The Conversation

April 27, 2024

Man on a computer (Credit: Shutterstock)

Websites sometimes hide how widely they share our personal information, and can go to great lengths to pull the wool over our eyes. This deception is intended to prevent full disclosure to consumers, thus preventing informed choice and affecting privacy rights.

Governments are responding to consumer concerns about privacy with legislation. These include the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). The impact of this legislation is visible as websites request permission to track online user activity.

However, many users remain unaware of the impact of these choices, or how the extent of sharing is deceptively hidden.

Websites and privacy

As Canadian policymakers grapple with updates to online privacy regulations, our research looks at when and why companies actively hide — and how widely they share — our personal data. We found that the obfuscation, or disguise, of information sharing is a strategy commonly used by websites to mislead users and raise the cost of monitoring.

Our research team has been studying website privacy issues for a number of years, specifically with respect to the sharing of consumer data with third parties as a way to monetize web traffic.

Our research has established that websites with privacy-sensitive content, such as medical and banking websites, are naturally constrained by the market in terms of their third-party sharing. These websites are also more privacy-sensitive, and so are less likely to obscure the extent of information-sharing.

We also examined the privacy abuses that occurred as people’s use of online services increased in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted research that allowed us to predict website trustworthiness by observing how they employed third parties. We discussed how opt-in privacy legislation can increase third-party sharing.

Gathering and sharing of data

We examined third-party data collection by websites, highlighting the extensive tracking mechanisms deployed by platforms and advertisers to capture consumer information. This pervasive surveillance raises significant concerns about privacy infringement and the commodification of personal data.

Within the first three seconds of opening a web page, over 80 third parties on average have accessed your information. Some of these third parties provide services to improve a website’s functionality and performance.

Other third parties are engaged in advertising and targeted advertising, which includes scooping up and selling your most personal information. Some third parties are extremely predatory in their privacy abuses.

Our research reveals circumstances where websites actively hide how widely our data is shared. As content sensitivity increases — for example, websites dealing with sensitive personal medical information — websites reduce the level of deception compared to websites with less sensitive content.

We also found that websites that are more popular are more likely to hide their data-sharing practices than websites with smaller audiences.

Websites modify how widely they share user information and hide how much they share because it can sometimes help increase profits by taking advantage of unknowing consumers. This means that visitors are unable to make fully informed decisions regarding their data privacy.

Similar to ambiguous website privacy policies, requesting consent to collect and share information does not necessarily resolve the information asymmetry between websites and users. A common strategy is to overwhelm users with an overly extensive list of third parties that do not necessarily reflect their particular interaction.

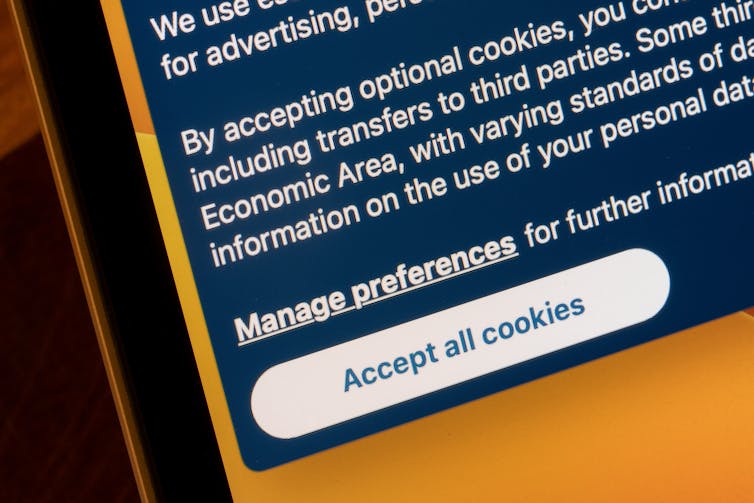

Asking for consent to gather information is a gesture that can hide a website’s actions. (Shutterstock)

Pervasive surveillance

Websites use a variety of techniques to keep users from understanding the true level of information sharing and its privacy implications. One deception is the use of dark patterns, defined as “user interface design choices that benefit an online service by coercing, steering or deceiving users into making unintended and potentially harmful decisions.” These dark patterns trick users into giving away their privacy.

Another deception technique relates to the lack of transparency surrounding third-party sharing. Who websites share information with depends upon a myriad of variables — the consumer never knows how or why their information is shared. Third parties can differ depending on where a user is located: third-party sharing across the largest 100,000 websites is on average higher for customers clicking from California compared to New York, for example.

Obfuscated customization occurs when the website actively tries to hide their abusive third party sharing. For example, consumers can use a Do Not Track (DNT) request: however, websites can make it difficult for users to understand the website’s response to the request, and it is very difficult to figure out what happens after the request is made.

Sometimes, websites actually track users more in response to a DNT request. In an unpublished experiment that we performed, 40 per cent of the top 100 largest news websites in the world shared your data with more third parties if you made a DNT request. Even if a website engages fewer third parties, the changes in response to a DNT request may still be abusive because they may now share data with more intrusive third parties.

Consumer responses

Consumers may use various tools to protect themselves, including virtual private networks (VPNs), behavioural obfuscation and lying about their personal information.

Simply disclosing the presence of third parties and requesting user consent is insufficient because the consumer, for all practical purposes, is unaware of the extent of third-party sharing and tracking. Because of this information asymmetry, it is impossible to know when or to what extent personal information has been shared.

The EU’s GDPR and California’s CCPA contain opt-in and opt-out regulations, such as those currently under consideration in Canada. But one thing is clear: these regulations are not enough to stop websites from manipulating and profiting from user data.

Raymond A. Patterson, Professor, Area Chair, Business Technology Management, Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary; Ashkan Eshghi, Houlden Fellow, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick; Hooman Hidaji, Assistant Professor of Business Technology Management, University of Calgary, and Ram Gopal, Professor of Information Systems Management, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment