ECOLOGY

Study shows how millions of bird sightings unlock precision conservation

Zoomable maps pinpoint where birds are declining most; some locales with positive trends

Cornell University

image:

American Robin

view moreCredit: Ian Davies; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

ITHACA, N.Y. —A groundbreaking study published today in Science reveals that North American bird populations are declining most severely in areas where they should be thriving.

Researchers from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology analyzed 36 million bird observations shared by birdwatchers to the Cornell Lab’s eBird program alongside multiple environmental variables derived from high-resolution satellite imagery for 495 bird species across North America from 2007 to 2021.

The team set out to develop reliable information about where birds are increasing or decreasing across North America, but the patterns they uncovered were startling.

Birds are declining most severely where they are most abundant—the very places where they should be thriving. Eighty-three percent of the species they examined are losing a larger percentage of their population where they are most abundant.

“We're not just seeing small shifts happening, we're documenting populations declining where they were once really abundant. Locations that once provided ideal habitat and climate for these species are no longer suitable. I think this is indicative of more major shifts happening for the nature that's around us,” said Alison Johnston, lead author and ecological statistician. Johnston initiated this study as a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and now she is a faculty member in the School of Mathematics and Statistics at the University of St. Andrews, UK.

This news follows on the heels of other recent research that documented widespread losses of birds in North America. The 2025 U. S. State of the Birds report showed bird declines in almost every biome in the nation, and a 2019 paper published in Science reported a cumulative population loss of nearly 3 billion birds in Canada and the U.S. since 1970. “The 2019 paper was telling us that we have an emergency, and now with this work we have the information needed to create an emergency response plan,” said Johnston.

This research published in Science features recent bird population trends at 27 km by 27 km scales, the smallest parcels of land ever attempted for an analysis across such a large geographic area.

“This is the first time we’ve had fine scale information on population changes across such broad spatial extents and across entire ranges of species. And that provides us a better lens to understand the changes that are happening with bird populations,” said Amanda Rodewald, faculty director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Previously national and continental monitoring programs could estimate population trends only across entire ranges, regions, or states/provinces, but with advances in machine learning and the accumulation of vast amounts of data from participatory scientists, researchers can look at how well species are doing in areas about the size of New York City. Some species appear to be doing well across their range or within a region, but are fairing very poorly in specific locations within those regions.

“The thing that is super interesting is that for almost all species we found areas of population increases and decreases,” said Johnston. “This spatial variation in population trends has been previously invisible when looking at broader regional summaries.”

Areas where populations are increasing are the bright spots, said Johnston: “Areas where species are increasing where they're at low abundance may be places where conservation has been successful and populations are recovering, or they may point to locations where there may be potential for recovery.”

Key findings from the study include:

|

Knowing exactly where on the landscape declines are happening helps scientists start to identify the drivers of those declines and how to respond to them.

“It’s this kind of small-scale information across broad geographies that has been lacking and it’s exactly what we need to make smart conservation decisions. These data products give us a new lens to detect and diagnose population declines and to respond to them in a way that's strategic, precise, and flexible. That's a game changer for conservation,” said Rodewald.

The study's detailed mapping of population changes will help conservation organizations and policymakers better target their efforts to protect declining bird species, which according to the authors is sorely needed to help reverse the declining population trends.

The research also reveals the power of participatory science data. “Knowledge is power. Because of the volunteers that engage in programs like eBird, because of their enthusiasm and engagement, and generosity of time, we now know more about bird populations and more about the environment than we ever have before,” said Rodewald.

“Without the massive amount of data available from eBird, we would not have been able to complete this study,” said Daniel Fink, a senior research associate and statistician at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. But, Fink shared, with all of that information comes many analytical challenges. “We employed causal machine learning models and novel statistical methodologies that allowed us to estimate changes in populations with high spatial resolution while also accounting for biases that come from changes in how and where people go birding,” Fink said. To ensure the reliability of the data the team ran over half a million simulations, stacking up more than 6 million hours of computing, which would take about 85 years to run on a standard laptop computer.

This research was made possible by funding from a number of different sources over several years: The Leon Levy Foundation, The Wolf Creek Foundation, and National Science ABI sustaining: DBI-1939187. Computing support was provided by grants from the National Science Foundation through CNS-1059284 and CCF-1522054. This work used Bridges2 at Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center and Anvil (Song et al. 2022) at the Rosen Center for Advanced Computing at Purdue University through allocation DEB200010 (DF, TA, SL, OR) from the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, which is supported by NSF grants #2138259, #2138286, #2138307, #2137603, and #2138296.

####

Reference: Johnston, A., A. D. Rodewald, M. Strimas-Mackey, T. Auer, W. M. Hochachka, A. N. Stillman, C. L. Davis, V. Ruiz-Gutierrez, A. M. Dokter, E. T. Miller, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, L. Oldham Jaromczyk, C. Crowley, C. L. Wood, and D. Fink. (2025). North American bird declines are greatest where species are most abundant. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.adn4381

Editors: Download images. The use of this material is protected by copyright. Use is permitted only within stories about the content of this release. Redistribution or any other use is prohibited without express written permission of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology or the copyright owner.

Note: More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak/

Population trends of American Robin. Red dots indicate population decreases, blue dots indicate population increases, and the size of the dots indicates relative abundance. The darker the red and the larger the dot indicate strong declines in places where American Robins are most abundant.

Credit

Courtesy of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Williamson's Sapsucker

Credit

Steve Wickliffe; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Great Blue Heron

Credit

Daniel Grossi; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Journal

Science

Method of Research

Data/statistical analysis

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

North American bird declines are greatest where species are most abundant

Article Publication Date

1-May-2025

North American birds are disappearing fastest where they are most abundant

Summary author: Walter Beckwith

North American bird populations are shrinking most rapidly in the very areas where they are still most abundant, according to a new study leveraging citizen science data for nearly 500 bird species. The findings reveal both urgent threats and potential opportunities for targeted conservation and recovery. Bird populations are experiencing steep declines globally, with North America losing more than 25% of all breeding birds since 1970. While long-term monitoring has revealed these troubling trends, effective conservation requires knowing where populations are declining most. However, this goal has been limited by the lack of fine-scale, spatially comprehensive data on bird population trends, making it difficult to prioritize efforts or detect localized patterns of decline and recovery. To address this need, Alison Johnston and colleagues compiled citizen science data from over 36 million eBird checklists, spanning 2007 to 2021, to generate fine-scale population trends for 495 bird species across North America, Central America, and the Caribbean. By analyzing changes in bird sightings at a high spatial resolution, the authors were able to separate actual shifts in bird populations from differences in observer behavior. Their approach involved using a specialized machine learning model, which enabled the detection of nuanced population changes with high statistical reliability.

The analysis revealed a complex patchwork of local population dynamics; although overall trends show that 75% of bird species are declining across their ranges – and 65% significantly so – nearly every species (97%) is experiencing both gains and losses depending on location within their ranges. Notably, Johnston et al. found that bird populations are declining fastest in the very places where they remain most abundant. This pattern – observed in 83% of species – suggests that even the strongholds of bird populations are no longer safe. The declines are especially severe in birds that breed in grasslands and drylands, and declines are more closely tied to local abundance than geographic position within a species’ range, the findings suggest; this points to ecological stress – climate change and habitat loss – as the primary driver of decline. Habitats that support abundant populations may be more vulnerable to these pressures, while species in marginal habitats may have greater resilience. Yet, despite widespread declines, the study revealed pockets of stability, such as in the Appalachians and western mountains, which may offer refuge or point to conditions that could facilitate recovery.

For reporters interested in trends, a 2019 Research Article in Science reported that North America had lost nearly three billion birds since 1970.

Journal

Science

Article Title

North American bird declines are greatest where species are most abundant

Article Publication Date

1-May-2025

AI system targets tree pollen behind allergies

UTA researchers help develop a tool to aid allergy sufferers, farmers and city planners

image:

Pollen analysis is a powerful method for reconstructing historical ecosystems. Preserved pollen grains in lakebeds and peat bogs offer detailed records of past plant communities. Since plant distribution is tightly linked to environmental factors such as temperature, rainfall and humidity, identifying the types of pollen present in different layers of sediment can reveal how ecosystems have responded to natural climate fluctuations over time and how they might react in the future.

view moreCredit: UTA

Imagine trying to tell identical twins apart just by looking at their fingerprints. That’s how challenging it can be for scientists to distinguish the tiny powdery pollen grains produced by fir, spruce and pine trees.

But a new artificial intelligence system developed by researchers at The University of Texas at Arlington, the University of Nevada and Virginia Tech is making that task a lot easier—and potentially bringing big relief to allergy sufferers.

“With more detailed data on which tree species are most allergenic and when they release pollen, urban planners can make smarter decisions about what to plant and where,” said Behnaz Balmaki, assistant professor of research in biology at UT Arlington and coauthor of a new study published in the journal Frontiers in Big Data with Masoud Rostami from the Division of Data Science at UTA. “This is especially important in high-traffic areas like schools, hospitals, parks and neighborhoods. Health services could also use this information to better time allergy alerts, public health messaging and treatment recommendations during peak pollen seasons.”

Pollen analysis is a powerful method for reconstructing historical ecosystems. Preserved pollen grains in lakebeds and peat bogs offer detailed records of past plant communities. Since plant distribution is tightly linked to environmental factors such as temperature, rainfall and humidity, identifying the types of pollen present in different layers of sediment can reveal how ecosystems have responded to natural climate fluctuations over time and how they might react in the future.

“Even with high-resolution microscopes, the differences between pollens are very subtle,” Dr. Balmaki said. “Our study shows deep-learning tools can significantly enhance the speed and accuracy of pollen classification. That opens the door to large-scale environmental monitoring and more detailed reconstructions of ecological change. It also holds promise for improving allergen tracking by identifying exactly which species are releasing pollen and when.”

Related: The impact of climate change on food production

Balmaki adds that the research could also benefit agriculture.

“Pollen is a strong indicator of ecosystem health,” she said. “Shifts in pollen composition can signal changes in vegetation, moisture levels and even past fire activity. Farmers could use this information to track long-term environmental trends that affect crop viability, soil conditions or regional climate patterns. It’s also useful for wildlife and pollinator conservation. Many animals, including insects like bees and butterflies, rely on specific plants for food and habitat. By identifying which plant species are present or declining in an area, we can better understand how these changes impact the entire food web and take steps to protect critical relationships between plants and pollinators.”

Related: Harmful microplastics infiltrating drinking water

For this study, the team examined historical samples of fir, spruce and pine trees preserved by the University of Nevada’s Museum of National History. They tested those samples using nine different AI models, demonstrating the technology’s strong potential to identify pollen with impressive speed and accuracy.

“This shows that deep learning can successfully support and even exceed traditional identification methods in both speed and accuracy,” Balmaki said. “But it also confirms how essential human expertise still is. You need well-prepared samples and a strong understanding of ecological context. This isn’t just about machines—it’s a collaboration between technology and science.”

For future projects, Balmaki and her collaborators plan to expand their research to include a wider range of plant species. Their goal is to develop a comprehensive pollen identification system that can be applied across different regions of the United States to better understand how plant communities may shift in response to extreme weather events.

About The University of Texas at Arlington (UTA)

Celebrating its 130th anniversary in 2025, The University of Texas at Arlington is a growing public research university in the heart of the thriving Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. With a student body of more than 41,000, UTA is the second-largest institution in the University of Texas System, offering more than 180 undergraduate and graduate degree programs. Recognized as a Carnegie R-1 university, UTA stands among the nation’s top 5% of institutions for research activity. UTA and its 280,000 alumni generate an annual economic impact of $28.8 billion for the state. The University has received the Innovation and Economic Prosperity designation from the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities and has earned recognition for its focus on student access and success, considered key drivers to economic growth and social progress for North Texas and beyond.

“Pollen is a strong indicator of ecosystem health,” said Behnaz Balmaki, assistant professor of research in biology at UT Arlington. “Shifts in pollen composition can signal changes in vegetation, moisture levels and even past fire activity. Farmers could use this information to track long-term environmental trends that affect crop viability, soil conditions or regional climate patterns. It’s also useful for wildlife and pollinator conservation. Many animals, including insects like bees and butterflies, rely on specific plants for food and habitat. By identifying which plant species are present or declining in an area, we can better understand how these changes impact the entire food web and take steps to protect critical relationships between plants and pollinators.”

Credit

UTA

Journal

Frontiers in Big Data

Method of Research

Data/statistical analysis

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Deep learning for accurate classification of conifer pollen grains: enhancing species identification in palynology

Catron County’s Latest Anti-Wolf Theatrics Should be Roundly Booed

Mexican Wolf. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

Since before New Mexico was a state, Catron County has been fighting against federal authority, resisting commonsense efforts to rein in logging- and grazing-based destruction, and insisting instead on self-governance and ecological ruin. The county encompasses nearly 7,000 square miles of forests and grasslands, rivers, archeological sites, unique geological formations and designated Wilderness. It’s largely unpopulated with just 3600 people, but they have loomed large on the western landscape for their anti-federal, county-supremacy positions and hostility to environmental regulation.

The latest example of this form of “governance” is the Catron County Commission passing a resolution asking the New Mexico governor to declare a state of emergency over the “natural disaster” of Mexican gray wolf reintroduction. A few squeaky-wheel ranchers have somehow convinced local residents to ignore the crushing poverty, high unemployment rate, the higher-than-average number of suicides, expensive housing, and percentage of high-school drop-outs, and instead blame their problems on the Big, Bad Wolf.

Mexican wolves are actually not that big – maxing out around 80 lbs for males – or bad at all: there is no case of a Mexican wolf ever harming a human. Not once, ever, in recorded history. Most of the approximately 280 wolves in the wild distributed between Arizona and New Mexico don’t even prey on livestock, but you wouldn’t know that from the horror stories shared on social media and at the April 3, 2025 commission meeting. Depredation rates have been going down overall, coinciding with an uptick in proactive coexistence measures like range-riding and the reformed standards being used to determine wolf involvement in livestock deaths, but being proactive and responsible for their livestock isn’t the solution these folks are after. They want the species defunded, delisted, and subject to “management” directed by the business end of a rifle.

Catron County has opposed Mexican wolf recovery from the outset. When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed its first Recovery Plan for the Mexican wolf in 1982, the county opposed it based on concerns it would decimate the livestock industry. In 1992 the County Commission passed ordinance 002-92, forbidding the release of Mexican wolves anywhere in the county; this was superseded by Ordinance 002-2002 ten years later, specifying fines of hundreds of dollars and up to three months’ jail time for anyone (presumably including federal and state officials) releasing predators within the county. By 2007 the county was building bus-stop cages to “protect” schoolchildren from Mexican wolves and passing ordinances to allow itself to trap or kill this federally-protected species, the Endangered Species Act notwithstanding. (This was overturned in court.)

It isn’t just the wolves, but a generalized hostility to the role of the federal and state government in regulating regional activities. Catron County’s 1992 land-use plan’s introduction says: “Federal and state agents threaten the life, liberty, and happiness of the people of Catron County. They present a clear and present danger to the land and livelihood of every man, woman, and child. A state of emergency prevails that calls for devotion and sacrifice.” The plan was revised in 2007 and updated to say, “Maintaining the custom and culture of the County is critical for community and economic stability. This stability is highly dependent on the right of Catron County citizens to pursue and protect their way of life and economic structures from outside forces such as federal and state regulations.” In 1994, the county commission passed an ordinance urging every county resident to own a gun, and County Commissioner Carl Livingston was quoted as saying, “We want the Forest Service to know we’re prepared, even though violence would be a last resort.”

The April 2, 2025 resolution accuses the government of lying about the extent of wolf predation on livestock, and the reintroduction project of threatening the State and Country’s food supply “and thus our national security.” Neither of these things are true: Mexican wolves mostly eat elk, and Americans mostly eat beef raised in places other than the arid public lands of the west. But the facts haven’t stopped the fear-mongering, and the public testimony of the anti-wolf crowd hasn’t changed much since 2007, despite the reality that no kids have been harmed by wolves, the livestock industry hasn’t collapsed, and the bus shelters sit like unused props in a state of disrepair.

Catron County’s acting is as transparent as it ever was, but the difference now is they might have a friendly ear in the Trump Administration. From Brian Nesvik at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to Karen Budd-Falen at the Department of Interior (who helped draft Catron County’s 1992 land use plan), to Donald Trump Jr., the radical views of anti-wolf ranchers are reaching high places. For this brand of political theater, Catron County may have finally found its audience.

Mexican Wolf. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

Rational Analysis is Required Before Cutting and Burning Dry Forests

April 30, 2025

Graphic: The Forest Advocate

Fuels reduction treatments are the Forest Service’s primary strategy for reducing high severity fire and increasing “resilience” in dry forests. These treatments typically involve cutting large amounts of trees and understory from forests, followed by repeated prescribed burns. But do the benefits of such treatments outweigh the substantial ecological and social risks and costs? This question should be comprehensively considered in a cost/benefit analysis for each proposed vegetation reduction project. Conservation strategies should be developed that ensure forest restoration projects are a net benefit.

The Forest Service claims that it is not required to compare the ecological and social costs and benefits of its large-scale cutting and burning project proposals under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Whether this contention is legally defensible or not, failing to weigh the benefits of large-scale fuels treatments against the risks and costs is an egregious violation of the agency’s responsibility to the public. The costs of potential ecosystem degradation and escaped controlled burns require careful consideration. As the climate becomes warmer and drier, it is increasingly difficult to design dry forest vegetation treatment plans so that they provide net benefits. NEPA requires that the public be informed about the potential consequences of projects, and a cost/benefit analysis is key to understanding the relative importance of consequences.

Fire — including high-severity fire — is a natural and important aspect of forest ecology. Under the right conditions, fire can promote biodiversity and ecosystem renewal. However, in recent decades, acres burned at high severity have been increasing, although there is still a historical fire deficit. Climate transition has made conifer regeneration after high-severity fire much less certain: it is often delayed, and sometimes appears to fail altogether, resulting in some forested landscapes type-converting into shrublands. Fuels reduction treatments can reduce the number of acres that burn at high severity for a period of time, but this benefit must be weighed against serious tradeoffs.

The agency claims that vegetation management treatments improve ecosystem resilience, but their treatments often appear to degrade ecosystems. Cutting and burning treatments frequently cause substantial ecological damage, such as soil erosion and compaction, damage to the trees that are left standing, bark beetle infestation, tree blowdown (because removing trees from a grouping decreases structural support for the remaining trees), sediment flow into waterways, and disruption of wildlife habitat. Cut areas are subsequently treated with prescribed fire at overly-frequent intervals. The natural understory tends to not return, and uncharacteristic understory often develops, including invasive species. Or little understory grows back at all, except for some grasses. The remaining landscape often becomes overly open, dried out, and ecologically stunted and dysfunctional.

Trees are already dying from drought stress and other impacts of climate change, which in many cases may amount to substantial vegetation reduction. Also, when considering how many fewer trees may burn during a high severity fire within treated areas, that estimate should be counterbalanced by the number of trees cut and burned during treatments. Often, more trees are destroyed by fuels reduction treatments than by wildfires.

Current fire ecology research indicates that the number of fuels treatments that have been encountered by a wildfire have been fairly low, less than one percent per year, although encounters are increasing due to climate change. This means that most vegetation reduction treatments will provide no benefit in terms of fire mitigation. Fuels reduction treatments have been shown to be of decreasing benefit during the very high intensity fires that burn during increasingly hot, dry and windy weather. Additionally, very open treated forests tend to be drier, and in some cases more flammable than forests with more closed canopies.

Whether forests should receive fuels reduction treatments, and what particular treatments should consist of, should be thoroughly and genuinely considered at the project level within environmental impact statements (EIS), which are the most comprehensive level of NEPA analysis. The goal of any forest treatment should be long-term forest restoration, while avoiding forest degradation. It’s an increasingly complex undertaking to determine which interventions will support forest restoration and which will result in forest degradation, and any attempt to find a “sweet spot” that provides a net benefit requires nuanced site-specific analysis.

Environmental impact statements consider a range of alternative actions, while less detailed environmental assessments typically include just an Action and No Action alternative. However, rarely, if ever, does the Forest Service complete a cost/benefit analysis of the alternatives, which should be part of any EIS. Although the agency must disclose potential environmental and social consequences of proposed actions, it is not required to select the alternative with the greatest net benefit or the fewest adverse impacts. Adverse impacts that are “necessary” to accomplish a project’s “purpose and need” are considered by the agency to be acceptable. A project’s purpose and need is generally based on a number of assumptions, some of which are often controversial, highly uncertain, or unproven.

In order to rationally compare costs and benefits of alternatives, it is necessary to base analysis on valid assumptions. Often, the Forest Service uses models that do not reflect current or future conditions and rely on best or worst case scenarios, resulting in analysis that is fundamentally flawed. An example of this is the assumptions that underlie the air quality section of the Santa Fe Mountains Project environmental assessment. In the Santa Fe area, prescribed burn smoke is a major issue because it seriously impacts vulnerable residents’ health. In order to analyze the air quality impacts, the Forest Service based their analysis on two assumptions:

– Not implementing the proposed project would result in the project area burning in its entirety – that is, two discontinuous sections spanning 18 miles.

– Implementing the proposed project would result in no wildfires at all occurring over a 10-year or more period.

These types of clearly extreme and unrealistic baseline assumptions undermine any meaningful analysis. Such a skewed approach can support predetermined outcomes … and it usually does. The resulting analysis can be considered largely irrelevant – garbage in, garbage out. Responsible and legitimate analysis must be based on meaningful and real-world assumptions.

A meaningful comparison of costs and benefits of vegetation treatments also requires appropriate reference conditions. Reference conditions help define and inform what condition ecosystems should be restored to, after ecosystems have been damaged, degraded, or destroyed. The Forest Service continues to rely on historical reference conditions to determine the desired condition for projects post-treatment. But due to the rapidly changing climate, historical reference conditions are now largely obsolete for forest restoration project design and analysis. In order to truly restore forests, the agency must utilize current reference conditions that represent areas with high ecological integrity and that have the least amount of impacts from grazing, mining, logging and other fuels reduction projects, road construction, and invasive species, etc. Current reference conditions are virtually never considered by the agency, so little meaningful basis is provided for a cost/benefit analysis of potential project effects.

Without a comprehensive cost/benefit analysis, fuel reduction projects are essentially a shot in the dark and may result in disasters. The 342,000 acre Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, which was ignited in the Santa Fe National Forest in 2022 due to two separate escaped Forest Service prescribed burns, illustrates the need for balancing risks with benefits when designing and analyzing fuels treatment projects. The adverse consequences of these fires, including burning out entire communities and thousands of acres of forest in which conifers may or may not substantially regenerate, far outweigh any possible benefits that the fuel reduction treatments might have provided. The landscape was too dry for broadcast prescribed burns to have been implemented safely enough during the spring windy season. Fire can escape from smoldering slash piles when the snow has melted off of the ground, especially in very dry forests. Overly cut areas open up the tree canopy so much that vegetation dries out and becomes more flammable. Trees that have blown over due to overly aggressive thinning can create a fire hazard. These concerns should have been weighed against the potential benefits of the treatments in the project analysis.

By doing so, genuine mitigations could have been incorporated into the project plan, which may have greatly improved the outcome of the project. Appropriate mitigations could have included limiting burning to only the safest burn windows, which means refraining from burning during the spring when high winds are abundant. Also, refraining from overly opening up the forest canopy during tree cutting operations in order to retain moisture in the soils and vegetation, and greatly reducing the number of piles of thinning debris by implementing only very limited and strategic thinning.

In recent years, the Forest Service has been generally unwilling to prepare environmental impact statements for vegetation reduction projects. And the Trump administration is now in progress of rapidly and radically rolling back NEPA analysis and protections. Their impetus is to rush into cutting and prescribed burns as quickly as possible, with little environmental review, and increasingly under emergency authority. Such truncated review prohibits reasonable cost/benefit analysis and will likely bring about more disasters to our forests and communities. Recently the US House of Representatives passed the “Fix Our Forests Act,” which supports more logging of our forests, while further rolling back environmental analysis and safeguards for logging and other fuel reduction projects. The Act is now awaiting a vote in the Senate. The public still has the opportunity to let Senators know that the Fix Our Forests Act will not “fix” forests, but instead will degrade our forests. It will take immense pressure from the public to require responsible analysis, but it is absolutely necessary in order to maintain ecologically functional forests into the future.

It is incumbent upon forest managers and the conservation community to develop a new holistic management paradigm for dry forests in a warming and drying climate – an approach that strongly focuses on strategies that increase moisture retention in forests, instead of overly opening up tree canopy by aggressive cutting and burning. Vegetation treatment timing and soil and vegetation moisture must be carefully considered. Under certain conditions, a treatment may be a net benefit; under different conditions, the adverse impacts may substantially outweigh the benefits of the same treatment. Given the high potential for adverse impacts, careful analysis may support only limited, light-handed thinning that preserves substantial tree canopy and natural understory.

The primary focus of forest restoration should be to support the retention of water in ecosystems by very conservatively utilizing already known approaches – and by developing new conservation approaches suitable for dry forests undergoing climate transition. Approaches can include earthworks to allow water to infiltrate into soils, promoting beaver habitation in order to retain water, decommissioning unnecessary forest roads that cause water run-off, removing cows from forest lands, and restoring soil mycorrhizal fungi which hold soil moisture.

If there is a genuine desire to protect and restore forests, then there should be an effort to fully and deeply consider and weigh the short-term and long-term effects of all forest interventions, with an attitude of learning, a deep holistic understanding of forest ecology, and a concern for local communities. During the upcoming storm of NEPA rollbacks and ensuing forest degradation, it is more necessary than ever to actively support responsible and reasonable project analysis.

Forest apparently type-converting as a result of vegetation reduction treatments. Such a result was not realistically considered in a cost/benefit analysis — La Cueva fuel break, Santa Fe National Forest Photo: Sarah Hyden

How the United States Is Failing Elephants—and What You Can Do

Photograph Source: Richard Giles – CC BY-SA 2.0

After Ringling Bros. ended its 145-year-long tradition of forcing elephants to perform in 2016, many assumed that the protracted era of American elephant abuse was finally over. Unfortunately, that isn’t true yet.

To be sure, there has been tremendous progress. Localities across the country, followed by some states, have banned bullhooks—the fireplace-poker-like devices with a sharp point on the end that are deployed on the most sensitive parts of elephants’ bodies to force them into compliance. Without these weapons, circuses insist they can’t use elephants, massive animals who can easily kill a person, on purpose or by accident, with a single trunk swipe or foot stomp.

After being trained to perform under the constant threat of punishment with a bullhook—and taught that if they don’t perform as directed, they will face a violent “tune-up” with a bullhook while chained down—the mere sight of a bullhook can instill enough fear to keep these majestic animals compliant. At least, most of the time.

Ringling Bros. Shifts From Elephant Acts

Unable to use elephants in jurisdictions that adopted bullhook bans, Ringling Bros. began leaving elephants chained in boxcars at specific stops along its routes. Indeed, the circus cited the increasing patchwork of local laws when it announced in 2015 that it would finally bow to long-standing public pressure and stop using elephants.

Today, Ringling Bros. features only willing human performers. Other circuses followed suit. But not all of them. Numerous circuses continue to chain elephants up and haul them around the country for a few brief moments of demeaning entertainment. Often, these animals are supplied by Carson & Barnes.

Elephants have repeatedly escaped from this notorious outfit, including twice in 2024. Loose elephants pose serious public safety threats, and the animals themselves are often injured, sometimes even killed. Carson & Barnes’ head trainer was caught on video attacking, electroshocking, yelling, and swearing at elephants while the animals cried out. Yet, numerous circuses continue to lease animal acts from Carson & Barnes.

Challenges Elephants Face in Zoos and Captivity

And it’s not just circuses. Even the best-intentioned zoos can’t provide the vast acreage these wide-ranging animals need. Elephants evolved to traverse many miles every day. Unable to move in any meaningful way and often kept on hard surfaces, captive elephants frequently suffer from painful arthritis and foot disease. Indeed, these are the leading reasons captive elephants are euthanized. Some zoos, such as the Bronx Zoo, even continue to hold these highly social animals in solitary confinement.

In 2024, the Oakland Zoo, whose six-acre elephant enclosure was one of the largest in the U.S. yet still comprised less than one percent of an elephant’s home range, made the compassionate decision to send its last surviving elephant to the Elephant Sanctuary. This marked the end of three-quarters of a century of keeping elephants, but not the end of the zoo’s work to help elephants in the wild.

CEO Nik Dehejia explained, “Oakland Zoo’s ‘elephant program of the future’ requires much more than our habitat and facilities can provide today for this species to thrive in human care.” Two decades prior, the Detroit Zoo made a similar decision, sending elephants Winkie and Wanda to The Elephant Sanctuary in recognition of their complex physical and psychological needs.

But Oakland and Detroit are the exceptions. Many more zoos continue to hold and breed elephants. In 2017, a cohort of American zoos even imported 18 wild-captured elephants.

Given the extensive knowledge of how complex these animals’ needs are, how extraordinarily social and remarkably intelligent they are, how is it that hundreds of elephants are still confined across the U.S.? Why haven’t we banned these outdated exhibits? What legal protections do these animals have?

Insufficient Standards for Elephants on a Federal Level

The primary law governing the treatment of captive elephants in the U.S. is the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA). Congress intended this law to ensure the humane care and treatment of animals like elephants who are used for exhibition. However, the AWA’s standards are truly minimal. They lack elephant-specific requirements.

Instead, elephants are governed by the same generic standards that regulate most animals, from bats to bears to tigers to zebras. For example, these standards don’t set forth specific space requirements. Instead, they vaguelyrequire “sufficient space to allow each animal to make normal postural and social adjustments with adequate freedom of movement,”—which inspectors and regulated entities alike have struggled to understand, let alone enforce. Nor do the standards require enrichment or social companionship for elephants.

What’s worse, even these minimal standards of the AWA are not meaningfully enforced. Congress tasked the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) with implementing this law. Still, time and time again, the agency’s own Office of Inspector General (OIG) has found the AWA enforcement to be appallingly paltry. When violations of the minimal standards are documented, the most likely outcome for an exhibitor is a meaningless warning. If they disregard said warning, odds are good the USDA will not take any follow-up action—or that, if it does, it will be in the form of another warning (sometimes even a third warning!) or a fine that is so heavily reduced that, in the words of the OIG, it is treated as a “cost of doing business.”

Minimal Fines and Consequences for Elephant Exploitation

The horrific abuse by Carson & Barnes’ head trainer that was documented on video resulted in a $400 fine. When two elephants were injured after a Carson & Barnes truck crashed and flipped on its side, the USDA fined the company $550. In 2016, the company paid a higher fine after three elephants were injured after escaping and damaging property, but it was still a tiny fraction of the potential penalty under the law. In 2012, the company paid just $3,714 for 10 Animal Welfare Act violations, including yet another escape, as well as public endangerment. Such trivial penalties do nothing to deter violations—hence, yet another elephant escape in 2024.

The USDA is fully empowered to revoke Carson & Barnes’ license to exhibit animals after such an extensive record of violations. But it has refused to exercise this authority. Instead, the agency continues to renew that license.

Nor have efforts to advocate for elephants in the courtroom fared well. Lawsuits seeking recognition of a right to bodily liberty for elephants have failed in the U.S., essentially on the grounds that, while elephants are remarkably intelligent and complex and fare exceptionally poorly in captivity as a result, they aren’t humans. Though courts have the authority, under the common law, to recognize such rights, they’ve declined to do so, instead instructing advocates to go to the legislature. And so they have.

State and Local Advocacy Succeeds in Protecting Elephants

In the face of court refusals and federal government and industry failure, animal advocates have stepped up their legislative efforts—and they’ve met considerable success. In 2024, Massachusetts became the 11th state to restrict the use of elephants and other wild animals in circuses. More than 200 local jurisdictions across the country have done the same. In 2023, Ojai, California, became the first city to “codify elephants’ fundamental right to bodily liberty, thereby prohibiting the keeping of elephants in captive settings that deprive them of their autonomy and ability to engage in their innate behaviors.”

But with hundreds of elephants still held captive without meaningful legal protections—some of them still subjected to grueling travel and performance regimens—the work is not done.

The Role of Every Individual in Supporting Elephant Protection

The good news is that every one of us can play a role in getting us closer to a world in which widespread public awe and respect for elephants is codified into our laws. We can start by not patronizing institutions that profit from elephant suffering and educating our family and friends about these animals and what they endure. We can also reach out to our city council members and county commissioners to ask them to follow in the footsteps of the many jurisdictions that have banned traveling elephant (and other animal) acts.

The Humane Society of the United States (now Humane World for Animals) created an extensive, step-by-step guide to help advocates pass such ordinances in their communities. If your local government has already banned traveling animal acts, or if none come to your town, you could go even further and work to enact an ordinance modeled on Ojai’s that prohibits elephant captivity. Similar measures can be pursued at the state level as well, especially if local jurisdictions within the state have already made strides.

And let’s not forget the possibility of federal protection. Animal protection is one of the few remaining bipartisan issues, and more than 50 other countries have already banned or restricted traveling animal acts at the national level. In 2022, despite extensive legislative gridlock, animal advocates successfully persuaded Congress to enact the Big Cat Public Safety Act, which prohibits private ownership and public interactions with big cats. Bills to ban traveling wild animal acts have been introduced at the federal level in the past and, with persistence, could meet similar success.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

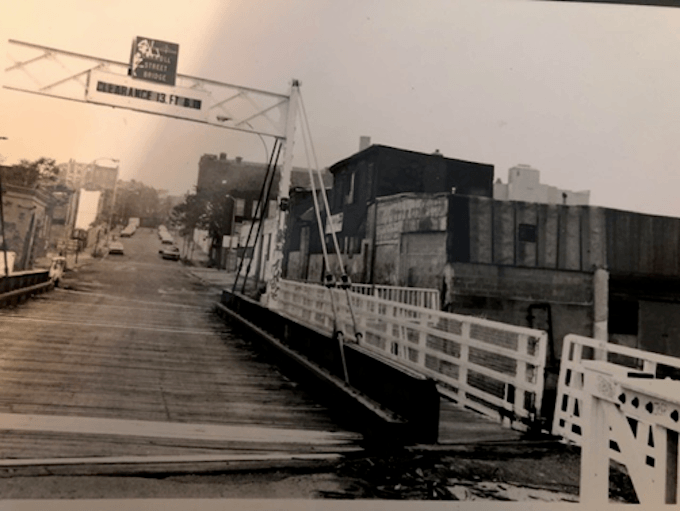

Wild Dogs of Brooklyn

Just after New Years in 1979 I moved from the East Village to Brooklyn. Carol was pregnant, but her cramped digs on Carroll Street would not accommodate us. We found a loft building, very rare in Park Slope, on the lower margins of the neighborhood near 4th Avenue, a six lane artery running from downtown Brooklyn to Bay Ridge. Across the avenue a ruined commercial zone of dilapidated red brick structures of unknown provenance, mostly abandoned, spread over both sides of the Gowanus Canal, described in the tabloids as “the most polluted body of water in the nation.”

Creating a home in the loft was a stretch, financed on a limited budget, the $12,000 I’d saved from the combat pay of a first lieutenant in Vietnam, augmented by disability payments. We had a raw space 30 x 100 feet to enclose, electrify and plumb, roughly half the second floor off the center stairwell in the warehouse of a former wholesaler. Two existing partitions in lacquered beadboard divided the space in three sections, front, rear and center, and absorbed whatever light the windows on the street side provided, and photos show the interior was always dark even after a large metal door over an opening used for uploading deliveries from an empty lot along the side wall was replaced with a pane of glass half the dimensions of a typical storefront.

Plumbing was a major challenge, and I gaped in awe as our guy melted lead for joints stuffed with oakum in steel drainpipes lowered into the building’s basement to enter the urban sewage. We found sinks for the kitchen and bathroom, and a gas range and fridge in a used fixtures outlet on Delancy Street in Manhattan. And we used my brother’s econovan to transport a cast iron tub we found dumped on a street corner in the Bronx. Finding matching claw feet to support it seemed improbable until I picked through a brim-filled bin with demolition discards in a salvage yard on the fringes of Red Hook. I picked up translucent glass bricks in the same yard. These formed a rear wall in the bathroom to allow some natural light after windows along the building’s rear wall were obscured by the narrow corridor we erected leading to a fire exit. The front beadboard partition formed a T and one side became our bedroom, the other a study, dappled with daylight through four large greasy windows facing the street. To a working chimney we attached a Ben Franklin Stove in front of our bed, acquired how I no longer recall, but fueled by firewood consigned periodically in face cords from a Long Island supplier and hoisted to our loft on a freight elevator accessed from the sidewalk. A large gas blower suspended from the ceiling in the central space provided most of the heat.

Additional bedrooms were roughed out behind the beadboard to the rear paralleling the kitchen wall, for two kids, the child we were expecting and Carol’s daughter, Sarabinh, then six, in joint custody between her father’s nearby apartment in the upper Slope and our loft. A hodge podge of chairs, couches and hanging house plants was arranged near the large sidewall window and a hammock of acrylic fiber stretched between two lally columns that helped support the floor above us. A ballet bar was installed along the rear beadboard wall, which I used for stretching, and in front of that I laid my tumbling mat for acrobatics. In New York at the time, legal occupancy in a loft building required AIR – Artist in Residence – status. As a sometimes student of Modern Dance and other movement disciplines, my certification as a dancer was granted under the signature of Henry Geldzahler, the then reigning New York City Culture Czar. A small sign with AIR in black lettering was affixed near the building’s front door, and applied collectively to all the residents split among six lofts, mostly painters and a sculptor. In December that year, we hosted a party, a belated celebration of Carol’s birthday in October and Simon’s birth in August. It would also honor ‘Lofts Labors Won.’

The following August with our one year old in tow, we departed the city on Carol’s literary mission, destination Castine, Maine. Our first stop was at a commune near Brattleboro, Vermont, where old movement cronies of Carol’s had gone back to the land in the late sixties. They were an ingrown, argumentative lot which, on their periphery, included two columnist for the Nation in private summer residence. For three days we labored and convived with these old comrades, one of whom formerly in the Weather Underground and ensconced there pseudonominously, was still wanted by the FBI. Carol phoned to Castine to confirm our arrival time, and was informed by Mary McCarthy that the visit was off. This was to have been the first face to face with the subject of the biography Carol had just begun, postponed now because Mary’s husband had broken his leg falling off a ladder while cleaning the gutters.

A majority of Carol’s forebearers had settled in Maine from colonial times, and a great aunt whose story she greatly revered was buried there in the family plot, along with a host of other Brightmans and Mortons. The Maple Grove Cemetery played like Thornton Wilder country. So, Maine trip on. While passing from New Hampshire into Maine we stopped to orient ourselves at a Visitor’s Center, where I haphazardly grabbed a few brochures, including a pamphlet of real estate listings. Except where work was concerned – I was also in the midst of a book project – Carol and I weren’t planners; we were impulsive doers. On occasion we daydreamed out loud about finding a place “in the country,” never projecting the fantasy beyond the nearer regions of upstate New York. One real estate offering showed an old federal house on a saltwater farm near where we were now bound. And when our route took us past the office of the agent representing the property, we joked that it was fated. We’d go check it out, “but we’re not serious,” Carol disclaimed.

The house, which had been empty for a quarter century, was structurally sound with a good roof, and came with several outbuildings, including a barn and the middle twenty acres of the old homestead, in field and woodlot. An old bachelor farmer had lived there without indoor plumbing or electricity until the early sixties, then in the local tradition took refuge with a younger family for his final years. Without thinking that this would become the rural equivalent of our recent urban undertaking, another residence to be mounted from scratch, we focused on the $45,000 asking price and bought it on the spot. We had to lean on friends and relatives to assemble the ten grand downpayment, and we had a rough ride to get a mortgage approved, but while we put that home back together, it became our summer escape for the next six years.

There were always wooded areas where I grew up on Long Island, and I was drawn to them. I’m sure looking back they were enlarged in a child’s eyes, and minuscule when compared to our twenty acres of tall pines and spruce that blended seamlessly into miles of contiguous woods where I now wandered on frequent constitutionals. The solitude was compelling and a balm to my mental wellbeing. That I would soon find on the mothballed Brooklyn waterfront a far from bucolic but equally suitable option for these frequent bouts of solitary wool gathering, not for only three months, but for nine, astounds me still.

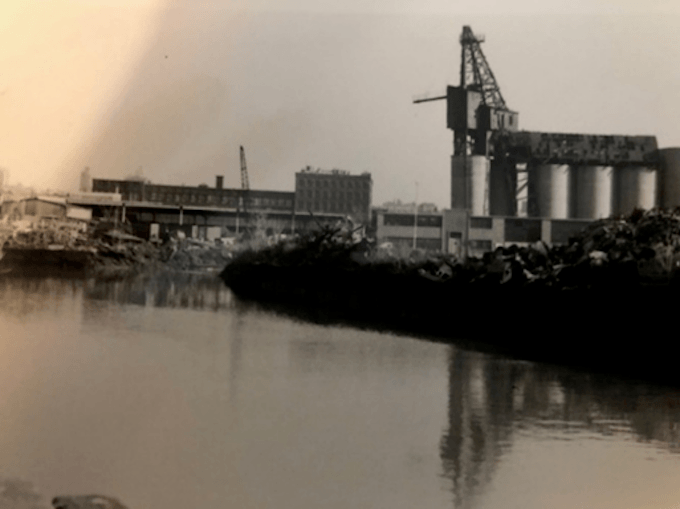

Exploring the environs of the Gowanus was my first step toward Red Hook. Plans for the rehabilitation of the canal would become a topic for a deep investigative dive by Carol and me into the history of the canal from its idyllic indigenous setting as a healthy estuary where foot long oysters grew, to the contemporary canal in decay which civil minded community leaders in Carroll Gardens, the largely Italian American neighborhood bordering the other side of the patch surrounding the Gowanus, had long in their sights for cleanup and development. We dug into that story for a couple of years, wrote a serious proposal, but nothing ever came of it. Why, I no longer recall? When you live by your pen engineering projects from elevated states of endorphin fueled enthusiasm that never reach completion, certainly for me and Carol also, was a not infrequent occurrence. A colorful sidebar here would include the presence of the Joey Gallo crime family among these mostly silent empty blocks, and while remaining agnostic as to its veracity, news reports on the doings of the New York Mob if the Gowanus warranted a mention might note the neighborhood legend that held the canal was where the wise guys dumped the bodies of their rivals.

We’d soon settled into the neighborhood where a number of familiars from the anti-Vietnam War movement had also settled to start their own families. Carol was teaching remedial classes at Brooklyn College which had initiated open admissions, at the same time peddling articles, to a variety of outlets. I still commuted to my non-profit, Citizen Soldier, in the Flat Iron Building on lower Fifth Avenue in the city until early 1982. It was a movement job at movement wages, advocating for GIs and veterans around a host of issues, most recently the alleged health related illnesses from exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam, and for vets who participated in Atomic Tests during the fifties, from radiation. After twelve years of full time activism primarily related to Vietnam, the move to Brooklyn had severed that umbilical and I was ready for a change, which initially took the form of painting someone else’s living spaces and querying magazines for assignments. Apart from family responsibilities, my time was my own.

When Simon turned three, we enrolled him in the Brooklyn Child Care Collective, one of those alternative institutions organized by lefties of our generation. It was located a fair piece from the loft near Grand Army Plaza. Shaded under the concrete infrastructure of the Williamsburg Bridge in Manhattan I found a shop to custom build a bike adapted to Brooklyn’s rough streets: ten speed, but thick tires, straight handlebar and a large padded seat. With Simon strapped into a red toddler carrier mounted over the real wheel, I peddled him to day care most mornings.

The exploration of the Gowanus along our stretch of 4th Avenue from 9th Steet to Union Street, and taking in the Carroll Gardens neighborhood where many of our informants resided, began during Carol’s and my investigative project. Often, however, I would walk these blocks on my own, camera at the ready. My way of seeing the material wreckage strewn along the banks of the canal was informed by the work of Robert Smithson’s, The Monuments of Passaic. Smithson sited installations “in specific out door locations,” and is best known for his Spiral Jetty on the Great Salt Lake of Utah. In his article for ArtForum illustrated with six bleak black and white photographs Smithson described “the unremarkable industrial landscape” in Passaic, New Jersey as “ruins in reverse…the memory-traces of an abandoned set of futures.” This was the perfect conceptual framework for reflection on what I was looking at. Embedded in Smithson’s musings, his “set of futures” perhaps made predictable the upscale development that would totally transform the blocks around the Gowanus forty years later; but that’s another story.

In an earlier time, the canal had provided the perfect conduit for the materials from which the surrounding neighborhoods had been constructed. A small number of enterprises, the Conklin brass foundry, a depot for fuel storage, were still in operation but the vast acreage that once served some productive purpose was littered with industrial waste and the shells of abandoned buildings, some capacious like a former power plant. Idle cranes and derricks stories high stretched their necks over the canal like metallic dinosaurs. At three compass points along the horizon billboard sized signs on metal grids perched on spacious roof tops – Kentile Floors, Goya Foods, Eagle Clothes – were markers of manufacturing life, but if still active I never learned.

With my new bike, I began to wander farther afield, making stops along Court Street, the main drag in Carroll Gardens where you’d find an espresso stand where Italian was spoken that seemed to have been imported intact – baristas to stainless counter top – from Sicily. If only for the historical record, I insert here the presence of two storefronts that were likely unique throughout the entire city. Pressed tin sheets were still common for ceilings in commercial buildings in New York, and spares in a variety of designs filled upright bins at a specialty shop on Court Street. In the same block locals who kept roof top flocks of pigeons could buy replacement birds and the feed that sustained them.

The pigeon shop in particular conjured scenes from the Elia Kazan film of Budd Schulberg’s On the Waterfront in which Brando tends his own flock on the roof of a tenement, the typical dwelling for the families of stevedores who worked the Brooklyn docks, once the most active waterfront in the nation. After World War Two, container ships were rapidly replacing the old merchant freighters with their cargo holds, and increasingly making landfall, not in Brooklyn, but across the harbor in New Jersey.

Frozen in time, the old Brooklyn waterfront, adjacent to the neighborhood known as Red Hook, now became the cycling grounds for my long solitary ruminations. Access to the area was usually across the swing bridge over the canal on Carroll Street which, after emerging under the Gowanus Expressway, dead ended on Van Brunt Street, a long artery that ran for nearly two miles parallel to the string of wharfs that jutted into the harbor, terminating before an enormous stone warehouse dating from the Civil War. An old wooden wharf, long and wide, ran that building’s length on the water side, its thick rotted planking making an obstacle course I often ventured over despite the warning sign to keep off.

I could ride Van Brunt and up and down its side streets for an hour without ever seeing another person or being passed by a motor vehicle. Many of the roadways were paved with cobble stones, safely navigated by my bike’s thick tires. As with select locations on the Gowanus streets, a sprinkle of diminutive dwellings mysteriously still inhabited and surprisingly well maintained co-existed with the adjoining wasteland, the hold outs from more stable and more populated times. There was a storefront selling live chickens that, when open, filled small wooden crates on the sidewalk. And at the end of one particularly isolated block a small two story clapboard-sheathed home behind a chain link fence and next to a vacant lot, but where several late model gas guzzlers were parked at street side, I actually saw live chickens in the yard pecking at the ground. If I rode down Wolcott Street to the water’s edge, I’d have a close up 400 yards across Buttermilk Channel of Governor’s Island, a military installation for almost two centuries, and since the new millennium the site of a public park accessible only by ferry. Inhabited all those years, generations of soldiers had a front row view of the rise and fall of the Brooklyn waterfront.

The Loft in 2024.

Just before Christmas on an overcast day I was riding along one of these interior streets feeling hemmed in by the ghostly emptiness surrounding me between shuttered buildings to one side and the old dockside secured behind walls of security fencing on the other, when a pack of feral dogs appeared several hundred feet to my front. There was a wooden creche at road side – clearly the devotional installation of a local parish I could never identify – with oversized statues of the cast at the Manger that had become the territorial shelter that four gum baring yelping canines were now furiously defending. As they began to rapidly close on me, I swung my bike one-eighty and hit the peddles with a sprinter’s gusto, soon realizing I could never outrun them. In an instant I stopped my bike, dismounted and faced the charging pack, waving my arms high above my head growling and barking as loudly and aggressively as I could. They stopped in their tracks, turned in formation and low tailed it from whence they’d come. Not to push my luck, I did the same. Barely through the door back home, still in the flush of wonder and exhilaration, I yelled to Carol, “you’ll never believe what just happened to me.”

All photographs by Michael Uhl.