UPDATED

Last Saturday (January 3th), a massive US military attack, concentrating the largest naval aggressor force ever assembled in the Americas in the Caribbean, kidnapped Nicolas Maduro and decapitated the country’s government. Since then, Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio have multiplied threats. They spoke of a “second attack.” They boasted that “any member of the government or armed forces” could suffer the same fate as Maduro. They added that Delcy Rodriguez, the acting vice president, could face “something worse .” In the most recent outburst, Trump himself “assured” in a social media post on January 6th that Washington would demand 30 to 50 million barrels of oil from Caracas (two months of production), the revenue from which he would personally manage…

On the same day this latest intimidation was uttered, Delcy Rodriguez made her first appearance on the streets of Caracas as acting president. She chose a symbolic location as the setting : the José Félix Ribas Socialist Commune, part of the Chavista project (only recently resumed by Maduro) to create institutions of power and popular economic initiative . She was categorical: “here the people govern, here there is constitutional power.” She denounced Trump’s action as “unilateral armed aggression.” She demanded that “the harassment of Venezuela and the aggression against the people of Bolívar cease,” and that the president be released.

The dice are still rolling, in Venezuela and throughout Latin America. The swift military action of the United States and Trump’s pronouncements since then mark a turning point in relations between Washington and the region. International law has been violated in multiple ways, and in an undisguised manner. The White House announces the return of the Monroe Doctrine and the Big Stick strategy, now in a worsened version (the “Donroe Doctrine” ). But a deeper examination of the facts, which will follow, reveals that its power has limits.

They appear in Trump’s own decisions. Despite the immense military power he possesses, and his effort to concentrate it in the Americas (the “western hemisphere” of the Monroe Doctrine), the president cannot launch a large-scale invasion, as his recent predecessors did in Iraq and Afghanistan. As a result, he also hesitated to take the step that would seem natural after the success of the attack: to go further and attempt regime change.

The contradiction between Trump’s plans and his actual powers opens a breach, and the main objective of this text is to explore it. Latin America, and Brazil in particular, can no longer maintain the same relations with the United States as before – but governments and public opinion are slow to realize this.

This is not about issuing protest statements (those that Brazil has sponsored or signed so far are reasonable). The Donroe Doctrine, the pioneering attack on Venezuela, and Trump’s subsequent threats to other countries in the region constitute, together, a permanent declaration of war. In this sense, the empire is naked – for it has stripped itself of the trappings that associated it, in the past, with “democracy,” “freedom,” or the “rule of law . “

But potentially aggressive powers take advantage of two kinds of vulnerabilities. The first, fundamental one, is the prolonged absence of national projects. A primary focus of neoliberalism, most Latin American countries remain subservient – even now, when this ideology is in tatters – to the belief in “market solutions.” Brazil is part of this group.

The second weakness is more specific, yet more urgent. For this very reason, it suggests a starting point for action. The gaps in the White House’s power are especially serious in three dimensions: a) information technologies, networked communication platforms, and artificial intelligence, where American big tech companies , associated with the far right, exert complete dominance; b) the Armed Forces, whose weaponry, communication, and logistics are subordinated to the United States; c) diplomacy, which remains incapable of seeing – much less exploiting – the new possibilities opened up by the decline of the Eurocentric order. It remains particularly blind, as will be seen, to the multiple overtures launched by China.

Certain risks are also opportunities. For three decades, the Brazilian left has been undergoing a process of institutionalization that has distanced it from thinking about – and projecting to the population – a historical horizon. Now there is a strident warning sign. Will it help awaken it from its lethargy?

I.

The assault

Don’t go hunting for traitors. A brutal imbalance of forces made the kidnapping possible.

Just a few hours separate the two surprising events – one dependent on the other. Around two in the morning on Saturday (January 3rd), after months of preparations, the weight of the most powerful military forces on the planet fell like a lightning bolt on Caracas. Operation Absolute Resolve was beginning , which would unfold in just over two hours. The pilots of 150 aircraft, stationed at air bases and on warships deployed to the Caribbean, finally received the order to begin the mission that had been exhaustively rehearsed for months.

In a few minutes, four strategic targets for the defense of Venezuela were destroyed – bringing the country to its knees, as reported by Carla Ferreira : Fort Tiuna , the country’s main military installation, headquarters The Ministry of Defense and the Strategic Command of the Armed Forces were destroyed; the La Carlota Air Base , the logistical hub for the protection of the capital; the General Command of the Bolivarian Militia, the brains behind the armed civilian resistance forces, located very close to the Miraflores Presidential Palace; and the Port of La Guaira , which supplies the capital with medical supplies, consumer goods, and manufactured goods. The anti-aircraft batteries that were supposed to protect Caracas were also destroyed.

As the planes moved, among them powerful F-18s, F-22s, and F-35s – opened a lethal corridor . An electronic attack, produced by specialized Boeing Growlers , put Venezuela in a “cyber blackout,” and increased its defenses by blocking interception possibilities. Through this large opening , flying at very low altitudes and invisible to radar, Chinook helicopters penetrated . Inside were hundreds of soldiers from the elite Delta Force. They had been briefed – by CIA agents, spy drones, and possibly informants within the Venezuelan security apparatus – on the precise location (Fort Tiuna) where Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were that night. They knew its interior in detail, having simulated the operation in scenarios that reproduced it, on a 1:1 scale, at the Joint Special Operations Command in the US state of Kentucky.

The final phase lasted just over half an hour. Maduro and Cilia were kidnapped, handcuffed, and taken to the small aircraft carrier USS Iwo Jima, from where they departed for the Guantanamo naval base and from there, by helicopter, to New York. About eighty members of Maduro’s security detail – including 32 Cubans – were murdered by the invaders. No American soldiers died, says the Pentagon . The US war budget , which will exceed $1 trillion in 2026, is the largest in the world, and greater than the combined budgets of the next ten countries. It is equivalent to the GDP of Colombia or Belgium. From a military point of view, the operation was a success.

II.

The nervous mouth:

All of Latin America is now under threat, Trump announces.

The paths of politics are more tortuous and complex. It was around 1:30 PM on that same Saturday (January 3rd) when Donald Trump spoke to the press for the first time, at his mansion in Florida, about Maduro’s kidnapping . How to defend the invasion and bombing of a sovereign country – which has never attacked or threatened the US – and the kidnapping of its head of state? Beyond the inherent difficulty of the problem, there were aggravating factors. The hypothesis that Venezuela supplies cocaine to the US is implausible , according to the US intelligence agencies themselves. The US has never filed any complaint about this with the UN Security Council or the International Court of Justice. And, for geopolitical and partisan reasons, Trump himself has just released international drug trafficker Juan Orlando Hernández, former president of Honduras, from prison; he was sentenced to 45 years in a New York court after extradition and due legal process.

Trump’s response will continue to shape international relations long afterward.

That the spectacular action of Delta Force in Caracas has been lost in the dust of time. On January 3rd and 4th, in successive statements by its leaders, the United States announced that it would attempt to impose, throughout the Americas, an aggravated version of the Monroe Doctrine (of 1823) and the Big Stick Ideology ( of 1904). The threat was explicit, in theory, in the new National Security Strategy made public by the White House in December 2025. But the extent of Washington’s covetousness for Latin American riches and the intention to usurp the sovereignty of the continent’s states would be brutally exposed later.

The intimidating outburst first emanated from Trump’s own throat. “The United States’ domination of the Americas will never be questioned again. [That] will not happen,” the president told reporters. Maduro’s kidnapping was, predictably, linked to his alleged involvement in cocaine production. But it soon became clear that this was merely a pretext, because the president went on to describe the fate he intends to give… to Venezuelan oil. “We will manage it professionally, we have the largest oil companies on the planet. We will invest billions and billions of dollars.” To ensure this control, under the new strategy, Trump said he did not rule out the possibility of a military invasion (boots on the ground ) [although he is very afraid to trigger it, as will be seen].

