In the centuries since the first coffeehouse was opened in Istanbul in 1554, Turkish coffee has brought together people of different classes, cultures and ranks and helped shape politics and lifestyles, Ali Çaksu, visiting professor of history and political thought at Germany’s Ludwig Maximilian University, told a scientific forum at the University of Sharjah last week.

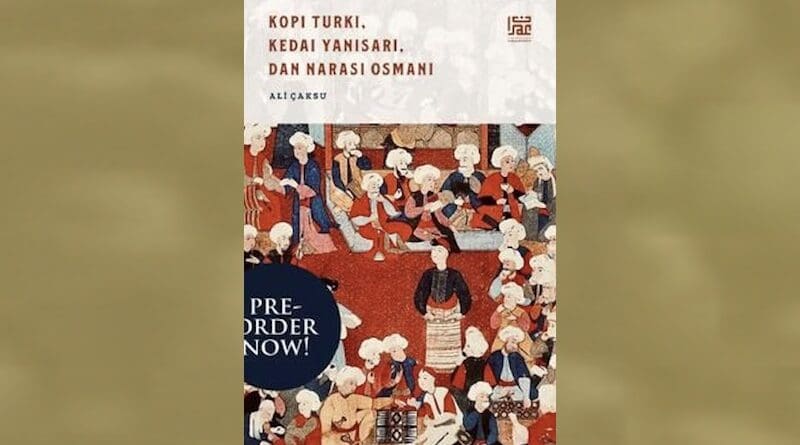

Prof. Çaksu was presenting to the forum his new book titled Kopi Turki, Kedai Yanisari, dan Narasi Osmani, Indonesian for ‘Turkish Coffee, Janissary Café, and the Ottoman Narrative’ published in April 2025 by Umran Press in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The two-word phrase in the book’s title ‘Kedai Yanisari’ is an Indonesian appellation associating ‘Yanisari’ or Janissary, part of the elite infantry force of Ottoman sultan’s palace guards, with ‘Kedai’ or Café – an indication of the influence the beverage exercised in the Ottoman era.

“Turkish coffee is not merely a drink associated with caffeine and known to keep tiredness at pay and stimulate heart and mind,” said Prof. Çaksu. “Turkish coffee has been a political, cultural and mystical drink since the first café appeared in Istanbul in the 16th century, transforming leisure, lifestyle, cultures and influencing politics.”

In less than a century, parallels to the first coffee house in Istanbul were available in the larger Middle East and many European countries. Turkish coffee could be found in London, Venice, Marseille, Vienna, Paris among other European metropolises. In the Middle East, coffeehouses were established in Damascus, including the then cosmopolitan city of Aleppo; Cairo, where coffee shops opened in streets adjacent to the Islamic university of Azhar; in Baghdad; and even in the Muslims’ holiest city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia.

The forum brought together scholars with an interest in Arab and Muslim civilization from different parts of the world. It was convened by Sharjah International Foundation for the History of Arab and Muslim Sciences (SIFHAMS).

“The history of Muslim sciences cannot be fully appreciated without recognizing the pivotal role of cultural practices and social institutions, among which the advent of coffee and the rise of coffeehouses which stand out as particularly significant,” said University of Sharjah professor of Islamic studies, Mesut Idriz, who is also SIFHAMS’ director and the forum’s organizer.

Turkish coffee, which originated in Yemen through the practices of Sufi mystics, was accompanied by the emergence of the qahwa khāna, Turkish for coffeehouse which Prof. Idriz described as “an institution that transcended its immediate function as a place of refreshment … and became a vital forum for intellectual exchange, often frequented by scholars, poets, travelers, and merchants.”

Prof. Çaksu’s book highlights the interesting and rich relationship of the drink to politics and religion. He suggests that Turkish coffee was a “political drink” or was politicized in its earliest time in Istanbul, “because political meanings were often attached to the drink and the places where it was consumed.

“In those times political discussions took place in coffeehouses and they included criticism of policies, appointments and dismissals, corruption of politicians as well as rumors. Such conversations disturbed rulers and officials who were quite suspicious of them and perceived them as a threat to the existing socio-political order.”

The rapid spread of coffee shops emulating the first coffeehouse in Istanbul was not always smooth and peaceful. Many in Europe saw the coming of coffee as part of fresh efforts by the Ottoman Empire at “Islamization”. In the Middle East, which was then still part of Ottoman dominions, the prevalence of coffeehouses was seen as an attempt at “Ottomanism,” a political ideology meant to unify diverse ethnic populations of Ottoman Empire under Ottoman identity. Muslim clergy, who thought of it as alcohol, initially forbade Muslims from drinking it.

Prof. Çaksu reiterated the line “New Liquors brought in new Religions,” a 17th century phrase often mentioned by scholars when researching the impact of new beverages. He said the same phrase was frequently cited, when Turkish-style coffeehouses mushroomed in Europe, as evidence of “an invasion by Islam” on the back of a cup of coffee.

He noted that Europeans feared the coming of coffee to their lands could be the harbinger of new social habits that would introduce Islamic religious practices to what was then a purely Christian society.

When it first arrived, people in many European countries branded Turkish coffee as “unchristian,” said Prof. Çaksu. He mentioned how American literary icon, Mark Twain, was disappointed with Turkish coffee and quoted him as saying, “Of all the unchristian beverages that ever passed my lips, Turkish coffee is the worst.”

Christian Europe was uneasy with the newcomer “Turkish coffee” as it was associated with “the Muslim infidels with whom Christians had been at war for centuries,” Prof. Çaksu noted.

Turkish coffee was “Satan’s drink or drink of the devil,” noted Prof. Çaksu, adding that the expression “Satanick Tipple” was the first line in the notable piece of satirical writing titled ‘A Satyr against Coffee’ by the 19th century English writer Samuel Butler in which he blasted the burgeoning coffeehouse culture of the time.

In both East and West, many found in the burgeoning coffeehouses a center of sedition and a hub for fomenting anti-religious sentiments. Though Prof. Çaksu had more to say about how the new drink was received in Europe, he did mention that Muslim clergy were unhappy with its popularity, equating Turkish coffee with alcoholic drinks like wine, which Islam forbids. However, added Prof. Çaksu, Muslim scholars relented and issued fatwas (religious decrees) making coffee a permissible drink.

But in Europe Turkish coffeehouses were met with suspicion and seen as a rendezvous for subversive elements to hatch conspiracies on rounds of drinking coffee. Authorities in several European countries saw the advent of coffee as “more dangerous than gunpowder,” he said.

In his book Prof. Çaksu writes, “That is why the authorities often closed down and sometimes even demolished coffeehouses, which they saw as centers of sedition. In addition to the official disdain of coffeehouses, some jurists and religious leaders criticized and condemned coffeehouses and coffee and even issued decrees against coffee and declared it forbidden on religious grounds.

“When the Turkish coffee spread from Istanbul and Cairo to Southern and Western Europe, initially it faced … negative reactions. The drink was considered Turkish, Arabic or Muslim and thus unchristian, heathenish, or satanic. The coffeehouses, too, got their share: just like in Istanbul, in Britain they were also often associated with political subversion and sedition and became targets for official blame and suppression.”

For instance, in England, he said, some branded Turkish coffee “Mahometan berry” in a bid to relate it to Ottoman Empire’s conquests which usually resulted in large-scale conversions to Islam. Some even found the presence of coffeehouses a threat to “Englishness.”

“Some associated Turkish coffee with sexuality, linking it to a surge or drop in sexual desires. Some saw Turkish coffeehouses as likely places to encourage conversion to Islam, and were even said to be part of Republican conspiracy of the 1650s aimed at introducing Islam as a national religion in the U.K.”

In his book, Prof. Çaksu scours literature of various European nations to see what their literary figures had to say about Turkish coffee. Literature mirrors social reality, he affirmed, adding that literary texts reflect cultures, lifestyles and even the type of politics prevalent at the time of writing.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 –1750), a German composer and musician of the Baroque period, Prof. Çaksu went on, “had a Kaffeekantate (Coffee Cantata) composed probably between 1732 and 1735. The cantata suggests that in eighteenth-century Germany, coffee drinking was considered a bad habit.

“Sometime later in Germany, Karl Gottlieb Hering (1766-1853) warned people (and children) against this “Türkentrank” (“Turkish drink”) in his Kaffeelied (“Coffee Song”) for children. For him, the Turkish drink was not good for children, because it could weaken the nerves and make one pale and sick.”

Frederick the Great of Germany, Prof. Çaksu claimed, was so against coffee and he attempted to outlaw it outright in favor of beer in September 1777. Frederick, he said, “required all coffee sellers to register … and ordered soldiers to work as sniffers, roaming the streets to detect any contraband coffee roasters.”

For long, Prof. Çaksu pointed out, coffee was considered a Turkish and Muslim drink in Europe, evidence the negative appellations given to it in the literature like “Turkish berry, Arabian berry, or sometimes Mahometan berry.”

The wide spread of Turkish coffeehouses led to two different views and mindsets about its consumptions and the issuing of two historically important petitions in England in the 17thcentury. The first by women who poured scorn on all-male coffeehouses, branding the drink as “heathen” and “abominable”, and alleging that it caused “impotence”. The second petition was a retort by men to refute claims made by women. The men’s petition described the drink as “innocent” and referred it as “that harmless and healing liquor.”

However, Prof. Çaksu said coffee did good service for the dissemination of Turkish culture and lifestyles. Once widely accepted, Turkish coffee-related customs and symbols were embraced.

“Coffeehouse keepers often wore turbans as an advertising device. Many coffee houses in London and Oxford adopted the name Turk’s Head, Sultan’s Head or took the names of famous Ottoman rulers such as Murad the Great,” he stressed, confirming that the “signs for coffeehouses often displayed a symbol of a turbaned Turk, Turk’s head, or a coffee pot. Even today in Britain some cafes, restaurants, bars, and clubs bear the name Turk’s Head.”

Asked to summarize in his opinion the good things Turkish coffee has done to Europeans, Prof. Çaksu said, “Before the arrival of Turkish coffee, Western Europe did have some places of socialization like pubs where people met. However, unlike alcoholic drinks, coffee and coffeehouses brought a sort of sobering effect. Thus, for instance, in Britain coffeehouses were sometimes called penny universities or citizens’ academy, since for the price of a penny a man could buy a cup of coffee and join the discussions on a variety of topics.

“Turkish coffeehouse frequenters would learn a great deal from friends, strangers, learned people, travelers and soldiers returning home. Furthermore, like in Istanbul, some coffeehouses in London too fostered political opposition and attracted the wrath of the authorities.”

Turkish coffee is the beverage that is steeped in tradition, with UNESCO inscribing it in its Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2013. Even its grounds have been found to have mystical powers as they have led to the emergence of one of the world’s most intriguing and most widely used fortune-telling practice.