UK

Starmer’s Doom and Gloom Risks Eclipsing Labour Message of HopeAlex Wickham, Ailbhe Rea and Irina Anghel

Fri, August 30, 2024

(Bloomberg) -- Keir Starmer faces growing doubts among senior Labour politicians about his administration’s gloomy messaging, after calculated interventions bookending the parliamentary recess focused on the UK’s ailing public finances and the tough measures needed to fix them.

Just before Members of Parliament headed into their summer break, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves signaled taxes will have to rise to fill an unexpectedly large fiscal black hole of £22 billion ($29 billion) left by the previous Conservative government. Just 6 days before MPs return, Starmer warned “things will get worse” before they improve, as his administration grapples with the budgetary void. Rounding out a challenging first two months in office for the premier, Britain was hit by days of far-right rioting between the two speeches.

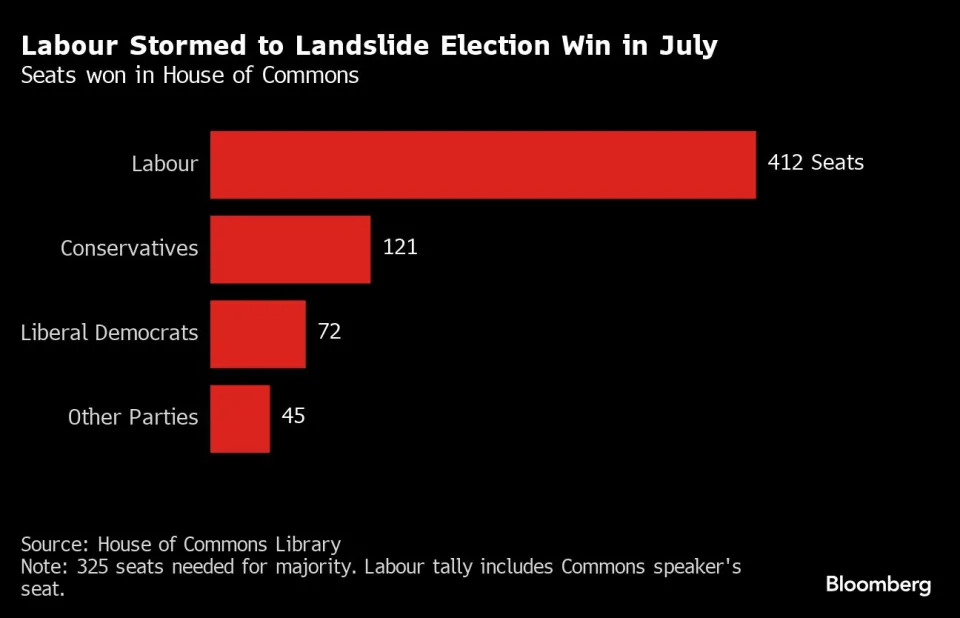

The danger for Starmer is the focus on tough decisions and fiscal rigor risks drowning out the positive message of a party returning to power in a landslide election win after 14 years out of office with a program to improve the lives of working people.

With optimism in short supply, the first rumblings of dissent are already surfacing ahead of Parliament’s return next week. In conversations with Bloomberg, these aides, backbench MPs and ministers — even some in cabinet — questioned whether Downing Street needs to better calibrate its message to highlight plans to turn the country around, rather than risk an overly negative approach that distracts from Labour’s own policies. Otherwise, there’s a danger that the party’s annual conference in three weeks will be dominated by rows about the budget, according to the people, who asked not to be named discussing their private views.

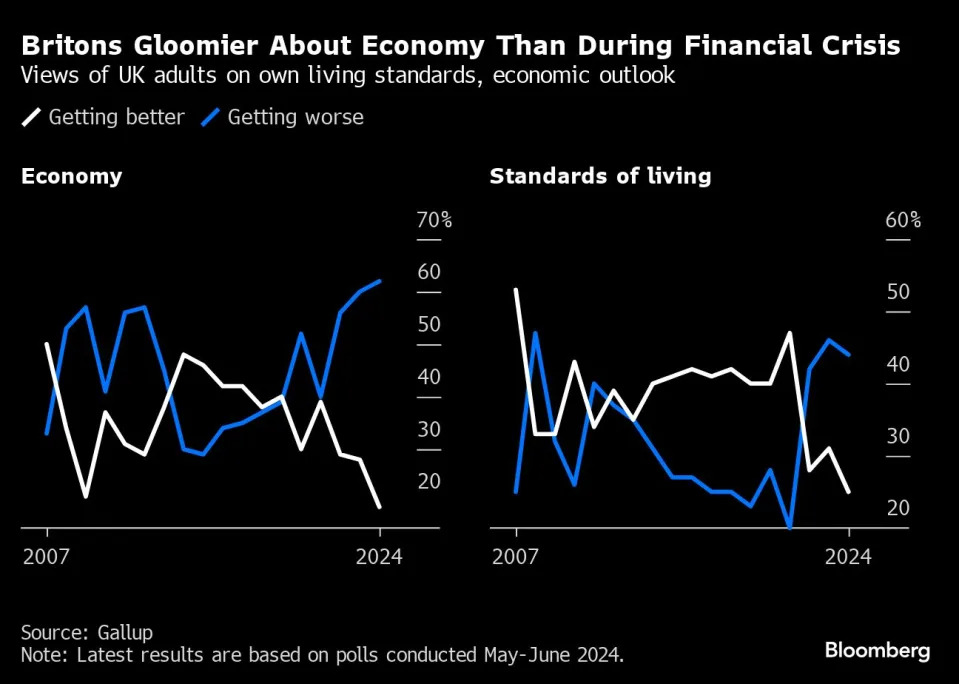

Polling suggests more positivity may be needed. New Gallup data collected during the election and shared with Bloomberg found that Britons were more pessimistic about their economic futures than during the 2009 financial crisis. Some 62% said the economy was getting worse where they lived, compared to just 19% who said it was improving. And a majority of Brits already have a negative view of the new government, according to a YouGov survey released this week.

Starmer is live to the danger.

“This is actually a project of hope,” he told reporters traveling with him to Germany. “But it’s got to start with the hard yards of doing the difficult stuff, of clearing out the rot first.”

Those tough calls are likely to crystallize on Oct. 30, when Reeves delivers her first budget. The doom and gloom camp, as one Labour lawmaker described it, is led by the chancellor, who’s determined to hammer home to the public that she’s been handed a woeful budgetary inheritance by the Tories.

“Many of the same problems that led to the Labour Party’s landslide win in the British election in July are now theirs to solve,” said Benedict Vigers at Gallup.

Reeves’s strategy is seen internally as an extension of the electoral tactics deployed by Starmer’s top aide Morgan McSweeney: a cautious approach to spending and a focus on the political turmoil wrought by the Conservatives. The chancellor views the rhetoric as necessary to show she has no choice but to make unpopular calls, people said.

Starmer is fully signed up to that approach and believes the public want politicians to be up-front with them rather than deploy the false boosterism of former prime minister Boris Johnson, people familiar with his thinking said.

Labour strategists see getting the least popular decisions out of the way early on in the administration as sensible politics. The premier’s allies argue one of his strengths has been choosing a strategy and sticking to it no matter the criticism or distractions, a virtue they see as vindicated by the election win.

“Over the weeks ahead we’ll hear more about not just the tough decisions needed but also the journey the government is embarking on,” Jonathan Ashworth, chief executive of the pro-Starmer Labour Together think tank, said. Starmer could adopt an argument of “prudence for prosperity,” he added.

Others in Labour are unsure. Some lawmakers say Number 10 has given disproportionate airtime to fiscal woes and not enough to conjuring a positive narrative about the government’s first 100 days, from restoring mandatory housing targets and agreeing National Health Service pay deals to unveiling legislation centered around Starmer’s so-called ‘missions’ to improve the country.

There are also concerns that the negativity will only worsen political disillusionment. This argument is seen as an extension of a pre-election clash some MPs had with Starmer and Reeves, who they dubbed the “no machine” for lacking ambition and blocking new policies and spending.

Some early decisions have already proved controversial, and none more so than Reeves’s surprise decision to remove winter fuel payments from pensioners. Some Treasury officials had doubts over the politics of the policy beforehand, but Reeves insisted it was necessary to help balance the books, people familiar with the matter said. But the decision to means-test the benefit landed worse than expected, leading to efforts to mitigate the impact without conducting a full-scale U-turn.

