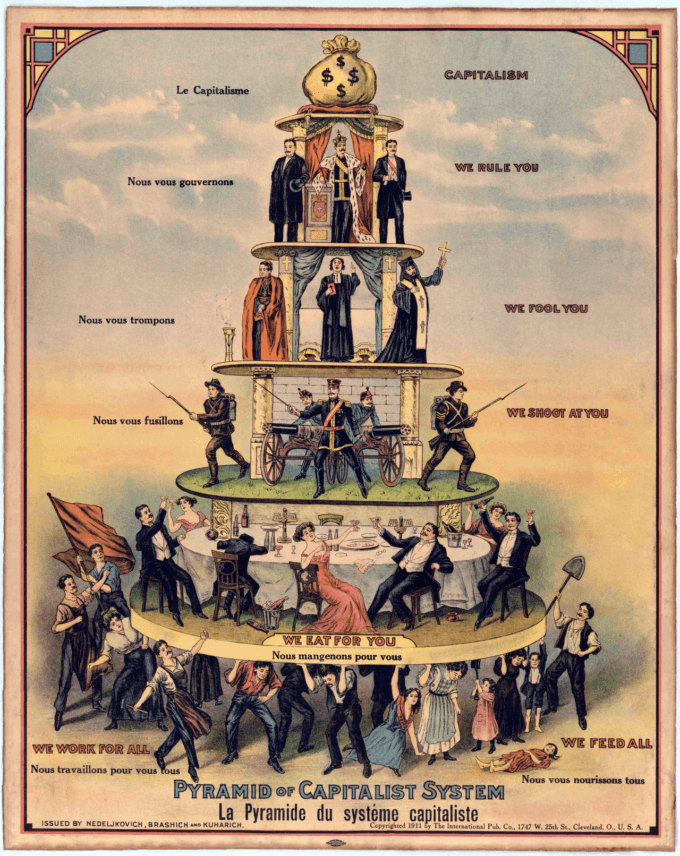

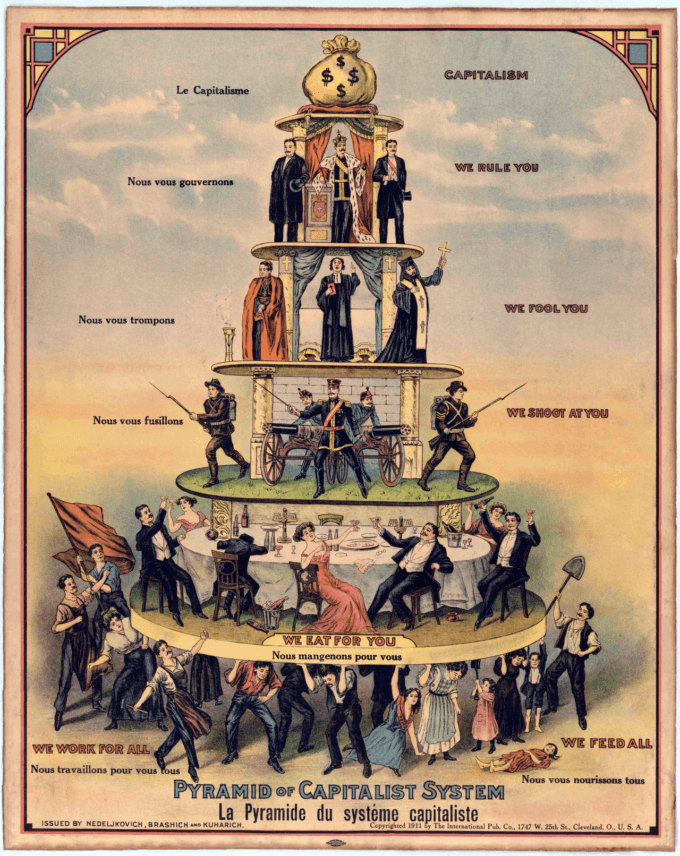

IWW poster printed 1911 – Public Domain

Some thoughts on that majority element of top-quintile US society that persistently refers to itself as “the middle class.”

My friend Peter Phillips has a new book out called Titans of Capital wherein he provides details for who it is, exactly, that owns most of the world’s wealth, investments, property, etc. He also provides details for who manages that wealth. What got me thinking the most was the information on this relative handful of a couple hundred people who manage most of the world’s investments, many of whom are not even millionaires themselves, though all of them are very well-paid, by any reasonable standard

By any way you can measure these things, the class divide is by far the most impactful one on society. There is no demographic that has more money, power, or influence than the rich. Compared to them, every other demographic, however you slice it, is poor. The top quintile is disproportionately both male and white, and the highest reaches of the wealth spectrum much more so, but most white males are not part of it.

I mention this obvious truth here now because it is completely tied up with the false consciousness imbued in the minds of so many Americans, especially within the top quintile. If, as NPR would have us believe, most white Americans are living comfortable “middle class” lives, why worry about them? A good humanist should be concerned about other people — the ones who are suffering, who almost always seem to be, by American liberal top-quintile definitions, LGBTQ and BIPOC.

That is to say, the system is working fine for white people, who make up most of the middle class, which is normative. The poor white people are not normative, they’re an example of an individual failure, or an indication of a crack within a system, which is otherwise working for them. The concerns for society at large, if a person within the top quintile has any, are therefore focused on those who are truly deserving of concern, who are by definition not white. This is the methodology of divide and conquer in the USA that has been deeply inculcated in the minds of Americans of all classes.

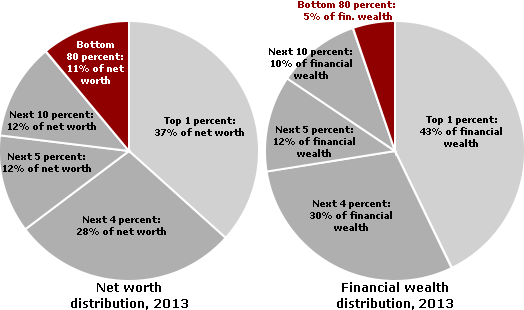

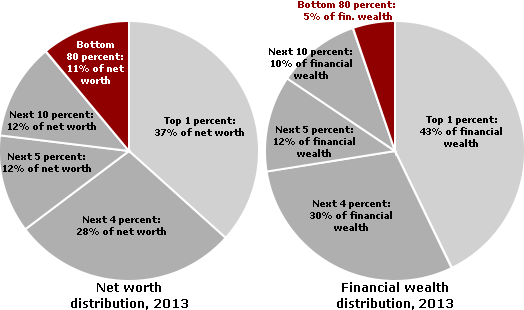

There is much to be said of the ultrarich, the handful of out-of-control billionaires who own half the world’s wealth, and all the destruction and misery they’re causing.

And I know many things will be changing dramatically in the world in the coming years that may especially impact the jobs of anyone whose job can be done from behind a screen, and the ways that will all play out with the rise of AI are still unclear, though it doesn’t look good for white-collar workers of any kind.

But as of today the class setup still exists with its familiar curve, one that skyrockets upwards once it reaches the top quintile of the population, and then skyrockets far faster within the upward reaches of the top 1%. It’s that top quintile I’d like to ruminate on here.

The top quintile phenomenon is striking if you have a penchant for history, and the history of colonialism in particular. If you look into it, you’ll find in this history a common strategy on the part of the colonizing power to govern the colonized society in such a way that the top 15% or so of the population is privileged economically, socially, and politically. This is the 15% of the society from whose ranks come those who will run the colonial show on behalf of the colonizing power. The colonizers ran things according to this principle from India to Iraq.

Knowing about this history, it’s striking to see that graph of how wealth gets more and more concentrated, particularly within that top quintile, in the US today, as with countries like Mexico and Brazil, where the same kind of phenomenon can be observed.

Who is in that top quintile in these societies? What do they do? How does being in the top quintile affect their outlook personally and professionally? How does this impact the rest of us?

I don’t think you have to look much past the history of colonialism to answer these questions, because they’re the same as they always were. As in the colonial days, the top quintile runs everything.

Within this quintile you will find the politicians, most of the experts, the scientists, the lawyers, judges, those who run the universities, the banks, the real estate management companies, the corporate media outlets, the military generals, the chiefs of police, the owners of the apartment buildings, the owners of the trailer parks, most of the “mom and pop” landlords, and so many others.

Having grown up among this top quintile set in the US, I have spent my adult life both inside and outside of top quintile reality.

Something that regularly hits me is how effective the propaganda we all grew up with in America about this “middle class” stuff has been. Growing up in Wilton, Connecticut, everyone claimed to be part of the middle class. A generation later as a parent with a child who, largely due to her French citizenship, like me, went to school with the children of the elite — I went to school with the mayor’s son, my daughter went to school with the mayor’s daughter — I find nothing has changed. Those who live in spacious suburban homes with household incomes well into the six digits overwhelmingly still call themselves “middle class.”

They’re not, of course. They’re in the top quintile. Top Quintilians? Maybe there’s a better term. But certainly not “middle” in terms of either wealth or income.

Where I grew up, the vast majority of kids graduated from high school and then went to college. I still find it shocking to look up the statistics and see that less than a third of Americans over the age of 25 have a college degree. I don’t either, but growing up in Wilton, I thought that made me extremely unusual, and something of an abject failure at life. But apparently I’m perfectly normal.

