By Joshua Hawkins

Published Feb 19th, 2023

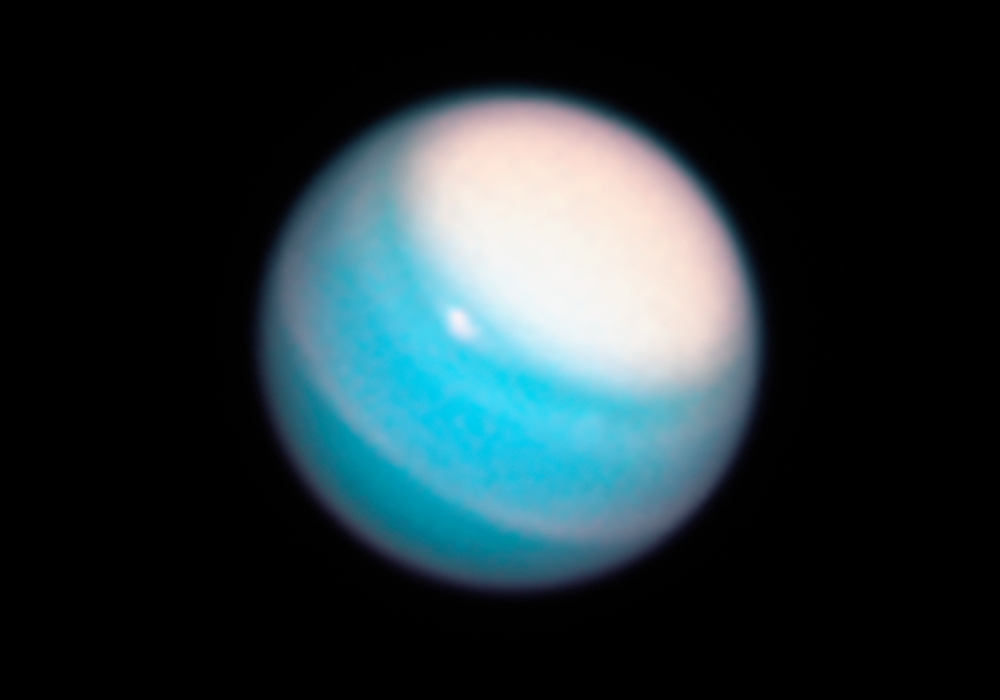

Image: NASA, ESA, A. Simon, and M.H. Wong and A. Hsu

It has been over 30 years since humanity last visited Uranus in any capacity. In fact, the last time that humanity paid a brief visit to the ice giant was January 24, 1986, when NASA’s Voyager 2 probe flew past the planet on its way to Neptune. It was the first time we got a proper view of the planet and its moons. Now, scientists are once again calling for a dedicated mission to Uranus to help solve its mysteries.

Like Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus and its twin, Neptune, are packed with gasses like hydrogen and helium. However, Neptune and Uranus have more elements that are heavier relative to hydrogen than the other two giants of our solar system. As such, we’ve come to refer to them as ice giants. And the images that Voyager 2 gave us have only left astronomers wanting to know more about Uranus.

And yet, over 30 years later, here we are with no better looks at the planet than we’ve ever had before. The need for a dedicated mission to Uranus isn’t news. In fact, it’s something I’ve covered before here on the site. Back in April of 2022, science advisors in the U.S. were pushing hard for a mission to probe Uranus. A mission that would undoubtedly teach us more about this icy giant.

The lack of a mission to Uranus has been identified as a problem before in NASA’s decadal review. Learning more about the ice giants that call our solar system home is a top priority for the coming decade. This is why it wouldn’t be surprising to see NASA or others announcing dedicated missions to Uranus. It just seems like it’s going to take some time.

An essay, published in mid-February by Kathleen Mandt points out that both the Mars Sample Return and Europa Clipper missions were ranked above a Uranus Orbiter and Probe in the 2003-2013 decadal survey, as well as the 2013-2023 decadal survey. Both those missions are well into their development, which means a dedicated mission to Uranus could be next on the books.

But it isn’t just astronomers’ curiosity that has them wanting to send a probe to study Uranus. It’s the fact that understanding how the ice giants formed and migrated could have “broad implications for explaining the distribution of small bodies in our solar system,” as Mandt explains in her essay.

Sending a dedicated mission to Uranus could help us in a lot of ways, including understanding how life-supporting elements were delivered to the inner solar system, and even beyond it. And it’s this increased possibility of understanding that has made astronomers care so much about a UOP.

Planetary scientist lays out arguments for sending a dedicated probe to Uranus (Update)

Kathleen Mandt, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory has published a Perspectives piece in the journal Science arguing that NASA should send a dedicated probe to the planet Uranus. She notes that a window is opening in 2032 for the launch of such a probe.

Planetary scientists have spent far more time studying Mars than they have other planets, partly due to its close proximity and partly due to the fact that Mars has a surface upon which craft can land. Planets that have thick atmospheres, on the other hand, are more difficult to study, especially if they provide no place to land.

Still, Mandt argues, such research is important. And initiating the development of a probe to study Uranus, she adds, would be a good start. She further notes that now would be a good time to begin such plans because the next good window for launching a Uranus probe would be in 2032, when Jupiter's alignment with Earth will allow a slingshot maneuver toward Uranus. She even suggests a name for the probe: the Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP).

Uranus is considered to be the odd duck of the solar system because of its 90-degree tilt relative to its orbit path—its tilt gives it the appearance of rolling along a plane. The tilt also gives the planet extreme seasonal variation as it circles the sun once every 84 years. And it makes observations from Earth cloudy and hazy, which is not very conducive to research efforts. Only one craft has ever ventured to Uranus—Voyager II, back in 1986—and it only flew by on its way to Neptune.

Uranus is considered an ice giant because of the two heavy elements that make up the bulk of its atmosphere: helium and hydrogen. It also has 27 moons that circle the planet, following its odd tilt. Uranus also has what Mandt describes as "strange rings."

She also notes that not much else is known about the planet, which is why NASA needs to place a probe into permanent orbit around it. The probe would reveal the true nature of the planet's atmosphere, determine if its core is made of rock or ice, and perhaps explain how it came to have such a strange tilt. It also might help in efforts aimed at learning how ice giants form.

More information: Kathleen E. Mandt, The first dedicated ice giants mission, Science (2023). DOI: 10.1126/science.ade8446

Journal information: Science

© 2023 Science X Network

No comments:

Post a Comment