Bloomberg News | October 28, 2023 |

Spirit Energy’s North and South Morecambe gas fields. (Image by Centrica Plc).

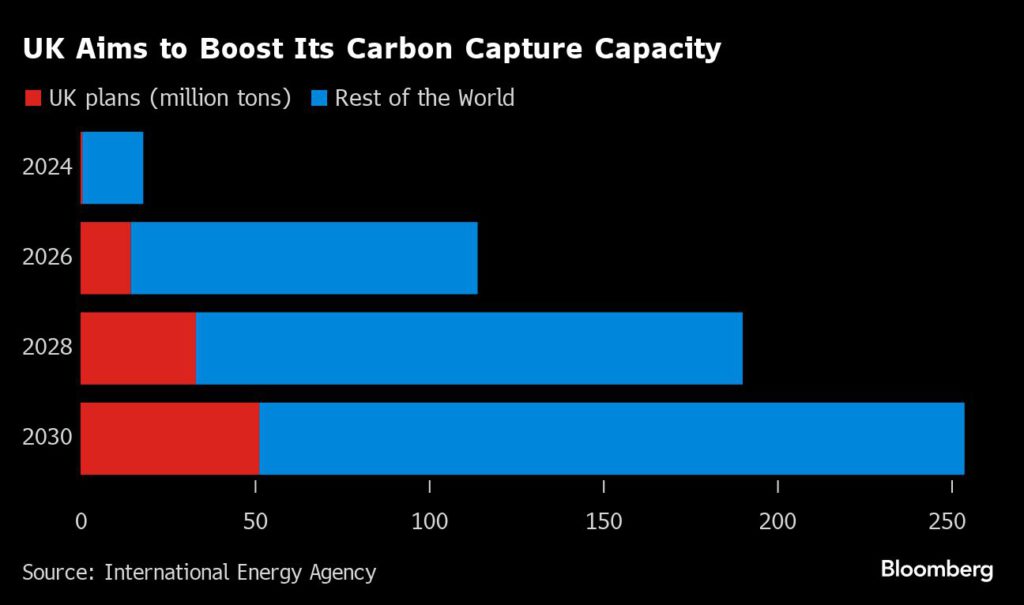

Centrica Plc boss Chris O’Shea is on a mission to show the UK government that it needs to rapidly speed up carbon capture projects, which could become crucial if the country is to reach its net zero ambitions.

The company’s aging Morecambe gas site, off the west coast of England, wasn’t selected for a support scheme this summer that’s backed by billions of pounds of government funding. Even after that disappointment, the energy business still plans to start burying carbon emissions from its own gas processing site nearby around early 2025.

The idea is to prove viability and then fully commercialize the operation, selling the carbon storage service to other industries. That will require about £1 billion ($1.2 billion) of investment, as well as government backing which O’Shea says isn’t moving fast enough.

Carbon capture and storage, or CCS, involves taking CO2 emissions, transporting them to a site — usually an old oil and gas field — and burying them.

It’s controversial, with critics saying it can help to extend the life of fossil fuels that should be winding down faster. It’s also expensive, and there’s a risk of environmental damage from leakage at storage sites.

But CCS remains in focus as a decarbonization tool because of slow global progress in reducing emissions. In the UK, worries about energy security and fuel prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government to issue new permits for oil and gas production in the North Sea. Other policy shifts have also raised questions about the UK’s ability to meet green targets, particularly its 2050 net zero goal.

Centrica’s CCS plans are centered on Morecambe in the Irish Sea, operated by joint venture Spirit Energy. Over the past four decades, Spirit Energy says the field has pumped out enough gas — more than 6.5 trillion cubic feet — to fill Scotland’s famous Loch Ness 25 times over.

Centrica currently expects to continue production until the end of the decade, having previous planned to stop in the mid-2020s.

The platforms there — mazes of pipes, bridges and rigging dotted with workers in bright orange overalls — are inextricably linked to the era of dirty energy that the world is trying to put behind it. But carbon storage, once it comes online, will give the facilities a new function.

Chief executive O’Shea, who’s out to prove a point, describes the project as “truly huge.”

“It can store more carbon dioxide molecules than there are grains of sand in the Sahara desert,” he said in an interview during a recent visit to the site. “We need to speed up timelines massively, but we also need the support of government.”

The plan for Morecambe looks straight forward. Gas will contine to flow and be brought onshore for processing. Then, rather than venting the CO2 from the production, a pipeline will bring it back offshore in a “closed loop system” that allows simultaneous injection and extraction.

While Morecambe didn’t get support under the UK CCUS program, it already has a carbon storage license. And Centrica owns all the assets — the terminal, the pipeline — so it can press ahead with capturing its own emissions. (CCUS is a related concept, where CO2 is reused — the “U” in the acronym — rather than stored.)

The next stage is getting other industries involved, and heavy emitters, like the cement industry located in Britain’s Peak District, have signed up. But that means much more infrastructure investment, and it’s where government funding and support comes in.

“What you’ve really got is this kind of chicken and egg thing, which is who builds a pipeline across from the cement industry to Morecambe, from the emitters to Morecambe? And how do we make that work? ” O’Shea said. “The government, regulators have got to realize that you’ve got to be making decisions quickly because it can usually take you two years to do the engineering.”

Carbon capture and storage, or CCS, involves taking CO2 emissions, transporting them to a site — usually an old oil and gas field — and burying them.

It’s controversial, with critics saying it can help to extend the life of fossil fuels that should be winding down faster. It’s also expensive, and there’s a risk of environmental damage from leakage at storage sites.

But CCS remains in focus as a decarbonization tool because of slow global progress in reducing emissions. In the UK, worries about energy security and fuel prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government to issue new permits for oil and gas production in the North Sea. Other policy shifts have also raised questions about the UK’s ability to meet green targets, particularly its 2050 net zero goal.

Centrica’s CCS plans are centered on Morecambe in the Irish Sea, operated by joint venture Spirit Energy. Over the past four decades, Spirit Energy says the field has pumped out enough gas — more than 6.5 trillion cubic feet — to fill Scotland’s famous Loch Ness 25 times over.

Centrica currently expects to continue production until the end of the decade, having previous planned to stop in the mid-2020s.

The platforms there — mazes of pipes, bridges and rigging dotted with workers in bright orange overalls — are inextricably linked to the era of dirty energy that the world is trying to put behind it. But carbon storage, once it comes online, will give the facilities a new function.

Chief executive O’Shea, who’s out to prove a point, describes the project as “truly huge.”

“It can store more carbon dioxide molecules than there are grains of sand in the Sahara desert,” he said in an interview during a recent visit to the site. “We need to speed up timelines massively, but we also need the support of government.”

The plan for Morecambe looks straight forward. Gas will contine to flow and be brought onshore for processing. Then, rather than venting the CO2 from the production, a pipeline will bring it back offshore in a “closed loop system” that allows simultaneous injection and extraction.

While Morecambe didn’t get support under the UK CCUS program, it already has a carbon storage license. And Centrica owns all the assets — the terminal, the pipeline — so it can press ahead with capturing its own emissions. (CCUS is a related concept, where CO2 is reused — the “U” in the acronym — rather than stored.)

The next stage is getting other industries involved, and heavy emitters, like the cement industry located in Britain’s Peak District, have signed up. But that means much more infrastructure investment, and it’s where government funding and support comes in.

“What you’ve really got is this kind of chicken and egg thing, which is who builds a pipeline across from the cement industry to Morecambe, from the emitters to Morecambe? And how do we make that work? ” O’Shea said. “The government, regulators have got to realize that you’ve got to be making decisions quickly because it can usually take you two years to do the engineering.”

Spirit Energy estimates the project could store more than 5 million tons of CO2 per year at the start, rising in time to 25 million tons.

“Overall, the evidence is clear that the UK would have minimal chance of reaching net zero by 2050 without employing CCUS,” Esin Serin, a policy fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, wrote in a recent blog. But it “should be part of, not an excuse to delay, an overarching push for clean technologies,” she said.

The government has said CCUS will play a “critical role” in the move to net zero. There are currently more than 90 carbon capture and storage projects planned, enough for about 94 million tons of CO2 per year — equivalent to more than a quarter of total UK emissions, according to the UK’s CCS Association.

Yet, only a few industrial clusters have been selected across England and Scotland in a bid to kick start the industry.

Bas Sudmeijer, managing director and partner at the Boston Consulting Group, says the UK strategy has some benefits, but it “comes with trade-offs on pace.”

“It remains to be seen what model is ultimately most successful,” he said. “But the first CCUS Final Investment Decisions have now been taken in both Europe and the US, whereas in the UK that is not yet the case.”

The UK government has committed £20 billion for early deployment of CCS technology, including a £1 billion CCUS infrastructure fund. But though the underlying technology has been around for decades, high capital costs remain an issue.

A spokesperson for the Department for Energy Security said the government is committed to further development of carbon capture, utilization and storage.

“Everybody’s trying to do their best — the government, regulators, businesses,” said Jon Butterworth, CEO of grid operator National Gas Transmission Plc. But the UK needs a network to capture, transport and store carbon, and the issue needs a “bigger conversation.”

(By Priscila Azevedo Rocha and Elena Mazneva)

No comments:

Post a Comment