It would soon become clear that the White House’s target encompasses much more than Venezuela. On Sunday morning (January 4th), speaking to Fox News , Trump extended the threat to Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum. Asked if the attack on Caracas suggested anything to Claudia, he promptly replied: “She’s not governing her country – it’s the cartels (…) Something needs to be done.” On the same day, in an interview with The Atlantic magazine , the vociferations turned against Greenland: “We need it, for our defense.” And later, aboard the presidential plane, his nervous mouth sought out Gustavo Petro, the president of Colombia: The country “is also very sick, governed by a sick man, who likes to produce cocaine and sell it to the United States — and he won’t continue doing that for much longer”…

III. A remote-controlled government?

Trump and Rubio want to control Venezuela from a distance.

In Trump’s regression to the Monroe Doctrine and the Big Stick ideology, there is a striking and paradoxical innovation. It is exposed in the attack on Venezuela. At least for the moment, the United States is not seeking regime change , which it has pursued throughout the world for decades, under both Republican and Democratic governments. They demand a total reorientation of policy . Maduro was kidnapped, but not killed (unlike Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi). Furthermore – and much more importantly – Trump and his advisors have said they are offering both Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez and members of the country’s state and military apparatus a consolation prize. They can remain in their posts and enjoy their respective comforts, provided that… they obey their new masters. In this attempt at an arrangement, bizarre and extremely uncertain, lies one of the keys to understanding what is happening now in both Caracas and Washington.

The experiment began to be rehearsed in Saturday’s interview in Palm Beach. An imperial Trump expressed the White House’s intention to “run the country . ” But, to the astonishment and disappointment of many, he dismissed the possibility of installing opposition figure Maria Corina Machado in power. Identified with the international far-right, she possesses some political capital and had recently attempted to court American corporations with the promise of “massive privatization” of Venezuelan oil, gold, and infrastructure. In her own words, “a $1.9 trillion opportunity”…

Trump preferred to back Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodriguez, who, according to him, will govern under very special conditions. “Marco [Rubio, Secretary of State] is working on this directly and just spoke with her. Essentially, she is willing to do what I deem necessary to make Venezuela great again”… However, he threatened: “We are ready to launch a second, much larger attack if necessary.” He went further: “All political and military figures in Venezuela should understand that what happened to Maduro could happen to them as well . ” And he made it clear that the situation will persist until the US can “organize a safe transition.”

A few hours later, speaking on state television, Delcy suggested a different course of action. She called Washington’s intervention “barbaric,” reaffirmed that Maduro is “the only president of the country,” denounced his “kidnapping” (using the precise term), and called for his release. That was enough for Trump and his advisors to return to the attack. On Sunday morning, Secretary Marco Rubio announced in an interview that the US will continue blocking Venezuelan oil exports until the state-owned company that exploits most of the oil fields (PDVSA) opens itself to foreign investment – especially American investment. “[The blockade] will remain until we see changes, not only to favor the national interest of the US, which is the number one objective, but also to promote a better future for the people.”

Hours later, the president himself returned to the topic in another contact with journalists . Asked about oil, he promptly replied: “We need full access. To oil and other things in the country.” And regarding who wields power in Caracas, he assured: “We are dealing with whoever took office. Don’t ask me who is in charge , because I will answer, and that could be very controversial.” The reporter insisted: “What does that mean?” “It means we are in charge,” Trump replied.

Repeated threats made too often may reveal doubt about one’s ability to carry them out.

IV.

The limits

Contrary to what he tries to make people believe, the emperor cannot do everything.

Invading a sovereign country, kidnapping its president, and withdrawing. Renouncing “regime change.” Getting rid of an ally like Maria Corina Machado. Believing in controlling a government through coercion. What led Trump to follow, in the operation against Venezuela, a pattern so different from those normally employed in interventions carried out by the United States? The facts are recent and are developing. More time will be needed for definitive answers. However, based on an examination of objective events and trends, it is possible to formulate good hypotheses.

The first relates to one aspect of the decline of American power: the breakdown of the social consensus necessary for wars. Trump captured this sentiment. One of the key points of his speeches in the race for the White House was the denunciation of interventions abroad. In condemning them, he pointed to them as a product of the establishment’s actions. He insisted on the cost they imposed on Americans, how much they benefited the military-industrial complex, and how they diverted resources that, according to him, could have “made America great again” (MAGA). The narrative became hegemonic. In December 2025, according to polls cited by The Conversation website , 63% of American voters rejected military action against Venezuela.

This is probably the main reason for discarding Maria Corina. Putting her in power would mean a huge provocation for the supporters of Chavismo. The country would plunge into instability – the worst possible scenario for the enormous investments needed in the oil industry and its vulnerable facilities. Having installed her in the Miraflores Palace, the US would need to defend her. Trump would clash both with a large majority of the electorate and with his own discourse.

The second hypothesis relates to Trump’s particular choices in trying to counter the decline. He refuses to resort to the international institutions built after World War II to sustain American hegemony. He calls them “globalist.” In bilateral relations with other countries, he maximizes the economic and military power of the US to extract concessions. (It is worth recalling his significant victories in trade agreements with the European Union and Japan after imposing the “tariff hike”). He seeks to add to this power his personal brutality: supremacist impulses, constant harassment, insults, and the habitual use of lies and falsification. He is obsessed with restoring the power of American corporations. Aren’t these precisely the central elements of his aggression against Venezuela and his attempt to remotely control its rulers?

* * *

Will this recipe be effective in Venezuela? It is, evidently, too early to know. The US show of force was impressive and devastating. The kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro leaves Chavismo deprived of its main popular leader and the point of unity among all its factions. The notorious bureaucratization of some of its members holding positions in the State tends to make Trump’s abject proposal tempting. The pressure will be amplified by the blockade of Venezuelan oil shipments , which the US has not relaxed and which deprives the country of its main source of foreign exchange.

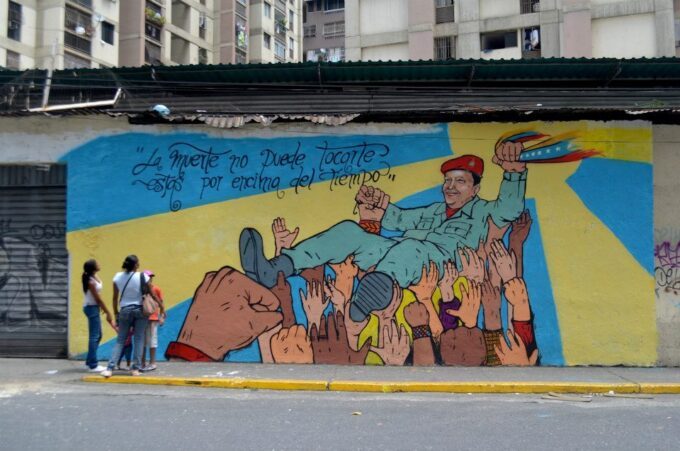

But there is another side to Chavismo. The one that was forged in the commander’s historical battles. The one that was inspired by the anti-imperialist project and the broad redistribution of oil wealth. The one that participated in processes such as the 1999 Popular Constituent Assembly and the multiple attempts to invent a popular democracy capable of overcoming the limits of liberal institutions. The one that was enthusiastic about Maduro’s efforts to revive the “popular communes” after the debacle in the 2024 presidential elections. Unlike what happened in the military dictatorships sponsored by Washington during the Cold War, this tradition is not being destroyed – and it is unlikely to be while Delcy Rodriguez remains at the head of the government. Trump’s project, as we have seen, is different.

What will happen when the two sides of this coin – the attempt to force Chavismo to act against what constituted it; and the continued power of a movement whose rebellious origins have not been lost – become incompatible? Trump’s intervention has once again placed Venezuela at the center of the global geopolitical stage. Everything that happens there will have repercussions. Will Trump order Delcy Rodriguez to execute his plan? Will she acquiesce? If she does, will there be a revolt? What will happen then?

The enormous shock caused by the swift action of the US on Saturday may have led some to believe that a chapter in Latin American history was closing. In Venezuela, on the contrary, a new page in the struggle for the country’s future – extremely difficult and arduous, but not lost – may be opening.

But what about Latin America as a whole, and Brazil in particular?

V.

The opportunity

: Faced with the Donroe Doctrine, Latin America and Brazil either bow down or reinvent themselves.

In May 2025, an extensive article in the digital magazine Defesanet revealed that members of the Trump administration coveted the infrastructure of Fernando de Noronha and the Natal-RN Air Force Base. The White House’s new National Security Strategy was being drafted. The publication found that diplomats from Trump’s inner circle had raised the issue in contacts with Brazilian politicians and military personnel. They intended to install surveillance and power projection structures (equipment and airports) over the South Atlantic in both locations, which would naturally require the creation of operational enclaves, shielded from Brazilian authorities. They brandished, as an argument, a bizarre “functional right of strategic reuse”—the same one the White House has used to try to regain control of the Panama Canal. Defesanet itself considered: “the name for this is colony”…

The episode reveals, almost in the form of a caricature, a new reality. Faced with the Donroe Doctrine, and what it has already produced in Venezuela, the governments and societies of Latin America have two alternatives. If they bow down or remain silent, they will deepen the lethargy and the feeling of impotence that has spread throughout the region for three decades, since the neoliberal project became hegemonic. The structural impasses – inequality, productive regression, technological backwardness, devastation of nature, institutions alienated from real life, and so many others – will remain unaddressed. The countries will be vassals of a declining power, condemned to the miseries of late capitalism and to a peripheral condition.

But Trump’s intimidation tactics and his desire to tighten the noose on colonization may, paradoxically, sound the wake-up call. In this scenario, the awareness that there is a risk of deeper subjugation leads to the identification of vulnerabilities. And the effort to remedy them triggers a national mobilization capable of reviving ideas that are currently dormant: such as national project , reconstruction , and political horizon .

In this movement, three objectives can be strategic: a) Digital Sovereignty; b) revision of the National Defense Policy; and c) foreign policy focused on building a post-Eurocentric order and partnerships with the Global South. These are challenging. They will require persistent and prolonged construction. However, they are clear, capable of mobilizing and generating positive secondary effects.

The fight for Digital Sovereignty is, of the three, the most crucial, urgent, and complex. But perhaps it is the one that can most unleash political and economic energies currently contained. The current scenario is contradictory. In some aspects, the dependence on the US is dramatic: Brazil finds itself surrendered to its big tech companies. A study conducted in 2025 by researchers Sérgio Amadeu and Jeff Xiong demonstrated that the country hosts almost all of the strategic data it generates on servers belonging to American corporations. This includes data from Brazilian universities, research and technology centers, the SUS (Unified Health System), IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), the Federal Revenue Service, and the superior courts (including the STF and TSE), for example.

The development of basic software is in the same subservient position – to the point, for example, that “ Google and Microsoft host the emails and data repositories (drive) of 154 Brazilian public universities.” Also foreign are the platforms used almost universally in the country for internet research (Google), personal communication via messaging (Whatsapp-Meta), social networks (Facebook and Instagram-Meta or TikTok-Bytedance), or for personal transportation, delivery, accommodation, one-off service contracts, and many others. All of them capture, process, distribute through algorithms, and monetize and commercialize both communication consciously generated by the population (a text or video post on a social network, for example) and data generated involuntarily (such as any form filled out online). Algorithmic programming, now reinforced by artificial intelligence, has enormous power to influence behavior – including electoral behavior. And the alignment of big tech companies with far-right policies has become blatant since Trump’s inauguration.

