WAIT, WHAT?!

Rapper Ye’s fans amazed after China’s censors let him perform there

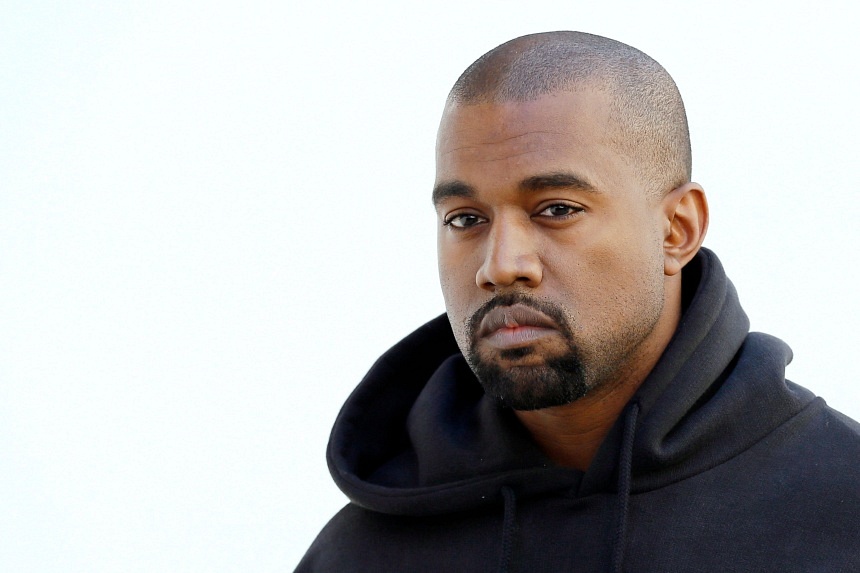

Ye, the rapper formerly known as Kanye West, will be performing in China on Sept 15. PHOTO: AFP

Sep 15, 2024

BEIJING – When the news broke that Ye, the rapper formerly known as Kanye West, would be performing in China on Sept 15, the elation of many of his fans was mixed with another emotion: confusion.

Why would the notoriously prickly Chinese government let in the notoriously provocative Ye? Why was the listening party, as Ye calls his shows, taking place not in Beijing or Shanghai, but in Hainan, an obscure island province?

Under a trending hashtag on social media site Weibo on the subject, one popular comment simply read “How?”, alongside an exploding-head emoji.

The answer may lie in China’s struggling economy. Since China reopened its borders after three years of coronavirus lockdowns, the government has been trying to stimulate consumer spending and promote tourism.

“Vigorously introducing new types of performances desired by young people, and concerts from international singers with super internet traffic, is the outline for future high-quality development,” the government of Haikou, the city hosting the listening party, posted on its website on Sept 12.

But it is unclear whether the appearance by Ye – who would be perhaps the highest-profile Western artist to perform in mainland China since the pandemic – is part of a broader loosening or an exception.

Even before the pandemic, the number of big-name foreign entertainers visiting China had been falling as the authorities tightened controls on speech. Acts such as Bon Jovi and Maroon 5 had shows abruptly cancelled, leading to speculation that band members’ expressions of support for causes like Tibetan independence were to blame. Justin Bieber was barred from China in 2017 over what the Beijing city government, without specifying, called “bad behaviour”.

Ye might have seemed like a no-go, too. The Chinese authorities declared war on hip-hop in 2018, with the state news media saying that artists who insulted women and promoted drug use “don’t deserve a stage”.

But in Ye’s case, objections to hip-hop may have been outweighed by the potential payoff – especially for Hainan.

For years, the Chinese government has sought to turn Hainan, an island roughly the size of Maryland or Belgium, into an international commercial hub. It offers visa-free entry and duty-free shopping, and has pledged to attract more world-class cultural events.

Dr Sheng Zou, a media scholar at Hong Kong Baptist University, said enforcement of censorship was capricious. “When it comes to Ye, I guess his celebrity status may outweigh his identity as a hip-hop artist.”

For Mr Ricardo Shi, 25, an employee of a tech company in Shenzhen, the chance to see Ye was worth spending US$700 (S$900) on plane tickets for a two-day trip to Haikou. “It’s been so long since he last came to China,” he said. (Ye performed in Beijing and Shanghai in 2008.) “It’s a rare opportunity to be there in person.”

Ye, who is touring to promote Vultures, his new album series with singer Ty Dolla Sign, has praised China. He told Forbes in 2020 that the country “changed my life”. He lived in the city of Nanjing as a fifth grader when his mother was teaching English there.

And issues that have led Western brands to cut off collaborations with Ye and alienated many American fans, like his anti-Semitic and homophobic comments, are of less concern to Chinese officials.

Still, no artist can escape political scrutiny altogether.

A photo circulating on Chinese social media showed officials gathered around a conference table, before a screen that read: “Haikou Municipal Bureau of Tourism, Culture, Radio, Television and Sports ‘Kanye West World Tour Audiovisual Concert’ Risk Assessment Meeting.”

Reached by telephone, an employee at the bureau could not confirm the photo’s authenticity but said that similar meetings were routine before large-scale events.

“These things, in my opinion, are a kind of test,” the employee, who gave her surname as Wang, said of the Ye event. “In the future, there will be more foreigners coming to Hainan for similar concerts. As long as they provide positive energy, we’ll do it.”

No one has announced what songs Ye will play. Set lists must be preapproved by censors.

A week before officials announced Ye’s Hainan stop, a listening party planned for Taiwan was abruptly cancelled. The Taiwan organisers cited “unforeseen circumstances”. It is unclear whether the cancellation was related to Ye’s show in China, which claims sovereignty over Taiwan.

A publicist who has worked with Ye on past listening parties did not respond to a request for comment.

Even after Ye passed the Chinese censors, some complained that he should not have. A string of submissions to Haikou’s public complaints website objected to his lyrics and personal behaviour, with one user declaring them “inconsistent with our country’s cultural and social values”.

Some Ye supporters suggested that those complaints were from disgruntled Taylor Swift fans. Swift, with whom Ye has a long and well-documented feud, has yet to announce any China dates for her Eras tour. (Several Shanghai government advisers recently called on the city to loosen its concert approval processes, citing performers like Swift, whom they said were like “walking GDP”, or gross domestic product.)

The anti-Ye comments have since disappeared from the government website.

Sep 15, 2024

BEIJING – When the news broke that Ye, the rapper formerly known as Kanye West, would be performing in China on Sept 15, the elation of many of his fans was mixed with another emotion: confusion.

Why would the notoriously prickly Chinese government let in the notoriously provocative Ye? Why was the listening party, as Ye calls his shows, taking place not in Beijing or Shanghai, but in Hainan, an obscure island province?

Under a trending hashtag on social media site Weibo on the subject, one popular comment simply read “How?”, alongside an exploding-head emoji.

The answer may lie in China’s struggling economy. Since China reopened its borders after three years of coronavirus lockdowns, the government has been trying to stimulate consumer spending and promote tourism.

“Vigorously introducing new types of performances desired by young people, and concerts from international singers with super internet traffic, is the outline for future high-quality development,” the government of Haikou, the city hosting the listening party, posted on its website on Sept 12.

But it is unclear whether the appearance by Ye – who would be perhaps the highest-profile Western artist to perform in mainland China since the pandemic – is part of a broader loosening or an exception.

Even before the pandemic, the number of big-name foreign entertainers visiting China had been falling as the authorities tightened controls on speech. Acts such as Bon Jovi and Maroon 5 had shows abruptly cancelled, leading to speculation that band members’ expressions of support for causes like Tibetan independence were to blame. Justin Bieber was barred from China in 2017 over what the Beijing city government, without specifying, called “bad behaviour”.

Ye might have seemed like a no-go, too. The Chinese authorities declared war on hip-hop in 2018, with the state news media saying that artists who insulted women and promoted drug use “don’t deserve a stage”.

But in Ye’s case, objections to hip-hop may have been outweighed by the potential payoff – especially for Hainan.

For years, the Chinese government has sought to turn Hainan, an island roughly the size of Maryland or Belgium, into an international commercial hub. It offers visa-free entry and duty-free shopping, and has pledged to attract more world-class cultural events.

Dr Sheng Zou, a media scholar at Hong Kong Baptist University, said enforcement of censorship was capricious. “When it comes to Ye, I guess his celebrity status may outweigh his identity as a hip-hop artist.”

For Mr Ricardo Shi, 25, an employee of a tech company in Shenzhen, the chance to see Ye was worth spending US$700 (S$900) on plane tickets for a two-day trip to Haikou. “It’s been so long since he last came to China,” he said. (Ye performed in Beijing and Shanghai in 2008.) “It’s a rare opportunity to be there in person.”

Ye, who is touring to promote Vultures, his new album series with singer Ty Dolla Sign, has praised China. He told Forbes in 2020 that the country “changed my life”. He lived in the city of Nanjing as a fifth grader when his mother was teaching English there.

And issues that have led Western brands to cut off collaborations with Ye and alienated many American fans, like his anti-Semitic and homophobic comments, are of less concern to Chinese officials.

Still, no artist can escape political scrutiny altogether.

A photo circulating on Chinese social media showed officials gathered around a conference table, before a screen that read: “Haikou Municipal Bureau of Tourism, Culture, Radio, Television and Sports ‘Kanye West World Tour Audiovisual Concert’ Risk Assessment Meeting.”

Reached by telephone, an employee at the bureau could not confirm the photo’s authenticity but said that similar meetings were routine before large-scale events.

“These things, in my opinion, are a kind of test,” the employee, who gave her surname as Wang, said of the Ye event. “In the future, there will be more foreigners coming to Hainan for similar concerts. As long as they provide positive energy, we’ll do it.”

No one has announced what songs Ye will play. Set lists must be preapproved by censors.

A week before officials announced Ye’s Hainan stop, a listening party planned for Taiwan was abruptly cancelled. The Taiwan organisers cited “unforeseen circumstances”. It is unclear whether the cancellation was related to Ye’s show in China, which claims sovereignty over Taiwan.

A publicist who has worked with Ye on past listening parties did not respond to a request for comment.

Even after Ye passed the Chinese censors, some complained that he should not have. A string of submissions to Haikou’s public complaints website objected to his lyrics and personal behaviour, with one user declaring them “inconsistent with our country’s cultural and social values”.

Some Ye supporters suggested that those complaints were from disgruntled Taylor Swift fans. Swift, with whom Ye has a long and well-documented feud, has yet to announce any China dates for her Eras tour. (Several Shanghai government advisers recently called on the city to loosen its concert approval processes, citing performers like Swift, whom they said were like “walking GDP”, or gross domestic product.)

The anti-Ye comments have since disappeared from the government website.

NYTIMES

Historians say increased censorship in China makes research hard

September 15, 2024

September 15, 2024

By Reuters

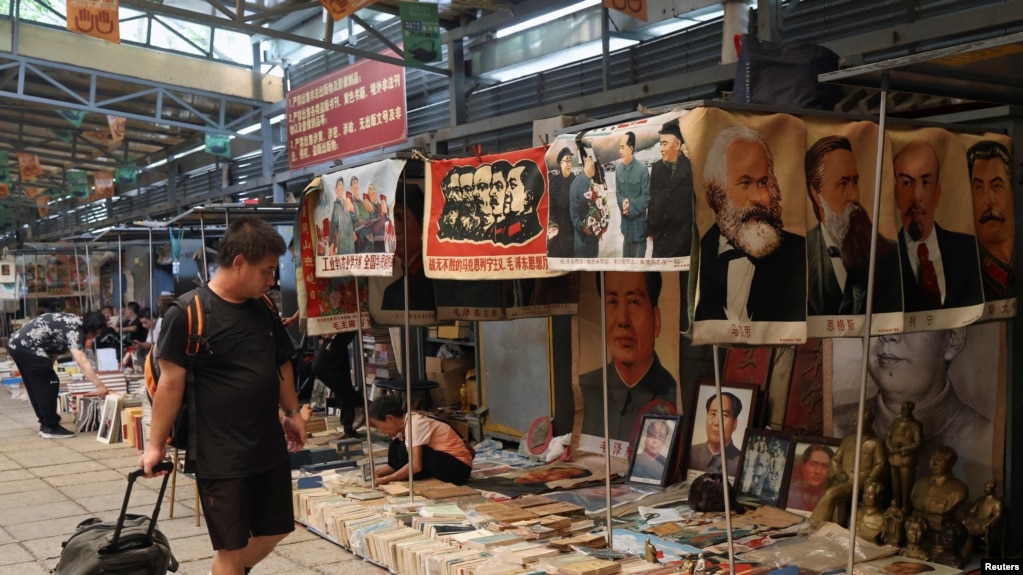

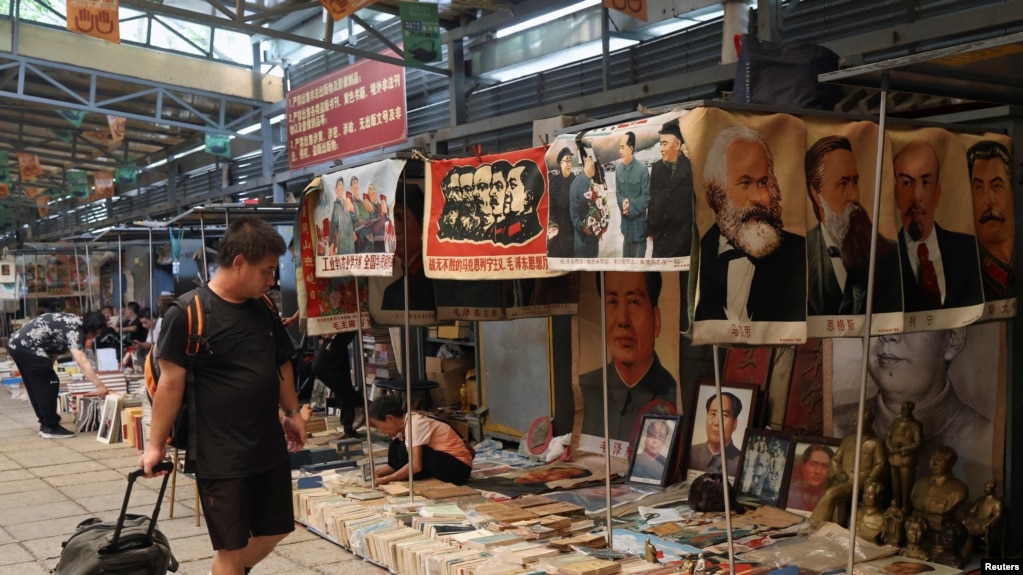

A man walks past a sign warning against the sale of illegal publications, underneath which secondhand books, images and statues of Chinese leaders are displayed for sale at the Panjiayuan antique market in Beijing, Aug. 3, 2024.

BEIJING —

At Beijing's largest antiques market, Panjiayuan, among the Mao statues, posters and second-hand books are prominent signs warning against the sale of publications that might have state secrets or "reactionary propaganda."

Some of the signs display a hotline number so that citizens can tip off authorities if they witness an illegal sale.

China's antique and flea markets were once a gold mine of documents for historians, but now the signs are emblematic of the chill that has descended on their ability to do research in the country.

On one hand, Beijing wants to increase academic exchange and President Xi Jinping last November invited 50,000 American students to China over the next five years -- a massive jump from about 800 currently.

How much steam that will gather is very much an open question. But scholars of modern Chinese history in particular -- arguably among the people most interested in China - fear that tightened censorship is extinguishing avenues for independent research into the country's past.

This is especially so for documents relating to the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution -- the most historically sensitive period for the Chinese Communist Party -- when Mao Zedong declared class war and plunged China into chaos and violence.

"I would say the period of going to flea markets and simply finding treasure troves is pretty much over," said Daniel Leese, a modern China historian at the University of Freiburg.

Trawling for documents "has basically gone out of favor because it has simply become too complex, difficult and dangerous," he said, adding that younger foreign scholars are increasingly relying on overseas collections.

The Chinese Communist Party has exerted control over all publications including books, the media and the internet since establishing the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, with the degree of censorship fluctuating over time.

But censorship has only intensified under President Xi Jinping, who came to power in 2012 and has blamed "historic nihilism" or versions of history that differ from the official accounts for causing the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In recent years, a raft of new national security and anti-espionage legislation has made scholars even more wary of citing unofficial Chinese materials.

Some scholars of modern Chinese history who have published studies that either challenged Chinese state narratives or are on sensitive topics say they have been denied visas to China.

James Millward, a historian at Georgetown University, said he had been visa-blocked on several occasions after contributing to the 2004 book Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland but has since received short-term visas a few times albeit after a lengthy process.

The political climate is also shaping how historians choose their research subjects. One historian based in the U.S. said he has chosen to work on non-controversial topics to maintain travel access to China. He declined to be identified due to the sensitivity of the issue.

BEIJING —

At Beijing's largest antiques market, Panjiayuan, among the Mao statues, posters and second-hand books are prominent signs warning against the sale of publications that might have state secrets or "reactionary propaganda."

Some of the signs display a hotline number so that citizens can tip off authorities if they witness an illegal sale.

China's antique and flea markets were once a gold mine of documents for historians, but now the signs are emblematic of the chill that has descended on their ability to do research in the country.

On one hand, Beijing wants to increase academic exchange and President Xi Jinping last November invited 50,000 American students to China over the next five years -- a massive jump from about 800 currently.

How much steam that will gather is very much an open question. But scholars of modern Chinese history in particular -- arguably among the people most interested in China - fear that tightened censorship is extinguishing avenues for independent research into the country's past.

This is especially so for documents relating to the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution -- the most historically sensitive period for the Chinese Communist Party -- when Mao Zedong declared class war and plunged China into chaos and violence.

"I would say the period of going to flea markets and simply finding treasure troves is pretty much over," said Daniel Leese, a modern China historian at the University of Freiburg.

Trawling for documents "has basically gone out of favor because it has simply become too complex, difficult and dangerous," he said, adding that younger foreign scholars are increasingly relying on overseas collections.

The Chinese Communist Party has exerted control over all publications including books, the media and the internet since establishing the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, with the degree of censorship fluctuating over time.

But censorship has only intensified under President Xi Jinping, who came to power in 2012 and has blamed "historic nihilism" or versions of history that differ from the official accounts for causing the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In recent years, a raft of new national security and anti-espionage legislation has made scholars even more wary of citing unofficial Chinese materials.

Some scholars of modern Chinese history who have published studies that either challenged Chinese state narratives or are on sensitive topics say they have been denied visas to China.

James Millward, a historian at Georgetown University, said he had been visa-blocked on several occasions after contributing to the 2004 book Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland but has since received short-term visas a few times albeit after a lengthy process.

The political climate is also shaping how historians choose their research subjects. One historian based in the U.S. said he has chosen to work on non-controversial topics to maintain travel access to China. He declined to be identified due to the sensitivity of the issue.

Busts and statues portraying late Chinese chairman Mao Zedong are seen at the Panjiayuan flea market in Beijing, May 19, 2019.

China's education ministry did not respond to a Reuters request for comment. The foreign ministry said it was unaware of relevant circumstances.

Documentary discoveries

Leese and other foreign historians say they previously found case files of persecuted intellectuals as well as secret Communist Party documents at Chinese flea and antique markets.

These were often donated by relatives of deceased officials or painstakingly rescued by booksellers from recycling centers near government offices disbanded during the mass state sector layoffs of the 1990s.

But the government has, since 2008, cracked down on flea markets and other sources of used books and documents. Buyers have been arrested, sellers have been fined and used book websites have been cleared of politically sensitive items, according to domestic media reports, collectors and four overseas researchers who spoke with Reuters.

In 2019, for example, a Japanese historian was detained for two months on spying charges after buying 1930s books on the Sino-Japanese War from a second-hand bookshop.

Two years later, a hobbyist accused of selling illegal publications from Hong Kong and Taiwan publishers on Kongfuzi, China's biggest website for used books, was fined 280,000 yuan ($39,000) for not having a business license, Chinese media reported.

And this year, two workers at a recycling center were punished for selling confidential military documents, state media said.

Buyers now cultivate personal relationships with merchants who sell through WeChat, said a Beijing-based collector interested in documents from the Cultural Revolution, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Historians also note that access to the vast majority of local government archives has been restricted since 2010 and their digitization has enabled censors to heavily redact them.

Foreign-based historians add that their counterparts in mainland China can only preserve materials for posterity in the current political climate. But not all are downbeat.

"Even under Xi, Chinese scholars continue to seek openings and enlarge the understanding and interpretation of PRC history," said Yi Lu, assistant history professor at Dartmouth College, who has worked extensively with Chinese university collections of 20th-century materials. "All is not lost."

China's education ministry did not respond to a Reuters request for comment. The foreign ministry said it was unaware of relevant circumstances.

Documentary discoveries

Leese and other foreign historians say they previously found case files of persecuted intellectuals as well as secret Communist Party documents at Chinese flea and antique markets.

These were often donated by relatives of deceased officials or painstakingly rescued by booksellers from recycling centers near government offices disbanded during the mass state sector layoffs of the 1990s.

But the government has, since 2008, cracked down on flea markets and other sources of used books and documents. Buyers have been arrested, sellers have been fined and used book websites have been cleared of politically sensitive items, according to domestic media reports, collectors and four overseas researchers who spoke with Reuters.

In 2019, for example, a Japanese historian was detained for two months on spying charges after buying 1930s books on the Sino-Japanese War from a second-hand bookshop.

Two years later, a hobbyist accused of selling illegal publications from Hong Kong and Taiwan publishers on Kongfuzi, China's biggest website for used books, was fined 280,000 yuan ($39,000) for not having a business license, Chinese media reported.

And this year, two workers at a recycling center were punished for selling confidential military documents, state media said.

Buyers now cultivate personal relationships with merchants who sell through WeChat, said a Beijing-based collector interested in documents from the Cultural Revolution, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Historians also note that access to the vast majority of local government archives has been restricted since 2010 and their digitization has enabled censors to heavily redact them.

Foreign-based historians add that their counterparts in mainland China can only preserve materials for posterity in the current political climate. But not all are downbeat.

"Even under Xi, Chinese scholars continue to seek openings and enlarge the understanding and interpretation of PRC history," said Yi Lu, assistant history professor at Dartmouth College, who has worked extensively with Chinese university collections of 20th-century materials. "All is not lost."

No comments:

Post a Comment