Climate change is melting ice roads — a lifeline for remote Indigenous communities

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center. It was produced by Grist and co-published with IndigiNews.

It was the last night of February and a 4×4 truck vaulted down the 167-kilometre winter road to Cat Lake First Nation in northern “Ontario,” a road made entirely of ice and snow. Only the light of the stars and the red and white truck lights illuminated the dense, snow-dusted spruce trees on either side of the road. From the passenger seat, Rachel Wesley, a member of the Ojibway community and its economic development officer, told the driver to stop.

The truck halted on a snow bridge over a wide creek — one of five made of snow along this road. It was wide enough for only one truck to cross at a time; its snowy surface barely two feet above the creek. Wesley zipped up her thick jacket and jumped out into the frigid night air. She looked at the creek and pointed at its open, flowing water.

“That’s not normal,” she said, placing a cigarette between her lips.

Wesley, who wore glasses and a knit cap pulled over her shoulder-length hair, manages the crews that build the winter road — a vital supply route that the community of 650 people relies on to truck in lumber for housing, fuel, food, and bottled water. In the past, winters were so cold that she could walk on the ice that naturally formed over the creek. Now it no longer freezes, and neither do the human-made snow bridges.

“It’s directly caused by global warming,” she said, lighting the cigarette.

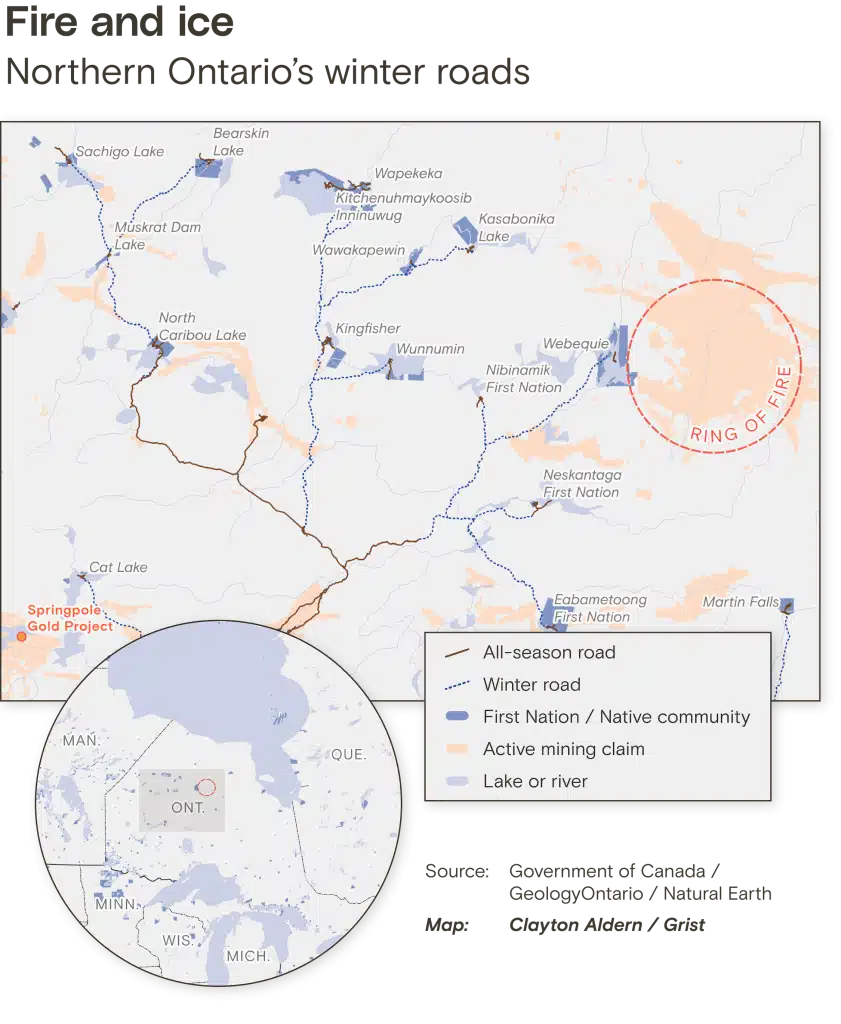

More than 50 First Nations in Canada — with 56,000 people total — depend on approximately 6,000 kilometres of winter roads. There are no paved roads connecting these Indigenous communities to the nearest cities. Most of the year, small planes are their only lifeline. But in winter, the lakes, creeks, and marshes around them freeze, allowing workers to build a vast network of ice roads for truck drivers to haul in supplies at a lower cost than flying them in.