Others describe early evidence of hubris by Downing Street in making a series of quick decisions after winning power without thinking them through. They cite a recent cronyism row involving civil service appointments and a government pass awarded to a donor.

Further policy concerns cited by Labour MPs include Reeves’s orders for departments to find billions of pounds in savings, scrapping a cap on self-funded social care spending without a policy to replace it, and a lack of plans to abolish a policy limiting child benefit to a family’s first two children.

There are also fears among lawmakers that the chancellor may raise taxes that don’t just hit the rich, such as fuel duty, while the biggest concern is she will say she has to implement welfare cuts. Some MPs feel Reeves boxed herself in by promising to keep in place Tory cuts to the national insurance payroll tax, saying she could have avoided a lot of pain elsewhere by reversing them.

One lawmaker said they saw the problem as Starmer letting Reeves run the show on the economy, without the premier having an overarching positive political story to tell.

“Everybody in Britain is willing to sacrifice for a purpose,” said John McTernan, a former adviser to Tony Blair and strategist for BCW Global. “What’s going to get better is the bit that needs to be vividly brought to life.”

Bloomberg Businessweek

Will things get worse like Keir Starmer says?

Ben King - Business reporter, BBC News

Fri, August 30, 2024

[EPA]

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has warned that "things will get worse before they get better".

He has been hammering home the argument that the Labour Party has taken over from the Conservatives at a time when the government is short of money, and public services such as health and prisons are in a mess.

He is claiming things are worse than he and his party knew before they won the election – so they will have to do things to fix them which they didn’t warn about before people voted.

The Conservatives say that Labour has planned to raise taxes all along.

How did we get to this point?

The PM's speech didn’t spell out exactly what bad news could be coming, but it did warn of a "painful" budget on 30 October.

This is when the government will announce its plans for taxation and spending over the coming year.

The government is definitely short of money. This is partly the result of weak economic growth in recent years, which has meant companies are making lower profits, and people’s earnings are growing more slowly.

That means the taxes the government collects on wages, profits and purchases have also been growing more slowly.

At the same time, an ageing society has placed a greater burden on public services such as the NHS.

The government’s spending watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, has also said that the decision to leave the European Union has slowed economic growth.

But Labour argues that things are even worse than they seemed before the election. The prime minister has warned of a so-called "black hole" in the public finances.

All of the above rhetoric on the state of the economy might be used in attempts to justify any decisions to raise taxes or other measures which were not set out during the election campaign.

The PM's speech didn’t spell out exactly what bad news could be coming, but it did warn of a "painful" budget on 30 October.

This is when the government will announce its plans for taxation and spending over the coming year.

The government is definitely short of money. This is partly the result of weak economic growth in recent years, which has meant companies are making lower profits, and people’s earnings are growing more slowly.

That means the taxes the government collects on wages, profits and purchases have also been growing more slowly.

At the same time, an ageing society has placed a greater burden on public services such as the NHS.

The government’s spending watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, has also said that the decision to leave the European Union has slowed economic growth.

But Labour argues that things are even worse than they seemed before the election. The prime minister has warned of a so-called "black hole" in the public finances.

All of the above rhetoric on the state of the economy might be used in attempts to justify any decisions to raise taxes or other measures which were not set out during the election campaign.

What does 'getting worse' actually mean?

In his speech on Tuesday, Sir Keir set out a number of areas where he says the country is not working well such as NHS waiting lists, a lack of capacity in prisons and sewage discharges by water companies.

He is warning that these problems will not be resolved quickly.

But he is also warning that fixing those and other problems will cost money.

That could mean a combination of tax rises and spending cuts. In the prime minister's words, it will be "painful".

However, it is not inevitable that the next Budget has to be, or will be, painful.

Labour's decision to settle industrial action by giving public sector workers pay rises, and to limit the amount of money the government borrows, has increased the pressure on the public finances.

There is also a clear political strategy at work here, with Labour looking to heap as much blame as possible for unpopular decisions on the previous government while they are new in power.

[PA Media]

In his speech on Tuesday, Sir Keir set out a number of areas where he says the country is not working well such as NHS waiting lists, a lack of capacity in prisons and sewage discharges by water companies.

He is warning that these problems will not be resolved quickly.

But he is also warning that fixing those and other problems will cost money.

That could mean a combination of tax rises and spending cuts. In the prime minister's words, it will be "painful".

However, it is not inevitable that the next Budget has to be, or will be, painful.

Labour's decision to settle industrial action by giving public sector workers pay rises, and to limit the amount of money the government borrows, has increased the pressure on the public finances.

There is also a clear political strategy at work here, with Labour looking to heap as much blame as possible for unpopular decisions on the previous government while they are new in power.

[PA Media]

Is there really a 'black hole' in the public finances?

The phrase "black hole" often appears in discussions about government and money, and it means different things.

In this case, Chancellor Rachel Reeves and the prime minister are talking about a gap between what government departments, such as health and education, expected to spend this year versus what they will actually end up spending.

This gap was first mentioned by Ms Reeves in July, when she said the government was overspending by £22bn - and claimed it had been "covered up" by the Conservatives before the election.

Shadow chancellor Jeremy Hunt has meanwhile accused Ms Reeves of an "utterly bogus attempt to hoodwink the public".

There is a debate about how much of a surprise this was. About £9bn of the £22bn is the cost of increasing public sector pay above the 2% which had been budgeted for - a choice which has been made by this new government.

Paul Johnson, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies thinktank, has argued that the need to give higher public sector pay rises could easily have been foreseen.

But other items which make up the £22bn were more genuine surprises, he says, including that it was not clear that reserve money seemingly expected to cover higher spending on the asylum system had already been, in effect, spent elsewhere.

He and other experts have argued that neither Tories nor Labour were straightforward with the public during the election campaign about how bad the public finances were, and what unpopular measures are required to fix it.

The phrase "black hole" often appears in discussions about government and money, and it means different things.

In this case, Chancellor Rachel Reeves and the prime minister are talking about a gap between what government departments, such as health and education, expected to spend this year versus what they will actually end up spending.

This gap was first mentioned by Ms Reeves in July, when she said the government was overspending by £22bn - and claimed it had been "covered up" by the Conservatives before the election.

Shadow chancellor Jeremy Hunt has meanwhile accused Ms Reeves of an "utterly bogus attempt to hoodwink the public".

There is a debate about how much of a surprise this was. About £9bn of the £22bn is the cost of increasing public sector pay above the 2% which had been budgeted for - a choice which has been made by this new government.

Paul Johnson, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies thinktank, has argued that the need to give higher public sector pay rises could easily have been foreseen.

But other items which make up the £22bn were more genuine surprises, he says, including that it was not clear that reserve money seemingly expected to cover higher spending on the asylum system had already been, in effect, spent elsewhere.

He and other experts have argued that neither Tories nor Labour were straightforward with the public during the election campaign about how bad the public finances were, and what unpopular measures are required to fix it.

How would a government fill a 'black hole'?

Governments faced with a gap between what they plan to spend and what they expect to raise in taxes face a choice.

They could cut spending, raise taxes, or cover the gap by borrowing money, however, the new Labour government has chosen to impose a limit on how much it can continue borrowing.

It says that the total size of the national debt (relative to the size of the economy) has to be projected to fall in five years’ time. This is the same limit as the previous Conservative government set itself under what are known as "fiscal rules".

Fiscal rules are self-imposed by governments in most rich countries to maintain credibility with financial markets.

The government is very close to breaking this rule. Latest figures suggest it is within £9bn of that limit - which is next to nothing given the scale of government spending.

Ms Reeves has very little scope to raise borrowing and stick within this target. So it is likely that she will raise taxes and announce some spending cuts in the forthcoming Budget.

Which taxes will go up?

The chancellor has said more about what taxes will not be going up – that includes the four taxes which raise the most: income tax, National Insurance, VAT, and corporation tax, which are charged on company profits.

Labour promised not to raise taxes on "working people", and that those with the "broadest shoulders" (i.e. wealthy people) should bear the burden.

In ruling out raising the biggest taxes, Labour has limited its room to manoeuvre when it comes to raising more money.

Some tax rises have been announced – such as a decision to charge VAT on private school fees. But the amounts raised would fall short of what will be needed to cover the gap.

Some options which have not been ruled out include increasing taxation of pensions, capital gains (a tax on profits made when a person sells an asset), or inheritance tax.

A number of independent experts have argued that the fiscal rules are not the best way to set out a path for government spending, and that the measures the government has to do to meet them are not necessarily the best decisions.

