Keynes Meets Trump In A Fractured World – OpEd

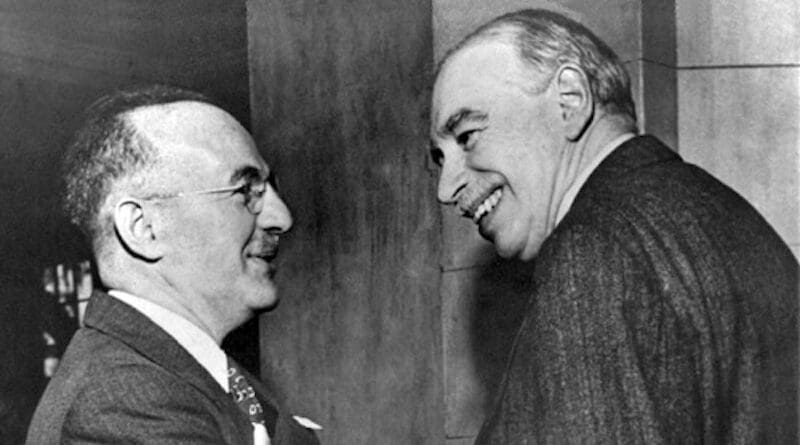

John Maynard Keynes (right) and the US representative Harry Dexter White at the inaugural meeting of the International Monetary Fund's Board of Governors in Savannah, Georgia in 1946. Photo Credit: International Monetary Fund, Wikipedia Commons

Since Covid-19, the World economy has been going through cycles of ups and downs and the roads are still bumpy. This is because the world economy is not only war-ravaged but also having geo-economic disturbances due to emergence of new geo-politico- economic shocks disrupting the recovery by unexpected changes thanks to ‘Animal Spirits’ driving exuberance of ‘irrational sentiments or self-fulfilling prophecy”. It’s the ripe moment to conjure the valuable lessons from the ‘Father of Modern Macroeconomics’, John Maynard Keynes, emphasizing the role of effectiveness of government policy. Why now? That’s because next week on June 5, it is his 142nd birthday.

The source of the problem lies as much in politics as in economics. And, now apart from continuing Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Palestine war in Gaza, another war of different nature is plaguing the economy in a post-pandemic world. That is the Tariff War waged between nations such as, big players like China, EU, Canada, India, South Korea and the US led by second term of Trumponomics due to rise of sentiments for mercantilism and protectionist policies as it was during the Great Depression in 1930s when Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. It was to protect or shield domestic employment and production and was pursued more by business houses than sensible economists at that time. The result was protracted depression as—thanks to reciprocal retaliatory tariffs–trade nosedived as demand evaporated.

The story is different now from that time as the world is facing turbulence, fragility and security issues are serious even though globalization has spread its wings. Global Value Chain, Global Production Network and fragmentation via supply chain, and flow of people and ideas have gripped us unlike in the 1930s when it was not the golden age of globalization. Keynesianism was born out of this crisis as panacea to overcome the downturn. Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ was the brainchild of this idea of this Great Thinker. During 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis, we saw the return of the master—after the short stint of pause during late 1980s—90s–as Keynesian policy’s effectiveness was felt once more to revive the world economy from the systemic crisis of food perils, financial debacle, and climate change.

However, right at this juncture, the master stroke of Keynesian policy is utterly necessary. I discern this policy-dilemma as tax versus the tariffs, the former is in the domain of economics while the latter is more political with economic fallouts as trade relations between nations in a globalized world are crumbling with the spread of unilateralism at the expense of liberal multilateralism. Taxing ‘low’ is a popular expansionary policy a la Keynesian multiplier effects provided budget deficits are not too high to create savings shortage or deficit. Imposition of high escalating tariffs is—according to current policy stance in the US—for compensating that deficit. It is apprehended that extremely high reciprocal tariffs will hurt many businesses including the SMEs, MSMEs as import and exports both are affected by demand-crunch as well as supply-shortage causing voluntary recession resetting trade (VRRT) with a much higher tariff rate of 3% in 2018. This setback is due to uncertainty for consumer spending decisions and setbacks for business planning. Slowing down of the US economy due to this tariff war ripples through the South Korean economy as well as for others, viz., India, China, Central Asia, etc.

When Axel Leijjonehufvoud wrote his famous “Keynes and the Classics”, the argument was to rebuff Say’s Law—’Supply creates its own Demand’. Now, it seems that despite ‘glut’ both sides of the scissors that economists are used to hold—Supply and Demand–needs sharpening, as two sides are blunt by razor’s edge problem as both Supply and Demand are on the verge of collapse. Keynesian policy — couched as effective demand management via a working model by Hicks-Hansen in 1937–calls for revamping demand to induce businesses to supply more so that weakening demand, rising unemployment and retrenchment are overcome. However, the role of tariffs for protecting real wages and domestic employment and production—known famously as Stolper-Samuelson (later winning Nobel in Economic Sciences)—is well-known.

Keynes himself was in favor of tariffs as expounded in his 1933 “National Self-Sufficiency” insofar as it does not go too high to exacerbate demand via rise in cost of living, inflation and prices. To quote him: “I sympathise, therefore, with those who would minimise, rather than with those who would maximise, economic entanglement between nations. Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.” With recommendation of 15% on manufactured and semi-manufactured goods, and 5% on all foodstuffs and certain raw materials, Keynes was more in favor of promoting trade–balancing economic internationalism with mutual benefits to the trade partners’ national objectives—national objectives contributing to global welfare after Great Depression.

However, despite full-fledged globalization and spread of supply chain and MFN clause—unlike Keynes’s time—the current spate of high tariffs fluctuating from 10%, 25% to 100% exorbitantly high prohibitive tariff escalation is detrimental to the world economy’s predicament. This acts counter to Keynes’s idea of marginal propensity of consumption of any goods when countries engage in trade with respective comparative cost advantages. Demand is severely affected as high tariffs causing higher prices has slowed down spending in USA, EU, major emerging markets, including in South Korea with unstable inflation and unsteady unemployment. This is what not Keynes—had he been alive-would have recommended as these dampen consumers as well as investors’ sentiments esp for the middle-income earners. With reciprocal tariff threat—as we see in East Asia and other nations including in the USA—price hike concerns are causing macroeconomic turbulences, core inflation, and CPI.

Now unlike in the Keynesian era, these pass-through effects work with direct and indirect effects via engagement in the supply chain where trade in imported intermediates dominates production and supply. We see weakening demand for export-oriented economies like S. Korea where semi-conductors, cars and consumer goods are suffering from demand-switching and spending crunch. Not only shifting away from US products is happening, as we see in EU and other nations, also substitution for homespun goods for foreign goods are occurring with severe supply shock. Hence, Keynesian demand crunch channel is manifest as a supply debacle as well. This is the beauty and relevance of Keynes and his idea of “Animal Spirits’ where unanchored expectation of inflationary spiral and deflation, interest rate could further squeeze the global economy.

If we think about East Asia, as China is part of these reciprocal tariff games, her trade partners—South Korea and Japan—are not immune to this ricochet effects as regional supply chain or value chain will cause chain reaction of cascading effects although the economy. Particularly, in case of S Korea, as a major trade partner of the United States and China, the trade block will cause demand and supply shocks as markets are rattled through cost-push and demand-pull effects affecting internal demand.

On top of that the presidential election is knocking at the door with lots of uncertainty about stability of government and hence, policy effectiveness. The election is crucial on two grounds: in terms of appropriate trade, industrial and labor policy as well as balancing geo-political competition with internal snags. In case of Korea, a three-pronged crisis is plaguing the economy: political instability with forthcoming national election knocking on the door (June 3, 2025), demographic decline for past several years with no light so far at the end of the tunnel, and fragile domestic security along with geo-political tension.

