(The Conversation) — Though they lived centuries apart, Aristotle and Tsunetomo both explored what it means to live virtuously, and the risks of wanting praise or recognition.

Desire for validation from other people can lead people toward virtue – or in the other direction. (Jacob Wackerhausen/iStock via Getty Images Plus)

January 9, 2026

THE CONVERSATION

(The Conversation) — Pete Hegseth, the current defense secretary, has stressed what he calls the “warrior ethos,” while other Americans seem to have embraced a renewed interest in “warrior culture.”

Debate about these concepts actually traces back for thousands of years. Thinkers have long wrestled with what it means to be a true “warrior,” and the proper place of honor and virtue on the road to becoming one. I study the history of political thought, where these debates sometimes play out, but have engaged them in my own martial arts training, too. Beyond aimless brutality or victory, serious practitioners eventually look toward higher principles – even when the desire for glory is powerful.

Many times, “honor” and “virtue” are almost synonyms. If you acted righteously, you behaved “honorably.” If you’re moral, you’re “honorable.” In practice, chasing after honor can prompt not only the best behavior, but the worst. We all long for validation. At its best, that longing can motivate us toward virtue – but it can also lead in the opposite direction.

I am fascinated by the way two famous thinkers grapple with this paradox. They are teachers who lived centuries apart, on opposite sides of the world: Aristotle, the Greek philosopher; and Yamamoto Tsunetomo, a Japanese samurai and Buddhist priest.

The ‘prize of virtue’

In the age of Homer, the Greek poet who is thought to have composed “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” around the 8th century B.C.E., being “good” meant attaining excellence in combat and military affairs, along with wealth and social standing.

According to classics scholar Arthur W.H. Adkins, the “quiet virtues” like justice, prudence and wisdom were seen as honorable, but were not needed for a person to be considered good during this time.

Several centuries later, though, those virtues became central to Socrates, Plato and Aristotle – Greek thinkers whose ideas about character continue to influence how many people, both inside and outside academia, view ethics today.

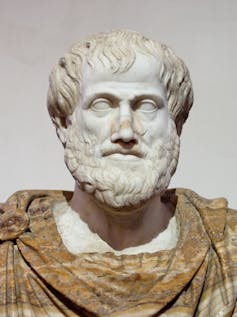

Aristotle’s understanding of virtue is reflected not only in his works, but in the deeds of his reputed student, Alexander the Great. The Macedonian king is commonly held as the best military commander in antiquity, with an empire that extended from Greece to India. The Greek author Plutarch believed that philosophy provided Alexander with the “equipment” for his campaign: virtues including courage, moderation, greatness of soul and comprehension.

In Aristotle’s view, honor and virtue seem to be “goods” that people pursue in the search for happiness. He refers to external goods, like honor and wealth; goods related to the body, like health; and goods of the soul, like virtue.

A Roman copy of a bust of Aristotle, modeled after a bronze by the Greek sculptor Lysippos, who lived in the 4th century BCE.

National Roman Museum of the Altemps Palace/Jastrow via Wikimedia Commons

Each moral virtue, such as courage and moderation, forms one’s character by maintaining good habits, Aristotle proposed.

Overall, the virtuous human being is one who consistently makes the correct choices in life – generally, avoiding too much or too little of something.

A courageous warrior, for example, acts with just the right amount of fear. True courage, Aristotle wrote, results from doing what is noble, like defending one’s city, even if it leads to a painful death. Cowards habitually flee what is painful, while someone who acts “bravely” because of excessive confidence is simply reckless. Someone who is angry or vengeful fights due to passion, not courage, according to Aristotle.

The problem is that people tend to neglect virtue in favor of other “goods,” Aristotle observed: things like riches, property, reputation and power. Yet virtue itself provides the way to acquire them. Honor, properly bestowed, is the “prize of virtue.”