Labour will ‘take a hammer’ to public services, Flynn to say

Craig Paton, PA Scotland Deputy Political Editor

Fri, August 30, 2024 a

The UK Government will “take a hammer to public services”, the SNP’s Westminster leader is expected to say on Saturday.

Stephen Flynn will address delegates at his party’s conference in Edinburgh, his first major speech to members since losing dozens of MPs in last month’s election.

The Aberdeen South MP is expected to use the speech to criticise the new Government over the economy.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer said the Budget in October will be “painful”, while Chancellor Rachel Reeves claimed the previous Tory government hid a more than £20 billion black hole in public finances.

“You will all know that one of the oldest saying in politics is that you campaign in poetry and govern in prose,” he is expected to tell delegates.

“Labour has gone one step further – campaign in poetry and govern painfully.

“From the poetic promise of change to things can only get worse.

“Taking a hammer to public services seems apt for a toolmaker’s son.”

Mr Flynn will also issue a call to his own party, telling members they “must offer hope in the face of Labour Party austerity cuts and misery”.

“Our argument, our belief and our offer to the Scottish people is that Brexit Britain is not as good as it gets,” he will add.

“We believe that decisions made in Scotland, for Scotland can deliver a better future for all.

“That becoming a normal independent country in Europe can meet our people’s needs and their aspirations.

“That it can deliver the basic belief that the next generation can and should aspire to a higher standard of living and a better quality of life than that which has gone before.

“Those are simple things, but they are the most important of all.”

Scottish Conservative finance spokeswoman Liz Smith MSP, said: “Stephen Flynn is taking the public for fools.

“As the Scottish Fiscal Commission pointed out this week, the SNP is to blame for the mess in Scotland’s finances so they cannot be the solution.

“Despite receiving record block grants from Westminster and imposing the highest taxes in the UK, the SNP have run our public services into the ground and created a huge black hole in Scotland’s finances.

“Yes, Labour have betrayed pensioners by ditching universal winter fuel payments while agreeing above-inflation public sector pay deals – but the SNP have done exactly the same thing in Scotland.”

Scottish Labour deputy leader Jackie Baillie said: “The party responsible for the cuts we are seeing in Scotland right now is the SNP and no amount of spin can hide that.

“The SNP’s cynical and dishonest election campaign was rejected by Scottish voters, but it is still sticking to the same script.

“Labour is working to clean up the mess the Tories left behind and renew our country – including setting up GB Energy here in Scotland, making work pay and prioritising economic growth.

“It’s time for the SNP to stop making excuses and set out how it will fix the mess it has made of Scotland’s public services and public finances.”

He never promised us a rose garden – but Keir Starmer’s ‘doom and gloom’ speech was partisan finger pointing

Peter Bloom, Professor of Management, University of Essex

Thu, August 29, 2024

In a recent speech, British prime minister Keir Starmer vowed to fix the “rotten foundations” of the country. Addressing an audience of workers and public servants invited to the garden of 10 Downing Street, Starmer positioned his government as one of service, promising to tackle the deep-seated issues plaguing Britain.

“When there is deep rot in the heart of a structure, you can’t just cover it up,” Starmer declared. The message was that Britain needs fundamental change rather than quick fixes.

Starmer painted a grim picture of the state of the nation. He cited a £22 billion black hole in public finances as “the inheritance the last government left us”. Speaking of how he planned to deliver justice following shocking scenes of civil unrest, he drew parallels between the recent riots and those of 2011, arguing that the situation has worsened to the extent that he didn’t know if there was room in prisons to house the people being convicted.

He even suggested, without evidence, that people went out to cause violence because they knew they probably wouldn’t be punished. “They saw the cracks in our society after 14 years of populism and failure – and they exploited them,” he claimed.

Starmer’s diagnosis of Britain’s problems will resonate with many but his approach risks oversimplifying complex issues. By framing the country’s challenges primarily as the result of recent Conservative governance, Starmer overlooks the deeper, more entrenched ideological foundations that have contributed to these problems over decades.

Starmer’s speech was powerful in its imagery of rot and decline but he faces a significant challenge in translating rhetoric into meaningful action. The Labour party’s historical complicity in promoting the neoliberal policies that helped bring the country to its current state cannot be ignored when we talk of “rotten foundations”.

In the 1990s, under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, Labour embraced many aspects of the neoliberal economic model, including privatisation of public services and a light-touch approach to financial regulation. Starmer might want to find a new economic model but is, as of yet, taking little action to bring one to life. The promised Great British Energy and railway nationalisation would barely scratch the surface in terms of reversing decades of privatisation – including in key sectors such as prisons, healthcare and probation.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

The irony of Starmer’s position becomes even more apparent when we consider Labour’s historical role in shaping public perception of economic alternatives. Starting with Blair’s “third way”, Labour has played a significant part in framing critiques of neoliberalism as politically unfeasible and economically irresponsible. Blair’s approach, presented as pragmatic and non-radical, effectively narrowed the scope of acceptable political discourse.

This strategy did yield some short-term gains, yet it simultaneously helped entrench the very “rotten foundations” Starmer now decries. Blair made it difficult for subsequent Labour leaders, including Starmer, to propose fundamental changes without facing accusations of extremism or economic recklessness.

Fiscal rules

Starmer’s task is further complicated by Labour’s recent political strategy. He and his chancellor, Rachel Reeves, bound themselves to restrictive fiscal rules in order to appear “electable”, even in the face of a public crying out for significant change. Now they have hardly any levers to pull to turn things around.

Starmer finds himself in a paradoxical position: railing against a system that his own party helped to normalise and defend. This legacy presents a significant challenge to any genuine attempt at addressing the deep-seated issues in British society and economy.

A partisan approach, while politically expedient, may ultimately hinder progress towards addressing the systemic issues facing the UK. By focusing heavily on the failures of recent Conservative governments, Starmer misses an opportunity to engage in a more nuanced discussion about the structural changes needed to address Britain’s challenges.

A more constructive approach would involve acknowledging the complex interplay of historical, economic and political factors that have led to the current situation. This could include recognising the role of both major parties in shaping economic policies and addressing the limitations of the neoliberal economic model in ensuring equitable growth and social cohesion.

Starmer’s speech does hint at some awareness of these complexities. He speaks of making “unpopular decisions” for the long-term good of the country and warns of short-term pain. However, without a more comprehensive critique of the underlying economic system, these sacrifices risk being seen as merely austerity by another name.

Indeed, given his focus on the social unrest and the failures it exposed in the justice system, Starmer’s speech missed an opportunity to offer the kind of truly progressive vision for criminal justice reform that had been implied by his appointment of James Timpson as a prisons minister.

Instead he packaged up the state of Britain’s prisons with a long list of other problems the Conservatives left him. We learnt that Starmer doesn’t “want” to release prisoners early but had to because of the Conservatives.

Instead of acknowledging the root causes of social unrest, including economic inequality and lack of opportunity, he bundled his response in with warnings of austerity-like measures to come. He risks perpetuating a cycle of social unrest and punitive responses, rather than fostering the transformative change needed to create a more just and equitable society.

His approach to addressing Britain’s “rotten foundations” inadvertently traps him in a narrative of doom and gloom. By embracing a more nuanced critique, beyond partisan finger pointing, that acknowledges Labour’s historical role in shaping these foundations, Starmer could have crafted a more hopeful and forward-looking message. This would not only offer a path for genuine systemic change but also provide a compelling vision for voters.

Starmer’s commitment to addressing Britain’s fundamental problems is commendable, however, his current rhetorical approach risks perpetuating the very partisan divisions he seeks to overcome. The challenge for Starmer and Labour is to find a way to critique the failures of recent governments while also honestly acknowledging their own role in creating these systemic problems.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Peter Bloom does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Starmer’s speech: Labour is now promising misery instead of change

His speech on Tuesday underlined that working class people cannot rely on the Labour government

Keir Starmer’s “change” for the worse will be shouldered by working people

Keir Starmer’s “change” for the worse will be shouldered by working people

(Photo: Flickr/ Keir Starmer)

By Isabel Ringrose

Monday 26 August 2024

Monday 26 August 2024

SOCIALIST WORKER Issue 2920

Keir Starmer—the supposed bringer of “change”—made a speech on Tuesday that life in Britain “is going to get worse”. Not just worse, but “worse than we ever imagined”.

In his first keynote speech, which set out the government’s perspective, Starmer posed as a friend of the people by “being honest” about “the choices we face”.

Starmer wants to seem like a responsible adult, who you can trust to fix the “rot set deep in the heart” of the country at the hands of the Tories.

He is vowing to fix the “rubble and ruin” left by successive Tory governments. And, like chancellor Rachel Reeves, he’s claiming that the Conservatives hid the true financial picture. But who will pay for this rot, rubble and ruin?

The speech was billed as “a direct message to the working people across Britain”. It is cover for Labour to not do all the things it said it would—and do what it said it wouldn’t.

Its first budget is due on 30 October, so the government is scrambling to set the scene about how ordinary people will pay the price for capitalist crisis.

That’s evident in its first broken promise in power—that energy bills will decrease.

Instead energy bills are set to increase by 10 percent in the run-up to winter, equivalent to £12 a month.

That’s thanks to Labour allowing the industry regulator to increase the cap on gas and electricity from October.

Under the new price cap, the average dual-fuel energy bill will rise to £1,717 a year, up £149 from its current level of £1,568 in place since July. The cap is set every quarter by Ofgem.

Ofgem chief executive Jonathan Brearley has put the burden on consumers to “shop around” to keep warm this winter.

The regulator revealed the cap after Reeves set out plans to restrict the winter fuel allowance that helps pensioners pay their bills.

This will no longer be universal to those claiming a state pension and only pensioners on means-tested benefits would qualify this winter. Reeves is trying to close up a “black hole” in the public finances she blames on the Tories. But benefits to pensioners should not be up for grabs.

The allowance is worth between £100 and £300 and paid to 11.4 million pensioners in 8.4 million households in 2022-23 in England and Wales.

Now payments worth £200 will be made to households receiving pension credits, or £300 to households on pension credits paid to someone over 80.

Millions of pensioners will face higher energy costs and colder winters as part of a plan to save £22 billion. But this is at the cost of freezing pensions who have to choose between food and heating—and in some cases won’t be able to choose either.

Starmer’s speech this week demonstrates how these vicious cuts are not the end of the attacks, but the beginning.

There needs to be proper resistance every time the government tries to axe jobs, drop benefits and slash services. It is possible to fight off these attacks but it must start now.

Where is Keir Starmer’s Great British Energy?

The Labour government planned to introduce a state energy company called Great British Energy to lower costs.

It would invest in renewable energy and own, manage and operate clean power projects.

It’s yet to get going. Meanwhile energy secretary Ed Miliband said, “The rise in the price cap is a direct result of the failed energy policy we inherited.

“The only solution to get bills down and greater energy independence is the government’s mission for clean, homegrown power.”

Labour can blame the Tories all it wants, but without regulation on privatised energy bills prices will continue to hike and leave ordinary people with less and less.

And while Labour postures over who to blame, it’s pensioners that will suffer. Simon Francis, coordinator of the End Fuel Poverty Coalition, called it a “cruel decision.”

He said more vulnerable people succumb to health complications from living in cold and damp conditions. He estimates that Labour’s savings will be wiped out by additional strain on the health service.

Fuel cut is ‘reckless’—Age UK

Age UK said that two million pensioners who need the payments will no longer get them.

Caroline Abrahams, Charity Director at Age UK, described the situation as “reckless and wrong”.

“Means-testing Winter Fuel Payment when fuel prices are rising by 10 percent spells disaster for pensioners on low and modest incomes or living in vulnerable circumstances due to ill health,” she said.

A pension credit is for people on low incomes and unlocks a number of other benefits. It ensures that single people have an income of at least £218.15 a week, and that pensioner couples have at least £332.

For over a decade about a third of pensioners who are entitled have not claimed it. The result will be colder homes and more death.

In 2020/21, 14,502 people died because of cold homes—a huge change from 2,439 the year before. The number of excess deaths was 4,950 last year.

Gillian Cooper, the director of energy at Citizens Advice, said, “One in four say they could be forced to turn off their heating and hot water this winter.

“We’re particularly concerned about households with children and young people and those on lower incomes, who are most likely to struggle with their heating costs.”

And standing charges—a fixed daily amount that covers the costs of connecting to a supply—are staying the same. These are typically 60p a day for electricity and 31p a day for gas.

These charges are unfair because they make up a disproportionately large part of bills for low energy users.

Plus the regulator is adding £28 to everyone’s bill over the year to cover the cost of dealing with £3.1 billion of debt owed to suppliers.

No comments:

Post a Comment