(The Conversation) — The German peasants were among the first to try to unlock the revolutionary potential of Reformation teachings to fight social and economic injustice.

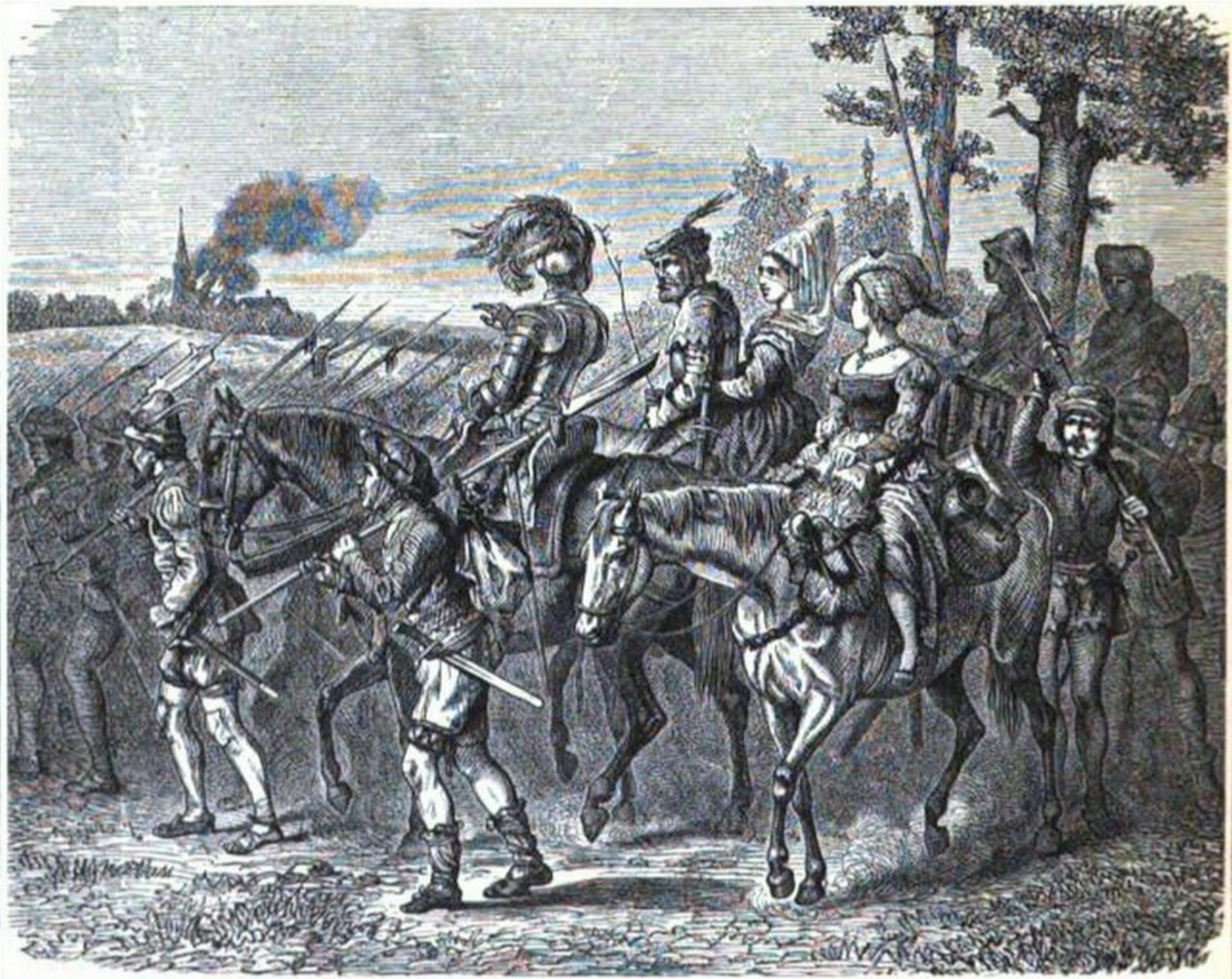

A sketch of groups of peasants wandering around the countryside during the German Peasants' War. (Warwick Press via Wikimedia Commons.)

Michael Bruening

February 26, 2025

(The Conversation) — Five hundred years ago, in the winter of 1524-1525, bands of peasants roamed the German countryside seeking recruits. It was the start of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution. The peasants’ goal was to overturn serfdom and create a fairer society grounded on the Christian Bible.

For months, they seized their landlords’ monasteries and castles. By March 1525, the peasant armies had grown to encompass tens of thousands of peasants from Alsace to Austria and from Switzerland to Saxony.

The peasants had economic grievances, to be sure, but they also drew inspiration from the message of freedom, or “Fryheit” in German, being preached by theologian Martin Luther, who had recently launched the Protestant Reformation

Luther’s rejection of the peasants’ cause, however, would help lead to their crushing defeat.

I am a scholar of the Reformation, and I included the peasants’ list of demands in my book on the debates of the era. The question of the legitimacy of the peasants’ uprising was one of the most consequential debates of the era.

Luther’s message of freedom

In 1517, eight years before the German Peasants’ War, Luther launched the Reformation with his 95 Theses. The theses reflected Luther’s belief that the pope and the Catholic Church were preying on the poor by selling them indulgences, taking their money for a false promise that their sins would be forgiven.

Luther taught instead that God freely forgives the sins of believers. In one of his most famous early treatises, “The Freedom of a Christian,” written in 1520, Luther argued that because they are saved or “justified” by faith alone, Christians are entirely free from the need to do works to merit salvation. This included fasting, going on pilgrimages and buying indulgences.

Luther’s attacks on the Catholic Church, clergy and monks quickly grew more vehement. He and his allies lambasted them for fleecing the peasants and the poor through usury, a practice of lending money at high rates of interest. Since the Bible provided no support for such practices, they argued, the poor should be free of them.

The Twelve Articles

In her 2025 book “Summer of Fire and Blood,” Reformation scholar Lyndal Roper argues that the religious element of the peasants’ war was central. The German peasants were among the first to try to unlock the revolutionary potential of Reformation teachings to fight social and economic injustice.

The peasants’ efforts to do so can be seen in the most important statement of their demands: The Twelve Articles. The articles are rooted in Reformation ideas and demanded, among other things, each village’s right to elect its own pastor and to be exempt from payments and duties not found in the Bible.

A pamphlet that peasants distributed with their Twelve Articles in 1525.

Otto Henne am Rhyn: Cultural History of the German People, via Wikimedia Commons

Most important was the message of freedom in the third article: “Considering that Christ has delivered and redeemed us all, without exception … it is consistent with Scripture that we should be free.” It was a cry for equality based on Christ’s redemption of all, rich and poor alike.

The Twelve Articles were hugely successful, going through 25 printings in just two months. Since the vast majority of peasants were illiterate, this was an astounding number.

For the lower classes, the Reformation promised to break up not just the spiritual monopoly held by the Catholic Church but the entrenched feudal system that kept them oppressed. Their desire for freedom was at the same time a denunciation of serfdom.

The peasants were willing to take up arms to secure their freedom. In winter 1524-1525, the peasants were able to capture castles and monasteries without much bloodshed. But starting in the spring of 1525, the uprising became increasingly violent. On Easter Sunday, the peasants shockingly slaughtered two dozen knights in the city of Weinsberg, Germany. A torrent of bloodshed would follow.

Luther’s rejection of the peasants

Although Luther may have provided the initial inspiration for the peasants, he denounced their revolt in the harshest terms. In his treatise “Admonition to Peace,” Luther complained that the peasants had made “Christian liberty an utterly carnal thing,” which “would make all men equal … and that is impossible.”

Responding to the revolt, Luther produced a tract entitled “Against the Murdering and Robbing Hordes of Peasants.” “Let everyone who can,” he infamously wrote, “smite, slay, and stab” the rebellious peasants. The rulers did just that.

The nobility had been slow to react to the peasants’ initial incursions, but when they finally organized their own armies, the peasants didn’t stand a chance. On the battlefield, the nobles’ cavalry and superior artillery brutally cut down the rebels. Many who escaped the battlefield were hunted down and executed.

The exact number of those killed are not known, but estimates place the number at around 100,000. As Roper notes, “this was slaughter on a vast scale.”

English historian A. G. Dickens famously described the Reformation as an “urban event”, meaning that the movement’s important developments took place in cities. The German Peasants’ War shows the idea to be wrong.

In its first years, the Reformation galvanized the hopes and dreams of Germans in both town and country. To peasants and townsfolk, it seemed to promise the chance for a complete reordering of an unjust society.

Luther’s rejection of the peasants had important long-term consequences. His decision to side with the princes transformed the Reformation from a grassroots movement into an act of state. Everywhere the Protestant reformers went, they sought to work with the proper authorities. The close cooperation of Christian leaders and secular authorities would last for centuries.

For their part, the European peasantry grew wary of the Christian leaders who seemed to have abandoned them. Social uprisings over the next centuries lost the religious character of the 1525 conflict and would climax in the decidedly secular French Revolution.

(Michael Bruening, Professor of History, Missouri University of Science and Technology. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

The Conversation religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The Conversation is solely responsible for this content.

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for PROTESTANT REVOLUTION

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for DIGGERS LEVELLERS

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for PEASANT WAR GERMANY

Marxists.org

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/peasant-war-germany/index.htm

The Peasant War in Germany by Frederick Engels 1850

Jun 6, 2023 ... The Peasant War in Germany was the first history book to assert that the real motivating force behind the Reformation and 16th-century peasant ...

Libcom.org

https://libcom.org/article/third-revolution-popular-movements-revolutionary-era

The Third Revolution: Popular Movements in the Revolutionary...

Jun 15, 2020 ... pdf (17.78 MB). ThirdRevVol2Pt1.pdf (12.23 MB). ThirdRevVol2Pt2.pdf (28.3 MB) ... Audiobook of Murray Bookchin's Ecology and Revolutionary Thought.

![The Snow Queen, by Edmund Dulac [1911] (Public Domain Image)](https://sacred-texts.com/pag/sor/img/snowquee.jpg)