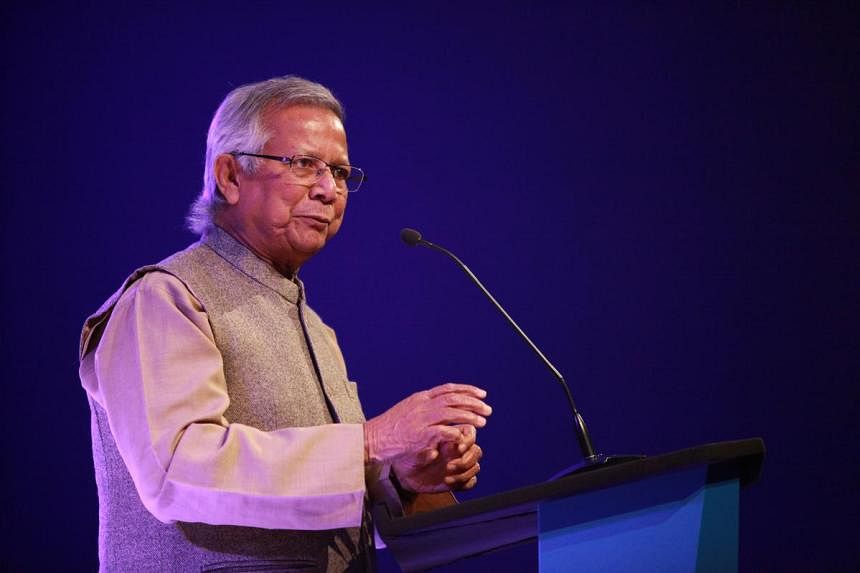

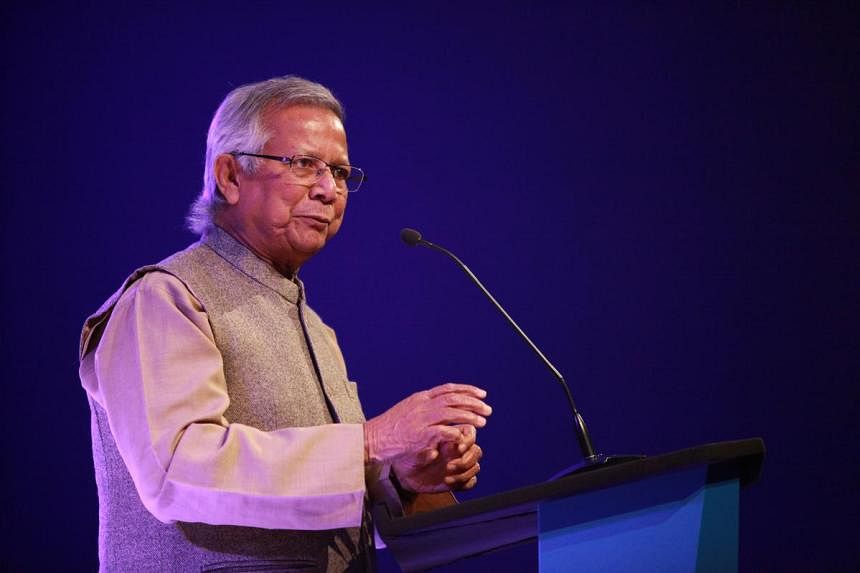

Bangladesh Nobel laureate Yunus agrees to lead interim govt: spokesperson

Bangladesh's student protesters have lobbied for Yunus to fill the vacuum left by ousted PM Sheikh Hasina.

Reuters Archive

Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus has launched his microcredit system from one of the world's most poverty-stricken countries. / Photo: Reuters Archive

Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus has agreed to lead the interim Bangladesh government after the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina following a weeks-long deadly protest, his spokesperson announced on Tuesday.

Yunus will fill the vacuum left by Hasina, who fled the country after violence surged in the streets on Monday.

Yunus had been in Paris, France, for a minor medical procedure, his spokesperson said. He is to return to Bangladesh 'immediately' once his doctors approve.

Bangladesh was rocked by demonstrations that began as a protest against government quotas for jobs, but escalated out of control as protesters expressed their dissatisfaction with the 15-year-governance of Sheikh Hasina and demanded her resignation.

On August 5, 2024, Hasina tendered her resignation and fled Bangladesh for India. Her future plans are unknown although there are media reports that she will travel on to the UK.

The Bangladeshi army has invited all citizens to peaceful de-escalation, saying an interim government would be set up until elections could be held in the country.

Student leaders, speaking on behalf of many protesters, had made it clear that they preferred Muhammad Yunus to guide Bangladesh as the interim government seeks to establish order and unity.

Bangladesh's student protesters have lobbied for Yunus to fill the vacuum left by ousted PM Sheikh Hasina.

Reuters Archive

Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus has launched his microcredit system from one of the world's most poverty-stricken countries. / Photo: Reuters Archive

Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus has agreed to lead the interim Bangladesh government after the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina following a weeks-long deadly protest, his spokesperson announced on Tuesday.

Yunus will fill the vacuum left by Hasina, who fled the country after violence surged in the streets on Monday.

Yunus had been in Paris, France, for a minor medical procedure, his spokesperson said. He is to return to Bangladesh 'immediately' once his doctors approve.

Bangladesh was rocked by demonstrations that began as a protest against government quotas for jobs, but escalated out of control as protesters expressed their dissatisfaction with the 15-year-governance of Sheikh Hasina and demanded her resignation.

On August 5, 2024, Hasina tendered her resignation and fled Bangladesh for India. Her future plans are unknown although there are media reports that she will travel on to the UK.

The Bangladeshi army has invited all citizens to peaceful de-escalation, saying an interim government would be set up until elections could be held in the country.

Student leaders, speaking on behalf of many protesters, had made it clear that they preferred Muhammad Yunus to guide Bangladesh as the interim government seeks to establish order and unity.

‘Today feels like a second Liberation Day,’ Bangladesh Nobel laureate Yunus tells FRANCE 24

Bangladesh student protest leaders said Tuesday they wanted Nobel laureate and microfinance pioneer Muhammad Yunus, 84, to lead an interim government. Yunus spoke to FRANCE 24 about the popular uprising that precipitated Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's fall and his hopes for a more democratic future for the country.

Issued on: 06/08/2024 -

By: FRANCE 24

Bangladesh student protest leaders said Tuesday they wanted Nobel laureate and microfinance pioneer Muhammad Yunus, 84, to lead an interim government. Yunus spoke to FRANCE 24 about the popular uprising that precipitated Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's fall and his hopes for a more democratic future for the country.

Issued on: 06/08/2024 -

13:04© FRANCE 24

By: FRANCE 24

Video by: Mark OWEN

A key organiser of Bangladesh’s student protests Tuesday called for Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus to be named as the head of a new interim government, a day after longtime Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina resigned and fled the country after weeks of deadly unrest.

Yunus, who called Hasina’s resignation the country's “second Liberation Day”, faced a number of corruption accusations and was put on trial during the former prime minister’s rule. He received the Nobel in 2006 after he pioneered microlending, and he said the corruption charges against him were motivated by vengeance.

A key organiser of Bangladesh’s student protests Tuesday called for Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus to be named as the head of a new interim government, a day after longtime Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina resigned and fled the country after weeks of deadly unrest.

Yunus, who called Hasina’s resignation the country's “second Liberation Day”, faced a number of corruption accusations and was put on trial during the former prime minister’s rule. He received the Nobel in 2006 after he pioneered microlending, and he said the corruption charges against him were motivated by vengeance.

Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus was arch-foe of ousted Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina

Exiled Bangladeshi author Taslima Nasreen takes a dig at Sheikh Hasina's ouster with 'same Islamists' remark

Muhammad Yunus won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for work done by Grameen Bank, which he founded.

Updated

Aug 06, 2024

DHAKA – Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, the pioneer of the global microcredit movement who could shepherd Bangladesh’s new interim government, was an arch foe of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has resigned and fled the country.

Known as the “banker to the poor”, Yunus and the Grameen Bank he founded won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for helping to lift millions from poverty by providing tiny loans of sums less than US$100 (S$133) to the rural poor who were too impoverished to gain attention from traditional banks.

Their lending model has since inspired similar projects around the world, including developed countries like the United States, where Yunus started a separate non-profit Grameen America.

As his success grew, Yunus, now 84, flirted briefly with a political career, attempting to form his own party in 2007. But his ambitions were widely viewed as having sparked the ire of Ms Hasina, who accused him of “sucking blood from the poor”.

Critics in Bangladesh and other countries, including neighbouring India, have also said microlenders charge excessive rates and make money out of the poor. But Yunus said the rates were far lower than local interest rates in developing countries or the 300 per cent or more that loan sharks sometimes demand.

In 2011, Ms Hasina’s government removed him as head of Grameen Bank, saying that at 73, he had stayed on past the legal retirement age of 60. Thousands of Bangladeshis formed a human chain to protest against his sacking.

In January 2024, he was sentenced to six months in prison for violations of labour law.

He and 13 others were also indicted by a Bangladesh court in June on charges of embezzlement of 252.2 million taka (S$2.8 million) from the workers’ welfare fund of a telecommunications company he founded.

Although he was not jailed in either case, Yunus faces more than 100 other cases on graft and other charges. He denies any involvement and said during an interview with Reuters that the accusations were “very flimsy, made-up stories”.

“Bangladesh doesn’t have any politics left,” he said in June, criticising Ms Hasina. “There’s only one party which is active and occupies everything, does everything, gets to the elections in their way.”

He told Indian broadcaster Times Now that Aug 5 marked the “second liberation day” for Bangladesh after its 1971 war of independence from Pakistan following the exit of Ms Hasina.

Yunus is currently in Paris undergoing a minor medical procedure, his spokesperson said, adding that he has agreed to the request of students who led the campaign against Ms Hasina to be the chief adviser of the interim government.

Yunus was an economist teaching at the University of Chittagong when famine struck Bangladesh in 1974, killing hundreds of thousands of people and leaving him searching for better ways to help his country’s vast rural population.

That opportunity arrived when he came across a woman in a village near the university who had borrowed from a moneylender. The amount was less than a dollar but, in return, the moneylender gained the exclusive right to buy everything the woman produced at a price to be determined by the moneylender.

“This, to me, was a way of recruiting slave labour,” Yunus said in his Nobel acceptance speech.

He found 42 people who borrowed a combined US$27 from the moneylender and lent them the funds himself – the success of that endeavour spurring him on to do more and think of credit as a basic human right.

“When I gave the loans, I was astounded by the results I got. The poor paid the loans on time every time.”

Aug 06, 2024

DHAKA – Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, the pioneer of the global microcredit movement who could shepherd Bangladesh’s new interim government, was an arch foe of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has resigned and fled the country.

Known as the “banker to the poor”, Yunus and the Grameen Bank he founded won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for helping to lift millions from poverty by providing tiny loans of sums less than US$100 (S$133) to the rural poor who were too impoverished to gain attention from traditional banks.

Their lending model has since inspired similar projects around the world, including developed countries like the United States, where Yunus started a separate non-profit Grameen America.

As his success grew, Yunus, now 84, flirted briefly with a political career, attempting to form his own party in 2007. But his ambitions were widely viewed as having sparked the ire of Ms Hasina, who accused him of “sucking blood from the poor”.

Critics in Bangladesh and other countries, including neighbouring India, have also said microlenders charge excessive rates and make money out of the poor. But Yunus said the rates were far lower than local interest rates in developing countries or the 300 per cent or more that loan sharks sometimes demand.

In 2011, Ms Hasina’s government removed him as head of Grameen Bank, saying that at 73, he had stayed on past the legal retirement age of 60. Thousands of Bangladeshis formed a human chain to protest against his sacking.

In January 2024, he was sentenced to six months in prison for violations of labour law.

He and 13 others were also indicted by a Bangladesh court in June on charges of embezzlement of 252.2 million taka (S$2.8 million) from the workers’ welfare fund of a telecommunications company he founded.

Although he was not jailed in either case, Yunus faces more than 100 other cases on graft and other charges. He denies any involvement and said during an interview with Reuters that the accusations were “very flimsy, made-up stories”.

“Bangladesh doesn’t have any politics left,” he said in June, criticising Ms Hasina. “There’s only one party which is active and occupies everything, does everything, gets to the elections in their way.”

He told Indian broadcaster Times Now that Aug 5 marked the “second liberation day” for Bangladesh after its 1971 war of independence from Pakistan following the exit of Ms Hasina.

Yunus is currently in Paris undergoing a minor medical procedure, his spokesperson said, adding that he has agreed to the request of students who led the campaign against Ms Hasina to be the chief adviser of the interim government.

Yunus was an economist teaching at the University of Chittagong when famine struck Bangladesh in 1974, killing hundreds of thousands of people and leaving him searching for better ways to help his country’s vast rural population.

That opportunity arrived when he came across a woman in a village near the university who had borrowed from a moneylender. The amount was less than a dollar but, in return, the moneylender gained the exclusive right to buy everything the woman produced at a price to be determined by the moneylender.

“This, to me, was a way of recruiting slave labour,” Yunus said in his Nobel acceptance speech.

He found 42 people who borrowed a combined US$27 from the moneylender and lent them the funds himself – the success of that endeavour spurring him on to do more and think of credit as a basic human right.

“When I gave the loans, I was astounded by the results I got. The poor paid the loans on time every time.”

REUTERS

Khaleda Zia, Bangladesh’s other female PM, to be freed after Hasina’s ouster

She lost to Ms Hasina in the 1996 elections but came back five years later. But her second term was marred by the rise of Islamist militants and allegations of corruption.

In 2004, a rally that Ms Hasina was addressing was hit by grenades. Ms Hasina survived, but over 20 people were killed and more than 500 were wounded.

Khaleda’s government and its Islamic allies were widely blamed and, years later, her eldest son was tried in absentia and sentenced to life for the attack. The BNP contended the charges were trumped up.

Although Khaleda later clamped down on Islamist radical groups, her second stint as prime minister ended in 2006, when an army-backed interim government took power amid political instability and street violence.

More On This Topic

Bangladesh’s Iron Lady Sheikh Hasina falls after 15 years in power

The interim government jailed both Khaleda and Ms Hasina on charges of corruption and abuse of power for about a year before they were both released ahead of a general election in 2008.

Although the BNP boycotted the 2008 election and Khaleda never regained power, the vitriolic feud with Ms Hasina that led to the two being dubbed “the battling Begums” continued to dominate Bangladeshi politics.

Tension between their two parties has often led to strikes, violence and deaths, impeding economic development for a poverty-stricken country of nearly 170 million that is low-lying and prone to devastating floods.

In 2018, Khaleda, her eldest son and aides were convicted of stealing some US$250,000 (S$331,000) in foreign donations received by an orphanage trust set up when she was last prime minister, charges that she said were part of a plot to keep her and her family out of politics.

She was jailed but released in March 2020 on humanitarian grounds as her health deteriorated. She has remained under house arrest since then.

Former prime minister Khaleda Zia has been under house arrest since March 2020.

Aug 06, 2024

DHAKA – Days ahead of her 79th birthday, Bangladesh’s first female prime minister Khaleda Zia is set to get a welcome gift: release from house arrest after anti-government protests ousted her bitter rival, Ms Sheikh Hasina, from power.

President Mohammed Shahabuddin ordered the immediate release of Zia, chief of the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), late on Aug 5 after discussing the formation of an interim government with politicians and the army.

Ms Hasina fled to India earlier in the day after resigni

Zia, born on Aug 15, 1945, has liver disease, diabetes and heart problems, according to her doctors. She has largely remained away from politics for many years.

Popularly known by her first name, Khaleda was described as shy and devoted to raising her two sons until her husband, military leader and then President of Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman was assassinated in an attempted army coup in 1981.

Plunging into politics, she became head of her husband’s conservative BNP three years later, vowing to deliver on his aim of “liberating Bangladesh from poverty and economic backwardness”

She joined hands with Ms Hasina, daughter of Bangladesh’s founding father and head of the Awami League party, to lead a popular uprising for democracy that toppled military ruler Hossain Mohammad Ershad from power in 1990.

But their cooperation did not last long and, the next year, Bangladesh held what was hailed as its first free election, with Khaleda winning a surprise victory over Ms Hasina, having gained the support of Islamic political allies.

In doing so, Khaleda became Bangladesh’s first female prime minister and only the second woman to lead a democratic government of a mainly Muslim nation after Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto.

Khaleda replaced the presidential system with a parliamentary form of government so that power rested with the prime minister, lifted restrictions on foreign investment and made primary education compulsory and free.

People celebrate after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled Dhaka following a groundswell of protests against her rule.

DHAKA – Days ahead of her 79th birthday, Bangladesh’s first female prime minister Khaleda Zia is set to get a welcome gift: release from house arrest after anti-government protests ousted her bitter rival, Ms Sheikh Hasina, from power.

President Mohammed Shahabuddin ordered the immediate release of Zia, chief of the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), late on Aug 5 after discussing the formation of an interim government with politicians and the army.

Ms Hasina fled to India earlier in the day after resigni

Zia, born on Aug 15, 1945, has liver disease, diabetes and heart problems, according to her doctors. She has largely remained away from politics for many years.

Popularly known by her first name, Khaleda was described as shy and devoted to raising her two sons until her husband, military leader and then President of Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman was assassinated in an attempted army coup in 1981.

Plunging into politics, she became head of her husband’s conservative BNP three years later, vowing to deliver on his aim of “liberating Bangladesh from poverty and economic backwardness”

She joined hands with Ms Hasina, daughter of Bangladesh’s founding father and head of the Awami League party, to lead a popular uprising for democracy that toppled military ruler Hossain Mohammad Ershad from power in 1990.

But their cooperation did not last long and, the next year, Bangladesh held what was hailed as its first free election, with Khaleda winning a surprise victory over Ms Hasina, having gained the support of Islamic political allies.

In doing so, Khaleda became Bangladesh’s first female prime minister and only the second woman to lead a democratic government of a mainly Muslim nation after Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto.

Khaleda replaced the presidential system with a parliamentary form of government so that power rested with the prime minister, lifted restrictions on foreign investment and made primary education compulsory and free.

People celebrate after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled Dhaka following a groundswell of protests against her rule.

She lost to Ms Hasina in the 1996 elections but came back five years later. But her second term was marred by the rise of Islamist militants and allegations of corruption.

In 2004, a rally that Ms Hasina was addressing was hit by grenades. Ms Hasina survived, but over 20 people were killed and more than 500 were wounded.

Khaleda’s government and its Islamic allies were widely blamed and, years later, her eldest son was tried in absentia and sentenced to life for the attack. The BNP contended the charges were trumped up.

Although Khaleda later clamped down on Islamist radical groups, her second stint as prime minister ended in 2006, when an army-backed interim government took power amid political instability and street violence.

Bangladesh’s Iron Lady Sheikh Hasina falls after 15 years in power

The interim government jailed both Khaleda and Ms Hasina on charges of corruption and abuse of power for about a year before they were both released ahead of a general election in 2008.

Although the BNP boycotted the 2008 election and Khaleda never regained power, the vitriolic feud with Ms Hasina that led to the two being dubbed “the battling Begums” continued to dominate Bangladeshi politics.

Tension between their two parties has often led to strikes, violence and deaths, impeding economic development for a poverty-stricken country of nearly 170 million that is low-lying and prone to devastating floods.

In 2018, Khaleda, her eldest son and aides were convicted of stealing some US$250,000 (S$331,000) in foreign donations received by an orphanage trust set up when she was last prime minister, charges that she said were part of a plot to keep her and her family out of politics.

She was jailed but released in March 2020 on humanitarian grounds as her health deteriorated. She has remained under house arrest since then.

REUTERS

New Delhi

Edited By: Riya Teotia

Updated: Aug 06, 2024

The exiled writer, known for her writing on women’s oppression, blamed Hasina for allowing "Islamists to grow" and letting those involved in corruption to thrive. She also spoke against Army rule in her country and batted for democracy. Photograph:(Twitter)

Story highlights

As former Bangladesh premier Sheikh Hasina escaped the violent student-led protest on Monday (Aug 5), Nasreen took to X to remind people how she was forced to leave Bangladesh in 1994 due to religious politics over her writings.

After Sheikh Hasina’s ouster, exiled Bangladesh writer Taslima Nasreen took a sly dig at Hasina over her previous attempts at “pleasing Islamists” that eventually led to her fall.

]

As former Bangladesh premier Sheikh Hasina escaped the violent student-led protest on Monday (Aug 5), Nasreen took to X to remind people how she was forced to leave Bangladesh in 1994 due to religious politics over her writings. She came back to her country in 1999 to meet her ailing mother, when Hasina was the Prime Minister of Bangladesh.

As former Bangladesh premier Sheikh Hasina escaped the violent student-led protest on Monday (Aug 5), Nasreen took to X to remind people how she was forced to leave Bangladesh in 1994 due to religious politics over her writings. She came back to her country in 1999 to meet her ailing mother, when Hasina was the Prime Minister of Bangladesh.

"Hasina in order to please Islamists threw me out of my country in 1999 after I entered Bangladesh to see my mother on her deathbed and never allowed me to enter the country again. The same Islamists have been in the student movement who forced Hasina to leave the country today," Nasreen wrote on X.

Hasina had to flee to India in a military plane yesterday as protestors stormed her official residence in Dhaka. She is now likely to fly to London to seek asylum in the UK.

The exiled writer, known for her writing on women’s oppression, blamed Hasina for allowing "Islamists to grow" and letting those involved in corruption to thrive. She also spoke against Army rule in her country and batted for democracy.

"Hasina had to resign and leave the country. She was responsible for her situation. She made Islamists to grow. She allowed her people to be involved in corruption. Now Bangladesh must not become like Pakistan. Army must not rule. Political parties should bring democracy & secularism," she said in an earlier post.

Why Taslima Nasreen was forced to leave Bangladesh in 1994?

Taslima Nasreen, a critic of religious fanaticism, gained global attention at the beginning of the 1990s. She wrote several essays and novels with feminist viewpoints, for which she faced criticism in her country

Also Read | Sajeeb Wazed, son of former PM Hasina, tells WION: "Bangladesh will be the next Pakistan"

Nasreen had to leave Bangladesh in 1994 in the wake of multiple death threats of fatwas against her from fundamentalist outfits over her book “Lajja”. Khaleda Zia, the jailed arch-rival of Hasina, was the prime minister then.

The 1993 book was banned in Bangladesh but later became a bestseller elsewhere.

Many of Nasreen’s books - comprising Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal - are still blacklisted and banned in the Bengal region.

(With inputs from agencies)

)

Riya Teotia

Riya is a senior sub-editor at WION and a passionate storyteller who creates impactful and detailed stories through her articles. She likes to write on defence

No comments:

Post a Comment