On top of these trilemma, the dilemma of balancing economic allies with China and USA is emerging as a grave concern with losing comparative advantage in major technology-intensive sectors and excessive past dependence on export-biased growth. Exports are expected to fall by 3.7% in May due to a fall in chip demand. Korea needs to reconsider strategic alliance with India (as a trade partner with huge domestic market and thriving democracy), Japan, as well as investing in frontier technologies, such as, AI, Green Energy, Electric vehicles, and medical tourism via digital health care, to name a few.

In fact, if AI and emerging technologies are used via extracting value from ‘big data’ to deliver ‘social goods’ to the needy people, then that would help sustain the multiplier effect under fiscal or monetary policy. In other words, alongside the Keynesian demand management Korea as well as other emerging nations like India need to take advantage of the cutting-edge technology, build a manufacturing sector which could generate job, boost growth, and participate in the GVC in the process. This could sustain the demand side boost-up as spillovers form both sides would—as a symphony of harmony of different tunes—conjointly deliver the desired objectives. Any elected new government needs a viable alternative that helps Korea and the world economy to escape from the root cause of current economic, political and social malaise.

What is the role of the Government? The role of a conductor in an orchestra is to orchestrate the movement of rhythms or pulses of different instruments of fiscal and monetary policy. As Mazucatto said, role of entrepreneurial state is necessary to unbind the ‘Prometheus’, not Leviathan. A new cohort of entrepreneurial talent needs to be developed for serving dual purpose –creating new jobs, formalization of informal economy, structural transformation as well as generating demand via job creation, and new sources of development.

A poster child, Korea needs revamping its policy tools. Because of tariff war, the Korean industry has one of the worst situations with labor market disruptions. The government should prepare for the risks, and the government has to make some social insurance, so the risk of unpredicted catastrophe is hedged.

Semblance of normality is possible only with great caution, vigilance, and removal of abnormalities of policy management crippling the economy. The casualties of all these “wars” and wrong policy are divisiveness, trust in the illiberal democracy, centralization of power, waning consumer confidence. Fall in investors’ confidence slackening investment rate is retarding the growth. Wrong politics and motley of inappropriate policies is unholy muddle. Keynes in The End of Laissez Faire (1926, 46) said: ‘The important thing for Government is not to do things which individuals are doing already, and to do them a little better or a little worse; but to do those things which at present are not done at all.”

The government needs to boost the economy a la Keynes. To boost, we need a ‘Gardener’ mechanism so that supportive measures like removing weeds to nurture the trees, through managing in multiple dimensions as mentioned above. For that we need vision, transparency, accountability and moral compass, not narrow parochialism based on divisiveness. Institutions curbing authoritarianism and enhancing efficacy of policy implementation via decentralized decision-making is important. Crisis plans need to be clear headed. Otherwise, any business or venture will collapse without diagnosis of the disease. As Julius Caesar said: “the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings” –to create—as per Adam Smith–‘a tolerable administration of justice’. Lord Keynes is really ‘Baack!’ We should wish him a Very Happy Birthday to steer the right path out of crisis for the global economy.

Gouranga Gopal Das

Gouranga Gopal Das is Professor of Economics at the Department of Economics, Hanyang University, South Korea. Prior to this appointment, he worked as a Visiting Professor of Economics at Kyungpook National University, Korea and as a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the University of Florida. He obtained his M.Phil and PhD in Economics from Jawaharlal Nehru University, India and Monash University, Melbourne, Australia respectively. He has been a visiting researcher in the International Monetary Fund (IMF), University of Antwerp, Belgium and UNU-World Institute of Development Economics Research at Helsinki. Primary fields of his research focus on Trade and Development, Computable General Equilibrium Modeling, Technological Change, Outsourcing. He has published widely in journals such as World Economy, Journal of Policy modeling, Journal of Asian Economics, Journal of Policy Reform, Technological Forecasting and Social /change, Books from Springer Nature and Cambridge University Press among several others. Recently he has been awarded the Editor of Distinction Award 2025 by Springer Nature.