Orientation

Christianity’s sinister past against Paganism

The very first commandment in the Bible says “I am the Lord thy God, thou shalt not have strange gods before me”. These Pagan Gods are claimed to be either unreal or false. Pagan statues were therefore fair game to be destroyed or desecrated. The story of the Christian destruction of the Greco-Roman Pagan world has been told by Robin Lane Fox in Pagans and Christians; Jonathan Kirsch, God Against the Gods; Catherine Nixey, The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of The Classical World and Helen Ellerbe, The Dark Side of Christian History. There is no secret about the horrible Inquisition of the Catholic Church against heretics such as Bruno and Galileo. Lastly, feminists have made us very aware of the burning of the witches, both in Europe and in the United States in Salem Massachusetts although there is controversy over how many women were killed.

The variety of ways Pagans react to Christianity’s sinister past

How do Neo-Pagans react to these historical events? As we might expect there is a full spectrum of reactions. The more militant feminists see all the monotheist “Religions of the Book” as their enemy, not just Christianity. The whole of “patriarchy” is the problem. Z Budapest and Monica Sjöö are examples of the more militant type. These heavy hitters do not want to make nice with Christianity and mix Paganism with any monotheistic beliefs or rituals. At the other extreme there are those Neo-Pagans who want to fight for Paganism to be included as a world religion and join the Parliament of the World’s Religions. Michael York’s book Pagan Theology is an example of this. In the middle there are Neo-Pagans who are basically Pagans but want to eclectically draw selectively from aspects of monotheist religion of the liberal type. River and Joyce Higginbotham in their book Pagan Spirituality are examples of this.

Where are we going?

Part of this article is a defense of militant Neo-Paganism against the more compromising positions. I say Pagans should be anti-Christian. Neo-Paganism will be compared to Christianity across thirty categories. The second part of this piece is about why Neo-Pagans should also be anti-capitalists. I will compare Neo-Paganism to capitalism across the same thirty categories. I will close this article by showing the close relationship between monotheism and capitalism across thirteen categories.

The Fundamental Opposition Between Neo-Paganism and Christianity

Patriarchal foundations of Christianity

Suppose we give the more compromising Neo-Pagans the benefit of the doubt for the sake of argument and let’s say we should forget the monstrous history of Christianity and try to work out a relationship with Christianity in the present. What this doesn’t consider is that Christianity is diametrically opposed to Paganism on ontological and epistemological grounds. For one thing, Paganism has had long historical periods in which it was centered in societies which were matrifocal though not matriarchal. It’s true that Poly-Theism existed in patriarchal societies as well, but there has never been a monotheistic society in which there was a matrifocal organization of descent or residency. Monotheism has been fundamentally opposed to gender equality.

Transcendental Nature of God

Secondly, the Pagan tradition has a history of the gods and goddesses as immanent in the world. Nature creates and recreates herself from within, without any extra-cosmic “butt-inskies” intervening. Nature is sacred. Christianity, on the other hand is foundationally a transcendental religion. Its God is above and beyond other worldly beings and sucks the sacredness out of the world. God shoots his wad before time and creates the world in a single act over seven days. But this leads to contradictions since God has to intervene periodically into history to fix what he botched.

Nature is imperfect and passive

God creates nature, nature does not create God. Nature is fallen and passive and receives its marching orders directly from God. Humanity is given the job of having dominion over nature. Nature is marginalized, a distraction at best, a temptress at worst.

God demands worship and obedience

Whether in animism or polytheism in all Paganism, reciprocity between humanity and the earth spirits, totems, ancestors, goddesses and gods, reciprocity is the name of the game. The gods and goddesses are not all-powerful and all-knowing and are somewhat dependent on humanity. This is the basis of magic. They are hardly in a position to demand obedience. For Christianity, God is worshipped. To worship is a one-way relationship going from humanity to God. God does not want nor need reciprocity. God acts arbitrarily in the case of the Jews and the Protestants. He causes suffering yet has to answer to no one.

Christian understands opposites as dualistic, mutually exclusive

For Pagans, all the spirits, totems, ancestors, gods and goddesses have strengths and weakness. There are no beings that are all good or all bad. For Pagans opposites are polar, they can turn into each other, creating new emergent synthesis. Christianity, on the other hand, creates absolute opposites of an all-good God who is all powerful, knowing and loving. But Christianity creates another being which is absolutely evil – Satan. Because of this Christianity has a difficult time providing guidance for human life which is too complex to be put into absolutist blocks.

God of Christianity is a warring, jealous, intolerant god

It is certainly true that there have been wars in animistic and polytheist societies, but these societies never went to war over religion. Neither were these sacred sources intolerant of each other. In general, when Pagan societies encountered other spiritual beings, they either tried to see the commonalties with their beings or simply added them to the pantheon. Their philosophy was kind of “the more the merrier”. The entire history of Christianity, on the contrary has been marred by religious wars between monotheist religions, intolerance of heretics, persecutions and fanaticism of witches that has no parallel in Paganism.

Christianity understands humanity has fallen and is in need of faith

There is no such thing as original sin in Paganism. People certainly have failings but as individuals. However, there was no mark of failure that condemned the entire species. In addition, Paganism was an experiential religion. People practiced magic and sometimes it seemed to work and sometimes it didn’t but no faith in the sacred powers was required. The goddesses and gods had to be persuaded or lured but the reciprocity made faith meaningless and irrelevant. For Christianity we have the Adam and Eve tale of original sin. Humanity was cursed and was lucky to be alive. God could do whatever He wanted and humanity was expected to have faith that in the end God would show some mercy.

Most Christianity must hollow out intermediate beings

Pagan loyalties are both close at hand and far away. Furthermore, there is rarely a hierarchical relationship among sacred beings. There are earth-spirits, totems, ancestor spirits, culture heroes, goddesses and gods and each covers an expanding range of responsibility. However, gods and goddesses don’t tell earth-spirits or ancestors what to do. They each exist in an expanding plurality. In the case of Christianity, not only is there a hierarchical relationship between God and humanity, but God must wipe out all Pagan intermediaries in the extreme case of the Protestants and the Jews. For them it is the human individual, God and the Bible. Catholicism does allow intermediaries such as angels or saints, provided they are subordinate to God.

Christianity aspires to spiritual imperialism

Pagan societies at the tribal level have always been local and decentralized. Polytheistic state civilizations have been centralized politically but there is not a single centralized Pagan tradition in those societies. Usually, the peasants practiced their own kind of “earth magic” while those in the cities practiced a more urban polytheism. But even the rulers of polytheistic state civilizations did not proselytize their religion or send out missionaries. If they conquered other societies, they simply expected the subjugated population to respect their gods and goddesses while pretty much leaving subordinated groups alone to practice their own traditions. It is Christianity that began to proselytize once it gained state power, sending out missionaries in the hopes of converting everyone worthy of becoming Christian. Just as for Christians, God is imagined to be everywhere in the spiritual universe, so Christianity on earth must also be everywhere conquering the entire globe.

Table 1 contains a more exhaustive list of contracts between Paganism and Christianity. I have drawn this list from Jordan Paper’s book The Deities are Many.

Christianity as a slave religion of sick weaklings filled with resentment

At least among philosophers, I can’t think of a stronger critic of Christianity than Fredrich Nietzsche. He famously announced that “God is dead”. Unfortunately, some have interpreted this as meaning Nietzsche was some kind of atheist. Given Nietzsche’s love of the Greeks and what he imagined as early German Pagan culture, he should have said, “God is dead. Long live the gods!”. Nietzsche rightly criticized Christianity as a slave religion, a religion of a “domesticated animals, herd animals, a sick animal”. When we look at the history of Christianity it has been a history of followers, and a religion that justified oppression for the overwhelming period of its history. What did he mean by a calling Christians sick animals? Many things. For one it is a religion of passivity, a religion that gets its followers used to meekly following orders rather than seeking out spiritual experience, as he said, dancing on the slopes of Vesuvius. Christianity attempts to get people used to pining for pie in the sky waiting for them when they die.

It is also sick because it is a religion which makes a virtue out of being weak. Nietzsche says somewhere I love to see those without any claws making a virtue out of being clawless while condemning health and strength as a vice and something to be stamped out. Nietzsche said that Christian parasites in power make an ideal out of whatever contradicts self-preservation, pleasure, joy and most everything we Neo-Pagans stand for.

Nietzsche discussed resentment as the psychology of Christians. The psychology of resentment makes a virtue of wishing ill on other people while envying what they have. Nietzsche had no patience with Buddhism’s attempting to starve out desire or meditating it away. He thinks it is far braver to have like a Centaur’s desire without the desires having us. We supersede our desires; we don’t transcend them. To transcend means to be above and superior to our desires, being beyond and fundamentally unlike them. On the other hand, to supersede desires is to fully indulge them yet wanting more, and having wings to ride them into a higher dimension. Nietzsche saw Christianity as a war of the botched against the fit. A war of slander against the here and now. Any creature who would need faith and prayer is corrupted by the virus of Christianity.

I hope I have convinced you Neo-Pagans that I have made a good case that we need not wander into Christianity imagining they have something we lack. Both historically, ontologically and epistemologically it is against everything we stand for. I will now take on objections from Neo-Pagans who want to take a softer line.

What can Christianity Possibly Offer Neo-Pagans to Make Us Think Twice?

An identification with western esoteric vs exoteric spirituality

Some Neo-Pagans might say that militant Neo-Pagans are too extreme. For one thing, there are liberal Christians who would themselves criticize the history of Christianity and be sympathetic to Neo-Pagans. New Age spirituality makes a distinction between esoteric and exoteric spirituality. They contend that at their best, all world religions are good and all the world religions take different paths to the same end. This commonality across religions is known to only the few, and this comparative understanding of religion is called the perennial philosophy or esoteric spirituality. Transpersonal psychologist and comparative religion scholar Ken Wilber in his books Up from Eden and Sex, Ecology, Evolutionexemplify this esoteric vs exoteric spirituality. The Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky and the Anthroposophy of Rudolph Steiner are more historical examples.

On the other hand, exoteric religion is the religion of the masses. It is the leaders of exoteric religions who are responsible for all the religious wars between the religions of the book as well as Catholic and Protestant attacks on Paganism. So esoteric New Age spiritualists hold out the olive leaf to Neo-Pagans, welcoming us in. Why not take the leaf? For one thing the perennial philosophy is a synthesis of universalistic religions which include Eastern religions/philosophies like Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism and Confucianism. They are all patriarchal religions and as I have tried to show the Pagan world view is diametrically opposed to them.

Furthermore, those who support the perennial philosophy are people from upper middle-class backgrounds. This is only about 10% of the population. In the United States 14% do not identity with any religious heritage. The overwhelming majority of middle-class and especially working-class people – 75% of the population – identify with either the moderate or fundamental spectrum of monotheism. So, the characteristics of monotheistic Christianity on the right side of Table I are accurate for most Christians.

Pragmatic considerations of a lack of stable public space

In addition, we militant Neo-Pagans have to admit that we do not have any public space for regular practices. At least in Yankeedom, there are no Pagan temples in which we can hold rituals and ceremonies. The Unitarian Universalists now offer Neo-Pagans a free space to use in the church and be part of it. It is tempting, yet for militant Neo-Pagans there are class issues. The Unitarians are among the wealthiest of the Protestant churches in the United States. For militant Neo-Pagans who are socialists – whether anarchist or Marxists – mixing with the upper classes raises contradictions. The problem of lack of stable public space means that for those who are not solitary Pagans, at the local level covens will continue to be held in private homes. At a regional level, while conferences and seasonal festivals have been very successful in state parks and private campsites, we still have no place to call home.

Legal protection

In the United States, Neo-Paganism has flourished from the late 1970s to today. For the most part we have been left alone by the Catholic, Protestant and Zionist authorities. However, all these religions have seen a decline in their numbers. At least one of the reasons for this is people, especially women, have left it for Neo-Paganism. Especially in the era of Trump 2.0, Neo-Pagans have good reason to fear a new kind of persecution from Catholic and Protestant fundamentalists. This is why some Neo-Pagan groups want to apply for legal status to protect themselves from harassment. But militant Neo-Pagans are concerned that preoccupation with legal standing will conservatize the movement and drain its radical, in-your-face edge way of life. In addition, living in a steeply declining civilization such as the United States, economic and political insecurity can make life much harder for Neo-Pagans that it has already been.

Civil disobedience

A more militant approach is to organize now to prepare for an attack rather than waiting until it happens and then operating in reactive mode. The more radical wing of Paganism such as Starhawk’s Reclaiming group has lots of experience with organizing Pagans into political protests using the methods of civil disobedience. These strategies and tactics could be transferred to standing-ready groups in dealing with Christian nationalists. Neo-Pagans would do well to make alliances with atheists and secularist groups such as Freedom from Religion. This group is very well organized and consists of lawyers and lay folk who defend the Constitution against Christian nationalists who try to cross the line in the separation of Church and state. They have a monthly newspaper and hold conferences once or twice a year.

Armed conflict

As citizens of the United States, we are allowed to bear arms. Most of the time people think of this as something individuals do. But there is nothing to help Pagan groups protect themselves against Christians collectively if they are attacked. Usually, liberal Pagans get nervous with talks about group arming. Also, people think that this kind of thing is inherently a right-wing activity that might be associated with the Nordic Paganism, some of whom have a racist orientation. However, there is another left-wing organization called Redneck Revolt which is anti-racist and appeals to working-class whites who are Socialists. They believe in protecting working-class people collectively. Read here for more information about them. There is certainly a lot to learn from them in applying their organizational skills to Neo-Pagan circumstances.

What I have said so far is that Neo-Pagans should keep their distance from Christianity for theoretical reasons and practical reasons. But suppose you continue to object. Ok, I will make one concession

A twelve-step program for Christians to join the Neo-Pagan community

In my opinion some Neo-Pagans are far too accommodating of former Christians who want to jump on the Neo-Pagan bandwagon. They should be required to go through the equivalent of a 12-step program in order to have a chance at being part of a Neo-Pagan community. They should be required to read at least two books about the history of what Christianity has done to Pagans, one for the ancient world and one on Christian attacks on witchcraft. As part of their initiation, they should be required to respond a list of questions. The third process they should enact is to write down the history of any harm they might have done to Neo-Pagans in the past including any high-school encounters. The fourth is to, as much as possible, track those people down who have been harmed and make amends. Next, as part a public ritual they should make a public apology to the entire Neo-Pagan community. Finally, they should be given some volunteer work within the Neo-Pagan community to do such as making phone calls, mailing newsletters or driving equipment around to Pagan events. This would relieve the burden from committed Neo-Pagan leaders who are probably overworked and underpaid for the time they put into their organization.

Table 1 Paganism vs Monotheism (Christianity)

| Paganism | Category of comparison | Monotheism (Christianity) |

| Matrifocal cultures developed polytheism | Matriarchy vs patriarchy | No matrifocal cultures ever developed monotheism

No record of a monotheistic Goddess theology until contemporary feminism |

| Never celebrated celibacy | Place of celibacy | Catholic and Buddhist priests are celibate |

| Many truths | Tolerance | Single truth can produce intolerance. No grey areas |

| No heresies. Experiential | Heresies | Based on creeds – heresies prevalent |

| Generally, the gods and goddesses are not jealous of each other | Jealousy | Yahweh is jealous |

| No | Persecution | Yes. Ex-communication

Christianity went from a persecuting minority to a persecuting majority |

| No | Fanaticism | Yes. Destroying the Alexandrian library, smashing of idols (Protestants) |

| No wars over beliefs | Wars | Religious wars over beliefs |

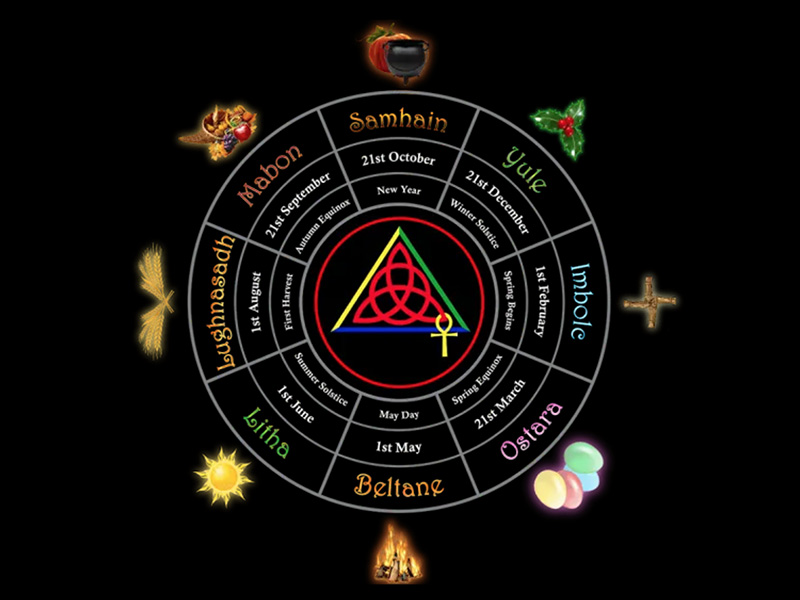

| Cyclic | Time orientation | Linear time |

| Sacred | Earth and nature | Marginalized – desacralized |

| Ongoing creativity in time and space | How frequently is creativity used | Creative in a single act before time |

| Many directions: horizontal | Directions | Single vertical direction

Heaven above, Hell below |

| No original sin other than human selfishness | Original sin | Yes. Inheritor of Adam and Eve’s sin |

| Opposites are polar and change into each other | The Nature of opposites | Dualistically separated and going in opposite directions |

| No. All gods and goddesses have their pros and cons | Distribution of virtues and vices | God absolute god

Satan absolute evil |

| Reciprocity, respect, reverence | How is the sacred engaged | Worship, obedience |

Looked down upon

Wealth is land based – foragers, horticulturalists, agriculturalists | Place or misplace of commerce | Made room for it

Originated among Greece, Phoenicians. Herders |

| | Christianity spread in port cities In Turkey |

| | Islam spread along the caravan routes of Central Asia |

| | Catholics in Venice |

| No proselyting, no missionaries | Outreach | Proselytizing, missionaries |

Decentralized – Paleo-Pagan

Centralized – Meso-Pagan

Decentralized – Neo-Pagan | Coordinated effort | Centralization once they had power |

| Local, regional at most | Spatial reach | Global, everywhere |

Ancestors are very important among horticulturalists

(reverence) | Place of the ancestors | Not very important |

| Social situations when the family was embarrassed | Shame vs guilt | Guilt was not group focused Individual God

Guilt is continuous and unending |

| Gods are not all-powerful or all-knowing | Degree of power | God is all powerful

God knows all |

| Meaningless and irrelevant | Faith | Meaningful, necessary and relevant |

Mediums are ongoing and a way of life – women

About past, present and future | Intermediaries | Only under extraordinary events

Prophesy – men

About the past |

No origin. World is eternal

cyclic, steady state | Origin of universe | World has origin

Big bang |

| Myths change over time | Stability of myths | Myths are fixed and unchanging over time |

| Tricksters, playful and prevalent | Place of trickers | These stories exist in West they are not numinous. They can be associated with evil as with horror — or cartoon characters

Deities that are numinous – are serious about sobriety |

Neo-Paganism vs Capitalism

Merchants and artisans are not capitalists

In this section I will give many reasons why Neo-Paganism should want nothing to do with capitalism. But does this mean Neo-Pagans should be socialists? Yes, but I will not make the case in this article. Many Neo-Pagans are justifiably cautious about socialism if they think socialists want the state to be in charge of all economic exchanges. They fear socialists will deprive them of their livelihood. After all, many Neo-Pagans have found their new identity from inhabiting Neo-Pagan bookstores. The owners of these bookstores and occult magic stores are merchants. Furthermore, a solid core of Neo-Pagans are artisans who make jewelry, craft calendars and make sculptures of gods and goddesses.

From our point of view merchants, artisans and craftsmen are not capitalists. Markets and artisans existed all the way back to simple horticulture societies long before capitalism existed. Industrial capitalism is the private ownership of natural resources, methods of harnessing energy, tools and power settings (politics) where decisions are made about what to produce and how to produce it. These forms of capitalism include agricultural capitalism (slavery), industrial capitalism, finance capitalism and military capitalism. It is these that Neo-Pagans should be against. But how is capitalism the deadly enemy of Neo-Paganism?

No reciprocity and infinite exploitation

The heart of Neo-Paganism is that the relationship with the sacred powers is reciprocation. It is the basis of sympathetic magic. Our relationship is based on respect and reverence between us and our totems, ancestors, gods and goddesses. The gods and goddesses do not take and take and take. That would lead to breakdown. But under capitalism there are no lawful expectations that capitalists must give back. They are free to exploit as much as they can get away with. It is true eventually capitalism cannot go on this way and the results are either economic depressions or revolutions. So, workers are in the long run sometimes compensated. But this happens socially, unconsciously. It is not something that is built into the system of capitalism by capitalists. Workers may be reciprocated but in spite of capitalists.

Capitalist idolatry

In spite of Christian propaganda, Pagans do not idolize our gods and goddesses. Sacred powers are generally understood as fluid, moving and changing. We don’t treat these sacred powers in a Platonic way where spirits are essences, Platonic ideals which are frozen and changeless. In Neo-Paganism there is little in the way of reification, in which gods take on a life of their own, where the tools or objects used are reified. It is true that some of the more superficial tendencies in Paganism might reify magical tools and treat them as ends in themselves. But this is true of any common superstition, not unique to Paganism.

However, the entire capitalist system is based on idolatry of commodities and money. In the first volume of Capital, Marx talks about the idolatrous relationship between workers and the commodities we make. Instead of commodities being used as means to consume and improve life, we reify commodities until they become ends in themselves. We become enslaved to our commodities and live through the possession of them. As Marx says, things are in the saddle. Commerce is unhinged and everything is for sale.

Secondly, money becomes a fetish instead of a means to gain commodities. In the merchant phase of capitalism, money is used as a medium to facilitate the exchange of commodities. But under the industrial phase of capitalism money changes from a means to an end to an end in itself. Money is invested in commodities, not to use the commodities but as a means to make more money. Money becomes fetishized as capital. These reifications can be tracked in our language as when we hear phrases like “money talks’ or “let your money grow” as if money were a part of organic life. Lastly, under finance capital, capital is used to make more capital and becomes completely unhinged from social life. Derivatives and stock options are reified monsters who dictate social life. The stock markets are the houses of idolatry where the traders pay homage to Mammon.

Capitalism is imprisoned in dualistic opposites

As I said in the section on monotheism opposites, Neo-Paganism understands opposites as polar, as turning into each other and as mutually co-creative. Under capitalism opposites are understood as mutually exclusive opposites:

- Workers vs capitalists

- Capitalists vs communists

- Hardworking, thrifty, shrewd capitalists vs lazy, ignorant workers

But more importantly, capitalists do not understand the contradictory nature of their system. They image their system can go on forever. Capitalists image that their significant problems about every seven years are “businesses cycles” which are self-correcting. They deny that capitalism has accumulating contradictions, which past a certain point will either degenerate into a lower order or be transformed into a higher system, a qualitative leap. As Rosa Luxemburg once said, “it’s either socialism or barbarism”. Marxist crisis theorists present various ways in which the system will end. David Harvey in his book The Seventeen Contradictions of Capitalism lays this out beautifully.

Capitalists Must Destroy Intermediaries

As I said earlier in our discussion of spiritual intermediaries, for Pagan intermediaries are welcome and they expand seemingly without limit and without a hierarchical relationship between them. At the origin of capitalism, merchants had to compete with feudal economic exchanges which cut across political intermediaries such as kingdoms, provinces, principalities and city states. Over the last 500 years capitalist used nation-states to hollow out or eliminate these political intermediaries. They used the nation-state to climb under, around and through kingdoms and provinces so that capitalist exchanges through coined money was the only game in town. Then under global capitalism the organization of societies into nation-states becomes hollowed out so that whole continents (the European Union) began to undermine nation-states.

