ESG insiders demand course correction to fix industry woes

,

Bloomberg News

Jun 7, 2022

With ESG being increasingly maligned these days from both the inside and the outside, some of the industry’s early devotees say it’s time for a course correction.

Jerome Dodson, the retired founder of one of the world’s largest ESG-focused investing firms, said a dedicated watchdog is needed to help police marketing claims. Marcela Pinilla, who’s worked in the business for 15 years, said environmental, social and governance issues need to be considered separately as opposed to lumped together under one acronym. And Matthew Kiernan, a pioneer of ESG corporate ratings, said both the industry and regulators need to double their efforts to stamp out exaggerated claims and root out bad actors.

The current maelstrom should be seen as “manna from heaven,’’ said Kiernan, co-founder of Invest Green, a Toronto-based firm that educates investors on sustainable investing. “It should ideally catalyze a big shakeout, an incursion on greenwashing and result in a smaller, leaner industry with much better clarity and quality.''

The list of insiders discomfited by the growth of the industry — valued at about US$40 trillion by analysts at Bloomberg Intelligence — has jumped exponentially in the past year. They bemoan newer entrants that have jumped on the bandwagon to market investments that have little real-world impacts. They say widely used ESG ratings are riddled with errors and need to be standardized, and they want asset-management firms to to face tougher scrutiny.

After doing little during the early years of the ESG bonanza, regulators are trying to catch up. Just last month, the US Securities and Exchange Commission proposed a slate of new restrictions aimed at ensuring ESG funds accurately describe their investments. Some also would need to disclose the aggregated greenhouse gas emissions of companies they’re invested in, according to the SEC.

Dodson, who used to run Parnassus Investments and has described the market boom as “disconcerting,’’ called for the creation of a group modeled on Wall Street watchdog, Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. It should be a nonprofit organization backed by the government that charges fees, conducts audits and exams, and has enforcement powers, he said.

The end result would be more firms getting kicked out of the business for failing to adhere to the highest investing and marketing standards, said Dodson, who retired last year from Parnassus, which he founded in 1984. The firm now manages US$47 billion from San Francisco.

When the investment strategy was conceived in the mid-2000s, its intention was to help investors measure risks and opportunities from environmental, social and corporate governance-related issues. It’s now morphed into a myriad of investment strategies ranging from mutual funds to complex derivatives designed by Wall Street banks.

For Pinilla, director of sustainable investing at Boston-based Zevin Asset Management, the criticisms are welcome because they shine a spotlight on widening concerns about industry practices, especially among newer entrants. This rethink will help separate “the wheat from the chaff,’’ she said. “We need to be examined. It will help people get more precise about what exactly they’re doing.’’

Pinilla said ESG needs to be “decentralized” so those making claims specifically spell out their analysis of risks associated with “the E, the S and the G.” For example, investors would analyze workplace diversity as a separate topic from greenhouse gas emissions and corporate governance rather than lumping their analysis together, she said.

“While they intersect, they need to be understood individually, not neatly bundled together,’’ she said.

It’s an approach that would make it harder for fund managers to claim that Tesla Inc., for example, lives up to the ESG label. While the electric-vehicle maker meets the standards of an environmentally friendly stock, its track record on social and governance issues raises a lot of awkward questions.

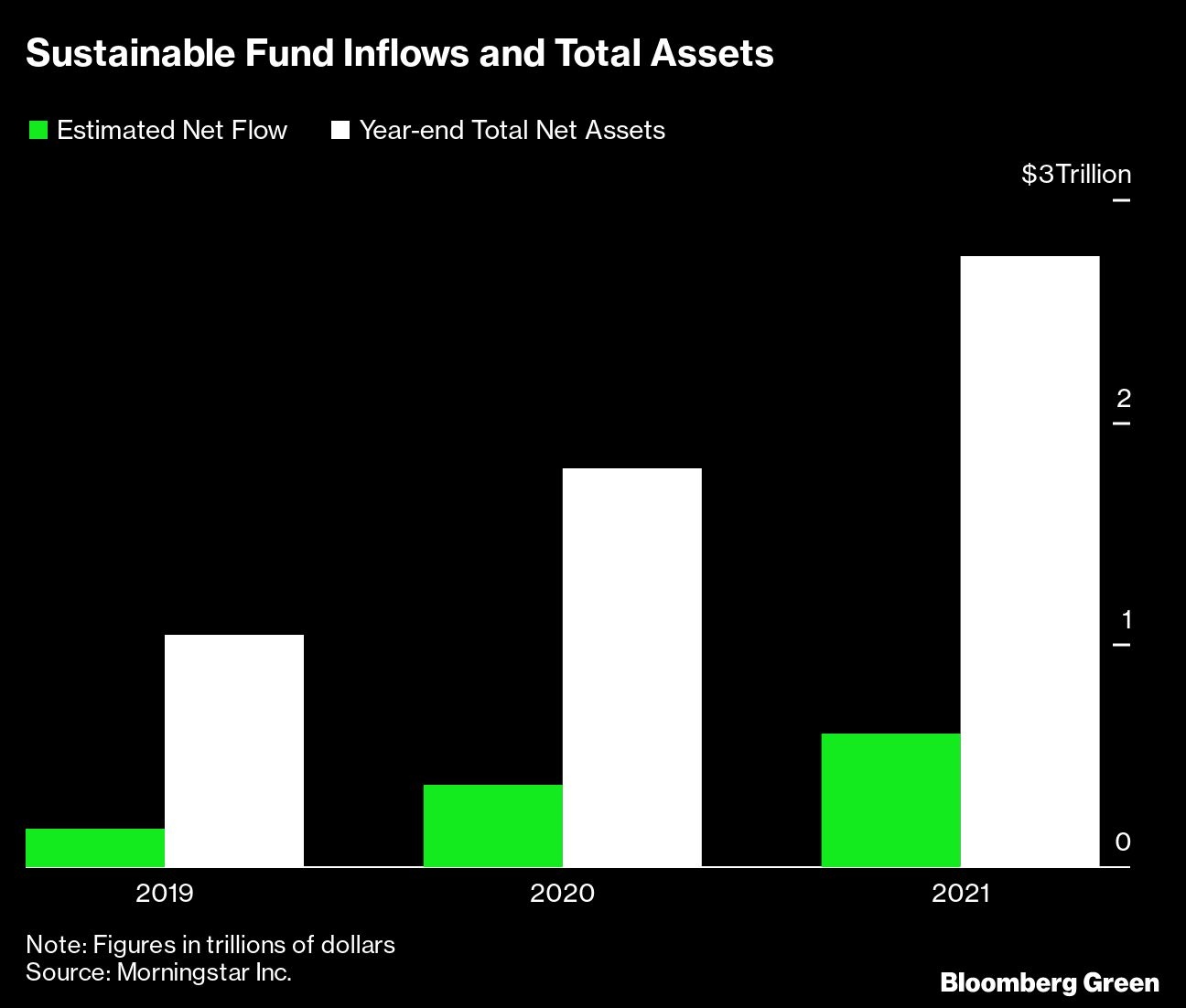

Early signs have emerged that investors are souring on the process. They pulled a record net US$2 billion from US equity exchange-traded funds in May, ending three years of inflows, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. The redemptions are early signs of investors’ concerns about ESG as global financial markets are rattled by inflation and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Kiernan, whose scores became the foundation for those sold today by MSCI Inc., the world’s biggest provider of ESG ratings, said the industry needs to double its efforts to fix the ratings system because they’re inconsistent and too many money managers use them to decide what stocks to buy.

Additionally, industry groups need to raise their standards to winnow out fund managers who aren’t following through on their commitments to the strategy, while institutional investors need to be more discerning about which managers they give their money to so that money only flows to those that are doing bona fide sustainable investing, he said.

If these three steps are taken, the amount of money investing in so-called sustainable funds would drop in half from the US$2.7 trillion now estimated by Morningstar Inc., Kiernan said. While there will be “a rather awkward transition,’’ it will ultimately result in genuine ESG funds “standing out and attracting more capital,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment