Restoring longleaf pines, keystone of once vast ecosystems

by Janet McConnaughey

DECEMBER 30, 2020

This photo provided by The Nature Conservancy shows a prescribed fire sweeping through longleaf pines in 2019 at The Nature Conservancy's Calloway Preserve near Fort Bragg, N.C. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (Margaret Fields/The Nature Conservancy via AP)

When European settlers came to North America, fire-dependent savannas anchored by lofty pines with footlong needles covered much of what became the southern United States.

Yet by the 1990s, logging and clear-cutting for farms and development had all but eliminated longleaf pines and the grasslands beneath where hundreds of plant and animal species flourished.

Now, thanks to a pair of modern day Johnny Appleseeds, landowners, government agencies and nonprofits are working in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas to bring back pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets.

Longleaf pines now cover as much as 7,300 square miles (19,000 square kilometers)—and more than one-quarter of that has been planted since 2010.

"I like to say we rescued longleaf from the dustbin. I don't think we had any idea how successful we'd be," said Rhett Johnson, who founded gopher tortoise whose burrows shelter scores of animal species including mice, foxes, rabbits, snakes, even birds, and hundreds of kinds of insects.

Plants and animals have lost ground along with the longleaf. Nearly 30 are endangered or threatened. Dozens more are being studied to decide whether they should be protected.

When European settlers came to North America, fire-dependent savannas anchored by lofty pines with footlong needles covered much of what became the southern United States.

Yet by the 1990s, logging and clear-cutting for farms and development had all but eliminated longleaf pines and the grasslands beneath where hundreds of plant and animal species flourished.

Now, thanks to a pair of modern day Johnny Appleseeds, landowners, government agencies and nonprofits are working in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas to bring back pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets.

Longleaf pines now cover as much as 7,300 square miles (19,000 square kilometers)—and more than one-quarter of that has been planted since 2010.

"I like to say we rescued longleaf from the dustbin. I don't think we had any idea how successful we'd be," said Rhett Johnson, who founded gopher tortoise whose burrows shelter scores of animal species including mice, foxes, rabbits, snakes, even birds, and hundreds of kinds of insects.

Plants and animals have lost ground along with the longleaf. Nearly 30 are endangered or threatened. Dozens more are being studied to decide whether they should be protected.

A fire-charred longleaf pine stands in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is working to bring back the pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

Johnson, who retired in 2006 as director of Auburn's Solon Dixon Forestry Education Center in south Alabama, said working surrounded by longleaf made him realize that stands were losing quality and shrinking in range. "Just as alarming, people who understood longleaf were disappearing as well," he said.

Johnson and alliance cofounder Dean Gjerstad spread the word about the tree's importance. "We were like Johnny Appleseed—we were on the road all the time," said Johnson, who retired from the alliance in 2012.

By 2005, the alliance, government agencies, nonprofits, universities and private partners were working together. In 2010, they launched America's Longleaf Restoration Initiative, with a goal of having 12,500 square miles (32,370 square kilometers) of longleaf by 2025.

The initiative built on efforts by federal and state agencies including the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Resources Conservation Service to provide incentives for owners to return land to longleaf pines, Johnson said.

Johnson, who retired in 2006 as director of Auburn's Solon Dixon Forestry Education Center in south Alabama, said working surrounded by longleaf made him realize that stands were losing quality and shrinking in range. "Just as alarming, people who understood longleaf were disappearing as well," he said.

Johnson and alliance cofounder Dean Gjerstad spread the word about the tree's importance. "We were like Johnny Appleseed—we were on the road all the time," said Johnson, who retired from the alliance in 2012.

By 2005, the alliance, government agencies, nonprofits, universities and private partners were working together. In 2010, they launched America's Longleaf Restoration Initiative, with a goal of having 12,500 square miles (32,370 square kilometers) of longleaf by 2025.

The initiative built on efforts by federal and state agencies including the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Resources Conservation Service to provide incentives for owners to return land to longleaf pines, Johnson said.

Longleaf pines, about 80 to 85 years old, stand tall in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss., on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is working to bring back the pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

Most of the land planted in the last 10 years had been "highly erodible cropland," he said. "Better a longleaf plantation than a cotton field."

The initiative is trying to ensure that at least half the restored land is close enough to existing forests that plants and animals could, over generations, turn the new stands into functioning ecosystems.

When the ecosystem returns, landowners can look forward to annual income from activities such as hunting and wildlife photography rather than only from intermittent timber harvests, said Kevin Norton, acting chief of the National Resources Conservation Service.

Because most longleaf acreage is privately owned, 80% to 85% of the planting so far has been on private land, said Carol Denhof, president of The Longleaf Alliance.

Another 5,160 square miles (13,360 square kilometers) must be planted or reclaimed from stands overly mixed with other tree species to meet the initiative's 2025 deadline, she said. "I'm hopeful we can get there but ... we have a lot of work to do."

Most of the land planted in the last 10 years had been "highly erodible cropland," he said. "Better a longleaf plantation than a cotton field."

The initiative is trying to ensure that at least half the restored land is close enough to existing forests that plants and animals could, over generations, turn the new stands into functioning ecosystems.

When the ecosystem returns, landowners can look forward to annual income from activities such as hunting and wildlife photography rather than only from intermittent timber harvests, said Kevin Norton, acting chief of the National Resources Conservation Service.

Because most longleaf acreage is privately owned, 80% to 85% of the planting so far has been on private land, said Carol Denhof, president of The Longleaf Alliance.

Another 5,160 square miles (13,360 square kilometers) must be planted or reclaimed from stands overly mixed with other tree species to meet the initiative's 2025 deadline, she said. "I'm hopeful we can get there but ... we have a lot of work to do."

Silviculturist Keith Coursey walks between a 2-year-old longleaf pine "grass stage" seedling and a stand of 80- to 85-foot-tall longleaf pines in the DeSoto National Forest on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

Footlong needles that give longleaf pine its name are seen in the DeSoto National Forest on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020. An intensive effort in nine coastal states is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

This photo taken July 8, 2010, shows a baby Louisiana pine snake poking its head through the shell of its egg while hatching, which can take up to 24 hours, at The Memphis Zoo. Pine snakes are among nearly 30 plant and animal species that have become threatened or endangered as longleaf pines lost ground. (Jim Weber/The Commercial Appeal via AP, File)

A 2-year-old "grass stage" longleaf pine seedling stands in the DeSoto National Forest on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020, with U.S. Forest Service silviculturist Keith Coursey and some 80- to 85-year-old trees in the background. Longleaf forests once covered an estimated 92 million acres, a figure which had fallen to 3.4 million by 2010. Since then, people in nine coastal states from Texas to Virginia have added 1.3 million acres—some by planting seedlings, others by taking out shrubs and other trees in mixed forests. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

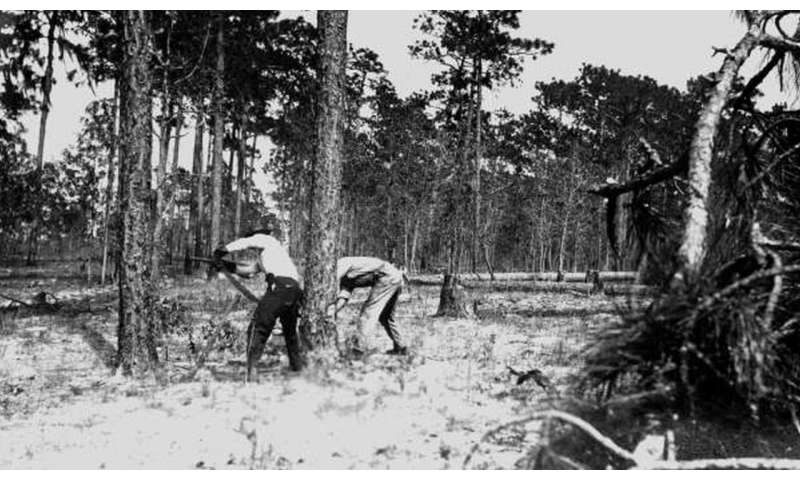

This photo from Florida's State Archives, taken near Mount Pleasant, Florida, on Aug. 7, 1936, shows two men in front of a stand of virgin longleaf pine before it was logged. When European settlers came to North America, fire-dependent savannas anchored by lofty pines with footlong needles covered much of what became the southern United States. Yet by the 1990s, logging, clear-cutting for farms and development and fire suppression had all but eliminated longleaf pines and the grasslands beneath where hundreds of plant and animal species flourished. Now an intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back the pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets. (Florida Forest Service/Florida's State Archives via AP)

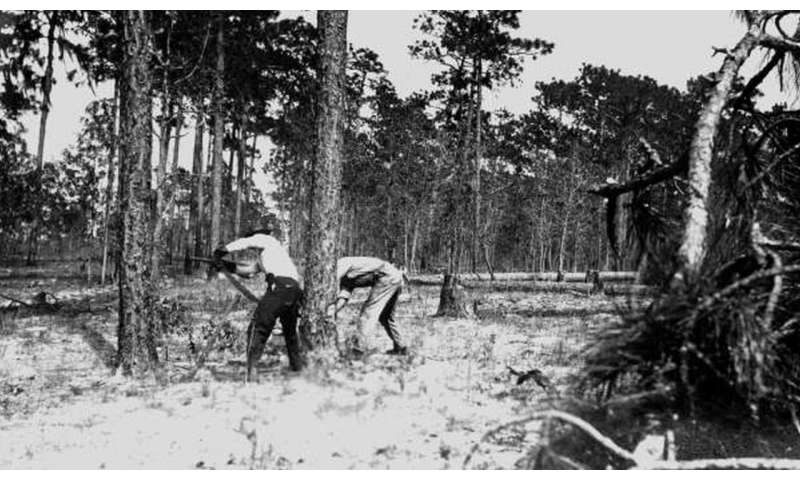

This photo, from Florida's State Archives, shows loggers felling a longleaf pine at De Leon Springs in April 1915. When European settlers came to North America, fire-dependent savannas anchored by lofty pines with footlong needles covered much of what became the southern United States. Yet by the 1990s, logging, clear-cutting for farms and development and fire suppression had all but eliminated longleaf pines and the grasslands beneath where hundreds of plant and animal species flourished. Now an intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back the pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets. (Florida's State Archives via AP)

In this photograph, from the State Archives of Florida, loggers use a team of oxen to haul away longleaf pine logs near Mount Pleasant, Fla., on Aug. 7, 1936. When European settlers came to North America, fire-dependent savannas anchored by lofty pines with footlong needles covered much of what became the southern United States. Yet by the 1990s, logging, clear-cutting for farms and development and fire suppression had all but eliminated longleaf pines and the grasslands beneath where hundreds of plant and animal species flourished. Now an intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back the pines named for the long needles prized by Native Americans for weaving baskets. (Florida Forest Service/State Archives of Florida via AP)

Charred bark on a 20-year-old, 8-inch diameter longleaf pine in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss., on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020, shows where a fire swept by, protecting grasses and wildflowers that otherwise would be robbed of sunlight by shrubs and shorter trees. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

Tiny carnivorous plants called sundews, like the fingertip-sized one shown here in the DeSoto National Forest, in Miss., on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020, are part of the wildly diverse longleaf pine ecosystem. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from from Virginia to Texas is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

Longleaf pine needles and a chunk of bark frame tiny carnivorous plants called sundews in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss., on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

Silviciulturist Keith Coursey stands in a thicket of gallberries—one of the shrubs that would block the sun from grasses and wildflowers in longleaf pine forests without regular fires—in front of a stand of 80- to 85-foot-tall longleaf pines in the DeSoto National Forest on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2020. An intensive effort in nine coastal states from Virginia to Texas is bringing back longleaf pines—armor-plated trees that bear footlong needles and need regular fires to spark their seedlings' growth and to support wildly diverse grasslands that include carnivorous plants and harbor burrowing tortoises. (AP Photo/Janet

About 400 acres (160 hectares) of land returned to longleaf were planted by the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, for their needles.

About 400 acres (160 hectares) of land returned to longleaf were planted by the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, for their needles. But branches from most of the first planting are now too high to reach. So Gesse Bullock, the tribe's fire management specialist, said he is pushing for another planting on the 10,200-acre (4,100-hectare) reservation.

Basket weavers include the tribe's realty officer, Elliott Abbey. "When I was younger," he said, "I thought it was work—something my aunts made me do,"

Now, Abbey said, "It strikes me in the heart that this could die out."

Explore further

About 400 acres (160 hectares) of land returned to longleaf were planted by the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, for their needles.

About 400 acres (160 hectares) of land returned to longleaf were planted by the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, for their needles. But branches from most of the first planting are now too high to reach. So Gesse Bullock, the tribe's fire management specialist, said he is pushing for another planting on the 10,200-acre (4,100-hectare) reservation.

Basket weavers include the tribe's realty officer, Elliott Abbey. "When I was younger," he said, "I thought it was work—something my aunts made me do,"

Now, Abbey said, "It strikes me in the heart that this could die out."

Explore further

Landscape-level habitat connectivity is key for species that depend on longleaf pine

© 2020 The Associated Press.

© 2020 The Associated Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment