India faces its worst locust swarm in nearly 30 years

The pests have destroyed over 50,000 hectares of cropland, putting further strain on the food supply in India as authorities battle to contain the coronavirus.

On Tuesday, Indian authorities sent out drones and tractors to track desert locusts and spray them with insecticides, in one of the worst locust swarms seen by the country in nearly 30 years. With about 50,000 hectares of cropland destroyed by locusts, India is facing its worst food shortages since 1993.

"Eight to 10 swarms, each measuring around a square kilometer, are active in parts of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh," K.L. Gurjar, the deputy director of India's Locust Warning Organization, told news agency AFP. The locusts have also made their way to other states of India including Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh.

On Monday, a swarm of locusts infested the city of Jaipur in Rajasthan, after traveling into India from Pakistan. Gurjar warned that the locusts could move towards the capital city of Delhi if wind speed and direction was favorable.

More than half of the 33 districts in Rajasthan were affected by the locusts

Why a locust swarm is alarming

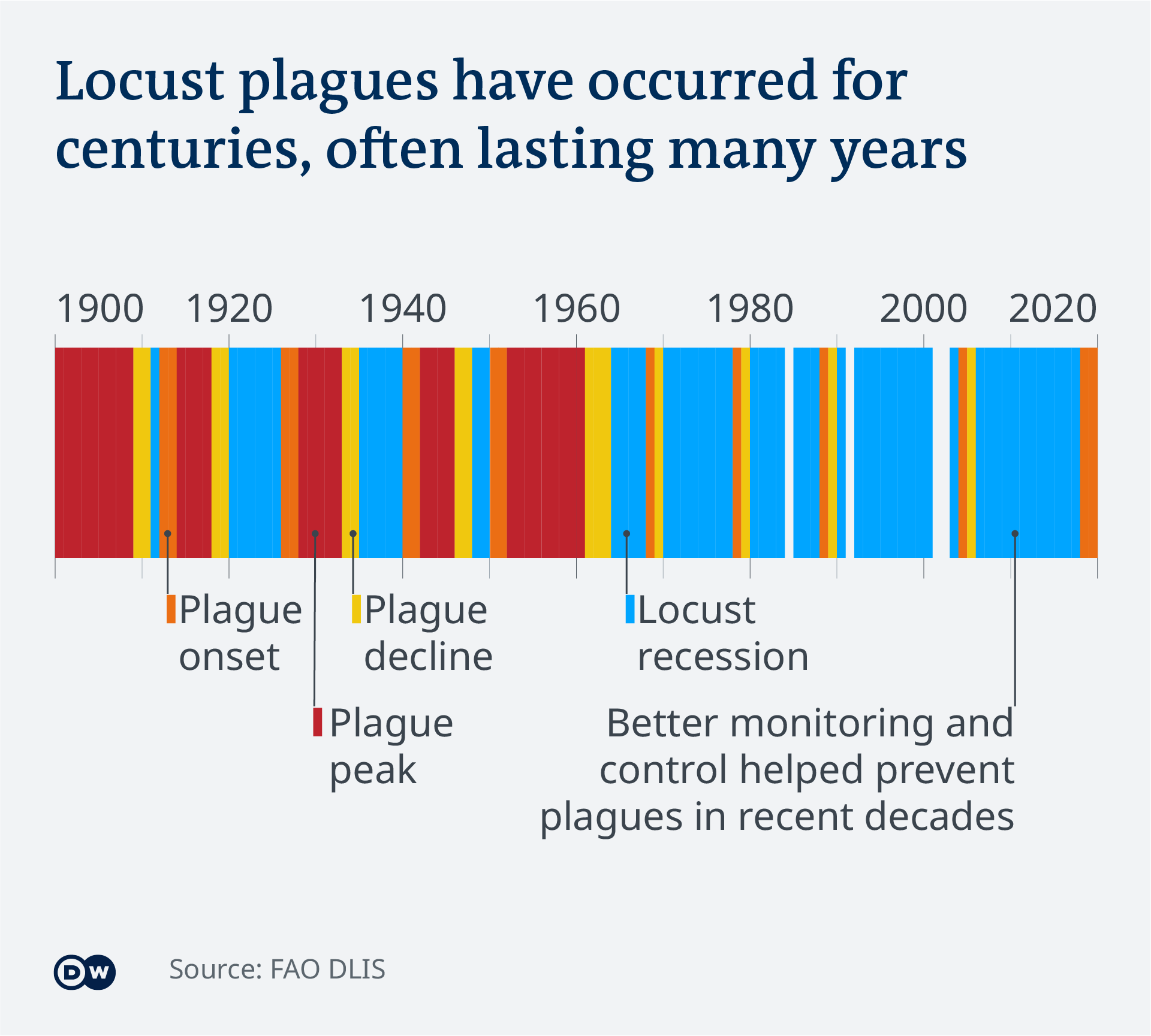

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) desert locusts typically attack the western part of India and some parts of the state of Gujarat from June to November. However, the Ministry of Agriculture's Locust Warning Organization spotted them in India as early as April this year.

A swarm of 40 million locusts can eat as much food as 35,000 humans, according to FAO estimates. The current swarm has destroyed seasonal crops in the states of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. This will lead to lower production than usual and a rise in prices of foodstuff.

An agrarian crisis and subsequent food inflation will severely impede India's response to the coronavirus pandemic. Thousands of migrant workers have died from hunger after India suddenly imposed a nationwide lockdown to contain the spread of the coronavirus, leaving workers penniless. An agrarian crisis because of a locust swarm will further hamper relief efforts of the government.

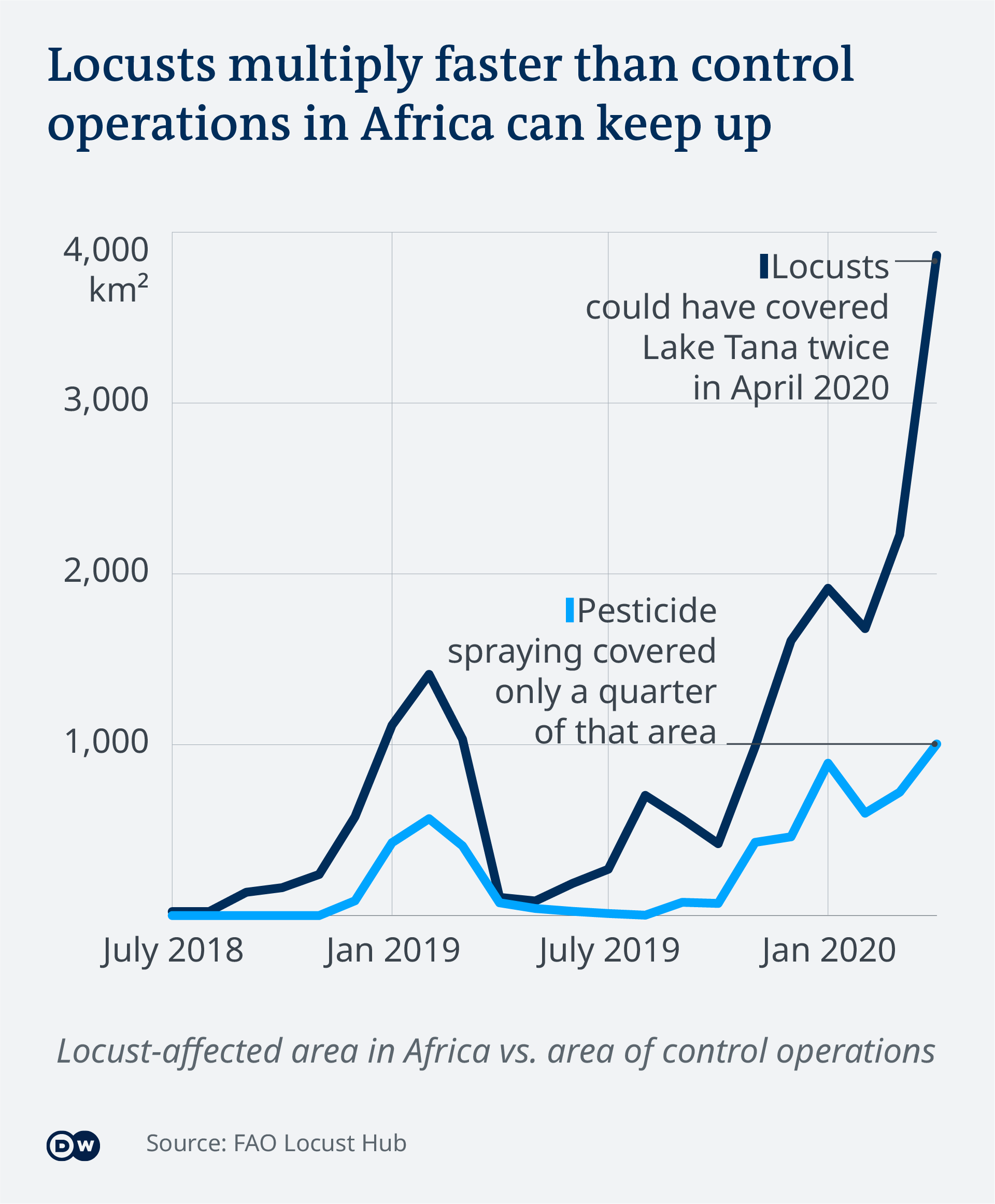

Heavy rains and cyclones in the Indian Ocean are being cited by experts as reasons for increased breeding of locusts this year. The attack is also spread over a wider geography in India. The FAO has warned that the locust infestation will increase next month, when locusts breeding in East Africa reach India.

Other parts of the world affected by locusts

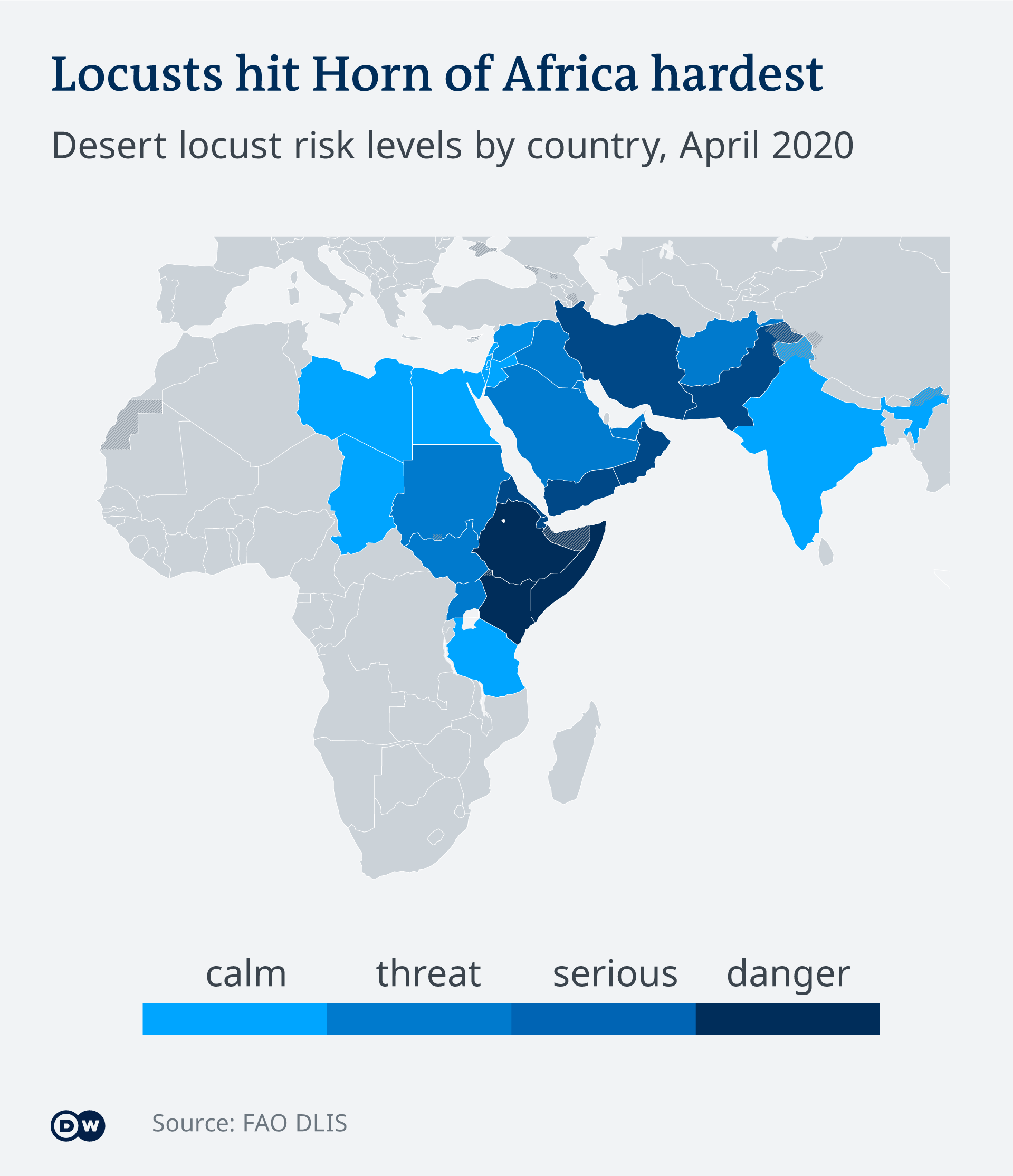

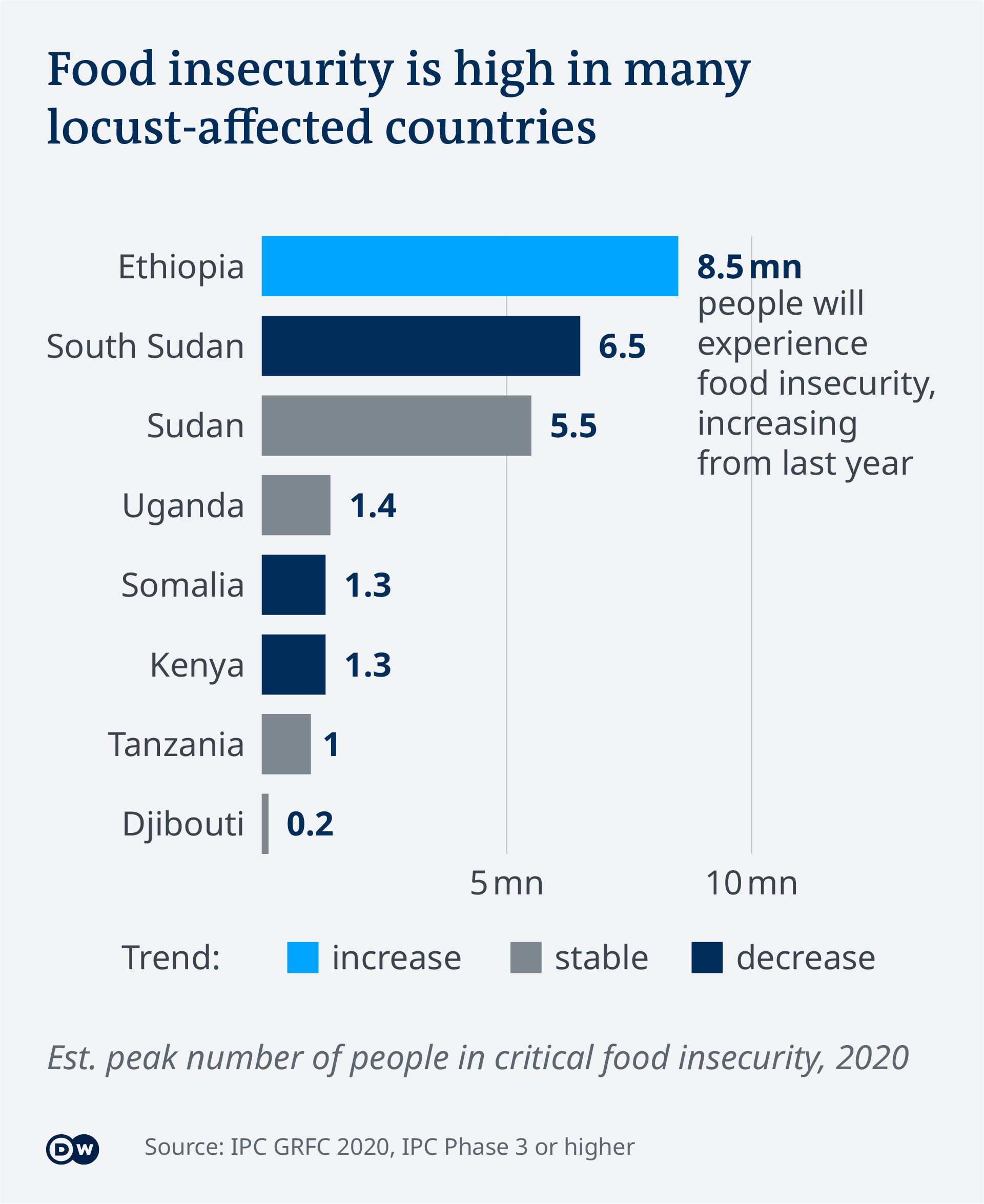

India isn't the only country attacked by a huge swarm of locusts this year. Pakistan,countries in East Africa, and Yemen have also faced the desert pests and their destruction. In February, Pakistan declared a national emergency because of locust attacks in the eastern part of the country. The pests damaged cotton, wheat, maize and other crops.

Earlier this month, the FAO said that it had made a headway in dealing with the locust invasion by saving 720,000 tons of cereal in 10 countries

Date 27.05.2020

Related Subjects India

Keywords India, locusts, crops, famine

Permalink https://p.dw.com/p/3coS

Historic swarm of locusts descends upon India, destroying cropsMay 27 (UPI) -- India is experiencing a historic swarm of locusts as the country also deals with the COVID-19 pandemic and sweltering heat.

Swarms of desert locusts have descended upon portions of the states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya, Pradesh, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, while alerts were issued in the capital city of Delhi warning the insects could soon arrive there.

India's Locust Warning Organization has said at least 10 swarms of up to 80 million locusts have made their way through India, destroying crops.

The organization said locust infestation is the worst the country has ever seen, coming before their usual migration from Pakistan between July and October and extending far beyond Rajasthan, where they have historically been centralized

Experts say that extreme heat in the nation, which has reached highs of 122 degrees, has contributed to the uncommonly large swarm.

"The outbreak started after warm waters in the western Indian Ocean in late 2019 fueled heavy amounts of rains over east Africa and the Arabian Peninsula," Dr. Roxy Mathew Koll, a senior scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, said. "These warm waters were caused by the phenomenon called the Indian Ocean Dipole -- with warmer than usual waters to its west and cooler waters to its east. Rising temperatures due to global warming amplified the dipole and made the western Indian Ocean particularly warm."

The swarms have destroyed about 123,500 acres of cropland in the Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh state.

States, including Jaipur, have deployed drones to spray locusts in order to clear the areas of locusts.

"It has successfully contained the movement of locusts in an open area and on the foothills where it was not possible for the usual tractors to make it reach. A detailed assessment of its impact is being studied by the field officers," said Om Prakash, commissioner of the Jaipur state agriculture department.

The drones are attached with spray tanks that can disperse chemicals for 10 minutes before being refilled by a handler.

"The biggest advantage of the drone is that it can fly above the flying zone of the locusts giving the flexibility to the officials to carry out combat operation while they are flying. Earlier, the operations were restricted to when they are resting n a tree or on a crop," Prakesh said

SEE

https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/05/india-wilts-under-heatwave-as.html

https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/05/data-analysis-how-east-africa-is.html

https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/05/covid-19-locusts-and-floods-east.html