Despite their isolation, the ice roads are community spaces. They guide hockey and broomball teams from small reserves to big cities to compete in tournaments. They enable families to stock up on cheap groceries. They bring people to medical appointments in cities and facilitate hunting and fishing trips with relatives in neighboring communities.

But the climate crisis is making it harder to build and maintain the ice roads. Winter is arriving later, pushing back construction, and spring is appearing earlier, bringing even the most robust frozen highways to an abrupt end. Less snow is falling, making the bridges smaller and more vulnerable to collapse under heavy trucks.

The rising temperatures give trucks only a few short weeks to bring in supplies — and often with half-loads due to thin lake ice and fragile snow bridges. Last year, chiefs in northern “Ontario” declared a state of emergency when the winter roads failed to freeze on time, and in March this year, rain shut down the ice roads to five communities.

First Nations urgently need permanent roads, but it’s unclear who will pay for them. Government of Canada officials say it’s not their responsibility, and with price tags running into the hundreds of millions of dollars for each community, First Nations typically don’t have the money to fund them.

But there is a third, more complex option: Many communities that rely on disappearing ice roads sit atop lucrative minerals. And where mining is approved, road permits and government funding soon follow.

The Ring of Fire and development on Indigenous lands

For nearly two decades, companies and governments have eyed a circular mining area in northern “Ontario” as a promise of economic prosperity. Named after the Johnny Cash song, the Ring of Fire spans 5,000 kilometres and contains chromite, nickel, copper, platinum, gold, and zinc, all of which can be used to make EV batteries, cell phones, and military equipment. Scattered across the north are dozens of mines that extract gold, iron, and other minerals, but none compare to the scale of the Ring of Fire.

But resistance by First Nations and a lack of paved roads has stalled extraction. Mining the region could threaten the fight against climate change: “Ontario’s” northern peatlands, for instance, sequester an estimated 35 billion tons of carbon that could be released if the land is mined. The proposed Ring of Fire mining area alone holds about 1.6 billion tonnes of carbon. To put that in perspective, the Amazon rainforest sequesters about 112 billion tonnes of carbon.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford has longed for years to develop the Ring of Fire, even promising to “hop on a bulldozer” himself. The province, which is responsible for natural resources and road permitting, has committed CAD$1 billion to build permanent roads to open up mining, asking the federal government to kick in another CAD$1 billion. Meanwhile, at least a dozen First Nations in “Ontario” are requesting government funding for all-season roads.

During the recent election, Ford vowed to “unlock” the Ring of Fire and has introduced legislation to fast-track development, actions that some First Nation leaders perceived as a threat. The Nishnawbe Aski Nation, or NAN for short, a regional Indigenous government representing 49 First Nations in northern “Ontario,” warned the province that it was overstepping its authority.

“The unilateral will of the day’s government will not dictate the speed of development on our lands, and continuing to disregard our legal rights serves to reinforce the colonial and racist approach that we have always had to fight against,” said NAN Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler in a statement. First Nations in the Ring of Fire area are not necessarily antidevelopment, but Fiddler said they must be engaged as partners under regional treaties.

Responding to the premier’s promise to get on a bulldozer, Eabametoong First Nation Chief Solomon Atlookan said, “Nobody’s gonna come without our consent.”

Located in the Ring of Fire region, Eabametoong relies on a winter road for supplies, including lumber for housing. The seasonal window for their ice road has shrunk so much that the community struggles to bring in enough materials to address a severe housing crisis. According to Atlookan, some homes have as many as 14 people living under one roof. Eabametoong used to haul fuel over the winter road, but it is now flown in at a much higher cost.

Atlookan said that building a permanent road could threaten traditional ways of life by bringing in tourists, allowing settlers more access to lands to build cottages, and increasing competition over hunting and fishing. But climate change and rising costs are forcing him to seriously consider a paved road.

“We need to begin working on it now,” he said.

Atlookan is not against mining but knows there are trade-offs. His community’s traditional territories contain countless interwoven streams, lakes, and rivers, and mining upstream could contaminate nearby walleye spawning habitat.

“They don’t realize how interconnected those tributaries are, where the fish spawn,” he said. ”It’ll destroy that livelihood for our communities. So there’s a lot at stake here.”

The province is motivated to build all-season roads to allow a more sustainable flow of goods as climate change threatens the ice roads, according to a spokesperson for Greg Rickford, “Ontario’s” minister of Indigenous affairs and First Nations economic reconciliation. They’re committed to “meaningful partnerships” to advance economic opportunities in the region, the spokesperson added.

But that’s not how Atlookan views the situation. He described a conversation he had with Rickford, who offered to build him an all-season road. He said he asked Rickford if he wanted access to minerals, and the minister denied that the road would be for mining access. “I said, ‘Rickford, that is what this is all about.’”

While Eabametoong is located in the Ring of Fire region and shares a network of winter roads with a cluster of other communities, Cat Lake is in a different situation.

Cat Lake is 257 kilometres west of Eabametoong, as the crow flies. The reserve rests at the edge of a watershed where five major rivers flow in opposite directions, affording the community access to various rivers for travel, hunting, and living off the land. It is not located in the Ring of Fire region and has its own winter road that doesn’t connect to other communities.

Cat Lake is rushing to build an all-season road by 2030 at a cost of CAD$125 million, which the community cannot afford on its own. Cat Lake is considering two routes for an all-season road. One option involves construction over the current 167-kilometre winter road. The other option is to piggyback on an all-season road that would be built to a gold mine, if it is approved. The Springpole mine site is 40 kilometres from Cat Lake, giving the community the option to build a shorter all-season road.

First Mining Gold wants to drain a lake and dig a 1.5-kilometre open-pit mine to reach the gold underneath. To access Springpole, the company needs to build an all-season road.

In past years, company vehicles reached the site by driving over a winter road that passed over a frozen lake. But several times those vehicles plunged through the thin ice due to warm weather, according to First Mining Gold’s 2023 ESG report. The company figured it was too risky to keep crossing the lake, so it asked the province for permits to build an overland winter road.

Ontario issued a permit for the company to build the winter road without Cat Lake’s consent, prompting the First Nation to request an injunction to stop construction. The community dropped its court case after reaching a settlement with the province last year. First Mining Gold did not reply when asked for comment.

In September 2020, as the company prepared to apply for permits, Wesley invited Elders to a meeting to ask two questions: Did they support Springpole, and did they want an all-season road?

“In order for us to get a road, we might have to let them open the mine,” Wesley explained.

The Elders said they don’t value gold but do value lake trout, and they believed the project would destroy fish habitat. Elders also said they wanted an all-season road that would allow young people to connect with the world while embracing their culture.

“We said ‘no’ to the mine, and we said ‘yes’ to the road,” she said.

After the Elders’ meeting, Wesley began to look for ways to fund a permanent road without relying on mining. She said the federal government is hesitant to fund an all-season road to only one community, and the province won’t talk to Cat Lake about an all-season road. To unlock funding, she began pursuing economic partnerships like working with PRT Growing Services on forest regeneration and a local bioeconomy that would involve a tree-seedling nursery in the community. Cat Lake is also partnering with Natural Resources Institute Finland to do an assessment of their forests.

“Relying on industry would mean that we would have to do mining with First Mining. And like I said, the community values land, air, and water. We don’t value gold,” she said.

‘Every year it’s been getting a little bit warmer’

The farther north you fly in “Ontario,” the fewer glimpses of infrastructure like power lines, cell towers, or paved roads. The winter landscape is composed of evergreen forests shot through with rivers and lakes, bright white from the snow resting on top. From a plane, the ice roads can be seen cutting through the trees and running over frozen lakes.

On a chilly, sunny afternoon on the Cat Lake winter road, Jonathan Williams drove a red truck with chains pulling heavy tires behind it. Known as “drags,” the tires smooth out the rough parts of the road. Warm weather makes the surface bumpy, requiring constant attention from workers like Williams, who has built winter roads for the last eight years.

“The year I started, it was minus 50 [degrees Celsius],” he said. “I was out fixing trucks on the road, and it was frickin’ crazy getting frostbite on your hands. After that, every year it’s been getting a little bit warmer, a little bit warmer.”

It costs about CAD$500,000 each year to build and maintain Cat Lake’s winter road. The warming climate is taking a toll on the machines used on the road, but the budget no longer covers the expense of a CAD$10,000 broken machine part.

Winter road construction, which splits the cost 50/50 between Indigenous Services Canada and the Ontario Ministry of Northern Development, typically starts in November or early December. That’s when crews drive heavy machines over the earth to press it down. When snow arrives, they use grooming machines to pack it.

Like many reserves, driving over Cat Lake’s winter road requires passing over a lake with no bridge. When winter arrives and lake ice begins to form, crews repeatedly flood the lake to make the ice sturdy enough for heavy trucks. When the ice is ready, workers celebrate by spinning their grooming machines in circles on the frozen surface, a ritual called their “happy dance.”

To build the required snow bridges, crews use grooming machines to jam huge piles of snow into creeks. They let the snow settle for about 36 hours and then flood it to form icy crossings. The flowing water underneath naturally forms the ice into a culvert shape. “That’s why you need such a massive pile of snow to push out there, because all the water will take it away if there’s not enough,” Williams said.

A century ago, before planes and trucks became ubiquitous, remote reserves used tractor trains to pull supplies in sleds over the frozen landscape.

“It’s a big bulldozer that pulls trailers behind them, sometimes 10 of them, and that’s where all the fuel came from, the groceries. Because they didn’t have big planes at the time,” explained Chief Atlookan of Eabametoong.

“Back in the day, you didn’t worry about ice conditions — the ice was 40 inches thick.”

The remoteness of reserves is a direct outcome of the country’s colonial history. In 1867, the British Parliament claimed “Canada” as a colony by passing the British North America Act, which later became its constitution. It granted the federal government exclusive authority over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” and gave provinces authority over certain issues that affect First Nations, like mining.

Since European settlement, massive land grabs and the creation of reserves have left Indigenous peoples in “Canada” with only 0.2 percent of their original territories. Reserves were often deliberately sited in remote locations, away from critical waterways and productive farmland. There was never any intention of connecting reserves to cities; instead, they operated like jails, preventing people from moving off-reserve or seeking economic opportunities.

The federal government has a fiduciary responsibility to First Nations, as affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada. Similar to the “U.S.” government’s relationship with tribes, this means the government has a legal duty to act in the best interest of Indigenous people.

“Since the [court’s] decision, they’ve been looking for ways to offload their fiduciary obligations,” said Russ Diabo, a First Nations policy analyst and member of the Mohawk Nation at Kahnawake.

Although the federal government is obligated to provide the necessities of life on the reserve, like housing and water systems, federal funding formulas are unregulated and up to the government’s discretion, explained Shiri Pasternak, professor at Toronto Metropolitan University. As a result, there are huge discrepancies between what is needed and what is approved. “The underfunding of reserves amounts to systematic impoverishment,” she said.

This chronic underfunding means many First Nations experience crowded homes and broken-down water treatment plants. Although the federal government has committed to ensuring clean drinking water on reserves, more than 30 First Nations currently have long-term drinking water advisories. This includes Neskantaga in northern “Ontario,” which has been under a boil water advisory for three decades. Last year, in response to a lawsuit over “Canada’s” failure to provide clean drinking water to First Nations, the federal government argued it has no legal duty to ensure First Nations have clean water.

Despite the federal government’s history of abandoning its duties to First Nations, more communities are looking to Indigenous Services Canada, or ISC, for road funding. Of the 53 First Nations that depend on winter roads, 32 have asked ISC for funding to develop all-season roads.

Adapting to a warming climate

The sun’s pink light disappeared over the horizon and night fell over the frozen lake surrounding Wesley’s community. She sat in the driver’s seat of her 4×4 truck that was parked on the lake’s icy surface. She watched as workers, bundled up in coats, toques, and boots, drilled a hole in the ice and pumped murky lake water through a hose into a machine. The spout of the machine, pointed upward at a 40 degree angle, blasted a stream of snowflakes into the air.

A couple of years ago, Wesley asked her band council for a snowmaker.

“They thought I was crazy,” she said. “The chief finally told me, ‘Go ahead and buy a snowmaker.’”

Wesley has managed winter road construction for the past eight years. Her dad was the community’s economic development officer before her and was also responsible for the winter road. She grew up crawling around big machines; she would climb them and pretend the floor was lava.

When she took over her father’s job, men cast doubt on her ability to oversee winter road construction.

“She’s a girl, we don’t have to listen to her,” Wesley said, describing how they perceived her. “My dad told me, ‘You’re the boss. Tell them what to do.’” She said she proved herself, and now the workers respect her. They don’t ask questions, they do what she says.

The snowmaker is a short-term adaptation. Wesley said the community has asked the provincial and federal governments to support construction of its all-season road.

In an interview in March, ISC minister Patty Hajdu recognized the disappearing ice roads as an emergency.

“‘Emergency’ doesn’t even feel strong enough [to describe the situation],” she said. “It’s so urgent that we do more together to figure out what this next stage of living with climate change looks like for, in particular, remote communities.”

But Hajdu stopped short of committing funding for specific all-season roads. Instead, she said the cost will likely be shared but that the federal government was committed to funding all-season roads. “In theory, yes, but it isn’t as simple as a yes or no — it is project by project,” she said. “I can’t speak about specific amounts. I can’t speak about specific routes.”

She said the situation is more complex than it seems, and the province has complete control over which routes are prioritized and built.

ISC provided about CAD$260,000 for Cat Lake’s feasibility study to confirm potential routes for an all-season road. Hajdu said this is “an important step to the finalization of any infrastructure funding.”

Hajdu vowed not to tie all-season road funding to the acceptance of mining projects. “We should not be increasing funding for First Nations in any realm as a condition of approval for anything. That is very coercive and it’s very colonial,” she said.

“I wouldn’t believe it, because they use money as a way to coerce decisions. They may not directly openly tie it,” said Diabo, the policy analyst.

Last year, ISC allocated CAD$45 million for construction of a bridge and permanent road to Pikangikum First Nation, which has a winter road that crosses a lake. Although the government announcement did not mention mining, the road will also lead to a proposed lithium mine.

Each summer, more fires burn through northern forests, Diabo said.

“We’re in a time of emergency, and the issue of the disappearing winter roads is part of that.”

Under the dual pressures of climate emergencies and extractive industries, some communities will decide to go forward with mining to build all-season roads. “We’re seeing that already,” he added.

In October, Wesley visited the lake that First Mining wants to drain for its proposed Springpole project. The company’s open-pit mine is in the final stages of the permitting process, and the company expects to receive federal approval by the end of this year.

For Wesley, the area isn’t just beautiful, it’s a reminder of her connection as an Ojibway person to the water, trees, fish, and land. It’s a relationship she described by saying, “I belong to the land.”

“I was almost crying, because the land is forever going to be changed in that area,” she said. “We’re gonna have a hole in the ground that’s forever going to be there. I don’t know how not to be emotional about that. Those are my relatives.”

HILARY BEAUMONT

Hilary Beaumont is an investigative journalist covering the climate crisis and intersecting issues. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Al Jazeera, Rolling Stone, VICE News, The New Republic, and High Country News, among others.