Conversely, the country has two enormous strengths in the same field: a large contingent of highly trained programmers and developers (who today, due to a lack of alternatives, work mainly for big tech companies ) and informed, creative social movements capable of formulating policy for the area. If the fight for digital sovereignty becomes a state priority, overcoming vulnerability could advance consistently and relatively quickly.

In 2025, hacktivist Uirá Porã outlined, in an interview with Outras Palavras , a possible roadmap: 1. Build, starting from universities, a Brazilian network of public data centers ; 2. Recover the two state-owned companies in the sector (Dataprev and Serpro), currently entangled in subservient partnerships with US big tech companies ; 3. Articulate, within these companies and regionally linked to university data centers , teams of developers willing to produce applications for municipalities, other public entities, companies, and civil society. In this design, Digital Sovereignty ceases to be merely a strategic objective of the State and begins to unfold into services to society, stimulating the mass training of qualified professionals and a space for the development of awareness and social reinvention.

* * *

A revision of the National Defense Policy is necessary to confront an even more glaring weakness. The very orientation of some of the Navy’s frigates in the oceans now depends… on Elon Musk’s Stalink. But not only that. Historian Manuel Domingos, who studies the Brazilian Armed Forces in depth, recalls in a recent text that the Brazilian Armed Forces have lived, since the time of Baron Rio Branco, with the fetish of dependence on technology purchased from Western powers. Defense is not understood as an organic action of Brazilian society – which could lead to autonomous technological development. Packages are acquired – the Swedish Gripen fighters or French submarines, for example – that subject the country to multiple dependencies.

In June 2024, for example, the US Department of Justice requested that Saab, the manufacturer of the Gripen fighter jets sold to Brazil, provide “clarifications” about the operation. The magazine Sociedade Militar warned at the time: “The move raises suspicions about possible interference aimed, in fact, at keeping Brazil in a state of dependence on the US (…) The Gripen, despite being a modern fighter jet, depends on a chain of international suppliers: the engine is American, the ejection system is British, and several other components come from different parts of the world. This means that if at any point the US or the UK decide to put the brakes on, for political or commercial reasons, these fighter jets would be grounded. And it’s not just theory – history has already shown this in several episodes…”

Freeing the country from such dependence, to prevent the Armed Forces’ own equipment from being at risk of being blocked, may be an understandable and politicized project. But, as in the case of Digital Sovereignty, it goes beyond the interests of the State. Manuel Domingos argues in his text that the National Defense Policy, published in May 2024, “turned to dust in the early hours of last Saturday,” when the US demonstrated what it is willing to do. But he recalls that a review could, in addition to technological autonomy, bring into debate other points equally important for a national project. Among them, guiding the Armed Forces towards their role of defending the territory (challenging the tendencies to turn them against “internal enemies”) and also considering, in the military field, a policy of integration of South America – including to have more strength against real threats…

The Trump threat, as we can see, may lead Brazil to reflect on itself. But in a time of global challenges – such as growing inequalities, the risks of environmental collapse, and the constant threats of war – isn’t it also necessary to rethink geopolitical alliances?

VI. Alliances

To confront the US, Latin America needs allies. China is stepping forward.

A third weakness becomes apparent when analyzing the conditions for Latin America and Brazil to confront the new threatening attitude of the US. Especially during Lula’s third term, foreign policy became timid, conventional, and incapable of envisioning partnerships and collaborations outside the Eurocentric order.

Gone are the days of Foreign Minister Celso Amorim and his bold and surprising initiatives – his central role in the creation of BRICS, the organization of a summit between South America and Arab countries (which startled Washington), or the attempt (with Turkey) to broker a peace agreement between the United States and Iran (sabotaged by Hillary Clinton). Under Mauro Vieira, what prevails in Itamaraty is what economist Paulo Nogueira Batista Jr. , with biting irony, called the “permanent visa group in the US.” These are the diplomats who fear (even since the Trump administration) any gesture that might upset the US – especially strategic rapprochements with BRICS and China.

Although the Chinese have long been Brazil’s main trading partners, the country has established a relationship with them that reproduces its colonial past and its productive regression. It exports primary products – especially soybeans and iron ore. It imports technological goods and services. Two proposals from Beijing, launched in recent months – the Global Governance Initiative , from September 2025, and the Policy Document for Latin America , from December – suggest that the bilateral agenda could be very different.

The first proposal outlines five seemingly generic propositions that directly clash with Trump’s “imperial right to intervention.” Three stand out: a) “egalitarian sovereignty” (“all countries, regardless of size, strength, or wealth, will have their sovereignty and dignity respected, their internal affairs free from external interference, and the right to independently choose their social system and level of development”), b) respect for international law and UN bodies; c) a “people-centered approach” (“the well-being of populations is the ultimate purpose of global governance”). The second, longer and more detailed proposal formulates specific collaboration proposals, encompassing, among others, areas and themes relevant to Brazil: (re)industrialization, nature preservation, clean energy, science and technology (including the internet and AI), military exchange, and others.

Neither document received significant attention in the Brazilian mainstream media. Both deserve careful examination. It’s not about proposing an “alignment with China,” as those opposed to the partnership sometimes pejoratively proclaim. Rather, it’s about recognizing that while Washington clearly announces an imperialist and aggressive stance, there is a gesture of a different nature. This gesture comes from a country in the Global South that suffered a “century of humiliation” at the hands of Eurocentric powers – but recovered through a popular revolution, built a heterodox socialism, became the world’s largest economy and factory, and in recent years, a hub for high-tech development.

There are objective reasons to believe that the gesture is in good faith. Not only because China insistently affirms its preference for the Global South, but also because, in a certain sense, it needs to do so. The polarization that marked the Cold War is rearming itself again. Trump sees Beijing as his number one target. Europe bows to the US, even though it is despised. Trade and ideological barriers against China are being erected on both sides of the North Atlantic. The choice for the old “third world” is, above all, pragmatic.

Under what conditions could such a partnership occur? In the Brazilian case, this article explores possibilities. These involve the Amazon rainforest, the internet, overcoming the dollar’s weakness, industry, and defense, among other points. But it is, in essence, an invitation to include this topic on the country’s agenda for debate. Since World War II, alliances with Washington have been seen in Brazil as natural and almost unavoidable. Is there any harm in considering other paths, now that the Donroe Doctrine weighs heavily on us? Will we adopt the same stance as the “permanent visa crowd”?

Candid Imperialism: Trump, Racketeering and Venezuelan Oil

It usually takes archival digging, the golden gaffe, an ill-considered remark, and occasional spells of candour by those in power, to admit that the United States has, in common with other imperial powers, brutal ambitions. An example of the latter was General Smedley Butler, who, at his death in 1940, had become the most decorated Marine in US history. After retiring from active service, he was frank about his role. Professing to be a “racketeer” and “gangster for capitalism”, he went on to explain how: “I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Boys to collect revenues in. I helped the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street.” That was just a selection.

With President Donald Trump in power, we do not need a Butler to give the game away or expose any frightful cabal. The empire is out of the closet, bolshie, bright, and more thieving than ever. While the Donroe Doctrine is intended to reprise the Monroe Doctrine, it offers nothing more than imperial rapacity, seizure under pretext. The January 9 meeting with two dozen oil executives at the White House to discuss the fate of the Venezuelan oil market showed Trump to be in full flight as cocky pip and proud procurer of corporate thieving under the cover of government protection.

Representatives from such veteran behemoths as ExxonMobil and Chevron were present to listen to calls from the president that they invest handsomely in modernising and tidying up Venezuela’s tattered oil infrastructure. Problems with the oil itself – heavy, hard to refine, and packed with sulphur, not to mention the questionable number of proven reserves – did not blight the conversation. “American companies will have the opportunity to rebuild Venezuela’s rotting energy infrastructure and eventually increase oil production to levels never seen before,” he crowed at the start of the meeting. Our giant oil companies will be spending at least $100 billion of their money.” In the course of this merry investment, Venezuela would “be very successful, and the people of the United States are going to be big beneficiaries.”

The choice of companies involved in the venture would, however, not be determined by free market wiles or any invisible hand. “We are going to be making the decision as to which oil companies can go in, which we will allow to go in.” They would mostly be American, naturally. Forget the Venezuelans, he insisted. “You’re dealing with us directly. You’re not dealing with Venezuela at all. We don’t want you to deal with Venezuela.”

Jeffery Hilderbrand of the oil and gas producer Hilcorp Energy, and noted Trump donor, was all salivation and gratitude. He was also pleased with the implausible alibi Trump had offered for controlling and pilfering Venezuelan oil for American interests: finding imagined enemies who might do the same thing. “Thank you for your great, tremendous leadership in protecting the interests in the Western Hemisphere,” he sighed with oleaginous gratitude. “The message that you have sent to China and our enemies to stay out of our backyard is absolutely fantastic… Hilcorp is fully committed and ready to rebuild the infrastructure in Venezuela.”

CEO Bill Armstrong, of the Armstrong Oil and Gas company, also smacked his lips at the plunderous prospects. “We are ready to go to Venezuela,” he declared. “In real estate terms, it is prime real estate. And it’s like West Palm about 50 years ago. Very ripe.” Fracking executive and Trump supporter Harold Hamm was tickled by the prospect of adventure, seeing Venezuela as little more than a playground to roam in and profit from. “It excites me as an explorationist.” The country was “exciting” with its abundant reserves, posing “challenges and the industry knows how to handle that.”

Chevron, which already has a presence in the country in partnership with the state-run oil company Petróleos de Venezuela SA, accounting for 240,000 barrels per day, expects to bolster its production by 50% over the next 18 to 24 months. Those at Repsol are dreaming of tripling the current daily production of 45,000 barrels over the next few years, provided the conditions are appropriate.

Not all the oil companies expressed the same level of glowing confidence. Naked plunder comes with its challenges and logistical tangles, not least the touchy issue of Venezuelan sovereignty. Exxon CEO Darren Woods was, for instance, concerned that much would have to be done to make Venezuela an appropriate recipient of capital. One way was to ensure that whoever was in control in Caracas would be eternally reliable and amenable to US oil interests. “We have had our assets seized there twice and so you can imagine to re-enter a third time would require some pretty significant changes from what we’ve historically seen and what is currently the state.” As things stood, given “legal and commercial constructs and frameworks in place”, Venezuela was “ininvestable”.

That same day, Trump further confirmed the choking of Venezuela by signing an Executive Order to prevent “the seizure of Venezuelan oil revenue that could undermine critical US efforts to ensure economic stability in Venezuela.” The Order prohibits US courts from seizing revenue collected from Venezuelan oil and any relevant holds in US Treasury accounts. The customary, absurd justifications follow: to lose control of such funds would “empower malign actors like Iran and Hezbollah while weakening efforts to bring peace, prosperity, and stability to the Venezuelan people and to the Western Hemisphere as a whole.” Were these funds to be tampered with, US objectives to stem “the influx of illegal aliens and disrupting the flood of illicit narcotics” would be compromised.

As for those befuddled figures of the Venezuelan opposition thinking that much of their country’s oil revenue will find its way into the coffers of Caracas, they had best think again. “Putting America first,” as the Order makes clear, means just that. The Venezuelan people don’t count, except as props in tawdry oratory.

No comments:

Post a Comment