Move raises questions about status of Ainu ethnic minority, whose cultural identity Japan is legally obliged to protect

Justin McCurry in Tokyo Fri 21 Feb 2020

An Ainu ritual ceremony. An estimated 13,000

Ainu people live in Hokkaido, according to a 2017

survey, but the actual number is thought to

be much higher. Photograph: Kim Kyung-Hoon/Reuters

Japan’s commitment to the rights of its indigenous people has been questioned after organisers of this summer’s Tokyo Olympics dropped a performance by members of the Ainu ethnic minority from the Games’ opening ceremony.

Members of the Ainu community, originally from Japan’s northernmost island of Hokkaido, had been expecting to showcase their culture to the world in a dance at the Olympic stadium, but learned recently that the plans had been scrapped.

The Tokyo 2020 organising committee said the performance had been dropped from the ceremony due to “logistical constraints”.

Dream weavers: the indigenous Ainu people of Japan – in pictures

The Ainu of Hokkaido in Japan were not officially recognised as an indigenous people until 2008. This recognition came after a long history of exclusion and assimilation that almost erased their society, language and culture. Photographer Laura Liverani collaborated with members of the Ainu for this exhibition called Coexistences: Portraits of Today’s Japan

Magi is a transgender woman originally from Okinawa. Although not an Ainu by blood, Magi has embraced the indigenous way of life, after having lived as an Ainu in a commune in Nibutani for many years. She is skilled in traditional Ainu embroidery, which she incorporates in her handmade clothes.

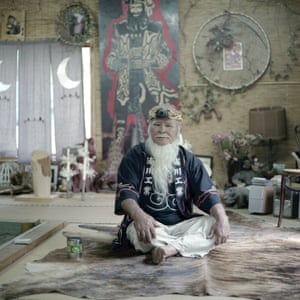

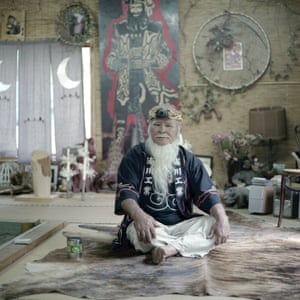

Ainu elder Haruzo Urakawa in his home. Kamuy Mintara, meaning ‘Playground of Gods’, is a Cise, a traditional Ainu home, that 75-year-old Haruzo Urakawa built by himself in the mountains outside of Tokyo. Here, he lived as closely as possible to the traditional Ainu lifestyle, which, as a child in Hokkaido, he had learned from his father.

“Unfortunately, this particular Ainu dance performance could not be included because of logistical constraints related to the ceremonies,” it said in a statement to the Guardian.

“However, Tokyo 2020 is still deliberating other ways to include the Ainu community. We are not able to provide further details of the content of the opening and closing ceremonies.”

The public broadcaster NHK said last week that an Ainu ceremonial dance would be included in a cultural exposition at the Tokyo National Museum in March, but Ainu representatives said performers, who had already started rehearsing, had been anticipating an appearance on a much bigger stage.

“Everyone was looking forward to performing at the Olympic stadium,” said Kazuaki Kaizawa of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, which started discussing the inclusion of an Ainu element in the opening ceremony with organisers three years ago.

“We are willing to talk to the organisers about how Ainu culture can be represented during the Olympics,” Kaizawa told the Guardian, adding that the Games’ organising committee had yet to explain its decision. “We’re hopeful something can be worked out.”

The decision sits uncomfortably with recent moves by Japan’s government to improve the status of the Ainu. In May last year, parliament passed a law that legally recognised them as Japan’s indigenous people, obliging the government to protect their cultural identity and ban discrimination in employment, education and other areas.

The law was intended to officially end more than a century of discrimination that began in the late 19th century, when Japan’s Meiji-era government took control of Hokkaido, where the Ainu had been hunting, fishing, practising an animist religion and speaking their own language since the 1300s, according to experts.

But after opening the island to Japanese settlers, the government forced the Ainu, who it referred to as “former aborigines”, to assimilate.

An estimated 13,000 Ainu currently live in Hokkaido, according to a 2017 survey, although the actual number is thought to be much higher, as many are reluctant to identify themselves as Ainu and have moved to other parts of Japan.

Members of the Ainu community continue to encounter prejudice. They are half as likely to attend university as other Japanese, according to official data, and Ainu households can expect to earn significantly less than the national average. In a 2017 survey, over 23% of Ainu people said they had been discriminated against.

“Society was not accepting of the Ainu, and it still isn’t,” said Mai Ishihara, an anthropologist at Hokkaido University. “There are still many people who keep their Ainu identity secret from their children.”

The lack of awareness of Japan’s indigenous people extends to the upper echelons of government. Last month, the finance minister, Taro Aso, drew condemnation after he claimed that Japan had been racially homogeneous for 2,000 years.

“There is no other nation but Japan where a single race has spoken a single language at a single location, and maintained a single dynasty with a single emperor for over 2,000 years,” Aso, who is also deputy prime minister, told constituency supporters. “It is a great nation.”

Aso later apologised. “If my remarks caused a misunderstanding, I apologise and will correct them,” he said.

Ainu representatives hope the opening in April of the National Ainu Museum and Park in Hokkaido, will lead to wider recognition of their history and traditions.

Known as Upopoy – or “singing together” in the Ainu language – the $220m (£171m) facility is part of a drive by the prime minister, Shinzo Abe, to draw more visitors to Sapporo, the biggest city in Hokkaido and now the venue for the Olympic marathons.

The events were controversially moved to Sapporo from Tokyo after the International Olympic Committee acted on warnings about the threat the capital’s searing heat and humidity posed to athletes and spectators.

“We hope people from around the world come to the park, but we also want to see lots of visitors from Japan,” Kaizawa said. “Too many Japanese are still unaware of our existence and our culture.”

Reuters contributed to this report

Japan’s commitment to the rights of its indigenous people has been questioned after organisers of this summer’s Tokyo Olympics dropped a performance by members of the Ainu ethnic minority from the Games’ opening ceremony.

Members of the Ainu community, originally from Japan’s northernmost island of Hokkaido, had been expecting to showcase their culture to the world in a dance at the Olympic stadium, but learned recently that the plans had been scrapped.

The Tokyo 2020 organising committee said the performance had been dropped from the ceremony due to “logistical constraints”.

Dream weavers: the indigenous Ainu people of Japan – in pictures

The Ainu of Hokkaido in Japan were not officially recognised as an indigenous people until 2008. This recognition came after a long history of exclusion and assimilation that almost erased their society, language and culture. Photographer Laura Liverani collaborated with members of the Ainu for this exhibition called Coexistences: Portraits of Today’s Japan

Magi is a transgender woman originally from Okinawa. Although not an Ainu by blood, Magi has embraced the indigenous way of life, after having lived as an Ainu in a commune in Nibutani for many years. She is skilled in traditional Ainu embroidery, which she incorporates in her handmade clothes.

Ainu elder Haruzo Urakawa in his home. Kamuy Mintara, meaning ‘Playground of Gods’, is a Cise, a traditional Ainu home, that 75-year-old Haruzo Urakawa built by himself in the mountains outside of Tokyo. Here, he lived as closely as possible to the traditional Ainu lifestyle, which, as a child in Hokkaido, he had learned from his father.

“Unfortunately, this particular Ainu dance performance could not be included because of logistical constraints related to the ceremonies,” it said in a statement to the Guardian.

“However, Tokyo 2020 is still deliberating other ways to include the Ainu community. We are not able to provide further details of the content of the opening and closing ceremonies.”

The public broadcaster NHK said last week that an Ainu ceremonial dance would be included in a cultural exposition at the Tokyo National Museum in March, but Ainu representatives said performers, who had already started rehearsing, had been anticipating an appearance on a much bigger stage.

“Everyone was looking forward to performing at the Olympic stadium,” said Kazuaki Kaizawa of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, which started discussing the inclusion of an Ainu element in the opening ceremony with organisers three years ago.

“We are willing to talk to the organisers about how Ainu culture can be represented during the Olympics,” Kaizawa told the Guardian, adding that the Games’ organising committee had yet to explain its decision. “We’re hopeful something can be worked out.”

The decision sits uncomfortably with recent moves by Japan’s government to improve the status of the Ainu. In May last year, parliament passed a law that legally recognised them as Japan’s indigenous people, obliging the government to protect their cultural identity and ban discrimination in employment, education and other areas.

The law was intended to officially end more than a century of discrimination that began in the late 19th century, when Japan’s Meiji-era government took control of Hokkaido, where the Ainu had been hunting, fishing, practising an animist religion and speaking their own language since the 1300s, according to experts.

But after opening the island to Japanese settlers, the government forced the Ainu, who it referred to as “former aborigines”, to assimilate.

An estimated 13,000 Ainu currently live in Hokkaido, according to a 2017 survey, although the actual number is thought to be much higher, as many are reluctant to identify themselves as Ainu and have moved to other parts of Japan.

Members of the Ainu community continue to encounter prejudice. They are half as likely to attend university as other Japanese, according to official data, and Ainu households can expect to earn significantly less than the national average. In a 2017 survey, over 23% of Ainu people said they had been discriminated against.

“Society was not accepting of the Ainu, and it still isn’t,” said Mai Ishihara, an anthropologist at Hokkaido University. “There are still many people who keep their Ainu identity secret from their children.”

The lack of awareness of Japan’s indigenous people extends to the upper echelons of government. Last month, the finance minister, Taro Aso, drew condemnation after he claimed that Japan had been racially homogeneous for 2,000 years.

“There is no other nation but Japan where a single race has spoken a single language at a single location, and maintained a single dynasty with a single emperor for over 2,000 years,” Aso, who is also deputy prime minister, told constituency supporters. “It is a great nation.”

Aso later apologised. “If my remarks caused a misunderstanding, I apologise and will correct them,” he said.

Ainu representatives hope the opening in April of the National Ainu Museum and Park in Hokkaido, will lead to wider recognition of their history and traditions.

Known as Upopoy – or “singing together” in the Ainu language – the $220m (£171m) facility is part of a drive by the prime minister, Shinzo Abe, to draw more visitors to Sapporo, the biggest city in Hokkaido and now the venue for the Olympic marathons.

The events were controversially moved to Sapporo from Tokyo after the International Olympic Committee acted on warnings about the threat the capital’s searing heat and humidity posed to athletes and spectators.

“We hope people from around the world come to the park, but we also want to see lots of visitors from Japan,” Kaizawa said. “Too many Japanese are still unaware of our existence and our culture.”

Reuters contributed to this report

No comments:

Post a Comment