ByAnam Khan

Published: February 12, 2026

Lawrence Herman, international trade lawyer at Cassidy Levy Kent LLP, joins BNN Bloomberg to discuss the likelihood of U.S. ending CUSMA.

Separate bilateral agreements could still be beneficial if the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) falls apart, explains an international trade lawyer.

His comments come after reports that U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer suggested this week that the U.S. is considering negotiating separate trade deals with the two countries rather than maintaining the trilateral pact up for review on July 1.

The possibility of this even happening was envisaged from the very start, when there were talks of CUSMA coming under review, Lawrence Herman, international trade lawyer at Cassidy Levy Kent LLP, told BNN Bloomberg.

Herman said separate bilateral deals would not be easy, but could be done.

“There are a lot of provisions in the CUSMA that could be used in a bilateral agreement with Canada, as well as a separate bilateral agreement with Mexico,” said Herman.

‘We will have an aggressive partner on the other side’

Negotiations will be difficult whether they are three-party or bilateral between Canada and Mexico, said Herman.

“The point is, we will have an aggressive partner on the other side,” said Herman.

“I think Canada has to be prepared to say, you know, these are the red lines, and there are certain things that Canada cannot accept.”

At the end of the day, he said Canada must decide how much longer it can remain at the table if the other party is unwilling to reach a mutually satisfactory arrangement.

“The priority is to ensure that we get out from this volatile, uncertain, unstable relationship,” said Herman.

He also said many major companies in the U.S. are dependent upon free trade and fair trade with Canada, highlighting Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s recent pushback after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to block the opening of the Gordie Howe International Bridge. She called it “a really important part of our economy.”

‘Canada has been regrettably wedded to the U.S. market’

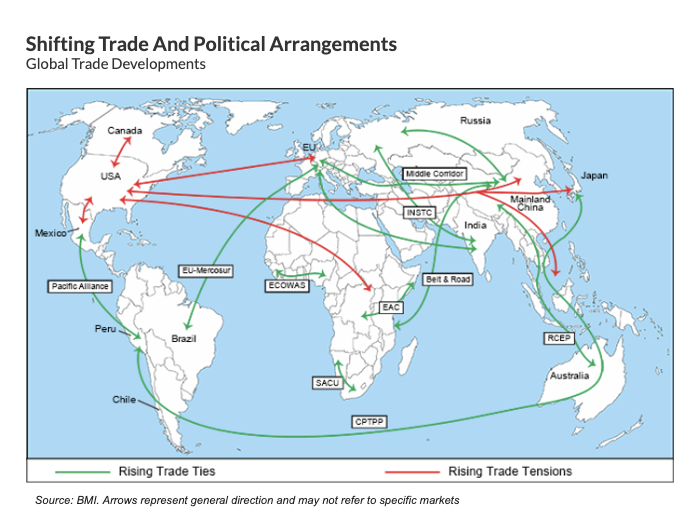

Canada has opportunities to expand in other markets, and the government has been looking at those opportunities to diversify its trade, but the reality is, “Canada has been regrettably wedded to the U.S. market,” said Herman.

“It is always a bad business practice to be so dependent on one customer, because that customer can turn ornery, as this customer, the U.S. has done so,” said Herman.

“There are so many things that tie Canada and the U.S. together that I cannot see things going forward without some kind of agreement.”

Canada is already in another agreement with Mexico

Herman noted that Canada and Mexico already have a trade agreement outside of CUSMA called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which includes 11 Pacific Rim countries. The U.S. withdrew from the original agreement in 2017.

“Mexico is party to the CPTPP, and so there would be an ongoing arrangement between Canada and Mexico,” said Herman.

He also said it would be better to have a straight bilateral agreement if the whole trilateral CUSMA falls apart.

Anam Khan

Journalist, BNNBloomberg.ca

February 11, 2026

CALGARY — A former U.S. State Department official says he’s optimistic the Canada-U.S.-Mexico free trade agreement will be renewed.

Edward Fishman, author of “Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare” shared his outlook during a luncheon hosted by the University of Calgary’s Haskayne School of Business.

The Columbia University adjunct professor says he can imagine Canadians feel like “sitting ducks” as their closest trading partner bombards adversaries and allies alike with tariff threats.

But he says the trading relationship doesn’t just flow one way and the U.S. would suffer significant economic harm if trade with Canada were to be cut off.

Fishman says U.S. political and business leaders — even those with a conservative bent — feel strongly about the importance of cross-border trade and are likely to temper President Donald Trump’s daily whims.

He says the countries that have been best able to withstand U.S. tariffs have been the ones that have shown the most resolve, resilience and willingness to retaliate, citing India, Brazil and China as examples.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Feb. 11, 2026.

Lauren Krugel, The Canadian Press

By Spencer Van Dyk

The agreement, inked during Trump’s first term, is up for review this year. In 2018, Trump called it the “most modern, up-to-date, and balanced trade agreement in the history of (the United States),” but just last month called it “irrelevant.”

“I don’t think I can answer that question,” Kirsten Hillman told CTV Question Period host Vassy Kapelos in an interview airing Sunday, when asked if she believes Trump wants to keep CUSMA in place.

“I think if the president has a strong view around the U.S. being able to do more itself, how that translates with respect to this treaty, I don’t know,” she added. “He says different things at different times.”

The U.S. and Canada remain in the throes of a trade war, which began last February when Trump imposed a slate of sweeping tariffs on Canadian imports.

Hillman, meanwhile, announced in December she would be stepping down as ambassador to the United States. She has represented Canada in D.C. for nearly six years and played a lead role in the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) before that.

“I think for Canada, what’s important is that we just keep working consistently with those — and there are so, so many of them in all three countries — that understand factually why that treaty keeps American business more competitive, creates more jobs and keeps their economy in a good place,” Hillman said of the future of CUSMA. “And I think that a lot of people are getting that message to the president.”

In an interview for CTV Question Period last month, Business Council of Canada president and CEO Goldy Hyder said he’s optimistic, based on his dealings with U.S. officials and business leaders, that CUSMA can be salvaged despite recent rhetoric.

“Yes, there’s a lot of noise; it’s not straight line,” he said. “Yes, it’s going to be complicated to get there. But there’s a recognition that this agreement is important for all three countries.”

And, this week, Conservative MP — and longtime friend of U.S. Vice-President JD Vance — Jamil Jivani travelled to Washington for a solo diplomatic mission to meet with senior U.S. officials, calling the conversations “productive.”

Asked if she were staying in the ambassador role, what would be keeping her up at night, Hillman said Canada has to “find a way to have serious, professional, technical trade discussions with the Americans,” while working toward making the Canadian economy more self-reliant.

“I think we need to not take our foot off the gas on either of them, while at the same time trying our best not to get knocked off course by the inevitable sort of distractions and diversions that always come up here in Washington,” Hillman said.

‘Geography can’t be undone’: Hillman

Asked to reflect on her time as ambassador and the state of the Canada-U.S. relationship, Hillman said it’s important people understand the degree of interaction and co-operation between the two countries’ administrations.

She said 13 different ministries are represented at Canada’s embassy in Washington, pointing to transport, energy, environment and finance as examples.

“Something comes up every day, and it’s not always problems,” she added. “Often it’s good things that we’re trying to celebrate, that we’re doing together.”

“I think geography can’t be undone,” Hillman also said, when asked whether that interconnectedness and interdependence is hard to undo.

The outgoing ambassador said while there are “a lot of feelings” and “a lot of disruption” in the relationship because of Trump’s policies, people-to-people ties “are deep and wide.”

“I don’t think we’re going to go back to where we have been in the past with the United States,” she said. “I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing.”

“I think, in large part, both of our countries took each other for granted,” she added. “I don’t think that’s the case anymore, but that doesn’t mean that those relationships that are so broad and deep won’t continue to be a source of inspiration as we chart whatever this new path is with our neighbour.”

After she officially wraps up her tenure as Canada’s ambassador to the U.S. this month, Hillman is set to return to Ottawa, though she has not announced which role she’ll take on next.

Canadian business executive Mark Wiseman is set to take on the role of Canada’s ambassador to the United States later this month.

With files from CTV News senior political correspondent Mike Le Couteur

Spencer Van Dyk

Writer & Producer, Ottawa News Bureau, CTV News