Kathy Johnson | Posted: July 7, 2021

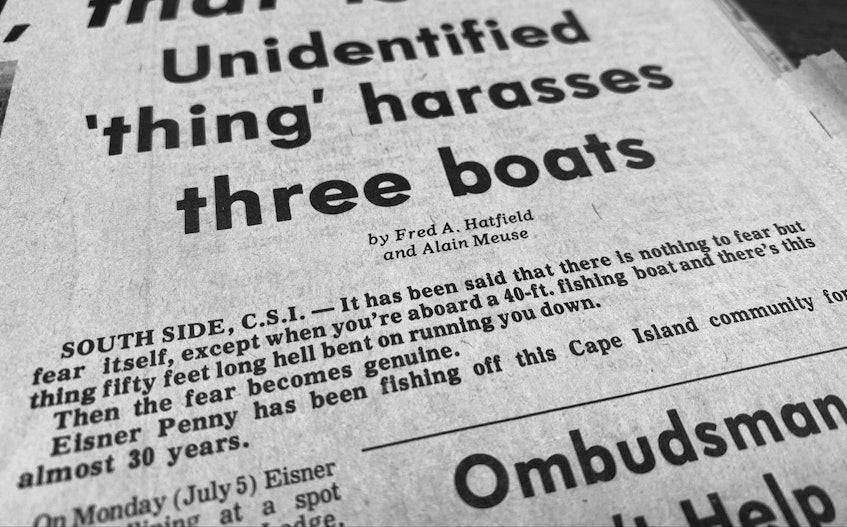

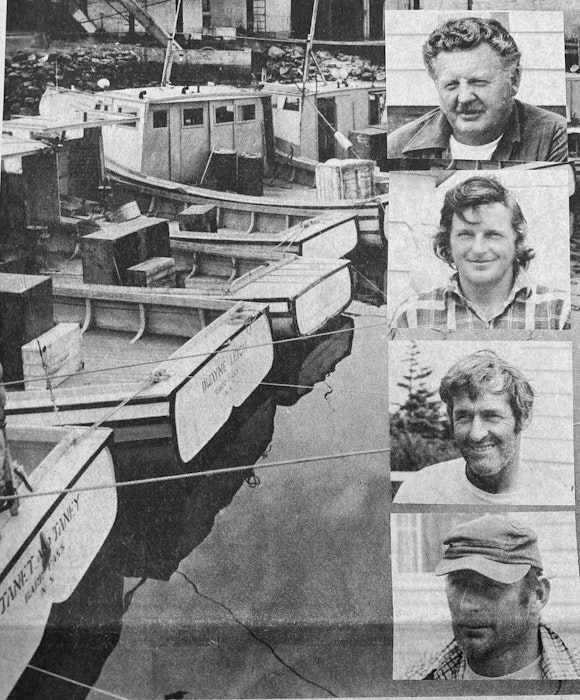

CAPE SABLE ISLAND, NS – It was 45 years ago, between July 5 and 9, 1976, that five Cape Sable Island fishermen fishing off southwestern Nova Scotia on three different boats, on three different days, had encounters on the same fishing grounds with a sea creature unlike anything they'd seen before.

It’s certainly an experience 69-year-old Rodney Ross has never forgotten.

He's the only fishermen of the five still alive.

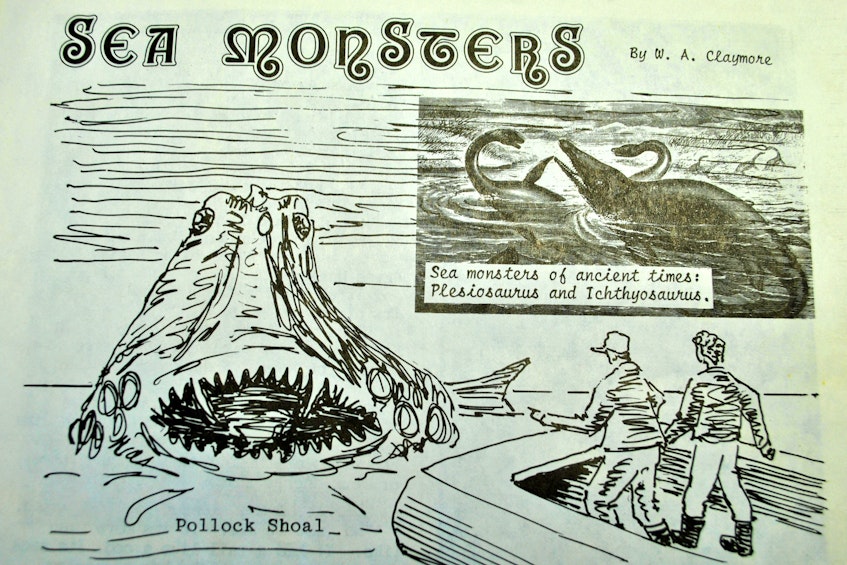

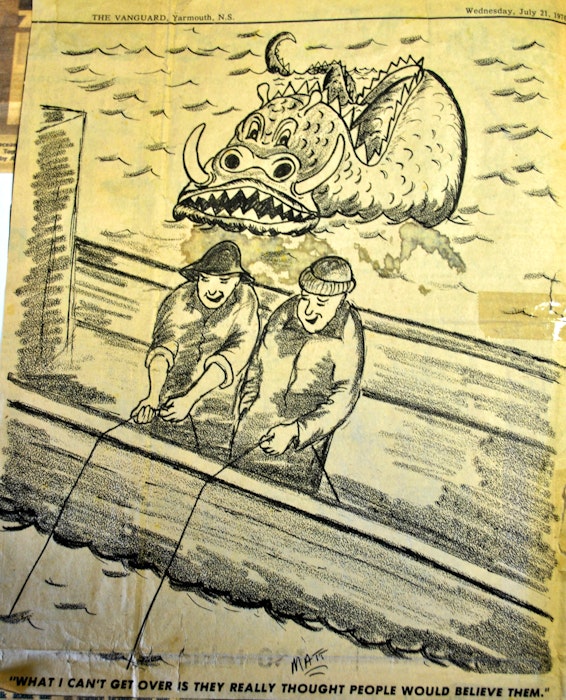

1976 story in the Yarmouth Vanguard. - File Photo

The encounters

The late Eisner Penney was the first to have an encounter – on July 5, 1976 – when fishing on Pollock Shoal, about eight to nine miles off the southern coast of Cape Sable Island, recalls Ross.

“Eisner seen it on a Monday,” Ross says. “When he got done fishing he was headed home and noticed this thing chasing him was out of the water, probably 10 to 15 feet out of the water and it chased him three, four miles or more and kept picking up steam. He didn’t lose it until he got into real shoal water – what we call the horse race – and it went under.”

When Ross set sail with his father Keith for Pollock Shoal two days later, they were unaware of Penney’s encounter.

“We went there Wednesday," he says. "We were fishing, doing pretty good, the tide started to go, so dad went down in the cud to get something to eat.”

Ross continued fishing on the deck. Back then they hauled by hand. No machines. He was getting one or two fish every sound.

But then, he says, it was like everything died.

"The gulls disappeared. The hags disappeared. I made three or four sounds, but nothing," he says.

"I could hear this noise like a swishing noise. It was thick fog . . . I seen this black thing coming through the water. It was like a hump, three or four feet out of water – this hump with two big eyes."

What is that?

At first he thought it was a sunfish and called to his dad to come out and see what he thought it was. He peeked out and said, "sunfish," but when the thing came back seconds later, his father didn't know what to think.

"He realized it wasn’t a sunfish. We watched this thing 15, 20 minutes. It would swim down by, pretty near go out of sight, swim back up to the westward and not one time would it look at us. It never went under. A whale, you can hear them a mile away. Not once did this thing blow."

"It was like it was ignoring us except for this one time. He turned and was looking right at me.”

Ross estimated it was about 70 to 80 yards from the boat.

“Dad went up and started the engine. We knew something was going to take place. It started coming for the boat. It kept coming, rising out of water. The last of it – it was about 15 feet out of water and opened his mouth. He was coming aboard. He was after me," says Ross.

"Dad waited until it was about 15, 20 yards away and opened it wide open and we shot ahead. I ran up underneath the house, turned and looked and could see this big body come out of water. He just clipped the stern of the boat."

"This thing meant business. If we had sat there, we would have been gone. He would have been half way on to the boat.”

Ross says the sea creature “looked liked a giant sculpin with big eyes, bigger than the rest of its body."

"It was full of barnacles, coral and had these rows of teeth – tusk looking things in his mouth. It didn’t have a whales tail, sort of like a cod tail.”

Their getaway

If it wasn’t for his father’s quick thinking to start the engine and wait until it got just close enough that it couldn’t turn, Ross shudders to think what would have happened.

“If people would have found wreckage of our boat, they would have thought we were run over by a steamer. Who would have thought we got ate by a sea monster?”

At the time of the encounter Ross says the boat was weighted to an anchor.

“We just shot up over the anchor and we could hear it hit the stern of the boat. It kept coming and kept raising out of water probably 10 to 15 feet out of water with its mouth wide open. If it had kept coming the top of his mouth would have been over my head.”

Dumfounded, the two fishermen sat there for about an hour and never spoke.

But "by and by," he says, they heard it again.

The swishing noise.

"We didn’t press our luck. We hauled anchor and took off. We seen this boat on our radar, so we steamed down to the boat. It was Eisner Penney, the guy that seen it Monday. I said to him, 'Eisner you want to get out of here if you see what we just seen,' and I remember him saying just as plain, ‘You don’t have to tell me what you seen because I seen it Monday.'"

That was enough fishing for everyone.

Penney threw everything in the middle of his platform and they all headed in.

"If there's a devil, that was it"

When fellow fisherman Edgar Nickerson initially heard about the sea creature encounter, he had laughed, according to an interview and story in the July 14, 1976, Yarmouth Vanguard newspaper.

“I thought it was funny. As a matter of fact, on Friday I bragged on my radio that I had Pollock Shoal all by myself,” he had said in the interview.

Only they weren't alone.

Nickerson and his 15-year-old son Robert were pulling gear when the sea creature appeared.

“It kept coming up. I thought it was a whale and I kidded to my son that it was coming after him," he had told Vanguard journalists Fred Hatfield and Alain Meuse 45 years ago.

"I turned on my sounder. That usually scare whales away. But not this thing. It kept coming and coming."

"It was a horrible looking thing I tell you. If there’s a devil, that was it.”

After the encounters, nobody went fishing for a few weeks, Ross says.

“We didn’t go back there that year. When three different boats on three different days seen this creature in the same area, something was there.”

Ross remembers coming home the day after seeing the sea creature and going to visit his neighbours Weldon Cox and Seaton Nickerson, who were retired fishermen that had made a living on the water all their lives.

“They always waved for me to come over, so I went over and told my story. They looked at me and said back in 1930s . . . they told me the names of two fishermen who had an encounter with a creature off here, much the same as what we seen," says Ross, who can’t remember the names he was given.

Ross notes all of the sightings were two days apart and all of the fishermen who saw the sea creature were on fishing boats that were green.

Over the years, he's collected clippings and mementos about the encounter, and about other sea creature encounters that people have sent to him.

Ongoing interest

Back in the 1970s or 1980s, Ross gave a talk to the students at the Barrington Municipal High School about the encounter. He still has all the thank you letters and pictures drawn by the students of what they thought it looked like. Whatever they had seen was dubbed the South Side Sea Monster.

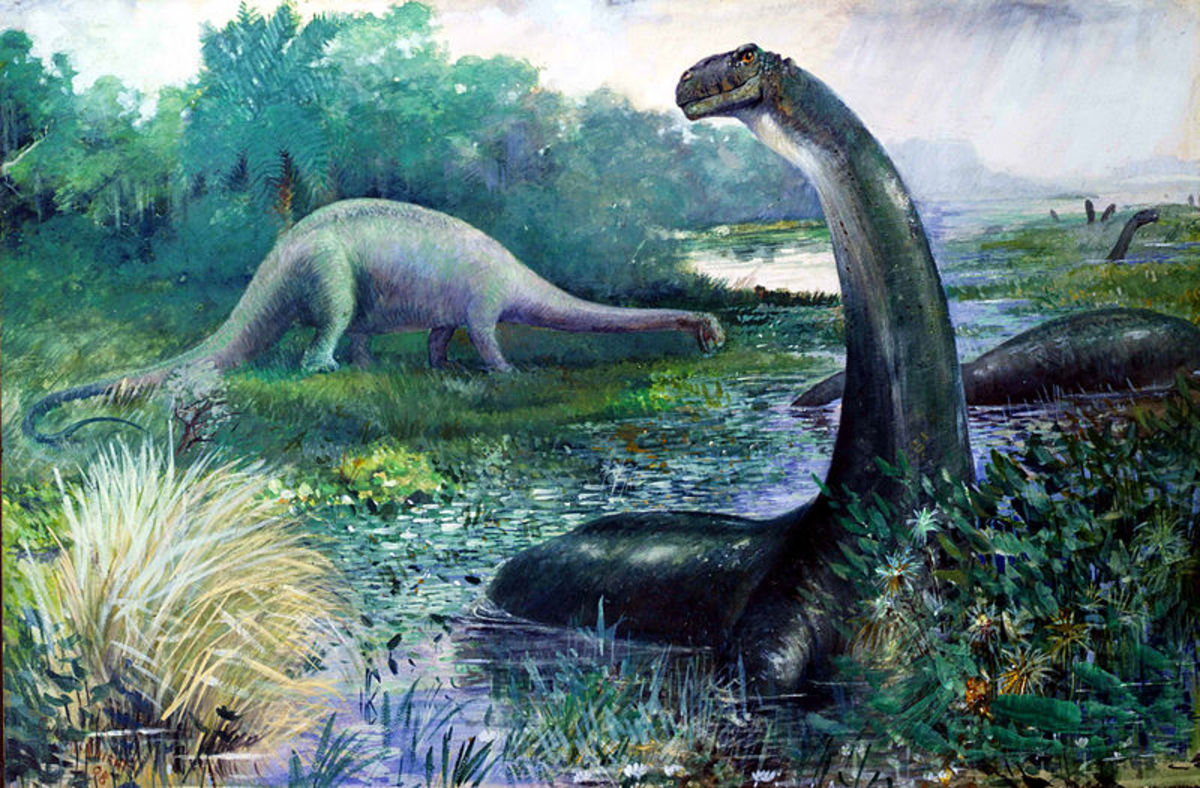

“When my father was living, people used to call him all the time,” says Ross. “We had a guy come from Florida one time; he was telling us about how many different things they discover every year. It could be ants, could be anything. Wartime they used to dump stuff in really deep water … it could have been something got into that,” he says, and was deformed.

Or something that was in an underwater cave had gotten out, or some sort of prehistoric thing, speculates Ross.

“Who knows what’s out there? It’s a big ocean,” he says.

Ross says he's usually contacted several times a year from someone wanting to know about the encounter.

Last fall Ross he was contacted by award winning author Max Hawthorne of New York who wanted to include Ross’s experience in a book he was writing. The book, 'Monsters and Marine Mysteries,' was just released several months ago. “I’m one of the chapters," says Ross.

Ross has only publicly spoke about his encounter a few times over the years. One of his presentations made in 2017 – South Side Sea Monster Story – is available on YouTube.

What's in the ocean? Sea serpent stories

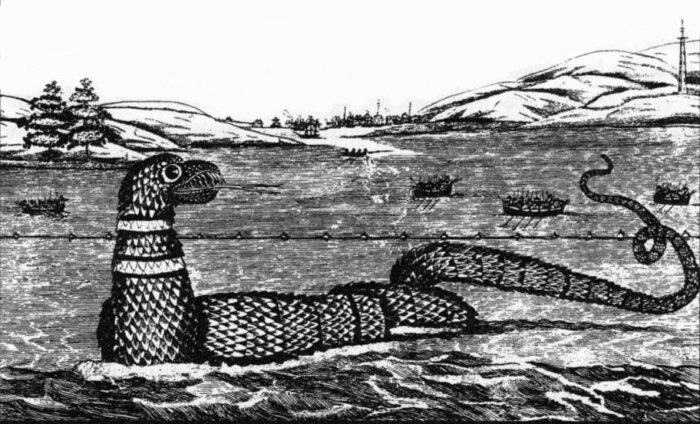

Throughout the years there have been numerous documented sightings of sea serpents, mermaids, mermen, giant lizards and squid, monstrous fish, and a great sea monster in waters off Nova Scotia’s coastline.

The Serpent Chronologies, Sea Serpents and other Marine Creatures from Nova Scotia’s History, published by the Nova Scotia Museum in 2015, “is an annotated, systematic, account of reports of sightings of large serpents and other mysterious creatures recorded in Nova Scotia waters.” It includes Mi’kmaw petroglyphs, elements of captured oral history and documents excerpted from both the popular press as well as the scientific literature over the centuries, reads the abstract.

“Where appropriate, these are discussed in terms of the culture of the times, as well our current understanding of natural history. Illustrations have been created where there was sufficient information recorded, and based on these and the descriptions provided, these drawings reflect the nature of the creatures described in a modern context." it reads. "It becomes evident that the chronology of such reports is a reflection, to a great part, of the state and development of both popular and scientific cultures of Nova Scotia throughout these times.”

The book, available to download as a PDF, chronicles documented sightings from the 1600s up to 2003, when there was an encounter with a sea serpent in Alder Point, Cape Breton.

Written by Andrew J Hebda, the author concludes by saying, “As was pointed out in the beginning: Some of these are true accounts of events while others may be exercises in creativity in writing. In some cases, it is not obvious which is which.

"We should keep in mind what the late Dr. Fred Aldrich was reported to have said when commenting on marine marvels in the North-West Atlantic Ocean: 'We know more about the backside of the moon than the bottom of the sea.'”

The first photo allegedly showing the existence of the Loch Ness monster was taken in 1934 by R. K. Wilson, a respected surgeon, and published in the Daily Mail.

The first photo allegedly showing the existence of the Loch Ness monster was taken in 1934 by R. K. Wilson, a respected surgeon, and published in the Daily Mail.