Sixteen years to the day that Hurricane Katrina made landfall, Hurricane Ida struck at Port Fourchon, La., on Aug. 29, as a Category 4 hurricane with 240 kilometres per hour winds. Given the date and location of the area affected, Katrina and Ida comparisons are being made.

While no two disasters are the same, looking at differences between past and present disasters can help us to better understand what is needed to prepare for future disasters. As a professor of emergency management, I was on the ground in New Orleans in the aftermath of Katrina, making observations to study aspects of the hurricane’s impact and hurricane evacuations.

Given the scope of the emerging impacts of Hurricane Ida, we see that while this is not a repeat of a Katrina disaster, questions are being raised about the effect of climate change and the resiliency of lifeline infrastructure like electricity.

Remembering Katrina

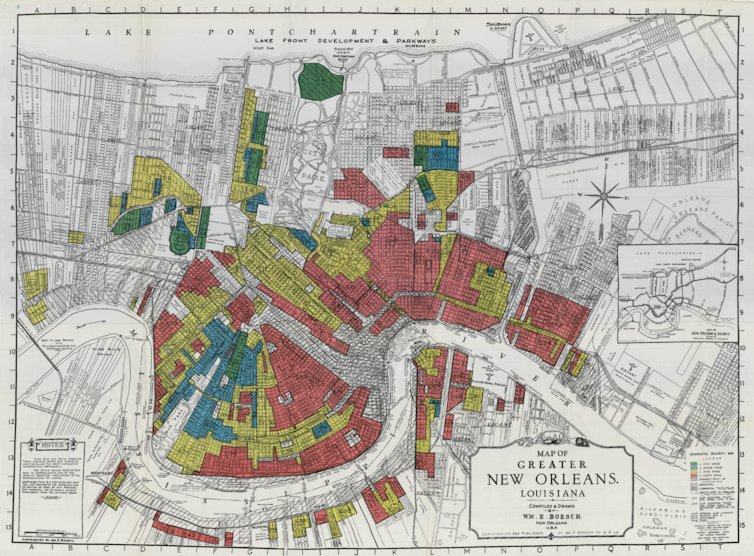

When Hurricane Katrina made landfall as a Category 3 hurricane in 2005, its associated storm surges were among its most significant impacts. The levees that separated New Orleans from Lake Pontchartrain failed. Katrina’s toll was 1,833 killed with US$163 billion in economic losses, making it the costliest weather disaster in the past 50 years.

In looking back at Katrina, forces of nature were not the only causative factors for the disaster. Human-caused circumstances, such as a history of economic and engineering decisions that over time replaced natural coastal wetland buffers against storm surges with a 120-kilometre long industrial canal, were in part to blame for the disaster.

In addition, numerous disaster response debacles complicated the immediate aftermath of Katrina. The disaster exposed racial- and class-based segregation that resulted in disproportionate disaster impacts being felt by racialized populations. What started as a natural disaster played out more like a complex humanitarian emergency.

As the aftermath of Hurricane Ida continues to play out, it remains to be seen if the disaster recovery and the economic losses will approach those of Katrina.

The damage caused by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward in April 2006. (Jack Rozdilsky), Author provided

Differences in hurricane behaviour

A hurricane’s behaviours related to disaster damage include the combination of the effects of high-speed damaging winds, intense periods of rainfall and storm surge flooding in low lying coastal areas.

Katrina’s behaviour is remembered for its devastating water-related hazards with storm surges inundating New Orleans neighbourhoods such as the Lower Ninth Ward.

For Ida, the entire breadth of the storm’s wind field stood out as significant. The storm’s behaviour will be remembered for its wind-related hazards. Ida had a slow path of inland movement with highly destructive sustained winds of 200 kilometres per hour for eight hours over a 120-kilometre long path through portions of Jefferson and LaFourche parishes.

In 2005, Katrina crossed a cooler water column in the Gulf of Mexico as it neared the shore, weakening it from a Category 5 to a Category 3 storm at landfall. In 2021, Ida did not encounter any cooler waters, resulting in its rapid intensification. Rising water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are related to climate change.

New preparedness challenges

Unlike the situation in 2005 with Hurricane Katrina, the levees and drainage systems protecting New Orleans held up under the stress of Ida’s storm surge. Since Katrina, the U.S. federal government has spent $14.5 billion on levees, pumps, seawalls, floodgates and drainage. Apparently, in the case of Hurricane Ida, that investment in hazard mitigation paid off.

However, while preparations to protect against Katrina-like storm surge flooding appeared to be successful, other aspects of preparation did not fare as well. The region’s electrical grid did not remain functional under the hours of sustained hurricane force winds. Local utilities serving Louisiana said it would take days to assess the damage to their equipment and weeks to fully restore service across the state as problems with the electrical grid continue. All the eight main transmission lines bringing electricity from power plants into New Orleans were knocked out, and more than one million people remain without power three days after landfall.

Without power, the situation is becoming increasingly desperate. As one example of the collateral damages related to a lack of electricity, the gasoline distribution system imploded. As conditions degrade due to a prolonged electrical outage, people who did not evacuate during the storm may be forced to, and those who evacuated will be prevented from returning.

Looking at the aftermath of Hurricane Ida illustrates how climate change is making hurricanes more devastating. While studies continue to assess the climate change contribution to hurricane intensity, there is little doubt that the increased frequency and intensity of hurricanes impacting the Gulf Coast of the U.S. is being influenced by global warming.

Sixteen years of additional climate change since Hurricane Katrina adds to preparation needs. Even if we are doing better with challenges like protecting against storm surge flooding, the impacts of future hurricanes call for additional measures. These include increasing the resiliency of our infrastructure to better meet the risks of a changing climate.

Associate Professor of Disaster and Emergency Management, York University, Canada

Disclosure statement

Jack L. Rozdilsky is a Professor at York University who receives funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as a co-investigator on a project supported under operating grant Canadian 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Rapid Research Funding.