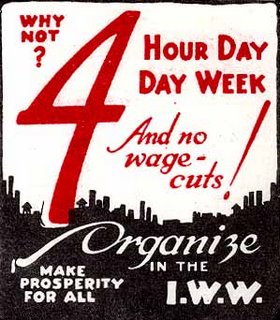

The revolutionary struggle of workers has always been a struggle to take back our time, as Marx noted in the Grundrisse and Lafargue wrote in his famous pamphlet The Right To Be Lazy, updated by Bob Black as The Abolition of Work

With the end of the craft/trade/artisan culture and the advent of industrial capitalism, we wage slaves have struggled to gain more time for ourselves, since it is only our time we have to sell. Our skills are easily replaceable. This is what is key to a Marxist understanding of the conditions of workers under capitalism.

The struggle to abolish capitalism is the struggle to abolish work/wage-slavery as we know it.

So take your damn vacation time and quit working for the boss.

Canadian employees put having more vacation days on the top of their most-wanted list, but according to a recent survey, fewer individuals are actually taking their days off. And that may be putting Canadian workers on the road to burnout.

In a recent Ipsos Reid and Expedia.ca survey, one in five Canadians said they would take a lower salary for more vacation time. Yet, despite the desire for more days off, the survey reveals that Canadians are falling behind on the number of vacation days they are actually taking. Some 24% of employed Canadians don't use all of their vacation days, and one in ten say they don't usually take any days.

In offices, shops and factories across the country, workers are nursing a seasonal martyr complex. School is out, the legislatures are deserted, the temperatures are high and the beaches are jammed. It seems as if everybody is on vacation — except them.

If you're one of those people, you're actually less alone than you feel.One-quarter of Canadian workers don't take their allotted vacation time. Ten per cent don't take any holidays at all. Even those who do get away often feel compelled to check their email and phone messages.According to a poll conducted by Ipsos Reid this spring, Canadians take an average of 19 vacation days a year. That is down from 21 days in last year's survey. It is below the French average of 39 days, German average of 27 days and British average of 23 days (but above the American average of 14 days.)Worker protection is in question as Canada's clothing and textile industries try to compete with cheap foreign labour.

Chances are that no one will ever know precisely what led to the death of Yvan Vachon on a spring afternoon nearly two years ago when he was found entwined in a 600-metre fabric roll in the midst of it being spun by a rolling machine. The 49-year old, a textile plant operator with some 20 years experience and the president of the local union, was replacing a co-worker on vacation when the dreadful accident took place. Vachon, who had just completed two weeks of training to grasp the inner workings of that particular machine, was walking through a narrow 35-cm wide passageway to go from one end of the machine to the

other when his hand apparently got caught in-between two rollers, according to an investigation by the Quebec Workers’ Compensation Board. He died later that day in hospital.

Vacation angst prevalent among workers

U.S. workers are taking fewer vacation days and enjoying the ones they take less amid skyrocketing anxiety over the retreats, a New York nonprofit said.The Families and Work Institute, which researches the habits of American workers, said vacation anxiety can come from a fear of unemployment, The New York Times reported Thursday.

As school starts, summer shrinks for all of us

According to information the U.S. Census Bureau released last year, 7.3 million workers in the U.S. have more than one job, and 28 percent of workers 16 or older work more than 40 hours a week. Another 8 percent work 60 or more hours.

According to a report released this year by Steelcase, an office furniture manufacturer, 43 percent of nearly 700 U.S. office workers surveyed spent at least some time working while on vacation. That number has almost doubled in the last 10 years.

Machinery and surplus labour. Recapitulation of the doctrine of surplus value generally

If we look at a single worker's day, then the decrease of necessary labour relative to surplus labour expresses itself in the appropriation of a larger part of the working day by capital. The living labour employed here remains the same. Suppose that an increase of the force of production, e.g. employment of machinery, made 3 workers superfluous out of 6, each of whom worked 6 days a week. If these 6 workers themselves possessed the machinery, then each of them would thereafter work only half a day. Now, instead, 3 continue to work a whole day every day of the week. If capital were to continue to employ the 6, then each of them would work only half a day, but perform no surplus labour. Suppose that necessary labour amounted to 10 hours previously, the surplus labour to 2 hours per day, then the total surplus labour of the 6 workers was 2 x 6 daily, equal to a whole day, and was equal to 6 days a week = 72 hours. Each one worked one day a week for nothing. Or it would be the same as if the sixth worker had worked the whole week long for nothing. The 5 workers represent necessary labour, and if they could be reduced to 4, and if the one worker worked for nothing as before—then the relative surplus value would have grown. Its relation previously was = 1:6, and would now be 1 5. The previous law, of an increase in the number of hours of surplus labour, thus now obtains the form of a reduction in the number of necessary workers. If it were possible for this same capital to employ the 6 workers at this new rate, then the surplus value would have increased not only relatively, but absolutely as well. Surplus labour time would amount to 14 2/5 hours. 2 2/5 hours [each] performed by 6 workers is of course more than 2 2/5 performed by 5.

If we look at absolute surplus value, it appears determined by the absolute lengthening of the working day above and beyond necessary labour time. Necessary labour time works for mere use value, for subsistence. Surplus labour time is work for exchange value, for wealth. It is the first moment of industrial labour. The natural limit is posited—presupposing that the conditions of labour are on hand, raw material and instrument of labour, or one of them, depending on whether the work is merely extractive or formative, whether it merely isolates the use value from nature or whether it shapes it—the natural limit is posited by the number of simultaneous work days or of living labour capacities, i.e. by the labouring population. At this stage the difference between the production of capital and earlier stages of production is still merely formal. With kidnapping, slavery, the slave trade and forced labour, the increase of these labouring machines, machines producing surplus product, is posited directly by force; with capital, it is mediated through exchange.

The tendency of capital is, of course, to link up absolute with relative surplus value; hence greatest stretching of the working day with greatest number of simultaneous working days, together with reduction of necessary labour time to the minimum, on one side, and of the number of necessary workers to the minimum, on the other. This contradictory requirement, whose development will show itself in different forms as overproduction, over-population etc., asserts itself in the form of a process in which the contradictory aspects follow closely upon each other in time. A necessary consequence of them is the greatest possible diversification of the use value of labour—or of the branches of production—so that the production of capital constantly and necessarily creates, on one side, the development of the intensity of the productive power of labour, on the other side, the unlimited diversity of the branches of labour, i.e. thus the most universal wealth, in form and content, of production, bringing all sides of nature under its domination.Work Sucks

IWW

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

work, vacation, Canda, US, Marx, Lafargue, Black, Grundrisse, four-hour-day

No comments:

Post a Comment