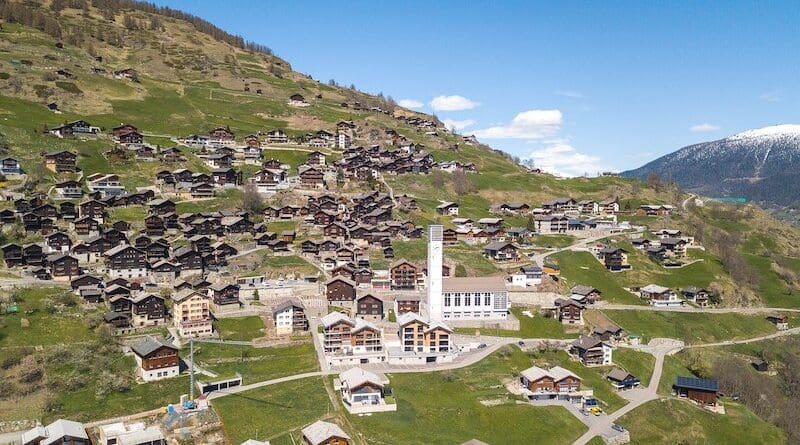

Törbel is a small Swiss mountain village that has attracted the attention of international scientists. Their findings on how mountain farmers utilise water and pastures are shaping the way science addresses collective digital resources today.

By Benjamin von Wyl

In 1483, Swiss farmers who lived in a mountain village concluded a contract on water and pasture utilisation. This has proven so sustainable that open-source advocates from the Mozilla Foundation, known for its web browser Firefox, today want to apply the same principles to shared digital resources, or what are called “digital commons” today.

How did this come about?

Large meadows and forests in many regions of modern-day Switzerland have been managed collectively by local populations for over 500 years. In mountain regions in particular, these corporations and communities still manage common agricultural areas, known as Allmenden (in German), according to clear rules and sustainable principles.

Farmers did exactly this for centuries in the southern Swiss Alpine village of Törbel in canton Valais. Törbel is famous among scientists not least because of the 1483 treaty.

Why an anthropologist headed to a Swiss mountain village

One expert called it “the over-researched village” when speaking to Swissinfo. Scientists from Zurich were the first to show an interest in Törbel. But in 1970, the American Robert McC. Netting arrived. “Why is an anthropologist and Africanist going to Alpine Switzerland?” He was often asked this question, according to his book, Balancing on an Alp.

In the ten years between his first visit and the publication of his book, Netting spent about one and a half years in the village, but also “one summer in a windowless university office”, where he filled index cards with the data about the lives of those who had dwelt in Törbel over the centuries.

The “village universe is not very big, even if you extend it to three centuries”, he writes in Balancing on an Alp. This manageable cosmos was one of the reasons why the Africanist, who had previously researched the Kofyar in northern Nigeria, was drawn to Törbel. Netting was interested in how a small-scale farming community forms an ecosystem with its environment.

His book describes many facets of a fairly homogeneous community. In Törbel, Netting says, for at least the last seven centuries “there was no resident aristocracy or landowning class, only a few full-time craftsmen or merchants, and no recognisable group of landless workers”. It was purely a farming village.

Women from the outside could marry in and become villagers, but the priest was always an outsider, Netting reports; even political orientation was passed down from father to son in the Törbel microcosm. Netting was interested in many aspects of community life. But above all, his research showed how the people of Törbel lived with their environment and practised agriculture, in which common land played a major role. Since the treaty of 1483, the collective use of meadow, forest and water channels was clearly regulated.

Elinor Ostrom and her principles for common goods

This also awakened the interest of Elinor Ostrom, a political scientist. Ostrom was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. In her work, which was published in 1990, the American developed criteria for the successful management of common goods.

Törbel is the first, fundamental case study in her book. Ostrom also scrutinised Japanese mountain villages, Spain and the Philippines. Everywhere she went, she discovered systems through which communities found a sustainable way of dealing with common goods – be it with millions of hectares of land in the villages of Hirano, Nagaike and Yamanaka, or the water court of Valencia.

Ostrom wrote in 1990 that analysing case studies could provide a deeper understanding of how people shape “situations within which individuals must make decisions and bear the consequences of actions taken on a day-to-day basis”.

Her research has given the tradition and lore of Törbel a place in the world. It has made the people of Törbel bearers of knowledge that could make living together better elsewhere.

Before that, the consensus was that if several owners farmed the same property, everyone wanted to maximise their share, and they would thereby overexploit the common property. However, Ostrom derived principles from her research that prevent common goods from being exhausted and the “tragedy of the commons” from taking its course. These include clear boundaries between users and non-users of the commons, as well as harmonisation with local social and ecological conditions.

Rural corporations, urban cooperatives

Törbel is a rural community. According to the historian Daniel Schläppi, however, these communal corporations have more similarities with left-wing, urban co-operatives than either side realised – at least until Olstrom’s research was published.

It is not only the open-source advocates of the Mozilla Foundation who are committed to collective resources on the Internet and studying Ostrom’s findings, but also the International Cooperative Alliance and, with it, co-operative enterprises all over the world.

‘Pillars of Switzerland’

Ostrom’s principles were recently called “pillars of Switzerland” by Swiss Environment Minister Albert Rösti.

In May 2025, the agronomist and politician from the right-wing conservative Swiss People’s Party spoke at the Association of Swiss Corporations about Törbel and how it had served as a model for the conditions under which communities with collective property can function.

Rösti drew a comparison between the clear rules demanded by Ostrom and the Swiss constitutional state. He linked these “clear boundaries” with “sovereignty and independence”. The way communities organise themselves and make participatory decisions aligns with direct democracy in Switzerland, he said. The fact that local circumstances are taken into account is what “we call federalism”, the minister said.

Corporations are still an important player in the modern economy, but they have also shaped the “principles of our state”, he added. Switzerland would not exist “in its current form” without the “long history of corporations”.

The openness of the people in Törbel

Another reason these “pillars of Switzerland” have become part of world science is that the people of Törbel were open to scientists 50 years ago. Netting was a “devoted friend to us simple mountain dwellers”, said a letter from Törbel to Netting’s wife.

For Ostrom, the village held a big reception in 2011. The economist Bruno S. Frey, who still finds Ostrom’s research groundbreaking today, remembered a “parade with an orchestra through the village” in a conversation with Swissinfo.

It was a special moment for Ostrom, who died in 2012. She told Frey this after the ceremony in Törbel. To date, Ostrom is the only woman to have been honoured with the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Scientists look to the future with Törbel

Today, a new generation of scientists is in the village. Part of a Horizon Europe project in Törbel is currently investigating how rural regions could overcome “depopulation and a growing digital divide compared to urban areas” and become “Rural Innovation Ecosystems”.

Mariana Melnykovych, who heads the project, told Swissinfo that it is the “enduring, well-documented community organisations that are still functioning today” that keep scientists coming to Törbel. She and her team want to work with the same approaches as Netting in Törbel, but also incorporate innovations and the changing climate. Ostrom’s research also played a role in the choice of Törbel.

“Törbel is a small place with a big impact,” Melnykovych said. Researchers would be able to observe here how “rural communities adapt to change while preserving fundamental social and ecological values.”

She and her team are not just looking back into the past. “It’s about finding out how a village rooted in history masters the future, with its people, its knowledge and its intact community assets,” said Melnykovych.