“We Create Our Own Reality”: Empire and the illusion of International Law from Rafah to Caracas

Image Source: Department of State – Public Domain

The aide said that guys like me were “in what we call the reality-based community,” which he defined as people who “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality. That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will —we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

— A senior Bush administration aide to Ron Suskind, New York Times Magazine, 2004; often attributed to Karl Rove (who denies saying it). Suskind has never identified the source.

This boast has become the hallmark of U.S. imperialism, tracing a long lineage back to the Monroe Doctrine as an extension of the twisted notion of Manifest Destiny. This ideology, rooted in ethno-religious supremacy, claims that a particular people are divinely ordained to expand their territory and influence, much like Zionism and the greater Israel project, which asserts a chosen status based on religious belief. Such constructs have been used to justify movements of settler colonialism, founded on genocide and slavery, paving the way for U.S. global hegemony. This historical narrative extends through Vietnam, Korea, Panama, Desert Storm, Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, and currently, Gaza and Venezuela. Across both Democratic and Republican administrations, these actions embody American exceptionalism, arrogance, and unchecked imperial hubris.

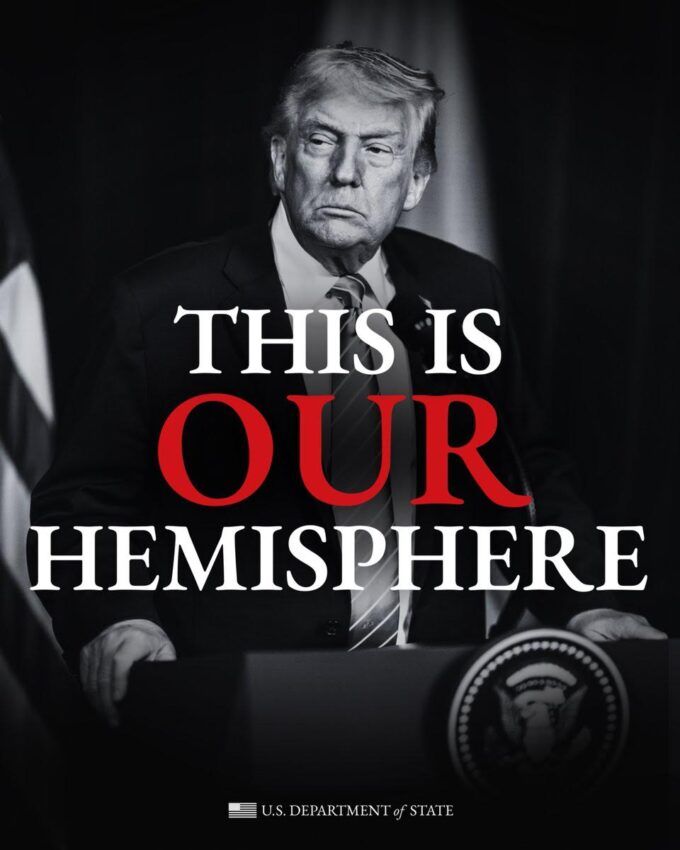

Say that law should bind the powerful and you are waved off as naïve — one of the “reality‑based.” From Belgrade to Baghdad, from Gaza to Caracas, Washington and its client states have treated the UN Charter and humanitarian law as props: invoked to punish enemies, waived to protect allies. The latest proof is the abduction of Venezuela’s elected president, Nicolás Maduro — seized in a U.S. operation under Donald Trump and flown to New York on laughable narcotrafficking charges — paired with open boasts about taking Venezuela’s oil. The facade of multilateralism has been stripped away; prerogative is now enforced by might.

This is not an anomaly. It is the arc of a decades‑long project: act first, justify later, dare the world to catch up.

A record written against the UN Charter

– Operation Desert Storm (1991, George H. W. Bush): UN‑backed expulsion devolved into the “Highway of Death” and a decade of catastrophic sanctions.

– Sanctions on Iraq (1991–2003, George H. W. Bush → Bill Clinton to Bush the second): Comprehensive sanctions devastated civilians; estimates counted hundreds of thousands of excess child deaths. In 1996, SecState Madeleine Albright said the price of half a million iraqi children was “worth it.”

– Yugoslavia/Kosovo (1999, Bill Clinton): NATO bombed without Security Council authorization, striking civilian infrastructure and gutting Article 2(4) which prohibits the threat or use of force any state’s territorial integrity of political independence.

– Iraq (2003, George W. Bush): Invaded on false WMD claims; the UK’s Chilcot Inquiry and U.S. Senate reviews documented manipulation; war crimes from Abu Ghraib to Fallujah.

– Afghanistan (2001–2021, George W. Bush → Barack Obama → Donald Trump → Joe Biden): From self‑defense to occupation, black sites, and globalized drone killings—including U.S. citizens; Biden’s botched Kabul strike (2021).

– Libya (2011, Barack Obama; SecState Hillary Clinton): UNSCR 1973 “protection” morphed into regime change, leaving a shattered state, a slave market in its wake, and a legal framework mocked by result.

– Syria (2014–, Barack Obama → Donald Trump → Trump 2024–): U.S. forces operate without Damascus’s consent or authorizing mandate; northeast oil effectively cordoned; the Caesar Act throttles recovery.

Earlier precedents and the Latin American playbook

– Korea (1950–1953, Truman → Eisenhower): Saturation bombing, massive civilian toll, armistice without peace.

– Vietnam/Indochina (1955–1975, Eisenhower → Kennedy → Johnson → Nixon → Ford): Escalation, carpet‑bombing, Agent Orange, Phoenix Program; the Pentagon Papers exposed official deceit.

– Guatemala (1954, Eisenhower): CIA‑backed coup against Árbenz over land reform; decades of terror followed.

– Cuba (1961–1962, Kennedy): Bay of Pigs and Operation Mongoose covert war.

– Dominican Republic (1965, Johnson): Invasion to crush reformist forces.

– Brazil (1964, Johnson): Backing for a military coup; later folded into Operation Condor.

– Chile (1970–1973, Nixon; Kissinger): Destabilization and the coup against Allende; Pinochet’s terror; declassified information shows US direct involvement.

– Operation Condor (mid‑1970s–1980s, Nixon → Ford → Carter → Reagan): Transnational assassination/torture network across South America with U.S. intelligence support or tolerance.

– Argentina “Dirty War” (1976–1983, Ford → Carter → Reagan): U.S. backing/tolerance amid disappearances.

– Nicaragua (1981–1990, Reagan → George H. W. Bush): Contra war; Iran‑Contra; the ICJ (Nicaragua v. U.S.) ruled against Washington—jurisdiction rejected.

– El Salvador (1979–1992, Carter → Reagan → Bush): Arming and financing amid massacres (El Mozote).

– Grenada (1983, Reagan): Invasion condemned by the UN General Assembly as illegal.

– Panama (1989, George H. W. Bush): Invasion with heavy civilian toll; UN condemnation.

– Haiti (1994, Clinton; 2004, George W. Bush): Interventions and political engineering; contested legality and outcomes.

– Colombia (late 1990s–, Clinton → George W. Bush → Obama): Plan Colombia militarization; displacement and abuses.

– Venezuela (2002, George W. Bush): U.S.‑blessed coup attempt; (2019–2021, Donald Trump): recognition and lawfare; (2020) Operation Gideon fiasco; (2026, Donald Trump): abduction of Maduro.

– School of the Americas (SOA/WHINSEC): Fort Benning program that trained numerous Latin American dictators later implicated in coups, torture, and massacres (Guatemala, El Salvador, Chile, Bolivia, Colombia).

Gaza: the reality that swallows any resemblance of a “rules based order” (Joe Biden and Donald Trump)

In January 2024 the International Court of Justice found South Africa’s genocide case against Israel plausible and ordered provisional measures. Under Joe Biden, Washington continuously armed Israel, wielded Security Council vetoes, and provided diplomatic cover. Under Donald Trump, that backing continues—vetoes, weapons, political impunity—repackaged through a farcical “peace plan” touting a “Gaza Riviera” and a “ceasefire” that is not: siege conditions persist, aid is throttled, and reconstruction is subordinated to occupation. Aid convoys are attacked; UN and NGO staff are killed; crossings are choked. As of January 1, 2026, Israeli authorities have banned 37 aid groups from Gaza; Doctors Without Borders — Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) — reports teams blocked and attacked; an Israeli official smeared MSF as “Terrorists Without Borders.” When law threatens an ally, it is reinterpreted until it disappears.

Empire in the Americas, redux

The Monroe Doctrine never died; it rebrands as “leadership.” When elections comply, sovereignty is sacred. When they don’t: sanctions, coups, covert ops, indictments — and now kidnapping dressed as jurisdiction. Trump’s updated playbook — earning the moniker the “Donroe Doctrine”— runs from abducting Maduro to threats against Colombia and even the fanciful bid to “get” Greenland. The message to the hemisphere is blunt: it’s ours.

Venezuela has endured the full spectrum. UN‑condemned sanctions crushed public health; PDVSA (the state-owned oil and natural gas company of Venezuela) was choked; CITGO carved up. In 2020, Trump posted a $15 million bounty on Maduro with sweeping DOJ indictments, Biden raised the bounty to $25 million. Operation Gideon attempted a comic‑opera amphibious incursion. Diplomat Alex Saab was seized and extradited. Now, with Maduro in a US jail — and Trump musing about taking a “huge amount” of Venezuelan oil — Washington asserts empire’s prerogative: abduct a foreign head of state and try him under domestic law. No Security Council referral. No consent. No neutral venue. Normalize this, and head‑of‑state immunity collapses.

Follow the resources

Read the map: Orinoco heavy crude, Arco Minero gold and critical minerals, offshore gas; Iraqi hydrocarbons; Syria’s northeast oil; eastern Mediterranean Palestinian gas, Greenland’s minerals. Policy follows pipelines, ports, and mining pits. When officials call the hemisphere “ours,” they’re staking claims.

The domestic mirror: law as theater, impunity as practice

The imperial actions abroad reverberate at home. The Patriot Act normalized mass surveillance; Edward Snowden’s disclosures exposed the data dragnets and FISA rubber stamps. “Terror Tuesday” normalized kill lists under Obama, expanded under Trump and are preserved in core agencies of the security surveillance aparatus. Extra judicial killings of US citizens became accepted practice. Guantánamo endures; ICE runs a carceral archipelago and sends storm troopers onto the streets of US cities, now gunning down and killing upstanding US citizens being dubbed as dometic terrorists at the whim of a lunatic administration. The forms are legal; the substance is gangster style/war lord rule with impunity.

Israel’s place in a system of genocidal impunity

For decades Israel has defied Security Council resolutions on settlements and annexation; blockaded and bombed Gaza; criminalized humanitarian work; and now faces a plausible ICJ genocide finding. Time after time, Israel and the United States stand nearly alone against global consensus: U.S. vetoes of Gaza ceasefire resolutions; lopsided UNGA votes for humanitarian access; rejection and intimidation of the ICC under the Rome Statute; efforts to sideline duties under the Genocide Convention. Washington sanctioned ICC officials under Trump, expelled and sanctioned UN special Raporteur Francesca Albanese, refuses Rome Statute membership, and insists the court lacks jurisdiction over allies. Israel signed but never ratified the Statute and rejects ICC jurisdiction in Palestine, even as Palestians accepted it. The result is genocidal impunity for clients of empire and the practical impotence of “international law” against U.S./Israeli power.

Europe’s vassal states and the war economy

Across Western Europe and the UK, governments tow Washington’s line while public sentiment increasingly rejects it. From London to Paris and Berlin to Rome, streets fill with Palestine solidarity and now solidarity for Venezuela and againts US imperialism; unions and students resist a permanent war economy. Elites still farcically sermonize about “rules” as wages stagnate and inflation — especially energy — erodes living standards. The social contract is traded for defense contracts; dissent is policed while profiteers prosper.

Reality, manufactured

International law has only ever existed in theory; empire decides practice. The Suskind quote reads like an operating manual: manufacture “reality” with devastating sanctions, rigged indictments, drone warfare, military intervention and false narratives; dare the world to catch up. When courts and rapporteurs do, move the goalposts. Hypocrisy is a weapon —exhausting the masses, fogging the record, buying time.

A weary public — and the Nobel as cover

In the United States, people are weary of endless wars, surveillance creep, ICE, and the rising cost of living — and opposed, on basic moral grounds, to complicity in genocide. The Nobel Peace Prize often functions as elite cover: Kissinger’s award sat atop bombing maps; Obama received it before becoming the drone bomber in chief, the brand now routinely lauds neoliberal respectability. This year Julian Assange filed legal action in Sweden to block payment of the Peace Prize cash award to Venesuela’s María Corina Machado — underscoring how “peace” laureates and money are folded into regime‑change politics.

What is to be done

Name the hierarchy — friends above law, foes beneath it — and lift civilian‑crushing sanctions. Enforce ICJ orders and the Genocide Convention with real costs, including arms embargoes and sanctions where there is a plausible risk of genocide. Defend the right to dissent at home and recentre political economy. Above all, build an international movement from below that puts people and the planet before profit and war‑making. Its beginnings are visible in the global struggle for Palestinian liberation, which must remain central as the definitive fight against the legacy of genocide and settler colonialism, and be linked to all peoples’ movements for self‑determination and liberation against every form of imperial aggression—from Venezuela to the Congo to Yemen and Sudan and even to Ukraine. Through strikes, boycotts, divestment, sanctuary, debt relief, demilitarization, public goods, and a just energy transition, make solidarity a practical force.

The reality‑based community was never naive. It insists that facts and law should bind the powerful. The alternative is rule by spectacle and force — kidnappings as court process, famine as “counterterrorism,” war as policy. Empire has cast itself as history’s actor. The task is to refuse the role of spectator, to make international law more than just a prop and freedom and justice more than empty slogans.

Selected sources:

– Ron Suskind, “Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush,” New York Times Magazine, Oct. 17, 2004.

– The Guardian, “Nicolás Maduro appears in New York court on US narcotrafficking charges,” Jan. 5, 2026.

– ICJ, South Africa v. Israel, Provisional Measures (2024–2025).

– BBC, “Israel bans dozens of aid groups from operating in Gaza,” Jan. 1, 2026.

– NPR, “Israel steps up campaign against aid NGOs in Gaza,” Dec. 30, 2025.

– Arab News, Jan. 1, 2026.

– Pentagon Papers (Vietnam); National Security Archive (Guatemala 1954; Chile 1973; Condor; Iran‑Contra); Church Committee reports.

– ICJ, Nicaragua v. United States (1986).

– Human Rights Watch/Amnesty on Panama 1989, El Salvador, Argentina, Condor.

– SOA Watch; WHINSEC/DoD documents on School of the Americas.

– The Iraq Inquiry (Chilcot Report, 2016); U.S. SSCI on Iraq WMD.

– Bureau of Investigative Journalism (drones); ACLU/Just Security (targeted killing).

– UN reporting on UNSCR 1973 (Libya); Amnesty/HRW post‑intervention.

– International Crisis Group/Just Security (Syria, Caesar Act).

– Rome Statute (1998); EO 13928 (2020) on ICC; ICC situation files (Palestine/Afghanistan); Genocide Convention analyses.

– UN SR Alena Douhan on Venezuela sanctions; CEPR sanctions‑mortality analysis; filings on CITGO; reporting on Operation Gideon and Alex Saab.

Michael Leonardi lives in Italy and can be reached at michaeleleonardi@gmail.com

Democracy Challenged: Who Governs Gaza? Who Runs Venezuela? “Who Does New York Belong To?”

Photograph Source: NYC Mayor’s Office – CC BY 3.0

2025 was an annus horribilis for democracy. Within the United States, Donald Trump, his administration, Congress, complicit state legislatures, and the Supreme Court systematically attacked civil liberties and weakened core democratic institutions. Internationally, there were at least two examples of undemocratic impositions. U.N. Security Council (SC) Resolution 2803 created a so-called “Board of Peace,” chaired by Donald Trump, and a temporary International Stabilization Force to govern Gaza without the consent of the those who live there. Recently, Trump announced that Marco Rubio, Pete Hegseth and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff would “run” Venezuela, an extraordinary assertion of external control over another state’s political future.

Did 2026 start better?

Yes. Zohran Mamdani’s taking office as Mayor of New York City offers several reasons for democratic optimism. As the first-ever mayor to be sworn in on a Quran, the 34 year-old surprise winner has shown a progressive, democratic sensitivity and agenda that offers promises for New York City and beyond. Mamdani’s election could signal a revival of true democratic politics in the United States, and an eventual model for democratic governance elsewhere.

At his January 1 inauguration, Mamdani gave a moving presentation of new possibilities for democracy after being sworn in as mayor by Bernie Sanders and following an opening speech by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“I stand alongside countless more New Yorkers watching from cramped kitchens in Flushing and barbershops in East New York, from cellphones propped against the dashboards of parked taxi cabs at LaGuardia, from hospitals in Mott Haven and libraries in El Barrio that have too long known only neglect. I stand alongside construction workers in steel-toed boots and halal cart vendors whose knees ache from working all day.”

The new mayor asked, “Who does New York belong to?”

“For much of our history, the response from City Hall has been simple: It belongs only to the wealthy and well-connected,” he answered.

He then offered a very different answer about whom New York could belong to: “New York could belong to more than just a privileged few. It could belong to those who operate our subways and rake our parks, those who feed us biryani and beef patties, picanha and pastrami on rye. And they knew that this belief could be made true if only government dared to work hardest for those who work hardest.”

“[I]f only government dared to work hardest for those who work hardest,” Mamdani declared at the very moment of Trump’s new Gilded Age where the richest 1 percent of Americans own roughly 30% of national wealth and the top 10% control nearly two-thirds. The chief executive of JP Morgan Chase made $770 million in 2025. A recent economic study shows that in recent decades the Supreme Court has favored the rich.

Mamdani’s inaugural speech presented what many consider a radical position. President Trump has derided Mamdani as a “communist fanatic.” Yet when Trump met Mamdani in the Oval Office in November, the New York Times reported that “they were just two iconoclastic New Yorkers who were all smiles.” “The better he does, the happier I am,” Trump said. “Because he has a chance to really do something great for New York,” the president added. “It was a great meeting.”

There is no question that Mamdani will face staunch opposition as mayor. Several very wealthy individuals have threatened to leave New York if he raises city income tax on million-dollar earners or increases corporate taxes. John Catsimatidis, the billionaire owner of the grocery chain Gristedes, told the Free Press in June he may “consider closing our supermarkets and selling the business” in the event of a Mamdani victory.

There were also obvious religious criticisms of the city’s first Muslim mayor. “On his very first day as @NYCMayor, Mamdani shows his true face: He scraps the IHRA definition of antisemitism and lifts restrictions on boycotting Israel. This isn’t leadership. It’s antisemitic gasoline on an open fire,” the Israel Foreign Ministry wrote in a post on the social platform X.

But the essential criticisms of Mamdani lie in the class position he has taken. Bill Reilly claimed in The Wrap that “He’s a communist…Seizing the means of production.” Republican Rep. Nicole Malliotakis argued in The Times of India, that his ideas were “straight out of Karl Marx’s Communist playbook,” and Bishop Robert Barron, writing in the New York Post, cited Mamdani’s embrace of “the warmth of collectivism,” that collectivism has historically led to oppression.

Is Mamdani merely a New York phenomenon? Will his victory and positions have influence outside the five boroughs? He seems not afraid to stand up for his beliefs beyond New York-specific issues. He challenged President Trump after the Venezuela strikes and kidnapping of Maduro. “I called the president and spoke with him directly to register my opposition to this act,” he said. The New York Times reported on the call in which Mamdani recounted that “he told Mr. Trump that he was ‘opposed to a pursuit of regime change, to the violation of federal and international law.’”

It is uncertain that Mamdani will succeed in implementing some of his ambitious policy proposals, such as free childcare, free bus service, and a rent freeze for those living in rent-stabilized apartments. Nevertheless, he declared, “Beginning today, we will govern expansively and audaciously. We may not always succeed. But never we will be accused of lacking the courage to try.”

The essence of Mamdani’s “courage to try” is his commitment to re-establish democracy in New York City. His inaugural speech was a clarion call for the city to belong to all New Yorkers, regardless of wealth, class, or religion. Internationally, based on his call to the White House, the same principles apply; respecting international law as a just system should give equal rights to all peoples and states – the Preamble of the United Nations Charter does begin with “We the Peoples.”

Amid the undemocratic Trump 2.0, U.N. Security Council Resolution 2803 and the arrogant gunboat diplomacy of the so-called “Donroe Doctrine,” there is a potential shining light coming from New York City, at least based on Mamdani’s inaugural speech. Given the current gloomy global situation, a little light is more than welcome as we begin the new year, still hoping, like Abraham Lincoln, that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”