Where I grew up, it would be normal to hear kids say something like, “almost everybody goes to college.” In Wilton, this appeared to be true. They may perhaps on occasion watch the news or read a book, but what mainly succeeded in shaping their worldview was growing up in Wilton, it always seemed to me.

And the people who grew up in places like Wilton are the ones who go on to run the country, as well as the ones who go on to become the pundits on TV telling us how well or how badly they think it’s being run.

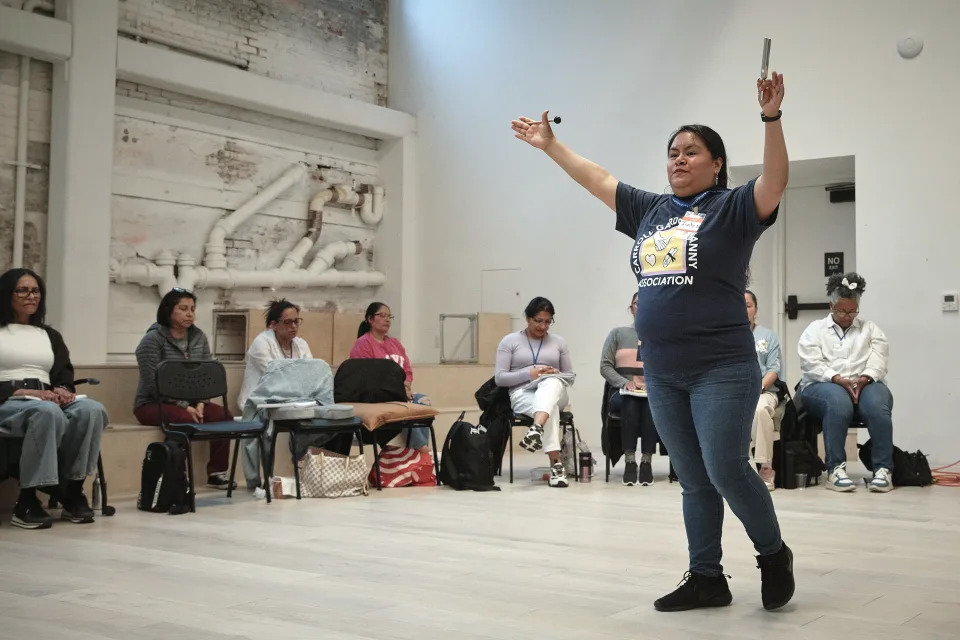

I have friends and relations with members of the top quintile in other countries, like in Mexico, and India, and Lebanon, where in that segment of the population you’ll commonly hear people say things like “everybody has a nanny.”

I feel compelled to ask people if the nannies also have nannies. And among the kids I grew up with in Wilton, I want to ask why are the bus drivers always people who speak Spanish and don’t live in our town? Where do they come from? Did they go to college? Do they also have families, and kids? Where do their kids go to school? Not in Wilton. Will they be going to college, too?

When you live among the top quintile, most of the people you know are also top-quintile people. The bus drivers and the nannies are the minority, and we’re providing them with much-needed jobs, even if they can’t afford to live in our town or send their kids to our schools.

If “middle class” were just a euphemism and everybody knew that that was the case, and that it had nothing to do with the middle of anything, then maybe it wouldn’t bug me so much. But I know these people, and I know that in their minds, their lives are average — because for them, with almost everyone they know being fellow top-quintile people, their lives are average, and they feel very much in the middle. The middle of somewhere, anyway.

The people living comfortable lives in the top quintile, sadly, are not the middle, however. The bus drivers and the nannies are actually the vast majority of society.

Most of the bottom 80% don’t live in, work in, or visit the affluent, polished suburbs the top quintile mostly live in, so they’re not particularly visible as the vast majority, but people who live lives more along the lines of those nannies and bus drivers are, in fact, the vast majority.

Of course that means if you’re in the top quintile and you’re talking to your neighbors, your friends, other parents at the local school, etc., you’re going to be talking to people where, for example, the vast majority are homeowners, and very few are renters. Most of the homeowners won’t themselves be landlords, but a significant minority of them will be. In fact, the vast majority of “mom and pop” landlords in the country are in this top quintile.

If you’re a politician living in a neighborhood like that, which is where they mostly live, even if you’re truly interested in the welfare of your fellow people and thus you’re asking your friends and neighbors about their concerns, those top quintile homeowners and “mom and pop” landlords, those 6-figure-earning neighbors are unlikely to be listing the urgency of rent control as a top issue. They’re unlikely to be too concerned with more state or federal funding for the schools, which in their town are doing just fine — and if they’re not, then the expense of private school is already enough to be spending money on, without a rise in taxes to pay for public schools many of your neighbors are not using.

