Learning to Live Diversity in India

Twenty-two-year-old Wendy Doniger of Great Neck, Long Island, NY arrived in Calcutta in August 1963, on a scholarship to study Sanskrit and Bengali.

Wendy Doniger, Githa Hariharan

26 Jun 2022

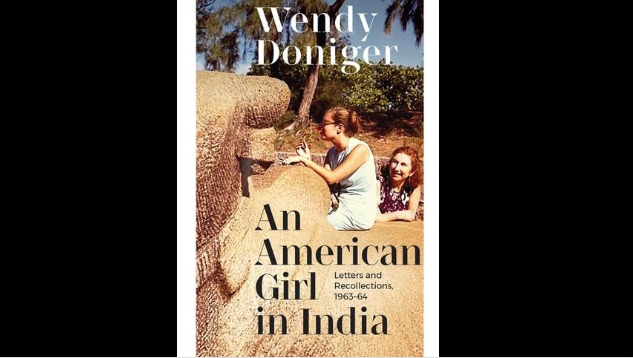

Image courtesy: Speaking Tiger

Twenty-two-year-old Wendy Doniger of Great Neck, Long Island, NY arrived in Calcutta in August 1963, on a scholarship to study Sanskrit and Bengali. It was her first visit to the country whose history and culture she was deeply interested in. Over the coming year—a lot of it spent in Tagore’s Shantiniketan—she would fall completely in love with the place she had till then known only through books.

In An American Girl in India: Letters and Recollections, 1963-64 (Speaking Tiger, 2022), the country comes alive through her vivid prose, introspective yet playful, and her excitement is on full display whether she is writing of the paradoxes of Indian life, the picturesque countryside, the peculiarities of Indian languages, or simply the mechanics of a temple ritual that she doesn’t understand.

In this conversation with Githa Hariharan, Doniger talks about her letters and recollections as well as her journey, from the young girl who wrote those letters to the woman looking back and how in many ways, that journey has also been the journey of what India was and what it has become.

Wendy Doniger | UChicagoNews

Githa Hariharan (GH): Throughout the collection of letters and recollections in An American Girl in India, I had a sense of a ‘prequel’ – in terms of the work you have done, the first loves that have grown deeper, and the books; but also the kind of person you have become. In what ways did travel, specifically travel to a crazily diverse place like India, train you in crossing cultural borders? In being open-minded to ideas as well as experiences?

Wendy Doniger (WD): That first trip to India was indeed the most important educational experience in my life, so much more important than everything I ever learned in universities. The letters betray the constant tension between my passionate love of so many facets of Indian life – the ancient culture, the people I met, the architecture, the music, the food, even the extremes of the climate – and my disappointment in myself for not being able to love everything about India, the poverty, the begging; I never got used to being begged from, especially by women and children. I learned how to go on loving and appreciating all the facets of India – and by extension, eventually, all sorts of other things on the planet earth, and indeed other peoples – despite being painfully aware of many of their tragic shortcomings. In particular, I learned to appreciate all that I loved about Hinduism – its diversity, its great stories, its passions, its architecture, its music – without losing my awareness of its capacity for violence, in animal sacrifices as well as in human conflicts, perhaps, in some ways, always reflecting the violence of the climate.

Also read | An American Girl in India: Letters and Recollections, 1963-64

GH: In the same vein, I think of the trope of travel to other places to understand where you come from, and meeting all kinds of ‘others’ to understand a little more of yourself. This is also underlined by the connections you make, whether it is through films, literature, songs, jokes and proverbs. Did you leave with a different sense of ‘identity’ than you came with? And now, when you read the letters, what are the selves that reveal themselves to you?

WD: I certainly learned, from living in India, how very privileged I had been growing up as I did in America. And I learned, from experiences such as passing out cold when they chopped off the head of the goat in the sacrifice, that any plans I might have had to become an anthropologist had to be abandoned for good. I learned that I really did love the Sanskrit stories best of all, better even than the Bengali stories, and that the reality of India – the fabulous temples and spectacular rivers and mountains, the way people dressed and danced and sang – was even more wonderful than the India that I thought I knew from the texts. When I read the letters now, I am embarrassed by the naivete and arrogance of my young self, particularly about politics, but I am proud of her courage and her determination and the way that she never lost her sense of humour, even in difficult situations.

GH: I was struck by your early discovery that humour is so essential to survive the cross-cultural experience. The element of play makes the weighty – whether matters of myth or language or inscrutable cultural practice – a fairly joyous process of discovery, rather than a series of obstacles to be overcome. The tenor is also brisk, almost racy. Is this optimism, or a case of writing cheerily to one’s parents, or a strategy you learnt early to grapple with ‘big’ ideas and experiences?

WD: I was raised never to lose my sense of humour even (or, in fact, especially) in difficult situations; this was my mother’s way of dealing with life, and it stood me in good stead in India. I still can’t resist the temptation to make a joke, even when I’m writing about fairly serious matters. And so the letters are inevitably light-hearted, as indeed was much of my later serious academic writing. But of course you are right about the need to stay cheerful in reassuring my parents that I was well and happy. And so I did not, for instance, tell them how ill I had become, with both amoebic and bacillary dysentery, or how frightened I was by the angry Hindu mobs attacking Muslims in Calcutta in the first skirmishes of what was to become the war between India and Pakistan in 1965, or, in another sphere, how I had, inadvertently, gotten quite stoned on bhang on the night of Durga Puja in Bengal. Often the best way I found to explain to myself, as much as to my parents, a particularly troubling or puzzling aspect of Indian life, was to find a parallel in a much-retold old family joke.

GH: This has been quite an exercise in looking back, reconstructing, but also judging and forgiving yourself. How self-conscious and deliberate were you in constructing the persona of the past, and the present older persona looking over the girl’s shoulder?

WD: My first reaction to the letters was that I would have to censor a great deal if I was going to publish them. I did, in fact, cut out a lot of boring paragraphs about asking my parents to send me stuff and telling them what I was sending them and so forth. But then I wanted to cut out the stupid things that I had said, the spoilt-brat assumptions as well as blatant errors about Indian history and contemporary Indian politics, and even mistakes in the plots of the myths I recounted. However, my Indian publisher, Ravi Singh, urged me to keep in those uncomfortable, often embarrassing bits, but to write a preface to the book as a whole, and individual prefaces to sections and sometimes to particular letters, noting that I now realize that these were, in fact, mistakes; and, in a way, to forgive my younger self for her ignorance and her naivete, but always to make it clear that I stopped holding those opinions long ago. And I returned again and again, in later years, to many of the myths that had fascinated me even then, now correcting my errors as I read the texts of the stories that I had often just heard people tell when I was in India, and I came to understand more and more of the history that had framed them. So those prefaces did in fact construct what you rightly call an ‘older persona looking over the girl’s shoulder,’ somehow forgiving her for at least being frank about her wrongheaded ideas. In a way, leaving those wrong ideas in the letters and apologizing for them is my answer to the excesses of the cancel culture: yes, we were wrong in the past, and we are not going to go on doing that now, but we need not condemn everything about the way we were then, nor deny it.

GH: You have a deep, almost poetic connection to the landscape – do you continue to have that, and revel in the sensory as you did during your early travels in India?

WD: Never again did I have the chance to immerse myself as deeply in the landscape as I did in those months when I lived in the countryside at Shantiniketan. But on later visits to India, I often spent weeks, if not months, in other parts of India, and always left the cities to travel to the countryside. I particularly recall getting to know the feel of the land when I stayed on the coast of Kerala some years ago, after watching some Koodiyattam performances, and again traveling in the desert outside of Jaipur after speaking at the Jaipur literary festival, and on another occasion traveling in a boat all around Sri Lanka, frequently going ashore for a day or two. And, of course, I never lost my pleasure in immersing myself in Indian music, and Indian art, and Indian stories most of all, even back in America.

Also read | Hindutva, Counter-Culture and Manusmriti

GH: There are so many worlds that co-exist in this slim volume, and you seem to straddle all of them. What is your description of a true cosmopolitan?

WD: I don’t think I was a true cosmopolitan when I arrived in India, though I was certainly open to new ideas and new places right from the start. I remained very much an American in my tastes and many of my habits, but I emerged from that year much more aware of the limits of the American world I had grown up in, and much more appreciative of the sensibilities of people who felt very differently from me about basic aspects of human life. Perhaps that is a working definition of a cosmopolitan.

GH: Inevitably, the India you saw up close then and the India that we are all struggling to understand now: are we in danger of eroding that gloriously multi-stranded, argumentative narrative so characteristic of Indian myth and tale as well as cultural practice?

WD: Certainly the intrusive presence of mass world culture, first in film and then in television and now in the Internet and YouTube and podcasts and all the rest, and particularly as these media are manipulated in the hands of rich, powerful people who know how to use the media to change the opinions and the lives of people at all levels of society – certainly all of this does threaten to erode the India that I saw and loved in the 1960s, a place where geographical variations and caste traditions and village traditions and just the whole polytheistic and polyphilosophical and polyritual nature of Hinduism was still alive and well and living in India, right alongside Islam as well as, to a lesser but still significant extent, Buddhism and Jainism and Christianity and even Judaism. So much of this is under serious attack in India today. But people in India are still telling their stories and publishing their poems and novels and showing their paintings and their sculptures and practicing their family rituals all over the great subcontinent, and that gives me hope.

GH: Finally, a word or two about your first love, Shiva. Did it last? Were there competitors?

WD: Ah, Shiva has always remained the god who seems to me best to express the way the universe really is, as well as being the god who is the subject of the best stories and much of the best sculpture in India. The Shiva of the Puranas, the Shiva of Kailasanatha at Ellora, Shiva with Parvati and Nandi – I still find him fascinating and, though enigmatic, the deity best able to explain to me the nature of reality.

I FIRST CAME ACROSS WD WHEN I READ SOMA, BY WASSON, SHE WAS THE COLLABORATOR AND TRANSLATOR OF RG VEDA THE SANSKRIT REFERENCES TO THE MAGICK MUSHROOM SOMA. WE USED THIS TEXT IN MY SHAMANISM CLASS IN COMPARITIVE RELIGION AT THE UNIV OF ALBERTA I ALSO READ HER WORK ON SHIVA, AS WELL SHE HAS WRITTEN A REVISIONIST HISTORY OF HINDUISM I CANNOT RECCOMEND ENOUGH

by R. Gordon Wasson

Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality, by R. Gordon Wasson (New York, 1968), in 404 bookmarked and searchable pdf pages, with numerous color plates and illustrations. A Wikipedia entry discusses the remarkable work of Wasson, and his identification of the Amanita muscaria (or, fly-agaric) mushroom as a psychoactive component in the mysterious Soma beverage mentioned in the Hindu Vedas. Sanskritist Wendy Doniger is the book's coauthor. Scanned by Robert Bedrosian. Internet Archive has a selection of works about ethnobotany.

Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality, Paperback – April 1 1972 by Robert Gordon Wasson (Author) 11 ratings See all formats and editions Kindle Edition $3.45 Read with Our Free App Hardcover $2,391.99 1 Used from $2,391.99 Paperback $152.65 5 Used from $124.00

https://www.amazon.ca/Soma-Immortality-Robert-Gordon-Wasson/dp/015683…

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21305914

In 1968 R. Gordon Wasson first proposed his groundbreaking theory identifying Soma, the hallucinogenic sacrament of the Vedas, as the Amanita muscaria mushroom. While Wasson's theory has garnered acclaim, it is not without its faults. One omission in Wasson's theory is his failure to explain how pre …