Still, the impulse for honor can be overwhelming. Indeed, Aristotle called it the “greatest of the external goods.” But we should only care, he cautioned, when honor comes from people who are virtuous themselves. He even recognized two virtues – greatness of soul and ambition – that involve seeking the correct amount of honor from the right place.

Loyalty, even in the face of death

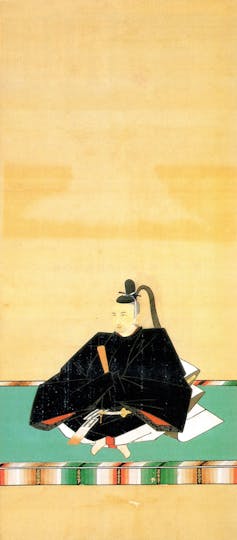

Nabeshima Mitsushige, the 17th-century lord whom Yamamoto Tsunetomo served.

Kodenji Temple Collections via Wikimedia Commons

Two thousand years later, and half a world away, the samurai warriors of Japan also famously focused on honor.

One of them was Yamamoto Tsunetomo – a servant of Nabeshima Mitsushige, a feudal lord in southern Japan. After his lord’s death in 1700, Tsunetomo became a Buddhist priest.

Tsunetomo’s counsel can be found in the “Hagakure-kikigaki,” a collection of his teachings about how a samurai ought to live. Today, this text is considered one of the most notable discourses on “bushidō,” or the way of the warrior.

Tsunetomo’s samurai oath involved the following:

I will never fall behind others in pursuing the way of the warrior.

I will always be ready to serve my lord.

I will honor my parents.

I will serve compassionately for the benefit of others.

The road to becoming a samurai required developing habits that would enable the warrior to fulfill these oaths. Over time, those consistent habits would develop into virtues, like compassion and courage.

To merit honor, the samurai were expected to demonstrate those virtues until their end. Tsunetomo infamously stated that “the way of the warrior is to be found in dying.” Freedom and being able to fulfill one’s duties require living as a “corpse,” he taught. A warrior who cannot detach from life and death is useless, whereas “with this mind-set, any meritorious feat is achievable.”

A courageous death was integral to meriting honor. If one’s lord died, ritual suicide was considered an honorable expression of loyalty – an extension of the general rule that samurai should follow their lord. Indeed, it was considered shameful to become a “rōnin,” a samurai dismissed without a master. Nonetheless, it was possible to make amends and return. Lord Katsushige, the previous head of the Nabeshima domain, even encouraged the experience to truly understand how to be of service.

The Japanese characters for ‘bushidō,’ the ‘way of the warrior.’

Norbert Weber-Karatelehrer via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

NEW: Bring more puzzles and play to your week with RNS Games

The path to virtue, then, might involve a period of dishonor. The “Hagakure” suggests that fear of dishonor should not lead a samurai to mindlessly follow his lord’s instructions. In some cases, a servant could correct their master as a sign of “magnificent loyalty.” Tsunetomo referred to the example of Nakano Shōgen, who brought peace after persuading his lord, Mitsushige, to apologize for not paying proper respect to certain families within the clan.

The “Hagakure” presents honor as something essential to the way of the warrior. But fame and power should only be pursued along a path aligned with virtue – a life in accord with the samurai’s core oath.

“A [samurai] who seeks only fame and power is not a true retainer,” according to the “Hagakure.” “Then again, he who doesn’t [seek them] is not a true retainer either.”

Honor matters in the pursuit of virtue, both Aristotle and Tsunetomo conclude, especially as a first source of motivation.

But both thinkers agree that honor is not the final end. Nor is moral virtue. Ultimately, they acknowledge something even higher: divine truth.

For Aristotle and Tsunetomo, it seems, the way of the warrior turns toward philosophy rather than unrestrained power and endless war.

(Kenneth Andrew Andres Leonardo, Postdoctoral Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of Government, Hamilton College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

The Conversation religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The Conversation is solely responsible for this content.