As I travel I meet people from, for example, Chile, who will earnestly and honestly talk about the economic miracle that took place in that country under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. These are people I meet randomly, in an airport or someplace, not people who know me.

This used to shock me, knowing what I already knew about how Pinochet’s rule greatly benefited the top 10% of Chilean society, while impoverishing most of the rest of it.

But if you’re part of that top 10%, hell, that’s a lot of people, your fellow top 10%ers. Even in Chile, that’s a lot of people — two million or so, at its current population. Whether you’re in Santiago or Mexico City or Portland, Oregon, it is exceedingly easy never to go to the neighborhoods where the 80% live, or have much of anything to do with the people who live in them, unless it’s because the highway goes through that neighborhood, or you’re stuck at a red light somewhere, or if you go out to eat and you have a brief interaction with your server, or because you have a nanny.

Thinking of the top quintile issue in relation to the current gutting of the federal bureaucracy, a couple points come to mind that seem relevant, in terms of different reactions to the whole situation from different elements of society.

While there are all kinds of federal workers being fired in the ugliest of ways, those project managers, scientists, and IRS revenue officers are in the top quintile. Most of the rest of the federal workers are, too, if they’re in a two-income household.

If you live in a peaceful suburban neighborhood or an upscale urban enclave, these mass layoffs are happening to your neighbors. If you live in a Class C apartment complex next to a busy road, likely not.

If you live in a top quintile suburb, not only are some of your neighbors losing their jobs, and having their lives and the lives of their families upended, but most people in the neighborhood previously had relatively positive experiences with government. For them, the schools are pretty good. In their town or neighborhood, the trash gets picked up reliably, the water supply is clean, the facilities in the public parks are well-maintained, and the roads are repaved regularly. For them, if they call the police, the police come to help, with an assumption that the person in the suburban house calling for help is the one who needs help, not whoever else might be involved with the situation.

So for them, the idea of tearing apart the federal bureaucracy seems even crazier than it does to most people.

While there may be many people concerned about what’s going to happen to popular institutions like Social Security and Medicaid, judging from what’s going down on the streets, there is not a massive groundswell of people from the bottom 80% who are horrified by what DOGE is doing (or horrified by the idea of peace talks between Russia and Ukraine, for that matter). I’d surmise that this lack of widespread opposition is due to the fact that for people who aren’t living within the top-quintile bubble, their experiences with government have been largely negative.

For them, taxes are always too high, on wages that are always too low. Housing is generally precarious, skyrocketing in cost, especially in the past 20 years or so, with no effective intervention on that impossible trajectory from any federal or state legislature. The schools in the neighborhoods of the bottom 80% are understaffed and overcrowded. The streets are often full of rubbish, which gets worse every year, as the housing crisis worsens. When people need help, there so often doesn’t seem to be a solution forthcoming from any element of the bureaucracy. This is how they experience government.

Whatever the way forward for any of us may be, it probably will need to involve collectively coming to terms with the class reality of it all. And in reality, the top quintile is not the middle class, in the sense of being a class that’s in the middle, between the poor and the rich, as if society were a Bell curve. US society isn’t a Bell curve. It’s a steep mountainside that climbs upwards almost vertically as it rises. The top quintile owns the vast majority of it all, with a tiny handful of them owning around half of what the rest of the quintile owns. And collectively as a quintile in one role or another they run everything, basically on behalf of the stockholders — or was that the stakeholders? No, that’s a euphemism. The stockholders, particularly the biggest of them.

The top quintile may not be a middle class. But it is very much in the middle, in the sense of being between the rich and the struggling majority, a buffer class that keeps the whole top-heavy house of cards from collapsing. It may be normative for many or probably most of the top quintile people to believe they are the middle class, and normative for so many of the other 80% of society to aspire to be part of this fantastical middle class, to pretend they already are in it, and to feel inadequate for failing to be in it.

Either way, the widespread belief that this top quintile is this thing called “the middle class” is both a necessary delusion for the maintenance of domestic tranquility, such as it is, and one that needs to be overcome by both the top quintile as well as by the rest of society, if we have any hope for forward motion in this country.

If people within or not within the top quintile believe the top is the middle, then this is no different from believing 2+2=5. It’s not real, it doesn’t make sense, and it skews reality for everyone involved with this collective fantasy. Who owns our world? Who runs it? Who is on top, who is in the middle, and who is on the bottom? If we don’t have a concrete, broad agreement on the answers to these extremely basic questions about society, how can we conceivably begin to address the massive problems with this whole setup? I don’t think that’s possible. But another world is.