(RNS) — The nonprofit Shefa integrates Jewish beliefs and rituals with legal psychedelic practices, an approach that’s especially resonated in recent years.

A Star of David mosaic in Jerusalem. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

Kathryn Post

October 29, 2025

RNS

(RNS) — For nearly two decades, Larry Hertz, a 64-year-old professional, had found healing and spiritual enrichment through underground ceremonies where he and others took psychedelics. But there was a part of him missing: Raised in a culturally Jewish home in California’s Bay Area, he found that few in psychedelic circles knew much about Judaism; if religion was present, it was usually Christianity.

At the same time, his psychedelic practice made him feel as if he were living a double life.

“I think a lot of times when you’re in the medicine world, you can feel very isolated because it’s below ground,” Hertz told RNS. “A lot of my friends, I couldn’t tell them that I was taking medicine.”

That changed last year when an online search led him to Shefa Jewish Psychedelic Support, a spiritual community that, according to its website, bolsters “Jewish psychedelic explorers in North America and abroad.” Shefa does this by conducting psychedelic-fueled retreats that integrate Jewish beliefs and rituals, as well as by hosting a mix of events, from Purim dance parties and Hanukkah gatherings to courses in breath work and other healing techniques.

Rabbi Zac Kamenetz. (Photo courtesy of Shefa)

If its mission statement emphasizes exploration, Shefa’s focus is just as much aimed at healing, especially for American Jews grappling with trauma and fractured identities in a post-Oct. 7 world. “We know people are holding a lot of trauma, whether it’s conscious, unconscious, immediate with their own trauma, or ancestral,” said Shefa’s founder, Rabbi Zac Kamenetz. “We’re not going to resolve a global crisis, but we are going to be ourselves in the pain, the alienation, the anguish, the anger, whatever side you’re taking, or taking no sides.”

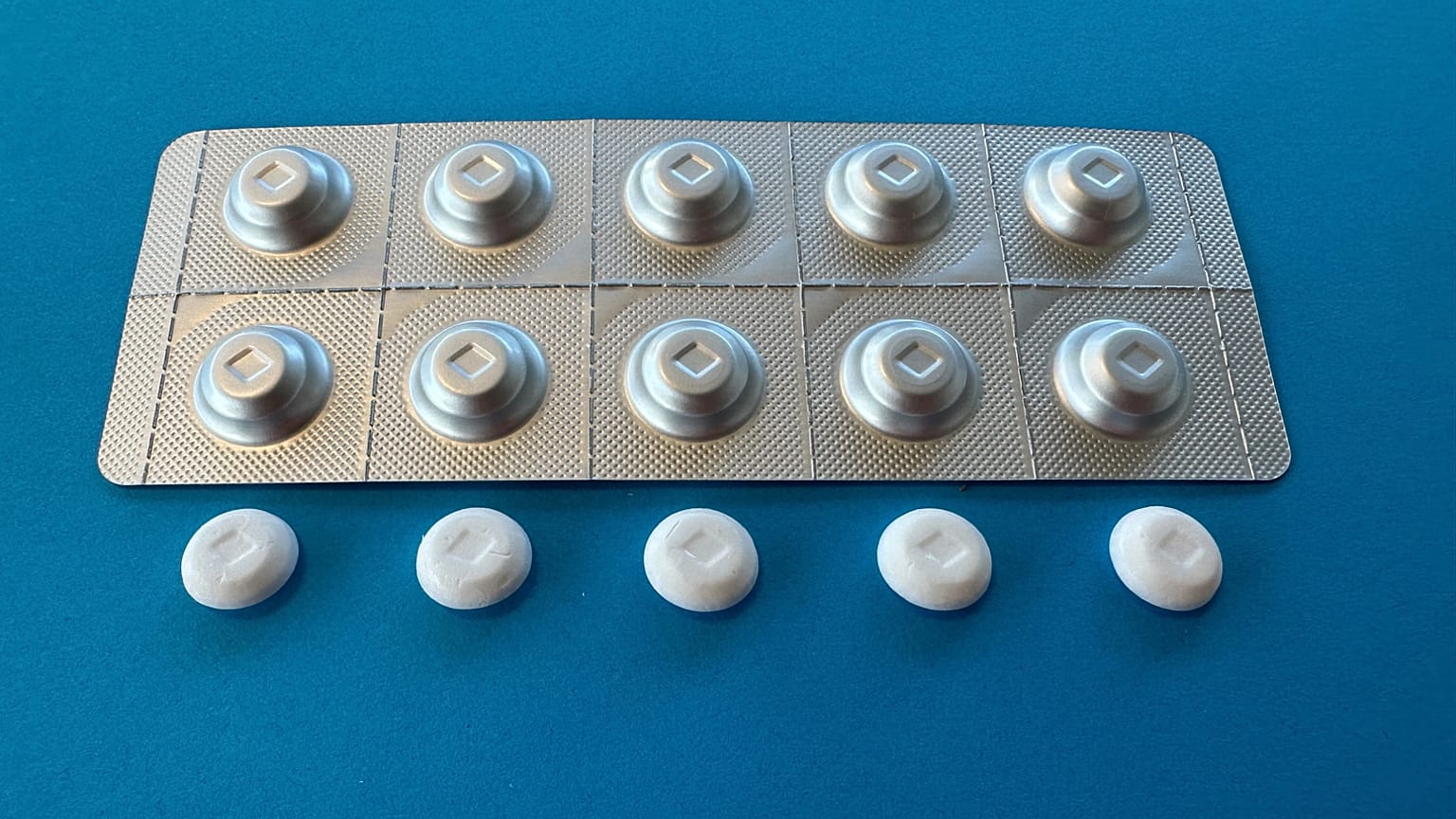

Kamenetz came to the world of psychedelics through his participation in a Johns Hopkins-New York University study in which clergy of various faiths took doses of psilocybin, the compound found in hallucinatory mushrooms, to test how spiritually attuned people would respond. While the study itself has generated as much controversy as firm results, it has fostered the launch of at least two other organizations touting its work.

On a hot August night in 2019, Kamenetz, then a director of San Francisco’s Jewish Community Center, stood in the back of a crowded Judaica shop in Berkeley to describe two psilocybin trips he experienced on separate “dose days” during the study. On the first occasion, he saw a vision of the kabbalistic Tree of Life, a diagram central to Jewish mysticism; on the second, he encountered a dark void. “Yes, there is the bliss and color and light, but then there’s a higher reality that falls away to experiencing the void,” Kamenetz said, according to The Jewish News of Northern California.

Kamenetz’s inbox quickly filled with inquiries from people looking to discuss their psychedelic experiences. Months later, as the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a global shutdown and Kamenetz subsequently lost his job at the JCC in the summer of 2020, he saw it as an opportunity to innovate.

At first, Shefa, which in Hebrew means “flowing abundance,” began as a series of Zoom-based integration circles open to Jews across the spectrum of observance. The meetings incorporated short teachings based on the Jewish calendar or weekly Torah reading, and participants shared about previous psychedelic trips.

Shefa began publishing newsletters, hosting courses and in-person events across the country. The point, according to Kamenetz, was not to encourage illegal drug use — a disclaimer on Shefa’s website says: “We do not conduct illegal activities, nor do we refer people toward illegal activity. We also do not provide mental or medical healthcare.” Rather, Kamenetz suggests that adopting a “psychedelic theology” can impact daily life by informing how people understand things such as their interconnectedness with creation or attunement to God’s presence.

A Shefa sticker that says “Judaism Is Psychedelic.” (Courtesy photo)

Shefa attracts Jews from some unexpected corners. “It’s not that I didn’t want to connect to God,” said one person who was raised in ultra-Orthodox Judaism in Brooklyn, who asked to remain anonymous. “It’s just that it didn’t feel like the ultra-Orthodox community was a good fit for where I was at that juncture. When I found psychedelics and specifically Shefa, it was like coming home.”

Kamenetz’s approach reframed his understanding of Judaism, the Brooklynite said: Rather than a system of laws, he now sees Judaism as “a path towards an intimate and transformative connection with God.”

Shefa’s events initially provided only education about psychedelics and Judaism, without involving psychedelics directly. But after Hamas’ attacks on Oct. 7, 2023, Kamenetz, who had trained in ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, began facilitating retreats in Berkeley with the drug, a powerful anesthetic with hallucinogenic effects.

Participants were required to complete a long application and medical screenings before meeting online to prepare in sessions that drew on Hasidic and kabbalistic teachings. The ketamine retreats themselves incorporate Jewish prayers, rituals and music, including a process invented by the 18th-century mystic Ba’al Shem Tov to navigate expanded states of consciousness.

RELATED: Groundbreaking synagogue lures burned-out techies with digital strategies (and ecstatic dance)

Months after Oct. 7, a 30-something researcher in the Bay Area who asked to be identified only by her first initial, A., first met Kamenetz at a Purim party facilitated by Shefa where the rabbi was handing out “Judaism is psychedelic” stickers.

It was a difficult season for A., who has family in Israel. Suddenly, the artistic and political spaces she inhabited no longer felt safe. Intrigued by Shefa, she signed up for an in-person, nine-week course and, later, a ketamine retreat.

“Judaism is going through a dark night of the soul,” A. told RNS. “People are disagreeing fundamentally about what it means to be Jewish right now, and what our relationship with our ancestral homeland means, or should be, or could be, and also how to be in the world post-Holocaust, when you realize that a lot of that negative sentiment towards Jews is still there. It is an existential crisis.”

Sam Shonkoff. (Courtesy photo)

Her previous psychedelic experiences had taken place alone. Now, they were happening in a community that deeply understood her Jewish context.

RELATED: Episcopal Church removes priest who founded Christian psychedelic society

Sam Shonkoff, a professor of Jewish studies at the Graduate Theological Union, connected Shefa to the legacy of Jewish counterculture, spearheaded by leaders such as Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who experimented with LSD alongside psychedelic advocate Timothy Leary in the early 1960s and later founded the Jewish Renewal Movement.

The Jewish counterculture was typically populated by politically progressive Jews who, anecdotally, gathered for underground psychedelic encounters that “sprinkled in” Jewish melodies and prayers, said Shonkoff. Often, he added, “the most potent Jewish reverberation” happened after the trip, through Jewish interpretation.

Despite this tradition, said Shonkoff, “it’s another thing to have a 501(c)(3) that has its explicit purpose to really nourish this integration of Jewish tradition and psychedelics, and to have that be aboveground now for half a decade.”

Some researchers caution that approaching Judaism through psychedelics may dilute the power of the faith, but Shefa hasn’t faced much pushback from establishment Jewish leaders. A Christian group called Ligare, by contrast, has faced significant hurdles.

Founded by another participant in the Hopkins-NYU trial, Ligare aims to help individuals process psychedelic experiences from a Christian worldview. A former Ligare intern has criticized its founder, a former Episcopal priest named Hunt Priest, warning that framing psychedelic trips in religious terms could harm the spirituality of those who have a bad experience. Priest’s enthusiasm for psychedelics also drew an investigation from Episcopal leaders, and earlier this year, Priest agreed to be removed from ordination in his denomination, after the investigation found he’d crossed the line from discussing psychedelics into endorsing them.

A third group inspired by the Hopkins-NYU study and Islam, called Ruhani, is in development.

These groups are hardly the first to fuse psychedelics and spirituality; Indigenous Americans have long fought to protect their right to spiritual practices involving peyote and other compounds, and laid the legal groundwork for psychedelic churches that claim psychedelics as sacraments normative to their religious practice.

RELATED: After a decade of controversy, clergy psychedelic study is published

It’s due in part to Indigenous Americans’ ancient ties to psychedelics that Shefa will be hosting its first legal psilocybin retreat this month in Oregon, with both Jewish and Indigenous facilitators. In preparation, the Indigenous facilitators have learned Jewish and Hebrew songs, and the Shefa facilitators are “making space for Indigenous wisdom,” Kamenetz said.

As Shefa develops its psychedelic programming, Hertz said it’s having tangible impacts. He’s attended two Shefa-facilitated ketamine retreats and plans to attend a third; the Jewish framework, he said, has created a comfortable setting where he can be his authentic self. In fact, after a hiatus from the religious expressions of Judaism, he’s recently been inspired to attend Friday night services again.

“Instead of feeling I was living a dual life,” he said, “I now have one life.”

This story was produced with funding from the Templeton Religion Trust.