Handguns are displayed at the Smith & Wesson booth at the Shooting, Hunting and Outdoor Trade Show in Las Vegas. Handguns account for most of the guns being purchased by first-time gun buyers in the United States during the coronavirus pandemic. AP Photo/John Locher

Author

Noah S. Schwartz

April 8, 2020

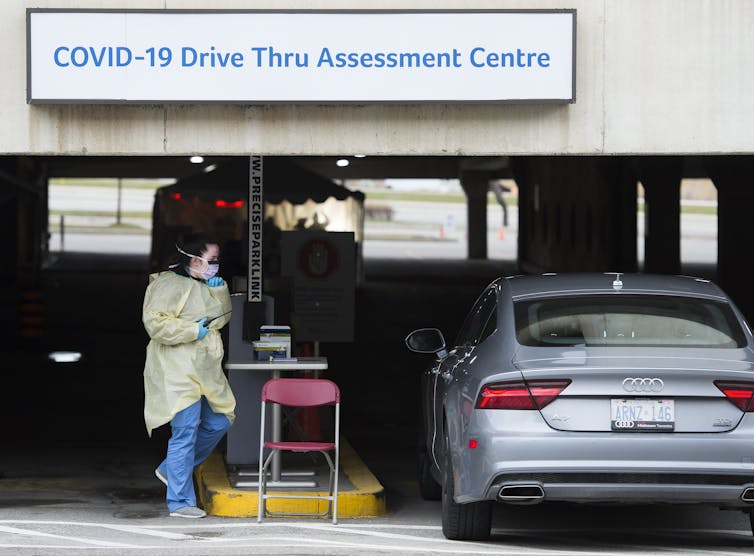

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a surge in gun sales. Estimates based on background checks show that an estimated 2.6 million guns were sold in the United States in March. That is an 85 per cent increase over the same period last year.

While there are no official numbers, gun stores in Canada have also reported increased sales. This has spurred some news media to draw comparisons between the two nations’ gun-sales spikes, potentially stoking the fears of the Canadian public.

This angst has been echoed by gun control groups in Canada that have expressed concerns regarding the impact of “increased access to guns” on public health.

But few have noted the three key differences between the American and Canadian COVID-19 gun-sales spike.

No. 1: Why are they buying?

Canadians and Americans buy guns for different reasons. Over the past few decades, the United States has witnessed a transformation in its civilian gun culture. While in the past, gun ownership was mainly related to hunting and sports shooting, changes in laws and gun advertising have led to a rise in gun ownership for self-defence.

Author

Noah S. Schwartz

April 8, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a surge in gun sales. Estimates based on background checks show that an estimated 2.6 million guns were sold in the United States in March. That is an 85 per cent increase over the same period last year.

While there are no official numbers, gun stores in Canada have also reported increased sales. This has spurred some news media to draw comparisons between the two nations’ gun-sales spikes, potentially stoking the fears of the Canadian public.

This angst has been echoed by gun control groups in Canada that have expressed concerns regarding the impact of “increased access to guns” on public health.

But few have noted the three key differences between the American and Canadian COVID-19 gun-sales spike.

No. 1: Why are they buying?

Canadians and Americans buy guns for different reasons. Over the past few decades, the United States has witnessed a transformation in its civilian gun culture. While in the past, gun ownership was mainly related to hunting and sports shooting, changes in laws and gun advertising have led to a rise in gun ownership for self-defence.

Gun ownership in the United States used to be mostly related to hunting and

sports shooting. (Austin Pacheco/Unsplash)

In the 1970s, only 20 per cent of gun owners indicated self-defence as their primary reason for gun ownership. In the 1990s, following the explosion of laws that allowed Americans to carry guns outside the home, 46 per cent listed self-protection.

More recent studies have shown that 76 per cent of gun owners now report protection as their primary motivation for gun ownership.

The surge in first-time buyers suggests that many Americans buying guns during the pandemic are doing so due to concerns about self-defence, given fears of looting, violence and the government’s capacity to deal with the crisis.

With the absence of a gun-carry movement in Canada, this same shift has not taken place. The conditions under which guns can be used for self-defence in Canada are narrow, and the government stringently regulates not only firearms ownership, but the discourse surrounding guns.

Self-defence is not a legal reason to acquire a firearm in Canada, and cannot be listed as a reason for firearms ownership on a Possession and Acquisition License (PAL) application.

Though no research exists at this time, owners of gun stores who were interviewed by the media noted that Canadians are likely panic-buying due to a fear of shortages rather than a fear of violence, since the Canadian supply chain is heavily dependent on the United States.

That means gun owners who might have waited to buy firearms and ammunition for target shooting over the summer or hunting this fall are buying them now.

No. 2: How are they buying them?

Another key difference between the bump in sales in Canada versus the U.S. is the requirements to purchase guns and ammunition. South of the border, most firearms legislation is made at the state level, with big differences in gun laws across the country.

In many states, the only requirement to purchase a firearm from a licensed dealer is a federal background check, though states like California and Massachusetts have much stricter laws.

In Canada, the bump in sales is limited to those who have already passed through the RCMP’s extensive licensing regime. This process often takes up to six months and includes a weekend-long course, passing a written and practical test and reference checks. Canadian gun owners are subject to continuous automatic background checks as long as they hold the licence.

So if somebody is legally purchasing a gun in Canada, it means the RCMP could find “no reasons why, in the interest of public safety, they should not possess a firearm.”

No. 3: Who is buying what?

Many of the people buying guns in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic reported that it was their first time purchasing a gun. Furthermore, the majority of guns sold during the current boom have been handguns rather than long guns.

Though it’s a bit early to speculate, this could very well lead to even less support for gun control in the U.S., given that gun owners are unsurprisingly the least likely group to support gun control.

In the 1970s, only 20 per cent of gun owners indicated self-defence as their primary reason for gun ownership. In the 1990s, following the explosion of laws that allowed Americans to carry guns outside the home, 46 per cent listed self-protection.

More recent studies have shown that 76 per cent of gun owners now report protection as their primary motivation for gun ownership.

The surge in first-time buyers suggests that many Americans buying guns during the pandemic are doing so due to concerns about self-defence, given fears of looting, violence and the government’s capacity to deal with the crisis.

With the absence of a gun-carry movement in Canada, this same shift has not taken place. The conditions under which guns can be used for self-defence in Canada are narrow, and the government stringently regulates not only firearms ownership, but the discourse surrounding guns.

Self-defence is not a legal reason to acquire a firearm in Canada, and cannot be listed as a reason for firearms ownership on a Possession and Acquisition License (PAL) application.

Though no research exists at this time, owners of gun stores who were interviewed by the media noted that Canadians are likely panic-buying due to a fear of shortages rather than a fear of violence, since the Canadian supply chain is heavily dependent on the United States.

That means gun owners who might have waited to buy firearms and ammunition for target shooting over the summer or hunting this fall are buying them now.

No. 2: How are they buying them?

Another key difference between the bump in sales in Canada versus the U.S. is the requirements to purchase guns and ammunition. South of the border, most firearms legislation is made at the state level, with big differences in gun laws across the country.

In many states, the only requirement to purchase a firearm from a licensed dealer is a federal background check, though states like California and Massachusetts have much stricter laws.

In Canada, the bump in sales is limited to those who have already passed through the RCMP’s extensive licensing regime. This process often takes up to six months and includes a weekend-long course, passing a written and practical test and reference checks. Canadian gun owners are subject to continuous automatic background checks as long as they hold the licence.

So if somebody is legally purchasing a gun in Canada, it means the RCMP could find “no reasons why, in the interest of public safety, they should not possess a firearm.”

No. 3: Who is buying what?

Many of the people buying guns in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic reported that it was their first time purchasing a gun. Furthermore, the majority of guns sold during the current boom have been handguns rather than long guns.

Though it’s a bit early to speculate, this could very well lead to even less support for gun control in the U.S., given that gun owners are unsurprisingly the least likely group to support gun control.

Most first-time gun buyers in the United States during the pandemic

have purchased handguns. (Kenny Luo/Unsplash)

In Canada, on the other hand, it is likely that only a small minority of gun purchases during the Canadian spike were first-time buyers given the time frame required to acquire a firearm licence in Canada.

Statistics on the breakdown of handguns versus long gun purchases during the Canadian pandemic spike don’t exist, but we can guess that most of the new guns purchased in Canada were long guns being used for hunting or sports shooting.

That’s because gun owners wishing to own handguns must have a special Restricted Possession and Acquisition License (RPAL) and maintain a membership at a shooting club, which can cost hundreds of dollars per year and limits handgun ownership to serious target shooters.

Of Canada’s 2.2 million licensed gun owners, only about a quarter have licences that allow them to purchase handguns.

And so it’s clear there are major differences between the gun purchase spikes in Canada and the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. This will hopefully set anxious Canadian minds at ease and let everyone get back to focusing on more pressing problems

In Canada, on the other hand, it is likely that only a small minority of gun purchases during the Canadian spike were first-time buyers given the time frame required to acquire a firearm licence in Canada.

Statistics on the breakdown of handguns versus long gun purchases during the Canadian pandemic spike don’t exist, but we can guess that most of the new guns purchased in Canada were long guns being used for hunting or sports shooting.

That’s because gun owners wishing to own handguns must have a special Restricted Possession and Acquisition License (RPAL) and maintain a membership at a shooting club, which can cost hundreds of dollars per year and limits handgun ownership to serious target shooters.

Of Canada’s 2.2 million licensed gun owners, only about a quarter have licences that allow them to purchase handguns.

And so it’s clear there are major differences between the gun purchase spikes in Canada and the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. This will hopefully set anxious Canadian minds at ease and let everyone get back to focusing on more pressing problems

AUTHOR

Noah S. Schwartz

PhD Candidate, Political Science, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Noah S. Schwartz receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Partners

PhD Candidate, Political Science, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Noah S. Schwartz receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Partners