Illustrations: Shira Inbar

OneZero conducted a 10,000-person poll to shed light on the plight of H-1B workers

INTO THE VALLEY

Sarah Emerson Feb 24 ·

This article is part of Into the Valley, a feature series from OneZero about Silicon Valley, the people who live there, and the technology they create.

OneZero conducted a 10,000-person poll to shed light on the plight of H-1B workers

INTO THE VALLEY

Sarah Emerson Feb 24 ·

This article is part of Into the Valley, a feature series from OneZero about Silicon Valley, the people who live there, and the technology they create.

In 2010, Alex left a “pretty small country in Asia” to study computer science at one of America’s elite universities. Alex, who requested anonymity due to the sensitive nature of this story, eventually caught the eye of Microsoft, which sponsored their H-1B visa. Now legally a guest worker in the United States, Alex was one of thousands of foreign employees in a labor pipeline stretching between Silicon Valley and countries like India, China, and South Korea.

Every year, technology giants compete over H-1B visas, and the opportunity to sponsor foreign workers. For these employees, the visa can represent a path to residency, and can mean employment at some of the world’s most high-profile companies. But foreign laborers who enter the program also report feeling like an underclass, with stressful working conditions and discrimination due to their visa status.

Alex successfully petitioned for a green card, earning their permanent residency in 2019. Yet for thousands of workers on H-1B visas, conditions are challenging, and can feel as if they’re designed to keep them silent.

In late 2019, OneZero commissioned a survey in partnership with Blind, an anonymous social networking app that’s widely used by technology employees, to understand the working conditions that H-1B recipients face. The survey ran for two weeks and drew responses from more than 11,500 workers from some of tech’s most notable companies. (Blind verifies the identities of its users based on their company email addresses.) Employees at Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Uber, and Facebook accounted for a quarter of all feedback. OneZero also distributed a Google questionnaire, completed by more than 180 H-1B workers, that asked about salary, demographics, and the respondents’ opinions of the current administration’s immigration policies and rhetoric.

Every year, technology giants compete over H-1B visas, and the opportunity to sponsor foreign workers. For these employees, the visa can represent a path to residency, and can mean employment at some of the world’s most high-profile companies. But foreign laborers who enter the program also report feeling like an underclass, with stressful working conditions and discrimination due to their visa status.

Alex successfully petitioned for a green card, earning their permanent residency in 2019. Yet for thousands of workers on H-1B visas, conditions are challenging, and can feel as if they’re designed to keep them silent.

In late 2019, OneZero commissioned a survey in partnership with Blind, an anonymous social networking app that’s widely used by technology employees, to understand the working conditions that H-1B recipients face. The survey ran for two weeks and drew responses from more than 11,500 workers from some of tech’s most notable companies. (Blind verifies the identities of its users based on their company email addresses.) Employees at Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Uber, and Facebook accounted for a quarter of all feedback. OneZero also distributed a Google questionnaire, completed by more than 180 H-1B workers, that asked about salary, demographics, and the respondents’ opinions of the current administration’s immigration policies and rhetoric.

Graphics: Matthew Conlen

And OneZero spoke to several technology workers who described their H-1B experiences. All of these workers feared the risks that being identified could pose to their personal lives and asked to remain anonymous.

In early 2020, OneZero ran a second poll in order to gauge the sentiment of non-H-1B workers toward those on H-1B visas, asking questions about President Trump’s immigration policies and the visa’s effects on the technology industry. Many of the respondents worked at companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft.

The responses are not a scientific representation of the technology industry as a whole. Rather, they lend a voice to, and shine a light on, a workforce that, according to OneZero data and interviews, can feel muzzled by the conditional nature of their employer-backed visas. They suggest that at some companies, H-1B holders are perceived as outsiders who, while benefiting from the industry’s high salaries and generous perks, are simultaneously hired at lower wages than their U.S. counterparts and are indentured to some of the world’s biggest technology titans.

The anonymous feedback indicates that H-1B workers hold overwhelmingly negative views of Trump’s immigration policies. One-third said they plan to remain in the U.S. after their visa expires. Some also believe they earn less than their peers, though many report having six-figure salaries. Between half and nearly 80% percent of H-1B workers at Amazon, Uber, Facebook, WeWork, and eBay indicated that they feel pressure to outperform their American colleagues. Meanwhile, tech workers not on H-1B visas express largely positive views about workers on H-1B visas.

These responses paint a complicated picture of a system that’s become central to Silicon Valley’s labor pipeline.

And OneZero spoke to several technology workers who described their H-1B experiences. All of these workers feared the risks that being identified could pose to their personal lives and asked to remain anonymous.

In early 2020, OneZero ran a second poll in order to gauge the sentiment of non-H-1B workers toward those on H-1B visas, asking questions about President Trump’s immigration policies and the visa’s effects on the technology industry. Many of the respondents worked at companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft.

The responses are not a scientific representation of the technology industry as a whole. Rather, they lend a voice to, and shine a light on, a workforce that, according to OneZero data and interviews, can feel muzzled by the conditional nature of their employer-backed visas. They suggest that at some companies, H-1B holders are perceived as outsiders who, while benefiting from the industry’s high salaries and generous perks, are simultaneously hired at lower wages than their U.S. counterparts and are indentured to some of the world’s biggest technology titans.

The anonymous feedback indicates that H-1B workers hold overwhelmingly negative views of Trump’s immigration policies. One-third said they plan to remain in the U.S. after their visa expires. Some also believe they earn less than their peers, though many report having six-figure salaries. Between half and nearly 80% percent of H-1B workers at Amazon, Uber, Facebook, WeWork, and eBay indicated that they feel pressure to outperform their American colleagues. Meanwhile, tech workers not on H-1B visas express largely positive views about workers on H-1B visas.

These responses paint a complicated picture of a system that’s become central to Silicon Valley’s labor pipeline.

The H-1B visa system, created in 1990, allows U.S. companies to sponsor 85,000 foreign workers to temporarily perform specialty jobs every year — labor that’s considered “highly skilled” or demands technical expertise. While the H-1B program accounts for less than one percent of the U.S. workforce, it has come under intense scrutiny from the Trump administration, whose “Buy American and Hire American” policy, designed by White House adviser Stephen Miller, has targeted immigrants and deliberately slowed the use of H-1B visas.

Opponents of the H-1B program say it robs opportunities from qualified U.S. workers, often citing the outsourcing industry’s preference for — and exploitation of — South Asian H-1B employees. IT firms have gobbled up visa quotas in recent years, hiring thousands of foreign workers at below market wages to perform services on the cheap for clients such as Apple and Comcast and other companies replacing permanent (and more expensive) jobs with H-1B contractors. In 2014, 13 of the top 20 companies requesting H-1Bs were outsourcing firms.

The outsourcing industry has been hit with several class action lawsuits alleging anti-white discrimination. Former employees at Cognizant, one of the largest of these companies, claimed in a suit last year that they were pushed out and replaced with “less qualified” H-1B workers from India.

As guest workers, H-1B employees lack many of the safeguards afforded to their colleagues, like the freedom to change jobs without having to leave the country or find another sponsor. Recipients may live in the U.S. for three years with the option of a three-year visa renewal, as long as they remain tethered to their employer. Visas are rewarded on a first-come, first-served basis, or through a lottery based on the number of applications submitted to USCIS. Twenty-thousand H-1B visas are reserved for people with a master’s degree and above. Employers may also sponsor H-1B workers for a green card, but for natives of certain countries, wait times can last decades.

“I believe that H-1B employees tend to tolerate more bullshit from managers because they cannot just rage-quit.”

Politically, the H-1B program catches flack from both sides. Often the source of anti-immigrant sentiment, the program is also a target of criticism among labor leaders. “The technology world has specifically used H-1B visas as a way to hollow out careers into short-term contingent jobs,” said Michael Wasser, legislative director at the Department for Professional Employees, a coalition of 24 national unions that includes technology workers. “It doesn’t matter who’s doing the work. If someone can pick up where the next person left off, labor costs stay the same but output continues.”

The program does have one group of steadfast supporters: large tech companies. In 2008, Microsoft founder Bill Gates asked the House Committee on Science and Technology to re-raise the H-1B cap from 65,000 to 195,000. Mark Zuckerberg has similarly lobbied for more permissive immigration standards.

“Ever since Bill Gates testified before Congress, technology leaders have been talking about using the H-1B program to increase employment,” said William Kerr, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society. “But my take is that, in many ways, it is a crude visa.” The lottery system is ineffective, Kerr says, and too often the program is used to recruit lower-skilled workers at a discount.

Opponents of the H-1B program say it robs opportunities from qualified U.S. workers, often citing the outsourcing industry’s preference for — and exploitation of — South Asian H-1B employees. IT firms have gobbled up visa quotas in recent years, hiring thousands of foreign workers at below market wages to perform services on the cheap for clients such as Apple and Comcast and other companies replacing permanent (and more expensive) jobs with H-1B contractors. In 2014, 13 of the top 20 companies requesting H-1Bs were outsourcing firms.

The outsourcing industry has been hit with several class action lawsuits alleging anti-white discrimination. Former employees at Cognizant, one of the largest of these companies, claimed in a suit last year that they were pushed out and replaced with “less qualified” H-1B workers from India.

As guest workers, H-1B employees lack many of the safeguards afforded to their colleagues, like the freedom to change jobs without having to leave the country or find another sponsor. Recipients may live in the U.S. for three years with the option of a three-year visa renewal, as long as they remain tethered to their employer. Visas are rewarded on a first-come, first-served basis, or through a lottery based on the number of applications submitted to USCIS. Twenty-thousand H-1B visas are reserved for people with a master’s degree and above. Employers may also sponsor H-1B workers for a green card, but for natives of certain countries, wait times can last decades.

“I believe that H-1B employees tend to tolerate more bullshit from managers because they cannot just rage-quit.”

Politically, the H-1B program catches flack from both sides. Often the source of anti-immigrant sentiment, the program is also a target of criticism among labor leaders. “The technology world has specifically used H-1B visas as a way to hollow out careers into short-term contingent jobs,” said Michael Wasser, legislative director at the Department for Professional Employees, a coalition of 24 national unions that includes technology workers. “It doesn’t matter who’s doing the work. If someone can pick up where the next person left off, labor costs stay the same but output continues.”

The program does have one group of steadfast supporters: large tech companies. In 2008, Microsoft founder Bill Gates asked the House Committee on Science and Technology to re-raise the H-1B cap from 65,000 to 195,000. Mark Zuckerberg has similarly lobbied for more permissive immigration standards.

“Ever since Bill Gates testified before Congress, technology leaders have been talking about using the H-1B program to increase employment,” said William Kerr, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society. “But my take is that, in many ways, it is a crude visa.” The lottery system is ineffective, Kerr says, and too often the program is used to recruit lower-skilled workers at a discount.

OneZero’s survey confirms that for some workers on these visas, conditions can be stressful, precarious, and degrading. The acute pressures of working on an H-1B visa were brought front and center at a protest last year, held outside of Facebook’s headquarters following the suicide of Facebook engineer Qin Chen in 2019. Though the circumstances around their suicide remain unknown, Chen’s former coworker, who led the protest, told Motherboard that he was standing up for Chinese Facebook employees who felt silenced by their immigration statuses.

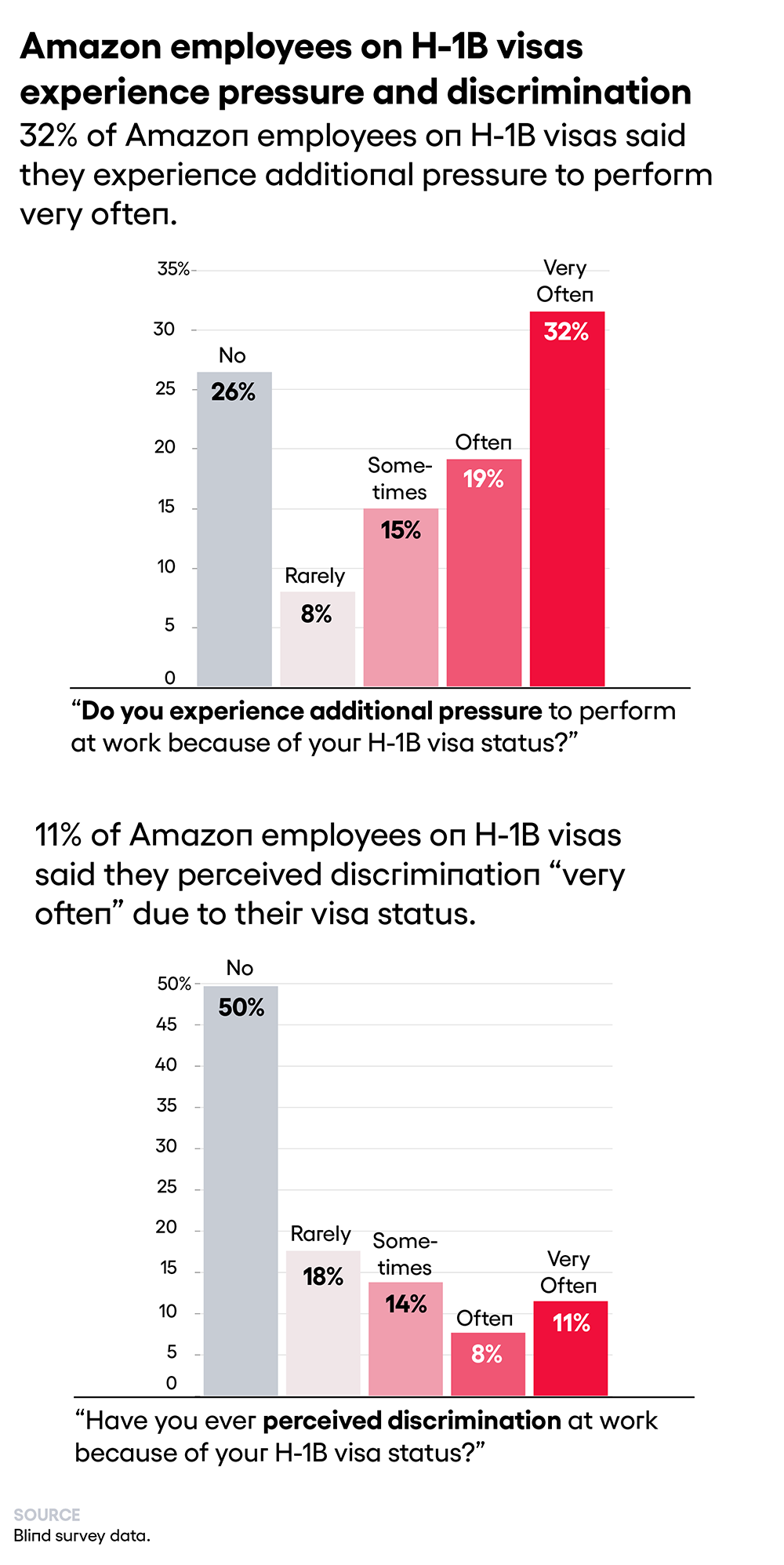

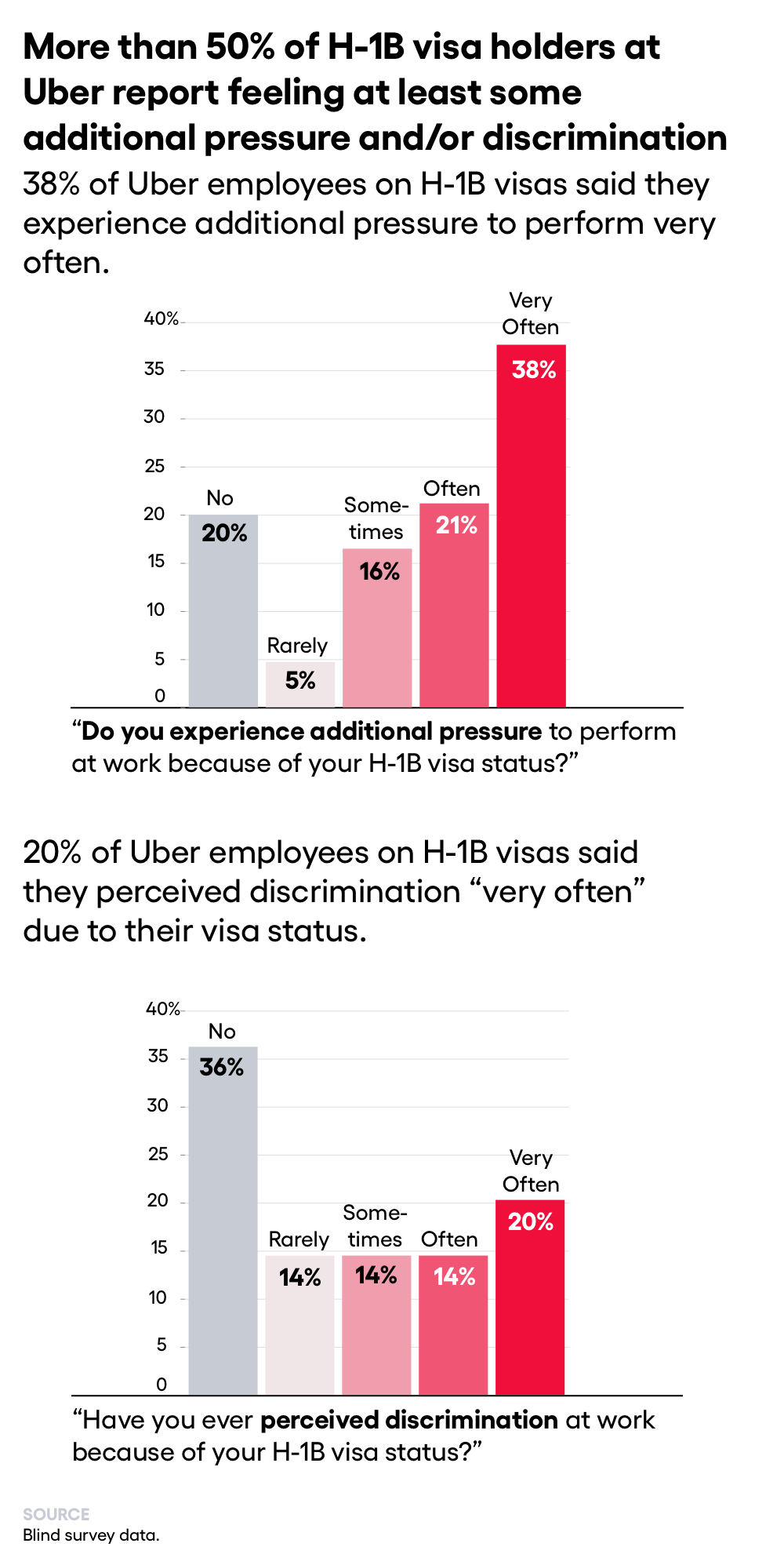

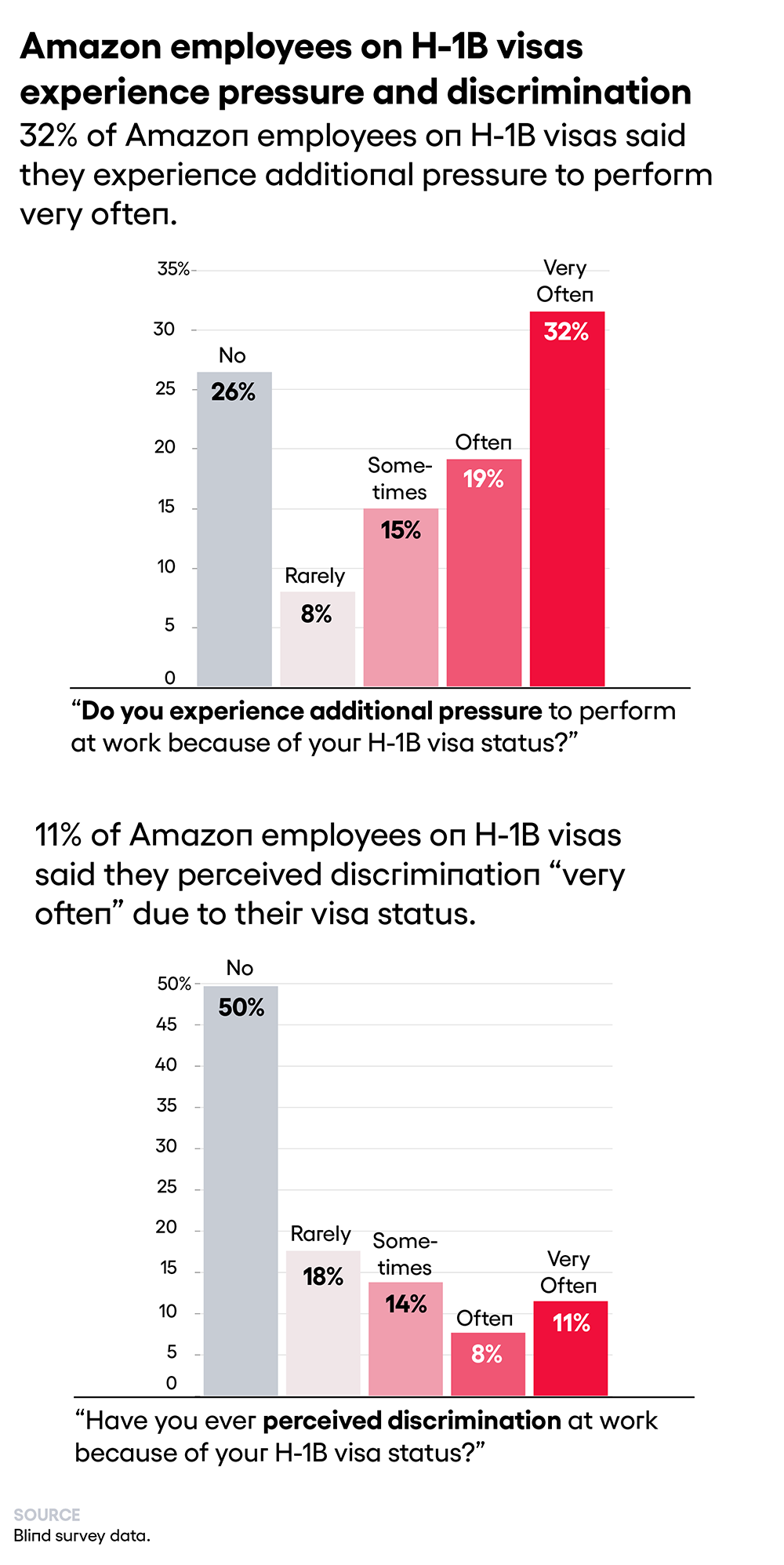

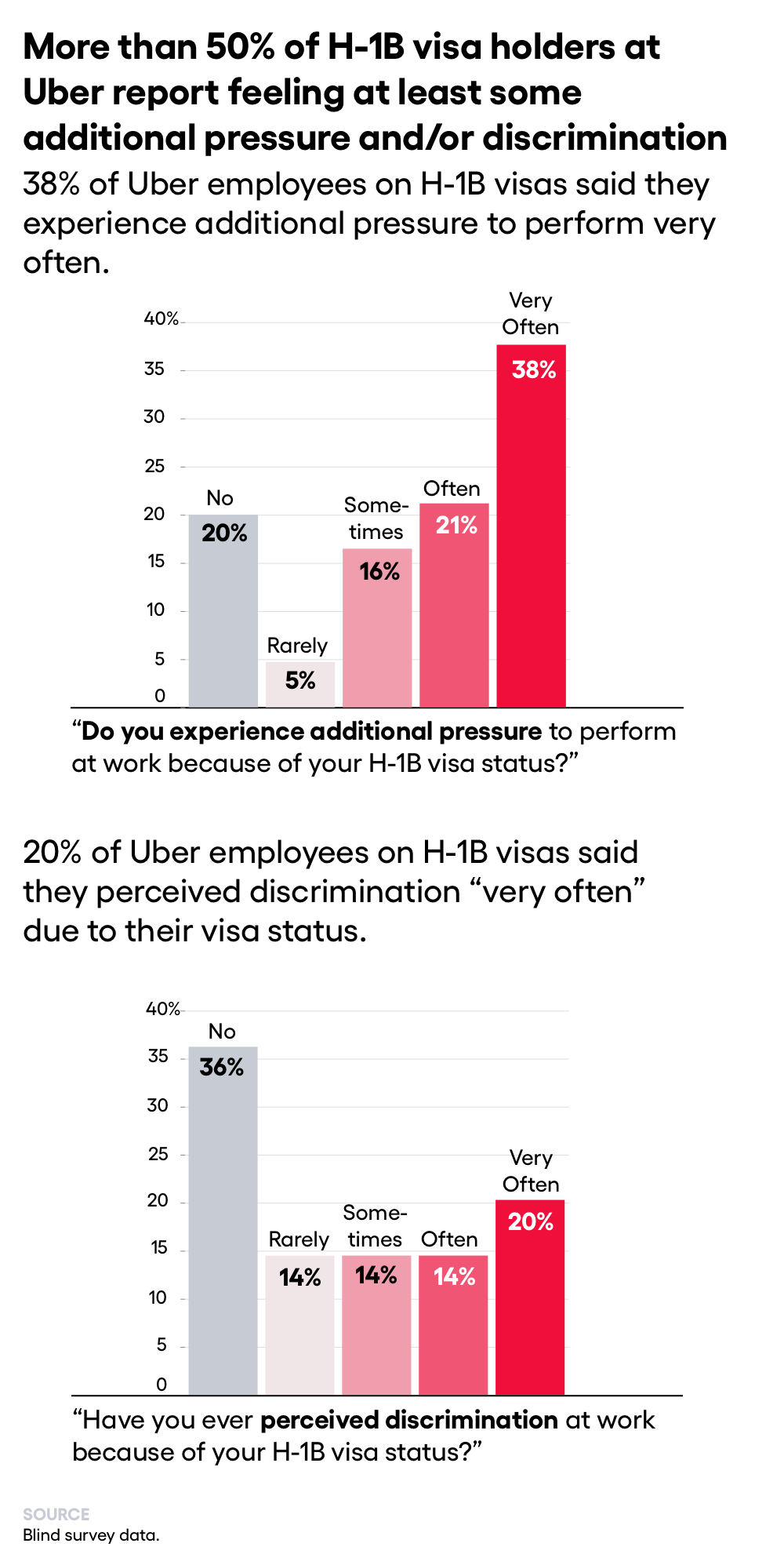

H-1B workers are hyper-aware of their temporary, employer-dependent livelihoods. OneZero asked Blind users on H-1B visas if they “experience additional pressure to perform at work” because of their status. Seventeen companies stood out for having a significant proportion — at least 50% — of employees responding “Very often” or “Often” to this question. They include Amazon, Facebook, WeWork, Uber, PayPal, eBay, Samsung, Cisco, Capital One, SAP, Symantec, Splunk, Goldman Sachs, Visa, VmWare, Intuit, and Deloitte.

Conversely, at Airbnb, Nvidia, Adobe, and LinkedIn, at least 50% of people responded “Rarely” and “No” to this question.

A burgeoning labor movement swept through Silicon Valley last year, led by employees, contractors, and gig workers. H-1B recipients were absent from this narrative. When visa access is controlled by an employer, even a single poor review can feel like an existential threat. OneZero was told by several H-1B employees that speaking out in the workplace is intimidating for visa holders, so many don’t.

“I believe that H-1B employees tend to tolerate more bullshit from managers because they cannot move to another company that easily, and they cannot just rage-quit,” said Alex. “This is possibly the key reason why managers like H-1Bs — lower turnover rate and employees who will take more shit.”

These employees “cannot afford to disagree with their managers,” said Chris, an H-1B visa holder and manager at Cognizant. “Most of the time there is a consequence for the worker.”

At Amazon, where hundreds of employees recently protested the company’s inaction on climate change, many H-1B workers reported extreme job pressures that could, in theory, deter them from participating in organizing efforts.

“There is always a feeling of, ‘I cannot speak up because that may lead to me losing my job and my right to live in this country,’” said Sam, who worked on an H-1B visa at several technology companies and is now employed by Slack. “I felt that pressure more at a smaller [startup] company like Bright and Flexport than at Facebook and Slack.” Smaller companies tend to have higher rates of friction because employees are taking on more responsibilities.

Workers on H-1B visas face unique forms of discrimination, though they may not be readily apparent. The industry’s affinity for these visas has undeniably hurt American workers laid off and supplanted by H-1B workers, but it has also pitted foreign and U.S. workforces against one another. Oracle, for example, was found guilty last year of showing preference for H-1B workers over Black and women employees.

The responses of H-1B workers to the OneZero survey and questionnaire suggest the issue of workplace discrimination is especially complex, and isn’t confined to racist behavior. “People in general tend to ignore our recommendations, and will later force us to clean up the mess, as that is really our job,” said Chris. “I have seen instances where mistakes done by full-time employees get ignored as ‘moments of learning,’ while if the same was done by a contractor [on an H-1B visa], it would turn out to be a job termination situation.”

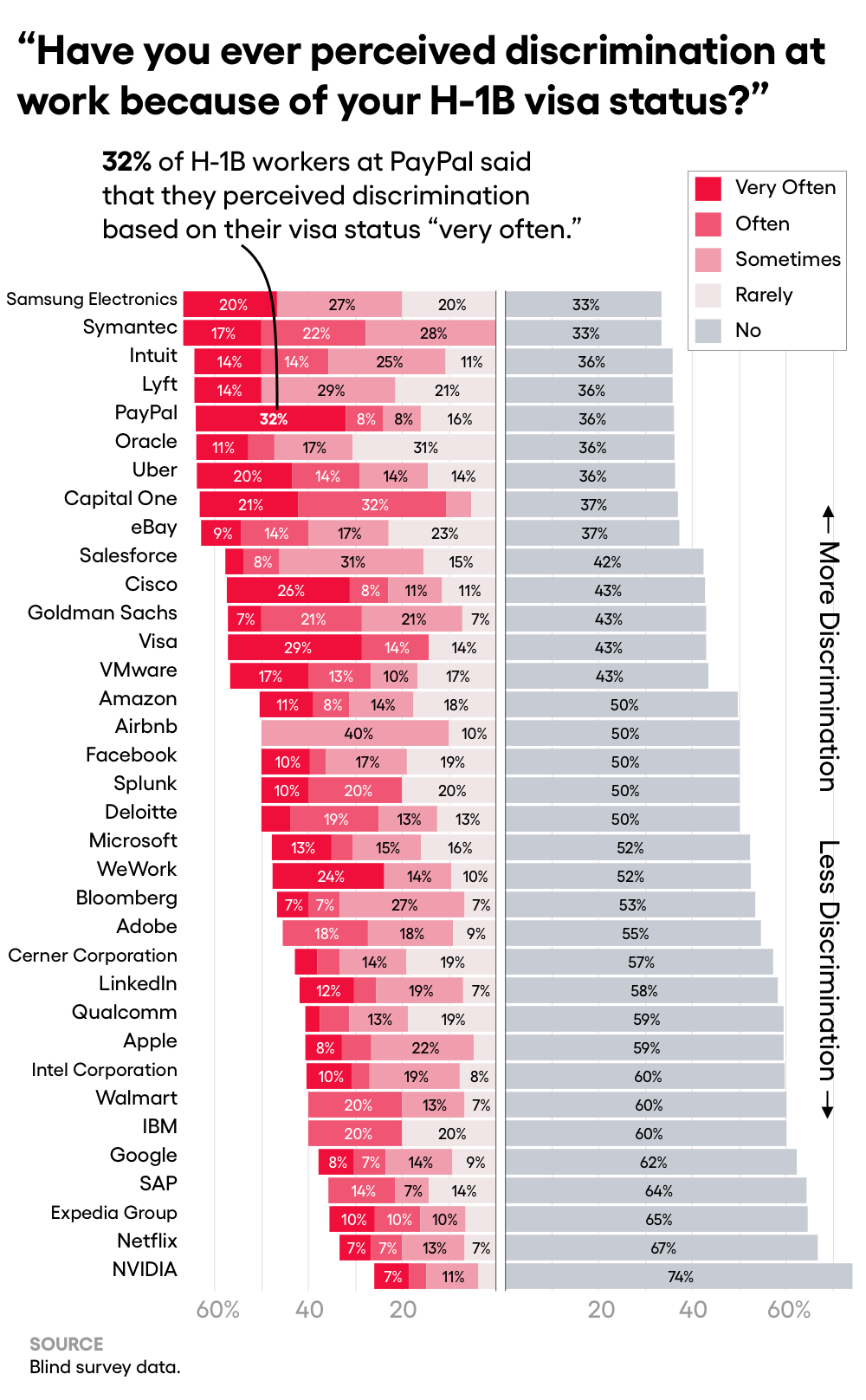

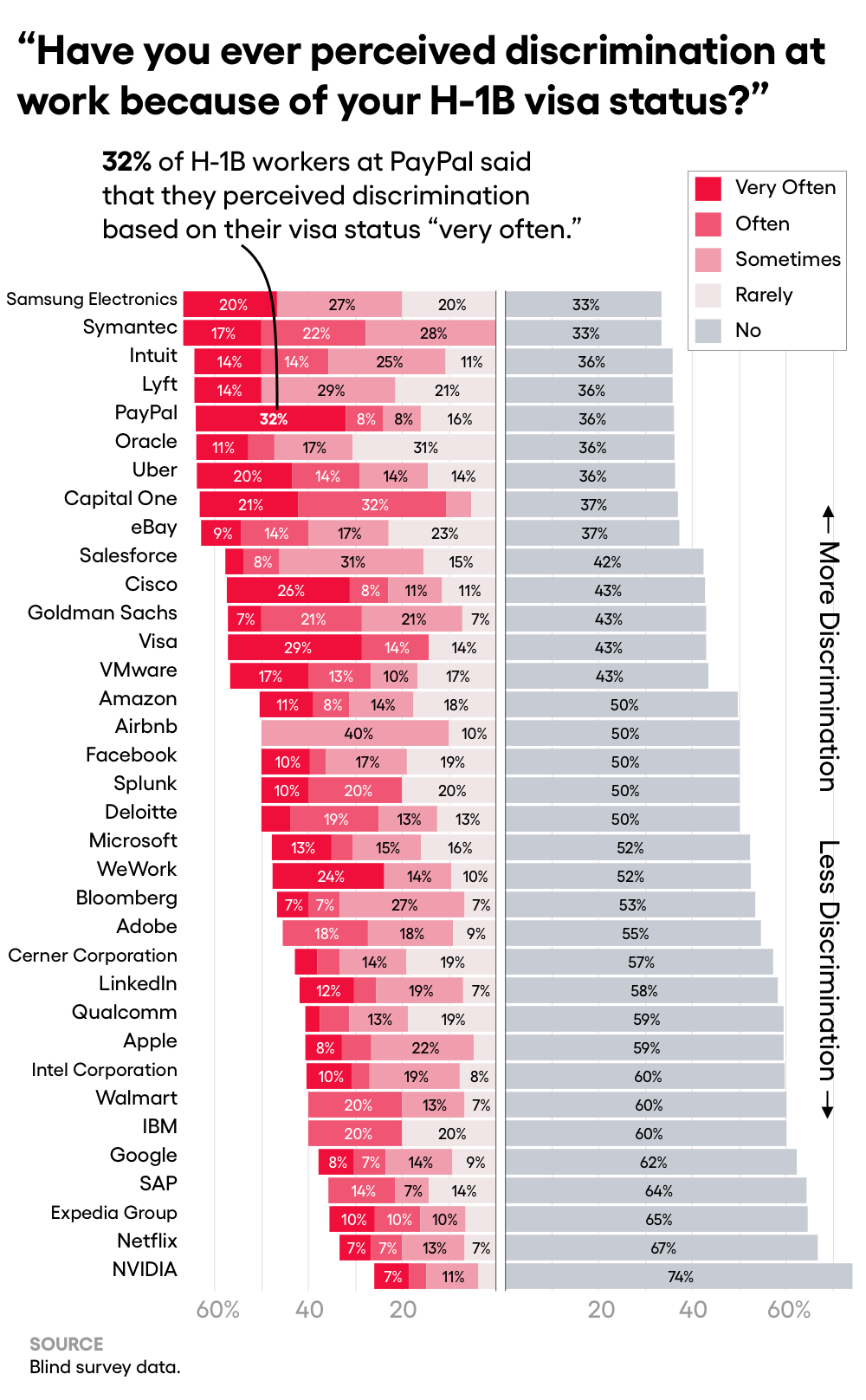

When OneZero asked Blind users if they have “ever perceived discrimination at work” because of their H-1B visa status, most participants said they had not. Of the 35 companies represented by the survey, only one, Capital One, had more than 50% of its respondents reply “Very often” or “Often” to the question. At Apple, Salesforce, Lyft, Airbnb, Samsung, Intuit, Bloomberg, Symantec, and Goldman Sachs, between 20% and 40% of respondents replied “Sometimes.” The poll didn’t specify forms of discrimination, but it can manifest as racism, pay inequality, and other prejudicial treatment.

At Uber, a company found guilty of gender discrimination by a federal probe last year, two-thirds of H-1B employees who responded to the survey said they had experienced some degree of workplace discrimination. That same year, Uber laid off nearly 400 employees as it ramped up H-1B hires.

Others indicated they hadn’t experienced any discrimination tied to their status. “I never felt discriminated against,” said Sam. “Facebook has a policy of giving out large signing bonuses of $100,000 for [H-1B recipients who graduate from American universities].”

Forty-two percent of participants said they believe they earn less than their coworkers because of their visa status.

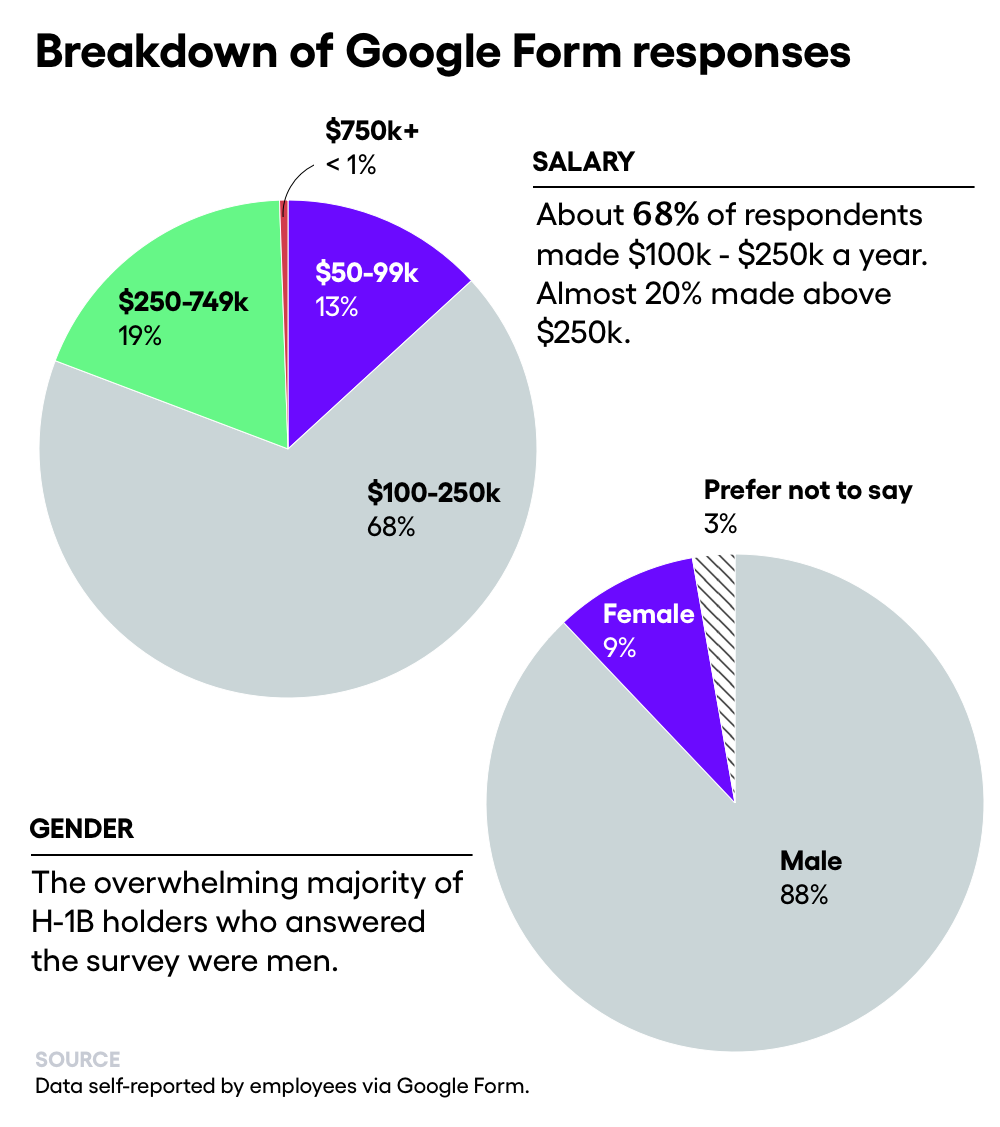

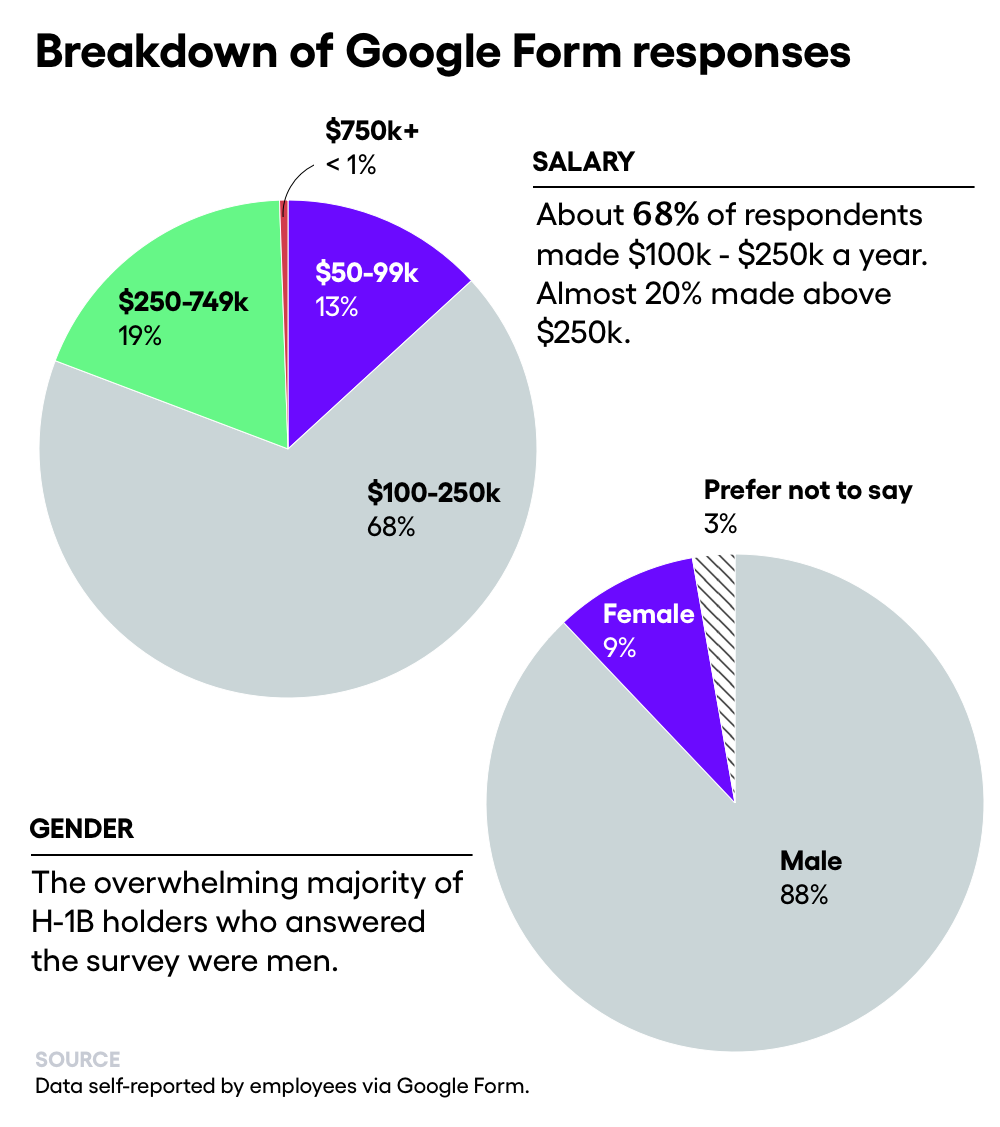

According to the questionnaire, 13% claimed an annual salary range of $50,000 to $99,999; 19% claimed $250,000 to $749,000; 68% claimed $100,000 to $249,999; and one person reported earning $750,000 or higher.

The Department of Labor states that employers must pay H-1B workers no less than the “prevailing wage” set for their role in their geographic area of employment. But the federal law still technically allows employers to misclassify H-1B recipients as entry-level employees, meaning they can be paid less. In Silicon Valley, entry-level computer programmers earn $52,229 while the average for American programmers is roughly $90,000.

“The most damaging discrimination comes from employers,” says Patricia Campos-Medina, an immigrant rights advocate and co-director of the New York State AFL-CIO/Cornell Union Leadership Institute. “Unless you’re able to disentangle the visa from the employer, you have to accept whatever working conditions they offer. Workers can file a complaint, but are they going to do it and lose their visa? Most of them have to accept lower salaries.”

H-1B workers are hyper-aware of their temporary, employer-dependent livelihoods. OneZero asked Blind users on H-1B visas if they “experience additional pressure to perform at work” because of their status. Seventeen companies stood out for having a significant proportion — at least 50% — of employees responding “Very often” or “Often” to this question. They include Amazon, Facebook, WeWork, Uber, PayPal, eBay, Samsung, Cisco, Capital One, SAP, Symantec, Splunk, Goldman Sachs, Visa, VmWare, Intuit, and Deloitte.

Conversely, at Airbnb, Nvidia, Adobe, and LinkedIn, at least 50% of people responded “Rarely” and “No” to this question.

A burgeoning labor movement swept through Silicon Valley last year, led by employees, contractors, and gig workers. H-1B recipients were absent from this narrative. When visa access is controlled by an employer, even a single poor review can feel like an existential threat. OneZero was told by several H-1B employees that speaking out in the workplace is intimidating for visa holders, so many don’t.

“I believe that H-1B employees tend to tolerate more bullshit from managers because they cannot move to another company that easily, and they cannot just rage-quit,” said Alex. “This is possibly the key reason why managers like H-1Bs — lower turnover rate and employees who will take more shit.”

These employees “cannot afford to disagree with their managers,” said Chris, an H-1B visa holder and manager at Cognizant. “Most of the time there is a consequence for the worker.”

At Amazon, where hundreds of employees recently protested the company’s inaction on climate change, many H-1B workers reported extreme job pressures that could, in theory, deter them from participating in organizing efforts.

“There is always a feeling of, ‘I cannot speak up because that may lead to me losing my job and my right to live in this country,’” said Sam, who worked on an H-1B visa at several technology companies and is now employed by Slack. “I felt that pressure more at a smaller [startup] company like Bright and Flexport than at Facebook and Slack.” Smaller companies tend to have higher rates of friction because employees are taking on more responsibilities.

Workers on H-1B visas face unique forms of discrimination, though they may not be readily apparent. The industry’s affinity for these visas has undeniably hurt American workers laid off and supplanted by H-1B workers, but it has also pitted foreign and U.S. workforces against one another. Oracle, for example, was found guilty last year of showing preference for H-1B workers over Black and women employees.

The responses of H-1B workers to the OneZero survey and questionnaire suggest the issue of workplace discrimination is especially complex, and isn’t confined to racist behavior. “People in general tend to ignore our recommendations, and will later force us to clean up the mess, as that is really our job,” said Chris. “I have seen instances where mistakes done by full-time employees get ignored as ‘moments of learning,’ while if the same was done by a contractor [on an H-1B visa], it would turn out to be a job termination situation.”

When OneZero asked Blind users if they have “ever perceived discrimination at work” because of their H-1B visa status, most participants said they had not. Of the 35 companies represented by the survey, only one, Capital One, had more than 50% of its respondents reply “Very often” or “Often” to the question. At Apple, Salesforce, Lyft, Airbnb, Samsung, Intuit, Bloomberg, Symantec, and Goldman Sachs, between 20% and 40% of respondents replied “Sometimes.” The poll didn’t specify forms of discrimination, but it can manifest as racism, pay inequality, and other prejudicial treatment.

At Uber, a company found guilty of gender discrimination by a federal probe last year, two-thirds of H-1B employees who responded to the survey said they had experienced some degree of workplace discrimination. That same year, Uber laid off nearly 400 employees as it ramped up H-1B hires.

Others indicated they hadn’t experienced any discrimination tied to their status. “I never felt discriminated against,” said Sam. “Facebook has a policy of giving out large signing bonuses of $100,000 for [H-1B recipients who graduate from American universities].”

Forty-two percent of participants said they believe they earn less than their coworkers because of their visa status.

According to the questionnaire, 13% claimed an annual salary range of $50,000 to $99,999; 19% claimed $250,000 to $749,000; 68% claimed $100,000 to $249,999; and one person reported earning $750,000 or higher.

The Department of Labor states that employers must pay H-1B workers no less than the “prevailing wage” set for their role in their geographic area of employment. But the federal law still technically allows employers to misclassify H-1B recipients as entry-level employees, meaning they can be paid less. In Silicon Valley, entry-level computer programmers earn $52,229 while the average for American programmers is roughly $90,000.

“The most damaging discrimination comes from employers,” says Patricia Campos-Medina, an immigrant rights advocate and co-director of the New York State AFL-CIO/Cornell Union Leadership Institute. “Unless you’re able to disentangle the visa from the employer, you have to accept whatever working conditions they offer. Workers can file a complaint, but are they going to do it and lose their visa? Most of them have to accept lower salaries.”

Recent political shifts in the United States, combined with the current administration’s openly hostile posture toward immigrants, has caused some H-1B applicants to think twice about life in America. Sixty-four percent of respondents to OneZero’s Google questionnaire said they do not support the Trump administration’s policies to aggressively deny H-1B applications. Nineteen percent said they do, and the rest were undecided.

“Many prospective H-1B employees actually cheered that Trump would get rid of consultants’ eligibility to apply for H-1Bs,” said Alex. Still, “extending an H-1B used to almost always be approved, now it’s being treated as a new application. Transferring an H-1B to another company now has rejection risks, or [can result in USCIS sending the applicant] a Request for Evidence, which can take months.”

“Politicians need to show something to their support groups, and companies try to avoid becoming a poster child for taking U.S. jobs,” said Chris.

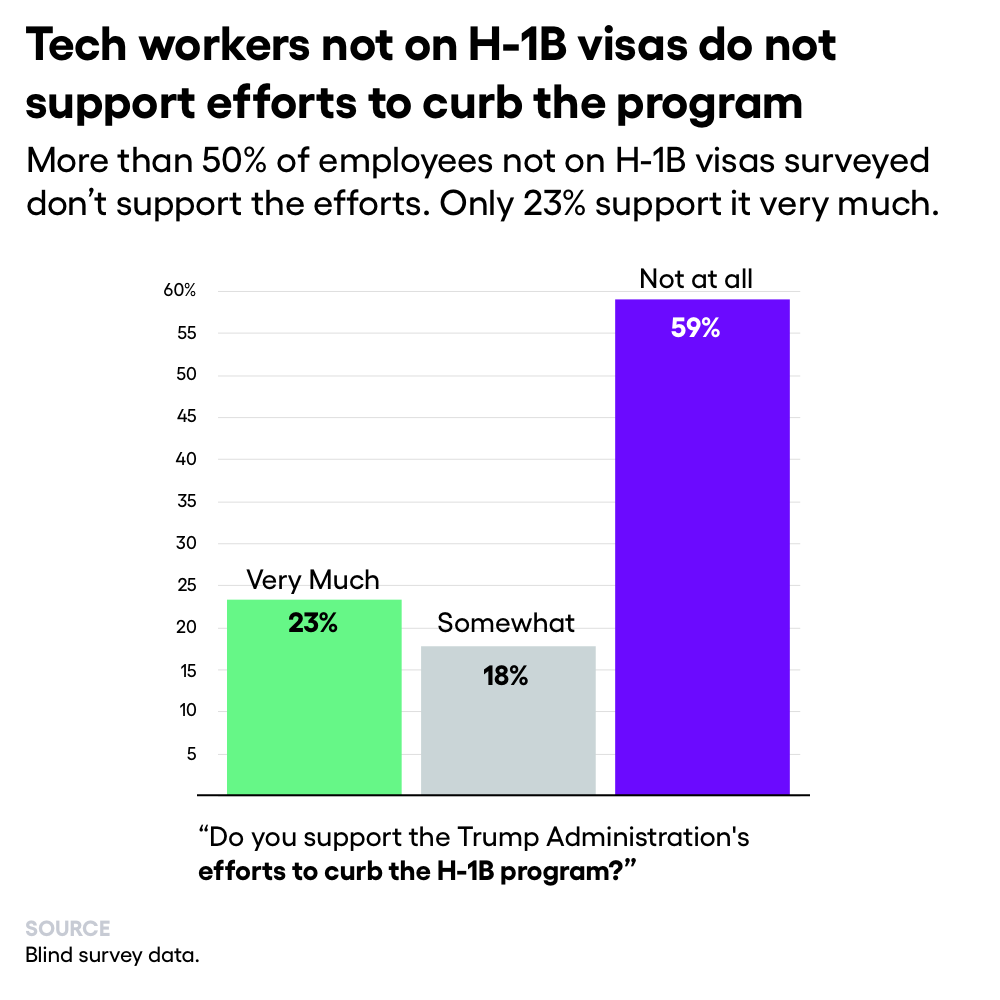

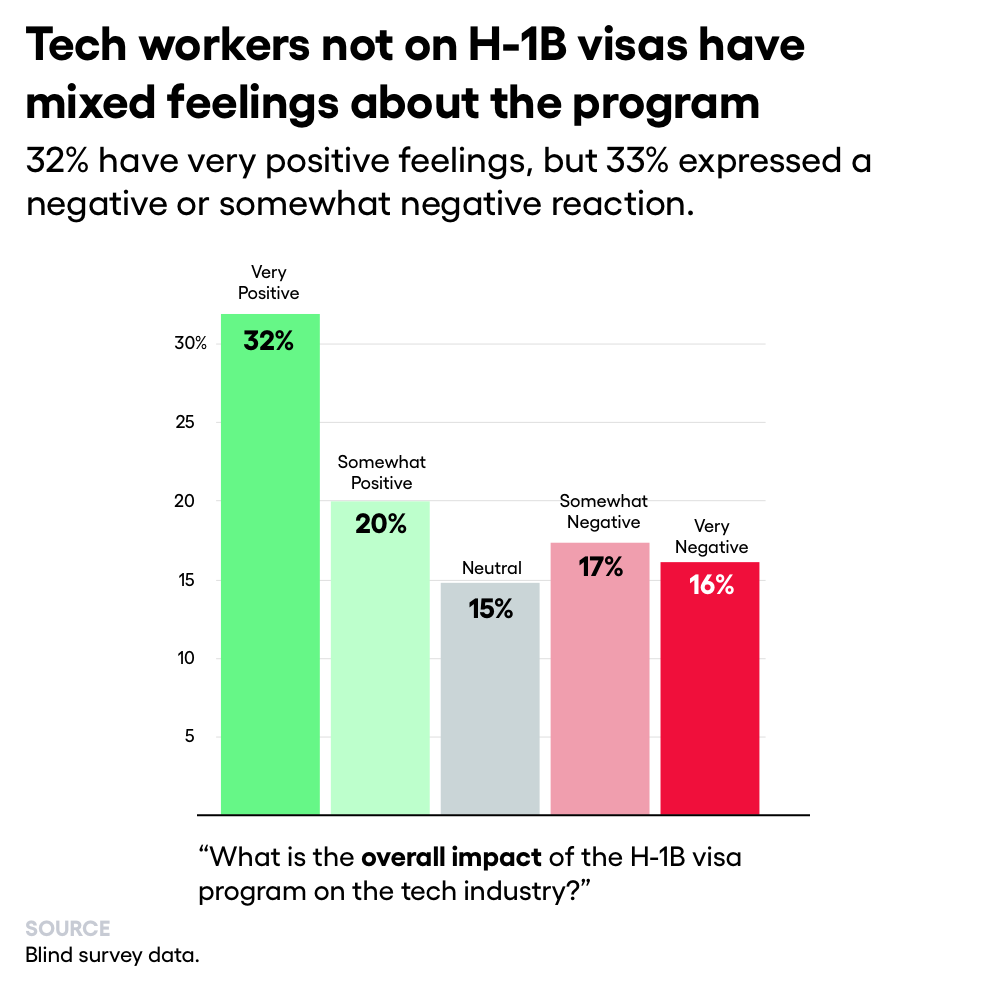

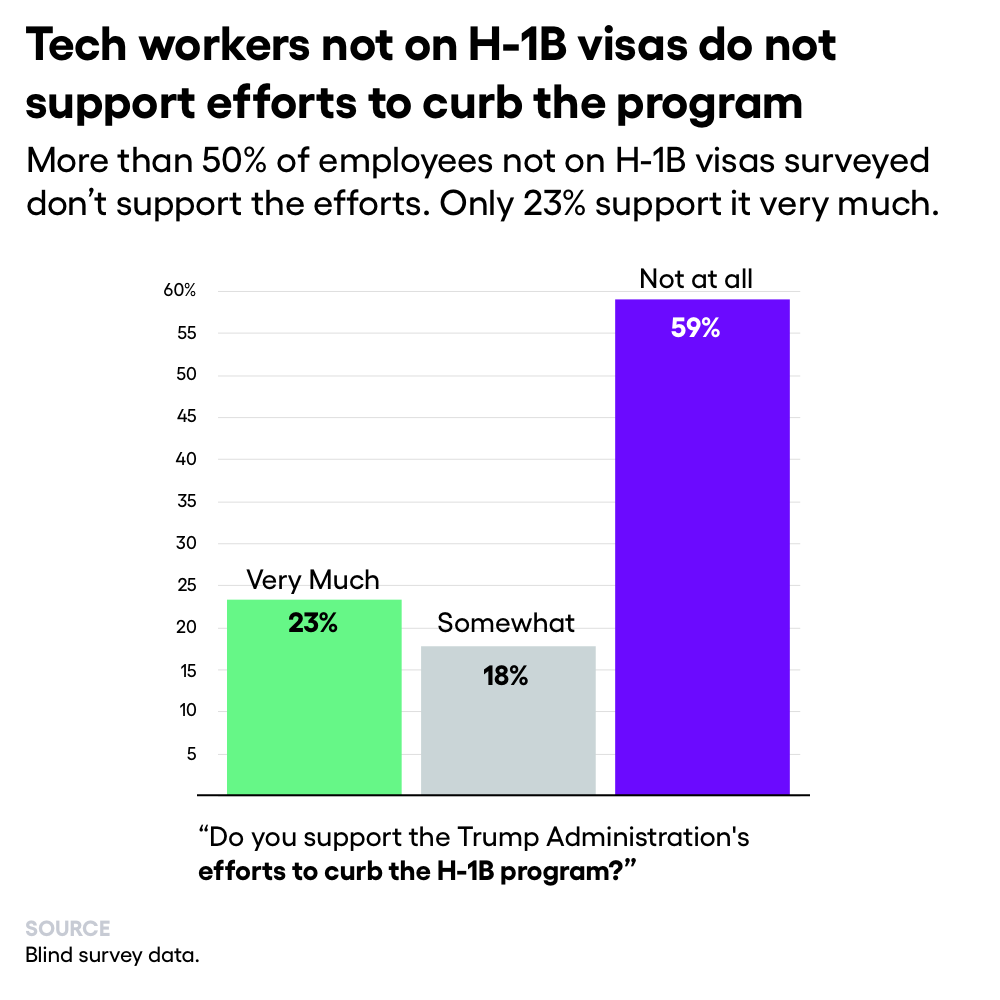

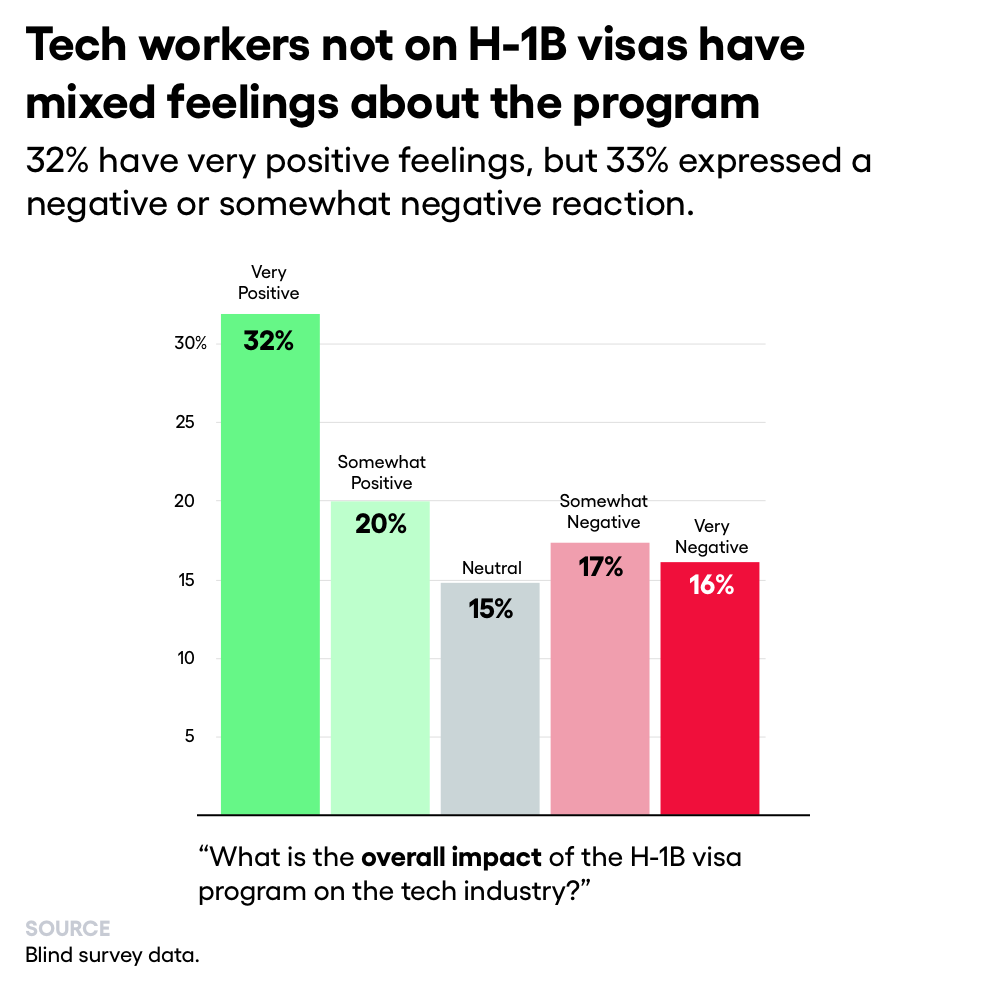

To get a sense of how technology workers not on H-1B visas regard coworkers who are, OneZero ran a second Blind poll in early 2020. The survey ran for 10 days and collected more than 2,600 responses from non-H-1B employees at 42 companies such as Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

Of these workers, nearly 60% oppose policies that would limit the visa program. All of this provides an alternate perspective to stories of friction between American and H-1B workers.

But companies like eBay stood out for having a large percentage of workers who expressed support for curbing the H-1B program. Forty-eight percent of respondents from eBay said they “Very much” support the Trump administration’s efforts to curb the H-1B program, while only 28% said they do not. In contrast, employees at Facebook, Lyft, and Uber overwhelmingly opposed efforts to curb the H-1B program. At Facebook, a largely liberal workplace, 69% of respondents said they do “not at all” support the current administration’s efforts to rein in H-1B visas, while just 16% said they do.

The survey also polled the sentiment of non-H-1B workers about the “overall impact of the H-1B program on the technology industry.” Half of respondents said that the program has a positive impact on the technology sector. A large proportion of workers at Facebook, Google, Nvidia, and Walmart say the program has been “Very positive.” Forty-three percent of workers at Google, another company known for progressive corporate values, responded this way, while only 13% say they feel the H-1B visa’s effect has been “Very negative.” At Amazon, which boasted one of the largest shares of new H-1B visas in 2017, 34% of respondents felt very positive about the program, while 22% felt its impact has been very negative.

“Many prospective H-1B employees actually cheered that Trump would get rid of consultants’ eligibility to apply for H-1Bs,” said Alex. Still, “extending an H-1B used to almost always be approved, now it’s being treated as a new application. Transferring an H-1B to another company now has rejection risks, or [can result in USCIS sending the applicant] a Request for Evidence, which can take months.”

“Politicians need to show something to their support groups, and companies try to avoid becoming a poster child for taking U.S. jobs,” said Chris.

To get a sense of how technology workers not on H-1B visas regard coworkers who are, OneZero ran a second Blind poll in early 2020. The survey ran for 10 days and collected more than 2,600 responses from non-H-1B employees at 42 companies such as Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

Of these workers, nearly 60% oppose policies that would limit the visa program. All of this provides an alternate perspective to stories of friction between American and H-1B workers.

But companies like eBay stood out for having a large percentage of workers who expressed support for curbing the H-1B program. Forty-eight percent of respondents from eBay said they “Very much” support the Trump administration’s efforts to curb the H-1B program, while only 28% said they do not. In contrast, employees at Facebook, Lyft, and Uber overwhelmingly opposed efforts to curb the H-1B program. At Facebook, a largely liberal workplace, 69% of respondents said they do “not at all” support the current administration’s efforts to rein in H-1B visas, while just 16% said they do.

The survey also polled the sentiment of non-H-1B workers about the “overall impact of the H-1B program on the technology industry.” Half of respondents said that the program has a positive impact on the technology sector. A large proportion of workers at Facebook, Google, Nvidia, and Walmart say the program has been “Very positive.” Forty-three percent of workers at Google, another company known for progressive corporate values, responded this way, while only 13% say they feel the H-1B visa’s effect has been “Very negative.” At Amazon, which boasted one of the largest shares of new H-1B visas in 2017, 34% of respondents felt very positive about the program, while 22% felt its impact has been very negative.

More than anything, OneZero’s findings underscore the complexities of the H-1B program, and a mixed sentiment for both workers on H-1B visas and those who work alongside them. Meanwhile, the program continues to come under fire from the Trump administration.

The White House’s “Buy American and Hire American” policy correlates to a record number of visa rejections. The denial rate for first-time H-1B applications jumped from 10% in 2016 to 24% in 2019, according to an investigation by Reveal and Mother Jones. The change has mostly impacted IT outsourcing firms; technology companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google saw some of the most H-1B visa approvals in 2017.

“Politicians need to show something to their support groups, and companies try to avoid becoming a poster child for taking U.S. jobs.”

Labor and immigrant rights advocates are calling for a federal overhaul of the H-1B system to make it more equitable. For example, when the number of H-1B applications exceed the amount of available visas — which has been the case for the last seven years — the process is left to a random lottery. But a rule that allocates visas based on higher wage levels can incentivize employers to pay their workers fairly. Democratic lawmakers have also introduced new legislation that would eliminate per-country caps on employment-based visas, something that, if passed, could drastically reduce the wait time for permanent residency. Right now, no more than 7% of green cards can be issued to citizens of any one country, meaning Indian H-1B workers, for instance, are disproportionately faced with decades — even centuries — long backlogs.

“What’s needed is to lift standards for all workers,” said Wasser. The narrative around H-1B holders is “often mischaracterized as pitting one worker against another, which is categorically wrong,” he added. “Programs need to be reformed since right now the system only benefits employers, not H-1B or U.S. workers.”

LINKED FROM https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/02/go-read-this-survey-about-tech-workers.html

The White House’s “Buy American and Hire American” policy correlates to a record number of visa rejections. The denial rate for first-time H-1B applications jumped from 10% in 2016 to 24% in 2019, according to an investigation by Reveal and Mother Jones. The change has mostly impacted IT outsourcing firms; technology companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google saw some of the most H-1B visa approvals in 2017.

“Politicians need to show something to their support groups, and companies try to avoid becoming a poster child for taking U.S. jobs.”

Labor and immigrant rights advocates are calling for a federal overhaul of the H-1B system to make it more equitable. For example, when the number of H-1B applications exceed the amount of available visas — which has been the case for the last seven years — the process is left to a random lottery. But a rule that allocates visas based on higher wage levels can incentivize employers to pay their workers fairly. Democratic lawmakers have also introduced new legislation that would eliminate per-country caps on employment-based visas, something that, if passed, could drastically reduce the wait time for permanent residency. Right now, no more than 7% of green cards can be issued to citizens of any one country, meaning Indian H-1B workers, for instance, are disproportionately faced with decades — even centuries — long backlogs.

“What’s needed is to lift standards for all workers,” said Wasser. The narrative around H-1B holders is “often mischaracterized as pitting one worker against another, which is categorically wrong,” he added. “Programs need to be reformed since right now the system only benefits employers, not H-1B or U.S. workers.”

LINKED FROM https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2020/02/go-read-this-survey-about-tech-workers.html

No comments:

Post a Comment