribed the GLP-1 RAs," said study lead author David Liss. He's a research associate professor of general internal medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

The study was published Tuesday in the American Journal of Managed Care.

People newly diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes are typically first given a standby medication, metformin, to help manage their blood sugar.

But sometimes metformin isn't enough, and patients then migrate to a second-line therapy, such as a GLP-1 RA.

Besides Mounjaro and Ozempic, this class includes exenatide (Byetta), liraglutide (Saxenda) or dulaglutide (Trulicity).

In the new study, Liss' group tracked prescription adherence for more than 82,000 diabetes patients tracked between 2014 and 2017.

They looked at people taking one of five classes of diabetes meds (excluding insulin). In four of the five classes, about 38% of people stopped taking the drug within a year of switching away from metformin, the study found.

However, that number rose to 50% among those who'd been switched to a GLP-1 RA, the researchers noted.

"Presumably, the doctor is saying, 'You need to start a new medication to control your Type 2 diabetes,' and then within a year, half of them just stop and don't start another one, and that's not a good thing," Liss said in a Northwestern news release.

The study wasn't designed to pinpoint why folks quit the drugs, although gastrointestinal side effects probably play a role, the researchers said.

Those issues can also arise when folks without diabetes take a GLP-1 RA for weight loss.

Two newly approved GLP-1 RA medications -- Wegovy (a different form of semaglutide) and Zepbound (a different form of tirzepatide), are designed for weight loss.

"We know there are gastrointestinal side effects for these drugs that are currently in the news, both for patients with diabetes and patients attempting to lose weight," Liss said.

Quitting a GLP-1 RA med doesn't necessarily mean an immediate spike in blood sugar, "but discontinuation still puts these patients at greater risk for downstream hospitalizations related to diabetes," Liss warned.

His team worry that many patients may stop using their GLP-1 RA without mentioning it to their physician. That's a potentially dangerous move.

"Our results may represent a 'wake-up call' for clinicians that many of their patients were not taking the medicines that were prescribed," Liss said. "While we don't know if providers were aware of the discontinuation events observed in this study, our results highlight the need for ongoing communication between patients and prescribers over time -- around medication benefits, side effects and costs -- not just at the time of prescribing."

More information

Find out more about this class of medications at the Mayo Clinic.

Copyright © 2023 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

What Is Zepbound, Ozempic’s Newest Competitor?

CT Jones

Wed, December 13, 2023

ROLLING STONE

While Zepbound, the new drug from Eli Lilly, doesn’t have the name recognition of Ozempic, it still represents a changing landscape in weight loss management, one pharmaceutical companies are working to cash in on. Even with the popularity of new weight loss drugs like Ozempic, consumers say high costs and major shortages cause roadblocks to receiving care. But pharmaceutical brands say they have the answer: even more drugs.

On Nov. 8, the Food and Drug Administration approved Zepbound, making the injectable drug available as a treatment for weight loss. Also known as tirzepatide, the drug was already available as the brand-name Mounjaro, but only had FDA approval for diabetes treatment. Under its new name, Zepbound is a direct competitor of Wegovy, the weight loss drug created by Novo Nordisk.

More from Rolling Stone

Novo Nordisk Claims Ozempic Knockoffs Aren't Just Cheap - They're Dangerous

How an Obession With Self-Care Paved The Way for Ozempic

FDA Adds New Side Effect Warning to Ozempic Label

Similar to other popular weight loss drugs, including Ozempic, Rybelsus, and Wegovy, Zepbound mimics the GLP-1 hormone, a hormone in the stomach that regulates sugar levels and appetite. However, unlike semaglutide, Zepbound is a dual agonist — meaning it also mimics the body’s GIP hormone (glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide), another naturally occurring intestinal hormone that helps with insulin production. Zepbound is injected under the skin once a week, with dosages slowly increased over 20 weeks until patients reach their target dose. According to the FDA, the maximum dosage of Zepbound is 15 mg per week.

While Zepbound is making its debut in an already crowded market, it has a slight advantage in terms of use. According to the FDA, trial participants saw an average weight loss of 18 percent. (Wegovy trial patients lost an average 15 percent of their body weight, CNBC reports.) But Zepbound still includes many common side effects from GLP-1 medications, like “nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, stomach pain, burping, hair loss and gastroesophageal reflux disease,” according to the FDA.

