Cave objects suggest modern humans and Neanderthals shared continent for several thousand years

Nicola Davis

Mon 11 May 2020

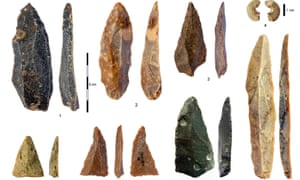

Stone artefacts found at Bacho Kiro cave. Photograph: Tsenka Tsanova/SWNS

Modern humans were present in Europe at least 46,000 years ago, according to new research on objects found in Bulgaria, meaning they overlapped with Neanderthals for far longer than previously thought.

Researchers say remains and tools found at a cave called Bacho Kiro reveal that modern humans and Neanderthals were present at the same time in Europe for several thousand years, giving them ample time for biological and cultural interaction.

“Our work in Bacho Kiro shows there is a time overlap of maybe 8,000 years between the arrival of the first wave of modern humans in eastern Europe and the final extinction of Neanderthals in the far west of Europe,” said Prof Jean-Jacques Hublin, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, a co-author of the research, adding that that was far longer than previously thought. Some scholars have suggested a period of not more than 3,000 years.

Neanderthals were roaming Europe until about 40,000 years ago. “It gives a lot of time for these groups to interact biologically and also culturally and behaviourally,” Hublin added.

Writing in studies published in the journals Nature and Nature Ecology & Evolution, Hublin and colleagues report how they excavated Bacho Kiro, a site that has been studied several times over the past decades. Previous excavations revealed human remains and tools of a very specific type known as “initial upper palaeolithic”. Hublin said such stone and bone tools showed features both of tools known to have been used by Neanderthals and toolkits used by later modern humans, with much debate over which hominin was making them.

However, previous dating of the site ran into a number of difficulties, including from contamination. Now Hublin and colleagues have carried out new excavations and unearthed more tools and remains, including bone fragments and a tooth revealed by methods including ancient DNA analysis to be from early modern humans.

The team report that radiocarbon dating of modern human remains found in the same layer as the tools suggested the remains dated to between 46,790 and 42,810 years ago, while a dating technique based on the rate of changes in DNA from mitochondria, the “powerhouses” of cells, suggested a date of between 44,830 and 42,616 years ago.

The team say the same sort of tools were found in the layer beneath, alongside animal remains dating to almost 47,000 years ago. “We are talking about the oldest modern humans in Europe,” said Hublin, adding that their archaeological context was “crystal clear”. In other words, this group was making initial upper palaeolithic tools .

Among further discoveries, the researchers found jewellery fashioned from cave bear teeth that they say is strikingly similar to that produced by the very last Neanderthals. They say this adds weight to the idea the latter may have adopted innovations as a result of contact with early modern humans.

“Some people would say that is a coincidence; I don’t believe it,” said Hublin, noting there was already genetic evidence that the groups interbred. “I don’t see how you can have biological interaction between groups without any sign of behavioural influence of one on the other.”

Prof Chris Stringer, an expert in human origins from London’s Natural History Museum, said while his team had previously discovered what was possibly an incomplete modern human skull in Greece from more than 200,000 years ago, the new research was important.

“In my view this is the oldest and strongest published evidence for a very early upper palaeolithic presence of Homo sapiens in Europe, several millennia before the Neanderthals disappeared,” he said.

He added that doubt remained about whether Neanderthals were influenced in their jewellery making by early modern humans.

Stringer said the new study highlighted several mysteries, including why the appearance of such early modern humans in Europe 46,000 years ago did not lead to their earlier establishment and an earlier disappearance of Neanderthals.

“One possibility is that the dispersals into Europe [of modern humans of the initial upper palaeolithic] were by pioneering, small bands, who could not sustain their occupations in the face of a larger Neanderthal presence, or the unstable climates of the time,” he said.

Modern humans were present in Europe at least 46,000 years ago, according to new research on objects found in Bulgaria, meaning they overlapped with Neanderthals for far longer than previously thought.

Researchers say remains and tools found at a cave called Bacho Kiro reveal that modern humans and Neanderthals were present at the same time in Europe for several thousand years, giving them ample time for biological and cultural interaction.

“Our work in Bacho Kiro shows there is a time overlap of maybe 8,000 years between the arrival of the first wave of modern humans in eastern Europe and the final extinction of Neanderthals in the far west of Europe,” said Prof Jean-Jacques Hublin, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, a co-author of the research, adding that that was far longer than previously thought. Some scholars have suggested a period of not more than 3,000 years.

Neanderthals were roaming Europe until about 40,000 years ago. “It gives a lot of time for these groups to interact biologically and also culturally and behaviourally,” Hublin added.

Writing in studies published in the journals Nature and Nature Ecology & Evolution, Hublin and colleagues report how they excavated Bacho Kiro, a site that has been studied several times over the past decades. Previous excavations revealed human remains and tools of a very specific type known as “initial upper palaeolithic”. Hublin said such stone and bone tools showed features both of tools known to have been used by Neanderthals and toolkits used by later modern humans, with much debate over which hominin was making them.

However, previous dating of the site ran into a number of difficulties, including from contamination. Now Hublin and colleagues have carried out new excavations and unearthed more tools and remains, including bone fragments and a tooth revealed by methods including ancient DNA analysis to be from early modern humans.

The team report that radiocarbon dating of modern human remains found in the same layer as the tools suggested the remains dated to between 46,790 and 42,810 years ago, while a dating technique based on the rate of changes in DNA from mitochondria, the “powerhouses” of cells, suggested a date of between 44,830 and 42,616 years ago.

The team say the same sort of tools were found in the layer beneath, alongside animal remains dating to almost 47,000 years ago. “We are talking about the oldest modern humans in Europe,” said Hublin, adding that their archaeological context was “crystal clear”. In other words, this group was making initial upper palaeolithic tools .

Among further discoveries, the researchers found jewellery fashioned from cave bear teeth that they say is strikingly similar to that produced by the very last Neanderthals. They say this adds weight to the idea the latter may have adopted innovations as a result of contact with early modern humans.

“Some people would say that is a coincidence; I don’t believe it,” said Hublin, noting there was already genetic evidence that the groups interbred. “I don’t see how you can have biological interaction between groups without any sign of behavioural influence of one on the other.”

Prof Chris Stringer, an expert in human origins from London’s Natural History Museum, said while his team had previously discovered what was possibly an incomplete modern human skull in Greece from more than 200,000 years ago, the new research was important.

“In my view this is the oldest and strongest published evidence for a very early upper palaeolithic presence of Homo sapiens in Europe, several millennia before the Neanderthals disappeared,” he said.

He added that doubt remained about whether Neanderthals were influenced in their jewellery making by early modern humans.

Stringer said the new study highlighted several mysteries, including why the appearance of such early modern humans in Europe 46,000 years ago did not lead to their earlier establishment and an earlier disappearance of Neanderthals.

“One possibility is that the dispersals into Europe [of modern humans of the initial upper palaeolithic] were by pioneering, small bands, who could not sustain their occupations in the face of a larger Neanderthal presence, or the unstable climates of the time,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment