Library

'Pyke notte thy nostrellys': 15th-century guide on children's manners digitised for first time

New British Library site ranges from medieval book Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke to manuscripts by Lewis Carroll and Jacqueline Wilson

Alison Flood Fri 21 Feb 2020

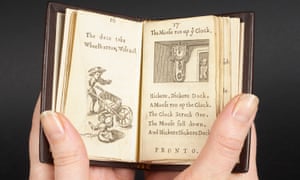

‘Some of these sources may seem uncannily familiar’ … a librarian opens Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (1744). Photograph: British Library Board

From Horrid Henry to Just William, naughty children are not difficult to find in children’s books today. But bad behaviour isn’t confined to recent decades – a manuscript from 1480, which has been digitised for the first time by the British Library, gives an insight into the antics of medieval children, as it exhorts them to “pyke notte thyne errys nothyr thy nostrellys” – don’t pick your ears or your nostrils - and to “spette not ovyr thy tabylle”.

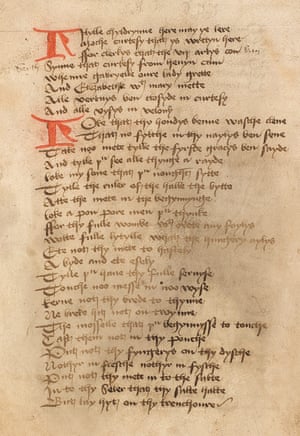

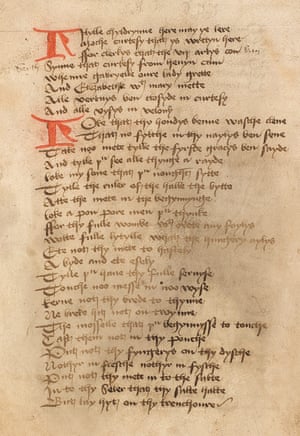

Don’t burp as if you had a bean in your throat’ … The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke, a medieval conduct book 15th century credit British Library Board Photograph: The British Library Board

The 15th-century conduct book, The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke, was intended to teach table manners. It has been put online as part of a new children’s literature website bringing together original manuscripts, interviews and drafts by authors from Lewis Carroll to Jacqueline Wilson. The medieval text is part of the British Library’s own collection, and “by listing all the many things that medieval children should not do, it also gives us a hint of the mischief they got up to”, said the library.

“Bulle not as a bene were in thi throote,” is another piece of advice doled out by the book – or “don’t burp as if you had a bean in your throat”. “And chesse cum by fore the, be not to redy,” children are warned – or “don’t be greedy when they bring out the cheese”. And long predating the Victorian age’s exhortations for children to be seen but not heard: “‘Loke thou laughe not, nor grenne / And with moche speche thou mayste do synne.” Or: “Don’t laugh, grin or talk too much.”

Anna Lobbenberg, the lead producer on the British Library’s digital learning programme, said: “These older collection items allow young people to examine the past close up. Some of these sources will seem fascinatingly remote, while others may seem uncannily familiar despite being created hundreds of years ago.”

More than 100 “treasures from children’s literature” feature on the new site, Discovering Children’s Books, including pages from Judith Kerr’s sketchbook for The Tiger Who Came to Tea, showing tigers drawn from life at London zoo. Axel Scheffler has shared the changing face of the Gruffalo, after he was told to make it less scary. There is also the first manuscript of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which would become Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Enid Blyton’s typescript drafts of The Famous Five and Last Term at Malory Towers.

From Horrid Henry to Just William, naughty children are not difficult to find in children’s books today. But bad behaviour isn’t confined to recent decades – a manuscript from 1480, which has been digitised for the first time by the British Library, gives an insight into the antics of medieval children, as it exhorts them to “pyke notte thyne errys nothyr thy nostrellys” – don’t pick your ears or your nostrils - and to “spette not ovyr thy tabylle”.

Don’t burp as if you had a bean in your throat’ … The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke, a medieval conduct book 15th century credit British Library Board Photograph: The British Library Board

The 15th-century conduct book, The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke, was intended to teach table manners. It has been put online as part of a new children’s literature website bringing together original manuscripts, interviews and drafts by authors from Lewis Carroll to Jacqueline Wilson. The medieval text is part of the British Library’s own collection, and “by listing all the many things that medieval children should not do, it also gives us a hint of the mischief they got up to”, said the library.

“Bulle not as a bene were in thi throote,” is another piece of advice doled out by the book – or “don’t burp as if you had a bean in your throat”. “And chesse cum by fore the, be not to redy,” children are warned – or “don’t be greedy when they bring out the cheese”. And long predating the Victorian age’s exhortations for children to be seen but not heard: “‘Loke thou laughe not, nor grenne / And with moche speche thou mayste do synne.” Or: “Don’t laugh, grin or talk too much.”

Anna Lobbenberg, the lead producer on the British Library’s digital learning programme, said: “These older collection items allow young people to examine the past close up. Some of these sources will seem fascinatingly remote, while others may seem uncannily familiar despite being created hundreds of years ago.”

More than 100 “treasures from children’s literature” feature on the new site, Discovering Children’s Books, including pages from Judith Kerr’s sketchbook for The Tiger Who Came to Tea, showing tigers drawn from life at London zoo. Axel Scheffler has shared the changing face of the Gruffalo, after he was told to make it less scary. There is also the first manuscript of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which would become Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Enid Blyton’s typescript drafts of The Famous Five and Last Term at Malory Towers.

Lightening the dark wood … Axel Scheffler sketching the Gruffalo. Photograph: Joe Turp

The site, bringing together collections from the British Library, Seven Stories, Bodleian Libraries and the V&A, will also feature Curiosities in the Tower of London, a miniature book published in 1741 by Thomas Boreman, the first publisher and bookseller to specialise in books for children. Describing the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London, the miniature book sees Boreman introduce the zoo’s lionesses, Jenny and Phillis, and the lion Marco with his “frightful teeth”. It will also show children the only book about suffragettes written for children during the Votes for Women campaign, Votes for Catherine Susan and Me by Kathleen Ainslie. Catherine Susan, and Me, are two peg dolls, who join the campaign, fighting policemen, smashing windows, going to prison and going on hunger strike. Perhaps unsurprisingly for the time, the tale was meant to be a cautionary one: “We cheered up when the Home Secretary and the Governor came to see us. And when they said ‘Will you go home quietly’? we said ‘YES’.”

No comments:

Post a Comment