Zepbound’s approval comes at a time of rapid growth for chronic weight loss drugs. When Ozemipc was first approved in 2017, the drug was intended solely for diabetics. But after users also reported faster weight loss, the drug and others like it quickly became a desirable option online for weight management. By 2020, Ozempic had a reputation online as a “miracle drug.” Parent company Novo Nordisk quickly released Wegovy, a drug with the same active ingredients as Ozempic, but approved by the FDA specifically for weight loss.

But the new approval wasn’t enough to curb the rising demand for the drugs. As of Sept. 2023, Ozempic and Wegovy are both under a national shortage. The lack of medication hasn’t just driven desire for the drugs — it has pushed extremely desperate patients to seek out illegal or compounded versions. In November, Novo Nordisk announced it had filed at least 12 legal complaints against companies they claimed sold drugs with FDA-banned chemicals, misleading branding, and potentially injurious components. But the warnings haven’t stopped patients from seeking out telehealth companies or compounding — leading to increased work from pharmaceutical companies to address the national shortage. The FDA approved Zepbound under the organization’s Fast Track program, which expedites the review and approval of drugs to treat serious conditions or a large “unmet” medical need. While Zepbound’s arrival could relieve some pressure from patients still waiting for Ozempic scripts, its equally high price tag (upwards of $1,000 each month) means eager clients might still take more dangerous routes to obtain their medication.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death such as heart disease, stroke and diabetes,” FDA Diabetes Division Director Dr. John Sharretts said in a statement. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

Oprah Winfrey Ends the Shaming and Confesses to Using Weight-Loss Medication Following Fans’ Speculation She’s on Ozempic

Niko Mann

ATLANTA BLACK STAR

Wed, December 13, 2023

Oprah Winfrey recently admitted to using a weight-loss medication to maintain her weight after fans speculated that the media mogul was using Ozempic, which is a popular drug often used by celebrities.

Winfrey struggled with her weight throughout the two-decade-plus run of her syndicated talk show, “The Oprah Winfrey Show” and became the butt of numerous cruel jokes by comedians on late-night television.

The former talk show host was previously slammed for shaming weight loss drugs and calling them “the easy way out.” But now she’s opening up about her weight-loss journey, and she feels “relieved” that a weight-loss drug now exists to help people lose and maintain their weight.

Oprah Winfrey opens up about using weight loss drugs following

Wed, December 13, 2023

Oprah Winfrey recently admitted to using a weight-loss medication to maintain her weight after fans speculated that the media mogul was using Ozempic, which is a popular drug often used by celebrities.

Winfrey struggled with her weight throughout the two-decade-plus run of her syndicated talk show, “The Oprah Winfrey Show” and became the butt of numerous cruel jokes by comedians on late-night television.

The former talk show host was previously slammed for shaming weight loss drugs and calling them “the easy way out.” But now she’s opening up about her weight-loss journey, and she feels “relieved” that a weight-loss drug now exists to help people lose and maintain their weight.

Oprah Winfrey opens up about using weight loss drugs following

fans’ speculation about her thinner physique.

(Photo: @oprah / Instagram)

“It was public sport to make fun of me for 25 years. I have been blamed and shamed, and I blamed and shamed myself,” Winfrey said in a interview with People magazine published this week. “I was on the cover of some magazine and it said, ‘Dumpy, Frumpy and Downright Lumpy.’ I didn’t feel angry. I felt sad. I felt hurt. I swallowed the shame. I accepted that it was my fault.”

Although Winfrey admitted to using a weight-loss drug, she did not specify which one. Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro are the three of the most popular drugs people are currently using for weight loss. Wegovy is the only one approved for weight loss while Ozempic and Mounjaro were created to treat diabetes but patients also found them effective for losing weight.

“I now use it as I feel I need it, as a tool to manage not yo-yoing,” she continued. “The fact that there’s a medically approved prescription for managing weight and staying healthier, in my lifetime, feels like relief, like redemption, like a gift, and not something to hide behind and once again be ridiculed for. I’m absolutely done with the shaming from other people and particularly myself.”

The 69-year-old’s latest weight-loss journey began after having knee surgery back in 2021 and she began hiking. She also had an “aha” moment during a taping of Oprah Daily’s “The Life You Want” series last July. Winfrey’s panel included weight loss experts and clinicians for an episode titled “The State of Weight” as she learned about weight-loss prescription drugs.

“I realized I’d been blaming myself all these years for being overweight, and I have a predisposition that no amount of willpower is going to control,” she said. “Obesity is a disease. It’s not about willpower — it’s about the brain.”

After Winfrey lost 67 pounds by starving herself on a liquid diet in 1988, she brought out a wagon of fat during an episode of “The Oprah Winfrey Show” to show viewers how much extra weight she’d been carrying on her frame.

She had weighed more than 200 pounds at the time and whittled herself down on the Optifast diet, which enabled her to get into her old size 10 in Calvin Klein jeans. Unfortunately, she gained the weight back and has continued to struggle with her weight throughout her career.

Winfrey now incorporates exercise into her routine and can hike several miles per day. She also drinks one gallon of water daily and uses a WeightWatchers-style approach of counting points. “I felt stronger, more fit and more alive than I’d felt in years,” she said of her exercise routine.

Winfrey is only a few pounds away from her goal of 160 pounds and noted that the prescription weight-loss drug isn’t a magic solution for her and stresses the importance of healthy living. “The Color Purple” producer also noted that the drug helped her to only gain a half-pound over Thanksgiving as opposed to “gaining eight pounds like I did last year.”

“It’s everything,” she said. “I know everybody thought I was on it, but I worked so damn hard. I know that if I’m not also working out and vigilant about all the other things, it doesn’t work for me.”

“It was public sport to make fun of me for 25 years. I have been blamed and shamed, and I blamed and shamed myself,” Winfrey said in a interview with People magazine published this week. “I was on the cover of some magazine and it said, ‘Dumpy, Frumpy and Downright Lumpy.’ I didn’t feel angry. I felt sad. I felt hurt. I swallowed the shame. I accepted that it was my fault.”

Although Winfrey admitted to using a weight-loss drug, she did not specify which one. Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro are the three of the most popular drugs people are currently using for weight loss. Wegovy is the only one approved for weight loss while Ozempic and Mounjaro were created to treat diabetes but patients also found them effective for losing weight.

“I now use it as I feel I need it, as a tool to manage not yo-yoing,” she continued. “The fact that there’s a medically approved prescription for managing weight and staying healthier, in my lifetime, feels like relief, like redemption, like a gift, and not something to hide behind and once again be ridiculed for. I’m absolutely done with the shaming from other people and particularly myself.”

The 69-year-old’s latest weight-loss journey began after having knee surgery back in 2021 and she began hiking. She also had an “aha” moment during a taping of Oprah Daily’s “The Life You Want” series last July. Winfrey’s panel included weight loss experts and clinicians for an episode titled “The State of Weight” as she learned about weight-loss prescription drugs.

“I realized I’d been blaming myself all these years for being overweight, and I have a predisposition that no amount of willpower is going to control,” she said. “Obesity is a disease. It’s not about willpower — it’s about the brain.”

After Winfrey lost 67 pounds by starving herself on a liquid diet in 1988, she brought out a wagon of fat during an episode of “The Oprah Winfrey Show” to show viewers how much extra weight she’d been carrying on her frame.

She had weighed more than 200 pounds at the time and whittled herself down on the Optifast diet, which enabled her to get into her old size 10 in Calvin Klein jeans. Unfortunately, she gained the weight back and has continued to struggle with her weight throughout her career.

Winfrey now incorporates exercise into her routine and can hike several miles per day. She also drinks one gallon of water daily and uses a WeightWatchers-style approach of counting points. “I felt stronger, more fit and more alive than I’d felt in years,” she said of her exercise routine.

Winfrey is only a few pounds away from her goal of 160 pounds and noted that the prescription weight-loss drug isn’t a magic solution for her and stresses the importance of healthy living. “The Color Purple” producer also noted that the drug helped her to only gain a half-pound over Thanksgiving as opposed to “gaining eight pounds like I did last year.”

“It’s everything,” she said. “I know everybody thought I was on it, but I worked so damn hard. I know that if I’m not also working out and vigilant about all the other things, it doesn’t work for me.”

Fans reacted on social media, and most didn’t seem upset that Winfrey is using a prescription drug to maintain her weight after seeing her struggle for so many years.

One fan wrote, “Oprah is on Ozempic and still found a way to push weight watcher points. She gone find some way to bring press to her businesses. She’s a true entrepreneur lol.” Another fan replied, “Were people really surprised that Oprah is on Ozempic? Oprah been trying to lose weight since I was a kid. And I’m 40!”

Winfrey has served as an ambassador for Weight Watchers since 2015. She also serves as a board member and adviser and owns 10 percent of the company.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment