By AFP

August 28, 2024

Pavel Durov, co-founder of encrypted messaging app Telegram, was arrested at an airport near Paris - Copyright GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA/AFP Steve Jennings

Julia Pavesi and Stuart Williams

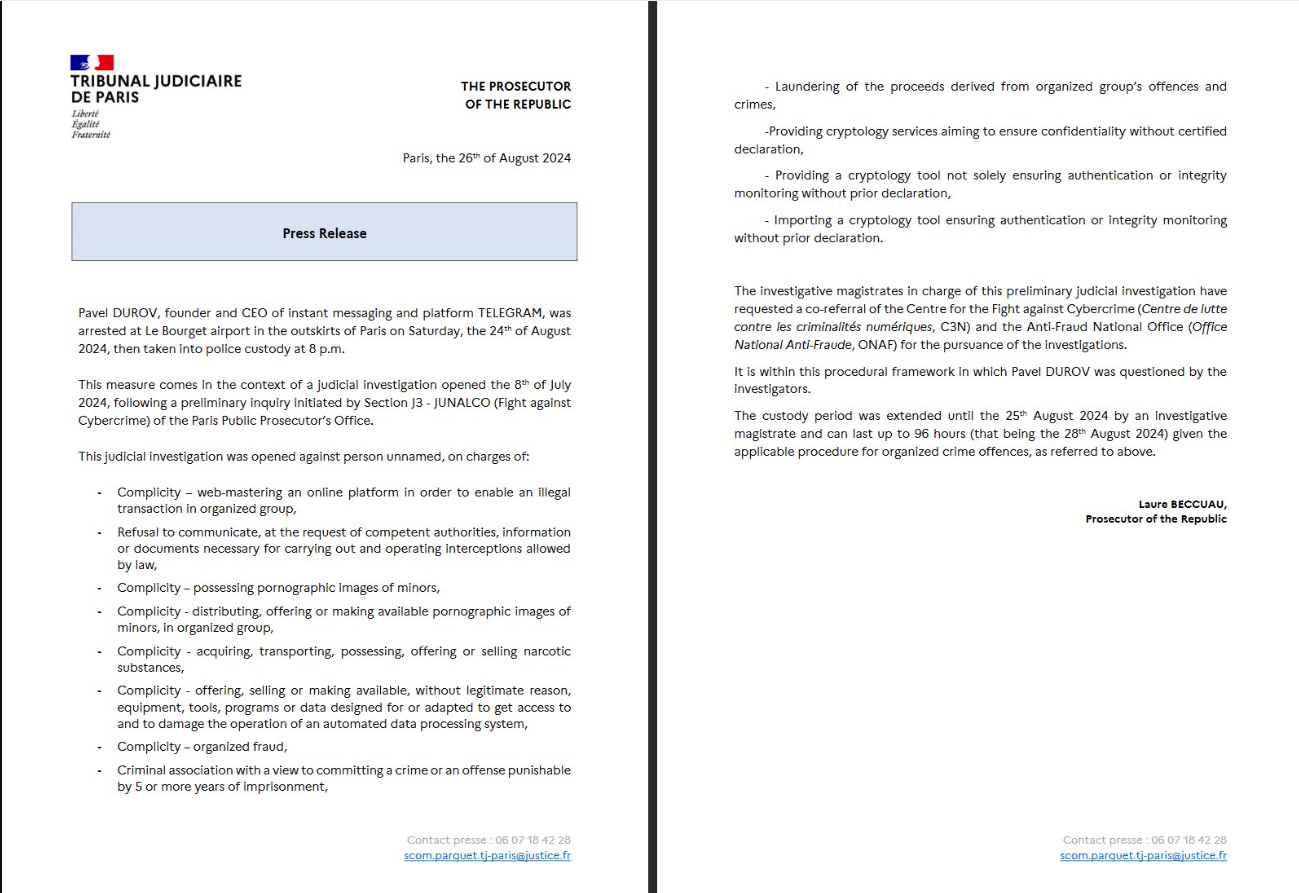

Pavel Durov, the founder and chief of Telegram, is set to learn Wednesday whether he will face charges and even be remanded in custody after his weekend arrest by French authorities over alleged violations at the messaging app.

Durov, 39, was arrested at Le Bourget airport outside Paris late Saturday, and while the judicial authorities have repeatedly extended his initial period of detention, it can last a maximum of 96 hours.

As part of a probe that was confidentially opened on July 8, Durov is being investigated on suspicion of 12 offences related to failing to curb extremist content on Telegram, sources close to the investigation have said.

The tech mogul founded Telegram as he was in the process of quitting his native Russia a decade ago. Its growth has been exponential, with the app now boasting over 900 million users.

An enigmatic figure who rarely speaks in public, Durov is a citizen of Russia, France and the United Arab Emirates, where Telegram is based.

Forbes magazine estimates his current fortune at $15.5 billion, though he proudly promotes the virtues of an ascetic life that includes ice baths and not drinking alcohol or coffee.

Numerous questions have been raised about the timing and circumstances of Durov’s detention, in particular why he flew into Paris apparently knowing a warrant had been issued against him.

– ‘In no way political’ –

In a post on X to address what he called “false information” concerning the case, French President Emmanuel Macron said Durov’s arrest “took place as part of an ongoing judicial investigation”.

“It is in no way a political decision. It is up to the judges to rule on the matter,” he wrote in a highly unusual comment on a legal case.

In Moscow, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said the charges were very serious and thus needed “no less serious evidence”.

“Otherwise this would be a direct attempt to restrict freedom of communication, and, I might even say, directly intimidate the head of a large company,” he said.

The UAE meanwhile said it was “closely following the case” and had requested consular access for its citizen.

Among those voicing support for Durov is fellow tech tycoon and chief executive of X, Elon Musk, who has posted comments under the hashtag #FreePavel.

– ‘Nothing to hide’ –

When the initial 96-hour questioning period ends, the investigating magistrate can either free Durov or press charges and remand him in custody.

He could also be freed under judicial control that could include restrictions on his movements.

Durov, who has been based in Dubai in recent years, arrived in Paris from the Azerbaijani capital Baku and was planning to have dinner in the French capital, a source close to the case said.

He was accompanied by a bodyguard and a personal assistant who always travel with him, added the source, asking not to be named.

Russian President Vladimir Putin was in Baku on a state visit to Azerbaijan on August 18 and 19, though Peskov has denied that the two met.

France’s OFMIN, an office tasked with preventing violence against minors, issued an arrest warrant for Durov in a preliminary investigation into alleged offences including fraud, drug trafficking, cyberbullying, organised crime and promotion of terrorism.

Telegram said in response that “Durov has nothing to hide and travels frequently in Europe”.

“Telegram abides by EU laws, including the Digital Services Act — its moderation is within industry standards,” it added.

“It is absurd to claim that a platform or its owner are responsible for abuse of that platform.”

Telegram has positioned itself as a “neutral” alternative to US-owned platforms, which have been criticised for their commercial exploitation of users’ personal data.

It has also played a key role since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, used actively by politicians and commentators on both sides of the war.

But critics accuse it of hosting often illegal content ranging from extreme sexual imagery to disinformation and narcotics services.

By Craig Murray

TechCrunch - 577180975RR090_TechCrunch_D. Flickr.

The detention of Pavel Durov is being portrayed as a result of the EU Digital Services Act. But having spent my day reading the EU Services Act (a task I would not wish upon my worst enemy), it does not appear to me to say what it is being portrayed as saying.

EU Acts are horribly dense and complex, and are published as “Regulations” and “Articles”. Both cover precisely the same ground, but for purposes of enforcement the more detailed “Regulations” are the more important, and those are referred to below. The “Articles” are entirely consistent with this.

So, for example, Regulation 20 makes the “intermediary service”, in this case Telegram, only responsible for illegal activity using its service if it has deliberately collaborated in the illegal activity.

Providing encryption or anonymity specifically does not qualify as deliberate collaboration in illegal activity.

(20) Where a provider of intermediary services deliberately collaborates with a recipient of the services in order to undertake illegal activities, the services should not be deemed to have been provided neutrally and the provider should therefore not be able to benefit from the exemptions from liability provided for in this Regulation. This should be the case, for instance, where the provider offers its service with the main purpose of facilitating illegal activities, for example by making explicit that its purpose is to facilitate illegal activities or that its services are suited for that purpose. The fact alone that a service offers encrypted transmissions or any other system that makes the identification of the user impossible should not in itself qualify as facilitating illegal activities.

And at para 30, there is specifically no general monitoring obligation on the service provider to police the content. In fact it is very strong that Telegram is under no obligation to take proactive measures.

(30) Providers of intermediary services should not be, neither de jure, nor de facto, subject to a monitoring obligation with respect to obligations of a general nature. This does not concern monitoring obligations in a specific case and, in particular, does not affect orders by national authorities in accordance with national legislation, in compliance with Union law, as interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European Union, and in accordance with the conditions established in this Regulation. Nothing in this Regulation should be construed as an imposition of a general monitoring obligation or a general active fact-finding obligation, or as a general obligation for providers to take proactive measures in relation to illegal content.

However, Telegram is obliged to act against specified accounts in relation to an individual order from a national authority concerning specific content. So while it has no general tracking or censorship obligation, it does have to act at the instigation of national authorities over individual content.

(31) Depending on the legal system of each Member State and the field of law at issue, national judicial or administrative authorities, including law enforcement authorities, may order providers of intermediary services to act against one or more specific items of illegal content or to provide certain specific information. The national laws on the basis of which such orders are issued differ considerably and the orders are increasingly addressed in cross-border situations. In order to ensure that those orders can be complied with in an effective and efficient manner, in particular in a cross-border context, so that the public authorities concerned can carry out their tasks and the providers are not subject to any disproportionate burdens, without unduly affecting the rights and legitimate interests of any third parties, it is necessary to set certain conditions that those orders should meet and certain complementary requirements relating to the processing of those orders. Consequently, this Regulation should harmonise only certain specific minimum conditions that such orders should fulfil in order to give rise to the obligation of providers of intermediary services to inform the relevant authorities about the effect given to those orders. Therefore, this Regulation does not provide the legal basis for the issuing of such orders, nor does it regulate their territorial scope or cross-border enforcement.

The national authorities can demand content is removed, but only for “specific items”:

51) Having regard to the need to take due account of the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Charter of all parties concerned, any action taken by a provider of hosting services pursuant to receiving a notice should be strictly targeted, in the sense that it should serve to remove or disable access to the specific items of information considered to constitute illegal content, without unduly affecting the freedom of expression and of information of recipients of the service. Notices should therefore, as a general rule, be directed to the providers of hosting services that can reasonably be expected to have the technical and operational ability to act against such specific items. The providers of hosting services who receive a notice for which they cannot, for technical or operational reasons, remove the specific item of information should inform the person or entity who submitted the notice.

There are extra obligations for Very Large Online Platforms, which have over 45 million users within the EU. These are not extra monitoring obligations on content, but rather extra obligations to ensure safeguards in the design of their systems:

(79) Very large online platforms and very large online search engines can be used in a way that strongly influences safety online, the shaping of public opinion and discourse, as well as online trade. The way they design their services is generally optimised to benefit their often advertising-driven business models and can cause societal concerns. Effective regulation and enforcement is necessary in order to effectively identify and mitigate the risks and the societal and economic harm that may arise. Under this Regulation, providers of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines should therefore assess the systemic risks stemming from the design, functioning and use of their services, as well as from potential misuses by the recipients of the service, and should take appropriate mitigating measures in observance of fundamental rights. In determining the significance of potential negative effects and impacts, providers should consider the severity of the potential impact and the probability of all such systemic risks. For example, they could assess whether the potential negative impact can affect a large number of persons, its potential irreversibility, or how difficult it is to remedy and restore the situation prevailing prior to the potential impact.

(80) Four categories of systemic risks should be assessed in-depth by the providers of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines. A first category concerns the risks associated with the dissemination of illegal content, such as the dissemination of child sexual abuse material or illegal hate speech or other types of misuse of their services for criminal offences, and the conduct of illegal activities, such as the sale of products or services prohibited by Union or national law, including dangerous or counterfeit products, or illegally-traded animals. For example, such dissemination or activities may constitute a significant systemic risk where access to illegal content may spread rapidly and widely through accounts with a particularly wide reach or other means of amplification. Providers of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines should assess the risk of dissemination of illegal content irrespective of whether or not the information is also incompatible with their terms and conditions. This assessment is without prejudice to the personal responsibility of the recipient of the service of very large online platforms or of the owners of websites indexed by very large online search engines for possible illegality of their activity under the applicable law.

(81) A second category concerns the actual or foreseeable impact of the service on the exercise of fundamental rights, as protected by the Charter, including but not limited to human dignity, freedom of expression and of information, including media freedom and pluralism, the right to private life, data protection, the right to non-discrimination, the rights of the child and consumer protection. Such risks may arise, for example, in relation to the design of the algorithmic systems used by the very large online platform or by the very large online search engine or the misuse of their service through the submission of abusive notices or other methods for silencing speech or hampering competition. When assessing risks to the rights of the child, providers of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines should consider for example how easy it is for minors to understand the design and functioning of the service, as well as how minors can be exposed through their service to content that may impair minors’ health, physical, mental and moral development. Such risks may arise, for example, in relation to the design of online interfaces which intentionally or unintentionally exploit the weaknesses and inexperience of minors or which may cause addictive behaviour.

(82) A third category of risks concerns the actual or foreseeable negative effects on democratic processes, civic discourse and electoral processes, as well as public security.

(83) A fourth category of risks stems from similar concerns relating to the design, functioning or use, including through manipulation, of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines with an actual or foreseeable negative effect on the protection of public health, minors and serious negative consequences to a person’s physical and mental well-being, or on gender-based violence. Such risks may also stem from coordinated disinformation campaigns related to public health, or from online interface design that may stimulate behavioural addictions of recipients of the service.

(84) When assessing such systemic risks, providers of very large online platforms and of very large online search engines should focus on the systems or other elements that may contribute to the risks, including all the algorithmic systems that may be relevant…

This is very interesting. I would argue that under Article 81 and 84, for example, the blatant use of both algorithms limiting reach and plain blocking by Twitter and Facebook, to promote a pro-Israeli narrative and to limit pro-Palestinian content, was very plainly a breach of the EU Digital Services Directive by deliberate interference with “freedom of expression and information, including media freedom and pluralism”.

The legislation is very plainly drafted with the specific intent of outlawing the use of algorithms to interfere with freedom of speech and public discourse in this way.

But it is of course a great truth that the honesty and neutrality of prosecution services is much more important to what actually happens in any “justice” system than the actual provisions of legislation.

Only a fool would be surprised that the EU Digital Services Act is being shoehorned into use against Durov, apparently for lack of cooperation with Western intelligence services and being a bit Russian, and is not being used against Musk or Zuckerberg for limiting the reach of pro-Palestinian content.

It is also worth noting that Telegram is not considered to be a very large online platform by the EU Commission who have to date accepted Telegram’s contention that it has less than 45 million users in the EU, so these extra obligations do not apply.

If we look at the charges against Durov in France, I therefore cannot see how they are in fact compatible with the EU Digital Services Act.

Unless he refused to remove or act over specific individual content specified by the French authorities, or unless he set up Telegram with the specific intent of facilitating organised crime, I do not see how Durov is not protected under Articles 20 and 30 and other safeguards found in the Digital Services Act.

The French charges appear however to be extremely general and not to relate to particular specified communications. This is an abuse.

What the Digital Services Act does not contain is a general obligation to hand over unspecified content or encryption keys to police forces or security agencies. It is also remarkably reticent on “misinformation”.

Regulations 82 or 83 above obviously provide some basis for “misinformation” policing, but the Act in general relies on the rather welcome assertion that regulations governing what speech and discourse is legal should be the same offline as online.

So in short, the arrest of Pavel Durov appears to be pretty blatant abuse and only very tenuously connected to the legal basis given as justification. This is simply a part of the current rising wave of authoritarianism in western “democracies”.

Free speech and ‘homeland’: Moscow's ‘opportunistic’ response to Telegram boss Durov’s arrest

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on Tuesday said relations with France are at their “lowest” level following the arrest of Telegram CEO Pavel Durov at an airport outside Paris on Saturday. The arrest has prompted a stream of condemnations from those in power in Russia – even though the Kremlin itself tried to ban Telegram in 2018.

Issued on: 27/08/2024

French judicial authorities late Monday extended the detention of Durov, who co-founded the popular messaging app, for up to 48 hours. The Paris prosecutor’s office on the same day stated that Durov had been arrested as part of an ongoing probe into crimes related to child pornography, drug trafficking and fraudulent transactions on the platform.

In Russia, an unlikely mix of voices have been speaking up in support of Durov. Some in the political opposition and some from circles close to President Vladimir Putin are condemning the arrest of the tech mogul, who was born in Russia in 1984.

Russian political activist Georgy Alburov described the arrest as “profoundly unfair” in an article published Sunday in The Moscow Times. Alburov, one of the lead investigators in the late Kremlin foe Alexei Navalny’s anti-corruption foundation, said Durov’s arrest is a “significant blow to freedom of speech”, according to the anglophone news site.

The Kremlin has had a similar response. Lavrov’s comment on Tuesday came after Kremlin spokesman Dmity Peskov said that France had levelled “very serious” charges against Durov “that require no less serious evidence”.

“Otherwise, this would be a direct attempt to restrict freedom of communication,” said Peskov, who also warned Paris against trying to intimidate Durov.

Foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova criticised the arrest as symptomatic of how “liberal dictatorships” undercut commitments to human rights “when it suits them” in an interview with a Russian state broadcaster, The Moscow Times reported on Sunday. A deputy vice president of the lower-house Duma, Vladislav Davankov, joined a rally outside the French embassy in Moscow to demand the release of Durov.

Across the spectrum

“The most fascinating aspect (of the immediate aftermath of Durov’s arrest) was the spectrum of those who promptly came to his defence,” wrote the US-based Russian economist Konstantin Sonin in a Moscow Times opinion piece published on Monday. Sonin noted that “Russian military bloggers, worried about the potential for the West to access Telegram’s secrets, joined the chorus of (Durov) supporters”.

At first glance, the pro-Durov stance in Russian opposition circles may seem the more logical. The career path of Telegram's 39-year-old founder, whose fortune Forbes estimates at more than $15 billion, looks more like one of a dissident than a pro-Putin oligarch.

Durov launched his career as a mogul by co-founding VKontakte, the Russian equivalent of Facebook, with his brother in 2006. They refused to provide the government with access to user data, according to Mariëlle Wijermars, an assistant professor in internet governance at Maastricht University.

A tug-of-war with the Kremlin eventually led the young Russian entrepreneur to relinquish the reins of VKontakte in 2013 to wealthy businessmen close to Putin. Durov then opted for exile and found refuge in Dubai, where he launched Telegram the same year. The co-founder presented the new messaging service as the ultimate weapon against state censorship.

Durov’s early career enabled him “to gain a certain amount of trust among Russians. His charisma and style of speaking contributed to the migration of some Russian internet users” to Telegram, said Ksenia Ermoshina, a specialist in the Russian internet at the Centre for Internet and Society at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

A self-billed haven for freedom of expression, Telegram eventually attracted the ire of the Kremlin, which seeks to monitor cyberspace. In 2018, the government tried to muzzle the platform, which increased its popularity in Russia.

“The Russians thought that if [Telegram] was blocked, it could be trusted,” said Ermoshina. Ironically, during the period when the platform was blocked (but easily accessible by setting up a virtual private network, or VPN), the number of accounts created by members of the Russian presidential administration and elected representatives multiplied.

Durov's arrest in France should theoretically be a source of satisfaction for a Russian government that has failed to control the man sometimes dubbed the "rebel" or "Robin Hood" of the Russian web.

But that would be ignoring the other side of Telegram's success story. The relationship between the platform and the Kremlin is “more complicated than some might think”, said Jeff Hawn, a Russia specialist at the London School of Economics (LSE). “I would define it as distant but cordial.”

Durov’s “refusal to provide (the government with) information about VKontakte users hews more to his libertarian philosophy than to a political opposition to Vladimir Putin”, the CNRS’s Ermoshina said.

The Telegram boss does not seem to be more cooperative with governments that are less authoritarian than Moscow. In this respect, Durov is more reminiscent of a self-declared free speech absolutist like Elon Musk than a Russian dissident in exile. The owner of X expressed his solidarity with Durov after his arrest.

In Ukraine, where the full-scale Russian invasion led to even more popularity for Telegram, these allegations have caused “growing criticism that Telegram is not as neutral as it used to be”, said Yevgeniy Golovchenko, a Russian disinformation specialist at the University of Copenhagen. “There is fear that [Telegram] may be collaborating with the Russian regime and [some] argue it’s a threat to national security.”

Since the start of the Ukraine war, Durov has been careful not to take a position on the conflict. “He hasn’t come out in favour of the war, but hasn’t spoken against it,” said the LSE’s Hawn.

This is one of the reasons why some close to Putin may have found “a very effective tool for propaganda. [Durov] represents a certain kind of elite who doesn’t want to get involved” in the war, Hawn said.

Russian propagandists have seized on Durov's arrest to try to convey the message that all Russians, wherever they are, “need Russia’s protection”, he said.

'Living without a homeland'

Former Russian prime minister Dmitry Medvedev wrote on Telegram that Durov’s arrest would prove that the tech mogul, who obtained a French passport in 2021, was mistaken to think that “citizenship or residency in other countries” would allow him to “be a brilliant ‘citizen of the world’, living well without a homeland”, the Moscow Times reported. “To all our common enemies now, he is Russian.”

This viewpoint fits perfectly into the narrative Putin has been developing since the war began of a Russia forced to come to the aid of its citizens, wherever they may be.

“[Putin] justified the war in Ukraine by saying it was necessary to protect the Russians in the Donbas,” said Ermoshina.

“It’s a very pragmatic and opportunistic approach to propaganda,” said disinformation specialist Golovchenko. Whatever the Kremlin’s opinion of Durov, by denouncing his arrest, Moscow is “sending the following message to the Russian population and notably the youth: look how France, the country of liberty, treats entrepreneurs”, Ermoshina explained.

French President Emmanuel Macron said Monday on X that Durov’s arrest “took place as part of an ongoing judicial investigation. It is in no way a political decision.”

“There are many people in the Russian establishment, the Russian government (and) the Russian military who are very afraid because Telegram is used very, very widely,” said Wijermars. There is fear that Durov’s arrest “might give France access to all kinds of sensitive information”.

It is thus in Moscow’s interest that his stay in the hands of French justice is as brief as possible.

This article is a translation of the original in French.

After the arrest of Telegram's boss in France, attention is on the messaging app and its hands-off approach to content moderation. Some blame it for inflaming unrest, others see it as a den for criminal activity.

Telegram Messenger, better known as Telegram, is a social media and instant messaging service. For millions of users it is simply a daily tool for communication. For others it is much more than that.

At its most basic level Telegram enables users to chat, and share photos and files for free. It offers end-to-end encryption for voice and video calls. It also lets users post files, use cryptocurrency, have unlimited cloud storage, create groups for up to 200,000 members, or start channels with an unlimited number of subscribers — and untold influence.

As of 2022, it offers a paid subscription version for those who want more features like faster downloads. The company says making money "driven by our users, rather than advertisers or shareholders" lets them stay independent. They promise that private messaging will remain free "no ads, no subscription fees, forever."

Such features and promises have made it a powerful social network throughout much of the world. Some critics have blamed it for inflaming the recent anti-immigrant riots across the UK. Others point to everything from disinformation campaigns aimed at supporters of Ukraine to illegal activities such as drug dealing and weapons smuggling.

What sets Telegram apart?

What makes Telegram different from other apps like WhatsApp is its unrelenting focus on privacy and its strong stance against censorship. This makes it especially popular in places with authoritarian regimes or where people fear eavesdropping. Government opposition groups are big users.

Still others may use Telegram to avoid having their data end up in the hands of Big Tech or advertisers. Some may have been banned from Twitter or Facebook and need a new outlet.

At the beginning of 2024, Telegram had more than 800 million active monthly users, according to numbers crunched by Demand Sage, a data analytics company. That is a huge increase on the 300 million users at the start of 2021.

Demand Sage expects it to reach a billion users by the end of the year. On its own website, Telegram claims to already have over 950 million active users.

In parts of the world, Telegram is the most popular instant-messaging app. India has the most users by far, followed by Russia, Indonesia, the US, Brazil and Egypt. It has been reportedly blocked in China, Iran, Cuba, Thailand and Pakistan.

Supporters demand release of Telegram boss in France 01:49

Where did Telegram come from?

Telegram was founded in St. Petersburg by Russian-born Pavel Durov and his brother, Nikolai, in 2013. Pavel Durov is now chief executive (CEO) of the company.

Before creating Telegram, the pair had started VKontakte, or VK, in 2006. That social platform was a huge success but caught the attention of the Russian authorities. Durov left Russia in 2014 for self-imposed exile, sold his part of VK and took Telegram with him.

After stops in Berlin, London and Singapore, the company's development team is now based in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

But nothing is forever in the digital world, and the company threatens to up sticks anytime: "We're currently happy with Dubai, although are ready to relocate again if local regulations change," their website states.

Why was Telegram's CEO and co-founder arrested?

They may be packing sooner than they thought. On August 24, the 39-year-old billionaire CEO was arrested after his jet touched down at Paris–Le Bourget Airport in France.

Durov's arrest — a first of its kind — was a surpise to many and could be in connection with a French request, or a wider EU request, for not complying with regulations. Details were not given, but most reports point to the company's lack of content moderation and its lack of cooperation with law enforcement authorities.

A company statement on Telegram on Sunday seems to underpin this: "Telegram abides by EU laws … its moderation is within industry standards and constantly improving."

It went on to say that its CEO has nothing to hide and is often in Europe. "It is absurd to claim that a platform or its owner are responsible for abuse of that platform."

Indeed when it comes to moderation or deletion, Telegram policy is quite simple, as it only deals with publicly available content. All chats are private among the participants and the company will not process any requests relating to them.

All this scrutiny is likely unwelcome — at least for now. By bringing attention to Telegram, attention is also being brought to its much-touted promise of security.

Experts point out that messages on Telegram are not automatically end-to-end encrypted; users must choose this option. The app also uses its own encryption tools and doesn't allow these to be tested by anyone on the outside. If its privacy protocols are proven to be lacking, the news could put an end to the company's biggest selling point.

Besides disruption for Telegram's daily operations, Durov's arrest is likely to unsettle users who may question what the company is divulging to get out of jail.

More broadly, by taking on Telegram governments are pushing a discussion about free speech, censorship, free information and control of global digital platforms.

By holding a company founder responsible, authorities are trying to get more control of illegal activity and slow online conspiracy theories, extremism and terrorist recruiting, among other things.

With so much to lose, Telegram is likely to pull out all the stops to hold off more regulation. As the company makes clear, it is ready to move at the drop of a hat. But where to?

Edited by: Uwe Hessler

Timothy Rooks One of DW's team of business reporters, Timothy Rooks is based in Berlin.

No comments:

Post a Comment