Celtic grievances have erupted once more, and can no longer be waved away by Whitehall

The legendary Welsh rugby star Phil Bennett, who died last month, would rouse his team against England, calling them “bastards … taking our coal, our water, our steel … They exploited, raped, controlled and punished us – that’s who you are playing.” It was fighting talk, only half in jest. It was Celts against the English.

In British history and politics, the Celts have grievances that wax and wane, but they never heal. They have erupted once more over Brexit and Ireland and in a revived demand for Scottish independence, a process Boris Johnson and latterly Keir Starmer have vowed to resist. The result of this relentless nagging pressure has been to make the boundaries of the United Kingdom among the most unstable in Europe.

That a once-imperial nation on a small archipelago in the Atlantic cannot hold its domestic union in place is astonishing. Partly underlying its disunity is a notional split of the population into “Celts” and “Anglo-Saxons”, based on a fanciful conquest of one by the other supposedly in the fifth century. Modern genetics has shown the divide to be meaningless, yet it is embedded in the politics of the so-called Celtic fringe – or at least in England’s reaction to it.

Traditional histories maintained that some time in the late bronze or iron ages a group of European tribes called Celts invaded and overwhelmed the ancient Britons, spreading their disparate but related languages over the entire population. They survived the Roman occupation intact but tradition again holds that, on the Roman retreat, they were overwhelmed in turn by invading Saxons. These invaders reputedly drove the Celts westwards and created an English empire of the British Isles. No trace of the preceding Celtic remained in its language.

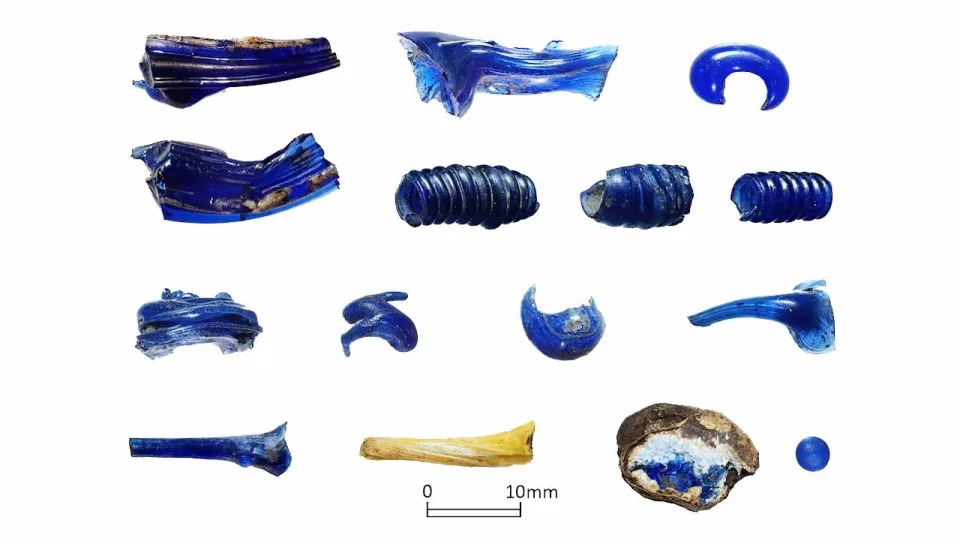

The details of both these invasions have long been challenged by scholars. In the 1960s, the historian JRR Tolkien dismissed the Celtic age as a “fabulous twilight … a magic bag”. The archaeologist Grahame Clark protested against “invasion neurosis”, the idea that all social change required a conquest. Since the 1990s, DNA archaeology has indicated that the diverse peoples of the British Isles were many and various, their settlement dating back to the stone age. As the prehistorian Barry Cunliffe has argued, today’s Celtic speakers probably migrated up the Atlantic littoral from Iberia long before anyone knew of Celts.

This might be of no account were it not for the manner in which the eastern Britons asserted supremacy over their western neighbours and maintained it ever since. From the Normans onwards, the rulers of the half of the British Isles called England created one of the most centralised states in Europe. Medieval wars against the Welsh and Scots and later conflicts with the Irish duly bred a passionate western and northern aversion towards the English. In the 19th century this was reciprocated by an English invention of a “Celtic” stereotype. Matthew Arnold dismissed Celts as “romantic and sentimental … lacking the temperament to form a political entity”, so unlike the “disciplined and steadily obedient” Anglo-Saxons.

It is significant that this collective abuse of the Welsh, Scottish and Irish never met a collective response. There was no Celtic solidarity, never one nation, language or culture, let alone a military or political alliance. To the English these peoples should see themselves as what amounted to English counties, like Yorkshire or Kent, to be assimilated into a “great British” union. Wales was forced to join in 1536, Scotland in 1707 and Ireland in 1801.

Wales came into union peacefully, Scotland grudgingly and Ireland never. Irish rebellions followed one after another until it won its independence in 1922. Thereafter a rump United Kingdom did cohere. It was sustained by a Tory unionist obsession and by a Labour party that saw it as embodying Aneurin Bevan’s “unity of the British working class”. Celts were for fairy tales and antiquarians.

This makes the more extraordinary what happened at the end of the 20th century. Infuriated by Thatcher’s centralism, in 1989 a majority of Scottish MPs demanded the return of a Scottish parliament. Seizing the moment, Labour’s Tony Blair would later deliver a modest devolution to new Scottish and Welsh assemblies. These assemblies sparked a sudden outbreak of regional identity politics. Nationalism surged back to life. In Scotland, the Tory party all but vanished.

In 2007, Scottish nationalists took power in Edinburgh and have never lost it. Though the popularity of independence among the Scots has risen and fallen, voters under the age of 50 are overwhelmingly in favour. The odds at present are on Scottish independence one day. Meanwhile in Northern Ireland, Brexit chaos has fuelled an expectation of a vote for reunion with the south in the future. Even in Wales, the nationalist Plaid Cymru has acquired new vigour, with support for an “independent” Wales at between a quarter and a third of voters.

The response of England to this burst of dissent has been inert. Across Europe, nation-building has been long been a vexed art. Violently in Yugoslavia and Ukraine, and relatively peacefully in Spain and Italy, central governments have struggled ceaselessly to hold the loyalty of their component peoples. As the political historian Linda Colley has shown, this has required respect for identity and ingenuity in devolution. German Länder enjoy considerable autonomy. Spain’s Basques and Catalans have degrees of economic, fiscal and judicial sovereignty. Swiss cantons even have differing definitions of democracy.

Britain’s Boris Johnson really could not care less. The prime minister has called devolution in Scotland “a disaster”. After Brexit, he insisted that all EU powers and subsidies be repatriated not to the devolved governments but to London. On trade, he appeases the wildest Northern Ireland unionism. A mere one in five of voters in England now profess to care if Scotland goes independent, yet Johnson fights to retain this first English empire with all the fervour of Edward I.

Advertisement

If I were Northern Irish, I would vote to rejoin the prospering south. If I were Scottish, I would wonder why I was once richer than Ireland and Denmark but am now poorer, and would opt for independence, whatever the pain. Yet I am neither of these things. I believe that a federated United Kingdom of England, Scotland and Wales benefits greatly from its diversity.

Lumping Celts together as one people and one problem that can be swept under a unionist carpet is demeaning to the ambitions of Irish, Scots and Welsh. It will not silence them. It will not help the search for what is now critical, a bespoke autonomy for each nation in a new British federation.

Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist. His book The Celts: A Sceptical History is published this month by Profile