Capitalist have overreach in spatial scale

As I said earlier, Paganism’s spatial reach is decentralized and local. Capitalists, however know no spatial limits. It first expands into nation-states but when it runs into problems in making a profit within its home nation-state it expands beyond it. There are problems within nation-states either because there is competition between capitalists in other nation-states or because its domestic workers are getting more organized to fight exploitation through unions or revolutions. They keep expanding across the globe, subjugating societies as they grow toward imperialism.

Exploitation of Nature

Just as capitalists know no limit in the exploitation of other societies, so in the biophysical world it exploits nature without limits. The result of ecological pollution is extreme weather, desertification of lands, species growing extinct, feedback systems in nature that run amuck. Instead of replenishing and repairing, we hear capitalists treating the consequences of their attack on biophysical nature as “externalities” which they see as separate from economic exchange.

Please see Table two for a full comparison between Neo-Paganism and Capitalism at the end of this article.

Table 2 Neo-Paganism vs Capitalism

| Neo-Paganism | Category of comparison | Capitalism |

| Matrifocal cultures developed polytheism | Matriarchy vs patriarchy | Continues patriarchy with some presence of feminism |

| Never celebrated celibacy | Place of celibacy | Doesn’t supply celibacy

No money to be made from it |

| Many truths | Tolerance | Cannot tolerate any socialism in the world system |

| No heresies. Experiential | Heresies | Yes. Heterodox economists who are isolated are rarely department heads |

| Generally, the gods and goddesses are not jealous of each other | Jealousy | Capitalists jealous of competing economic systems |

| No | Persecution | Yes. Of its own working class and the oppressed workers’ and peasants’ western imperialism |

| No | Fanaticism | Ideology of private enterprise

Ideology of capitalism |

| No wars over beliefs | Wars | Wars against non-western countries and against socialism |

| Cyclic | Time orientation | Linear, especially after the industrial revolution. Time clocks, 14-hour days |

| Sacred | Earth and nature | Exploitation of nature. Pollution treated as “externality” |

| Ongoing creativity in time and space | How frequently is creativity used | Ongoing but unconscious collective creativity of workers |

| Many directions – horizontal | Directions | Vertical – class struggle between capitalists and working class |

| No original sin other than human selfishness | Original sin | None |

| Opposites are polar and change into each other | The nature of opposites | Dualistic: Mechanistic materialism vs idealist subjectivism |

| No. All gods and goddesses have their pros and cons | Distribution of virtues and vices | Capitalism has virtues – hardworking, thrifty, shrewd

Socialist have vices

Lazy, want something for nothing |

| Reciprocity, respect, reverence | How is the sacred engaged? | No reciprocity – infinite exploitation |

| Looked down upon Wealth is land based – foragers, horticulturalists, agriculturalists | Place or misplace of commerce | Unhinged commerce everywhere |

| Not a virtue | Suffering | No value in suffering Strive for hedonism |

| No. Earth spirits, rivers, gods and goddesses are moving | Idolatry | Yes. Commodity fetishism

Stock market – money talks |

| | |

| No proselyting, no missionaries | Outreach | Capitalist imperialism covers the globe |

Decentralized – paleo-Pagan Centralized – MesoPagan

Decentralized—Neo-Pagan | Coordinated effort | Both decentralized competition Monopolistic corporate centralization |

| Local, regional at most | Spatial reach | Global, everywhere |

| Ancestors are very important among horticulturalists (reverence) | Place of the ancestors | Elderly not respected

No ongoing homage

Youth culture |

| Social situations when the family was embarrassed | Shame vs guilt | Guilt for working class for not becoming wealthy |

| Gods are not all powerful nor all knowing | Degree of power | Capitalists do have absolute power of monotheism, but they have oligarchic power |

| Meaningless and irrelevant | Faith | Faith in “business cycles” and market corrections that the system will never crash |

| Mediums are ongoing and way of life – women are primary – About past, present and future | Intermediaries | Prophets intervene with market corrections and Federal Reserve interest fluctuations |

| No origin. World is eternal Cyclic, steady state | Origin of universe | Steady state capitalism imagined to go on forever Capitalism at the beginning

Adam Smith “truck and barter” |

| Myths change over time | Stability of myths | Myths do not change – American dream possible for everyone |

| Trickers, playful and prevalent | Place of trickers | Yes. Market is unpredictable and not subject to law |

| Inner – immanence | Source is inner or outer | Transcendence –

Fictitious finance capital, otherworldly with no investment in real goods or infrastructure |

Commonalities Between Christianity and Capitalism

- Both are patriarchal but capitalist systems had to deal with waves of feminism in the last 200 years.

- Each are intolerant– Christians of Pagans; capitalists of socialism

- Each have heresies – Christianity has religious heretics, witches; under capitalism, heterodox economists who are opposed to mainstream economics

- Both Christianity and capitalism have wars — religious wars between Christians and Muslims and capitalist wars against other capitalism nations; imperialist wars against their colonies; economic wars against socialism

- Both Christians and capitalists see nature as subordinate – Christianity says humans have dominion over nature whereas capitalists exploit nature

- Both Christians and capitalists hollow out intermediaries. Christians want to eliminate earth spirits, totems, ancestor spirit, goddesses and gods. Capitalists marginalize intermediate decentralized political bodies such as provinces, principalities, kingdoms and city states in favor of nation-states

- Spatial reach is global – proselytizing missionaries are all over the globe

Capitalist imperialism is spreading everywhere. Just as God is everywhere, capitalism is everywhere

- Both have a linear sense of time. Under capitalism with the invention of clocks, wrist watches, and time cards during the industrial revolution

- Both have a dualistic sense of mutually exclusive opposites

- Christianity or capitalism depreciates and marginalize the ancestors. Under capitalism there is youth culture to replace respect for the elders

- Both require faith. Christianity in an arbitrary and unpredictable god; capitalism in “business cycles’ and “market corrections” which explain away capitalist crises

- Divine intervention – unpredictable appearances of prophets in the case of Judeo-Christianity; Federal Reserve for capitalist interventions

- Value of transcendence – for monotheism a god who is above, before and beyond the world. For capitalism, finance capital – money made on money without any involvement in the production of goods and services

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to persuade Neo-Pagans to take a more militant stance against both Christianity and capitalism. I began with a brief discussion of how Christianity persecuted Pagans both at the end of the Roman empire as well as in early modern Europe with both the Catholic Inquisition and the witch hunts in Europe and in Salem Massachusetts in the US. I identified eleven ways in which Christianity and Paganism are diametrically opposed to each other in irreconcilable ways. I then presented three objections more compromising Neo-Pagans might make in arguing I am being too hard on Christianity. I rebutted them but gave them the benefit of the doubt in claiming that any ex-Christians who want to join Neo-Pagan circles should have to undergo a kind of 12-step program before they are allowed in.

In the second half of my article, I turned my attention to the relationship between Neo-Paganism and capitalism. I began by addressing the concerns Neo-Pagans may have in my opposing capitalism. I point out that being against capitalism does not mean I am opposed to Neo-Pagan bookstores, occult supply stores or artisans selling their work. These are market transactions. Markets have existed throughout much of history long before capitalism. Capitalism is a much more all-encompassing and controlling economic system that is way beyond exchange between merchants. I then named six ways in which capitalism is fundamentally opposed to Neo-Pagan ways of life.

In the last part of my article, I briefly identify thirteen ways which Christianity and capitalism share in common. What is unstated is what is the relationship between Neo-Paganism and socialism? For that I direct the reader to my book The Magickal Enchantment of Materialism: Why Marxists Need Neo-Paganism.

You can also find some of my articles in the “Perspective” section of our website Socialist Planning Beyond Capitalism.

Bruce Lerro has taught for 25 years as an adjunct college professor of psychology at Golden Gate University, Dominican University and Diablo Valley College in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has applied a Vygotskian socio-historical perspective to his three books found on Amazon. He is a co-founder, organizer and writer for Socialist Planning Beyond Capitalism. Read other articles by Bruce, or visit Bruce's website.