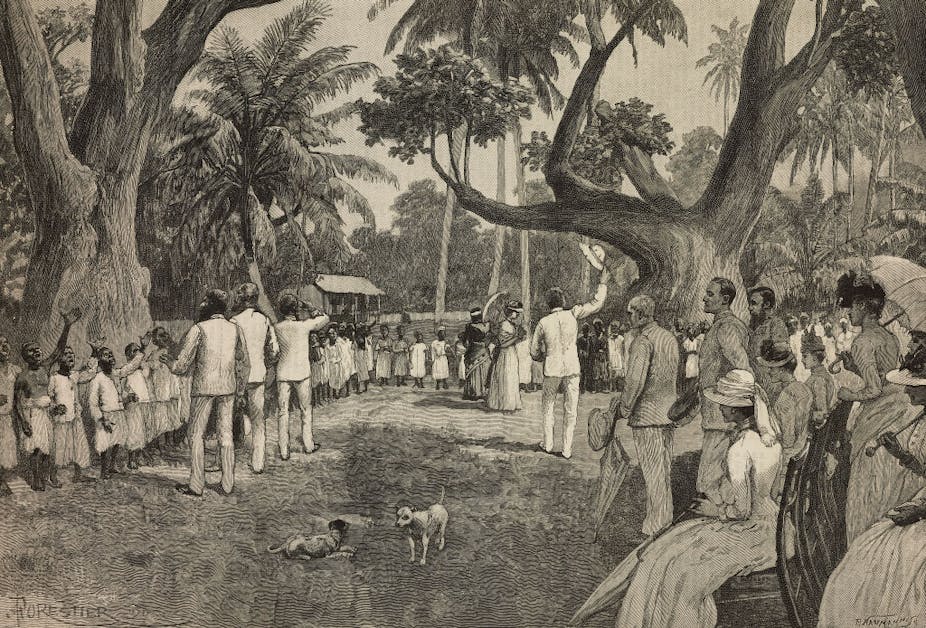

Medical volunteers have been a common sight in African countries like Zambia since the colonial era. Engraving from The Illustrated London News, volume 96, No 2654, March 1, 1890/Getty Images

In the past decade, the work of medical volunteers in Africa has been heavily debated. These volunteers – often from Western Europe and North America – arrive in African countries to work in clinics and hospitals, providing medical treatment for patients in poor urban and rural settings.

Important criticisms have been made of this kind of work. The Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole coined the term “white saviour industrial complex” to describe a sector that does more to affirm the “sentimental needs” of white volunteers than to engage with the political dynamics that sustain inequality and poverty in African countries. Social scientists have also studied the work of international medical volunteers. This research shows that these volunteers often cause harm by undermining the authority of African health professionals or by performing risky clinical procedures.

But important voices are sometimes missing from these debates – particularly those of the people on the receiving end of this “help”.

In the area of rural Zambia where I have been conducting research since 2014, international medical volunteers are a common sight. In my recent research I have considered how people who live in rural Zambia regard these outsiders and make sense of their behaviour. One of the aims of this research is to examine how people in rural Zambia have come to understand the actions of the many medical volunteers who have been arriving in the area since the colonial period.

Written by academics, edited by journalists, backed by evidence.Get newsletter

But to understand how people in rural Zambia perceive these medical volunteers, it is important to observe that such volunteers have been closely associated with several kinds of non-human actors, whose behaviour is worth examining in more detail.

Angels and vampires

Historians and anthropologists have studied how medical interventions by white Europeans – from colonial-era missionary doctors to modern medical researchers – have been perceived by people in African countries in the past. This important work has shown that the presence and behaviour of these outsiders has often produced powerful anxieties and rumours. One of the striking findings of this research is that white medical doctors in central Africa were often identified as “vampires” (banyama). This was because people thought they sought to enrich themselves by extracting their African patients’ blood and vital body substances.

I found in my own research that white medical volunteers in rural Zambia were sometimes associated with vampire rumours. But I also discovered that they were connected to a less malevolent figure: the “angel spirit” or mungelo (bangelo, plural) in Chitonga, the language spoken in southern Zambia.

Traditional healers in the area explained that these spirits visited them and offered them powerful healing advice. One of these traditional healers – a woman I will call Dr Simamba – described the behaviour of these spirits. Arriving at Dr Simamba’s home with a friend, I was shown her shrine. In it, she had placed a tall white feather. This, she explained, was the kind of object that might attract angel spirits who sometimes visited her in person and in dreams.

Dr Simamba could not say for sure why these angel spirits were attracted to white objects. But she thought it might be because these spirits physically resembled white people (bakuwa) and always dressed in white clothing.

Nevertheless, these angel spirits were notoriously difficult to attract:

They come at whatever time they please … sometimes a whole year goes past and nothing!

These spirits were worth waiting for, though. They offered highly effective guidance on how to treat patients. This included advice about which herbs and plants to pick, how to prepare them, and whether to drink them, smoke them or rub them into an incision.

Sometimes angel spirits offered Dr Simamba advice about patients who were already under her care and living within her homestead. On other occasions bangelo offered advice about patients who were going to visit in the future so that Dr Simamba could prepare in advance for their arrival.

I encountered six traditional healers – and was told of many others – who also received visits from spirits. But Dr Simamba’s account also resembles the descriptions of diviners and healers throughout the region. In her work on vernacular healing in Tanzania, the American medical anthropologist Stacey Langwick notes that many people who become healers are “called into relationship with a variety of (new) actors”, including spirits and other non-human actors. And for bangelo diviners, one of the non-human actors with whom they were “called into relationship” was the angel spirit.

Ambivalent actors

Despite the advice they could offer, angel spirits were regarded in morally ambivalent terms. Although they could provide effective advice, they were essentially unpredictable. Diviners struggled to sustain long-term relationships with them.

Much like many of the international medical volunteers whom they physically resembled, these spirits acted according to a logic of their own. They arrived and left when they pleased, without offering a reliable and enduring form of care.

In this sense, both medical volunteers and angel spirits depart from the kind of relationships of care and mutual dependence that people in the region often value highly.

The idea that medical volunteers in Zambia stand outside local relationships – and are therefore not bound by social obligations to Zambians – is one that might explain their association with both vampires and angels. I am not suggesting that these non-human actors are simply metaphoric representations of the “real” white people whom they represent. Rather, I think the behaviour of these human and non-human actors should be considered alongside one another.

The moral attitudes that many people in rural Zambia have towards vampires and angels provide an interesting view – even a critique – of the work of medical volunteers. Perhaps it is time to take these criticisms more seriously and include them in debates about medical volunteering.

In the past decade, the work of medical volunteers in Africa has been heavily debated. These volunteers – often from Western Europe and North America – arrive in African countries to work in clinics and hospitals, providing medical treatment for patients in poor urban and rural settings.

Important criticisms have been made of this kind of work. The Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole coined the term “white saviour industrial complex” to describe a sector that does more to affirm the “sentimental needs” of white volunteers than to engage with the political dynamics that sustain inequality and poverty in African countries. Social scientists have also studied the work of international medical volunteers. This research shows that these volunteers often cause harm by undermining the authority of African health professionals or by performing risky clinical procedures.

But important voices are sometimes missing from these debates – particularly those of the people on the receiving end of this “help”.

In the area of rural Zambia where I have been conducting research since 2014, international medical volunteers are a common sight. In my recent research I have considered how people who live in rural Zambia regard these outsiders and make sense of their behaviour. One of the aims of this research is to examine how people in rural Zambia have come to understand the actions of the many medical volunteers who have been arriving in the area since the colonial period.

Written by academics, edited by journalists, backed by evidence.Get newsletter

But to understand how people in rural Zambia perceive these medical volunteers, it is important to observe that such volunteers have been closely associated with several kinds of non-human actors, whose behaviour is worth examining in more detail.

Angels and vampires

Historians and anthropologists have studied how medical interventions by white Europeans – from colonial-era missionary doctors to modern medical researchers – have been perceived by people in African countries in the past. This important work has shown that the presence and behaviour of these outsiders has often produced powerful anxieties and rumours. One of the striking findings of this research is that white medical doctors in central Africa were often identified as “vampires” (banyama). This was because people thought they sought to enrich themselves by extracting their African patients’ blood and vital body substances.

I found in my own research that white medical volunteers in rural Zambia were sometimes associated with vampire rumours. But I also discovered that they were connected to a less malevolent figure: the “angel spirit” or mungelo (bangelo, plural) in Chitonga, the language spoken in southern Zambia.

Traditional healers in the area explained that these spirits visited them and offered them powerful healing advice. One of these traditional healers – a woman I will call Dr Simamba – described the behaviour of these spirits. Arriving at Dr Simamba’s home with a friend, I was shown her shrine. In it, she had placed a tall white feather. This, she explained, was the kind of object that might attract angel spirits who sometimes visited her in person and in dreams.

Dr Simamba could not say for sure why these angel spirits were attracted to white objects. But she thought it might be because these spirits physically resembled white people (bakuwa) and always dressed in white clothing.

Nevertheless, these angel spirits were notoriously difficult to attract:

They come at whatever time they please … sometimes a whole year goes past and nothing!

These spirits were worth waiting for, though. They offered highly effective guidance on how to treat patients. This included advice about which herbs and plants to pick, how to prepare them, and whether to drink them, smoke them or rub them into an incision.

Sometimes angel spirits offered Dr Simamba advice about patients who were already under her care and living within her homestead. On other occasions bangelo offered advice about patients who were going to visit in the future so that Dr Simamba could prepare in advance for their arrival.

I encountered six traditional healers – and was told of many others – who also received visits from spirits. But Dr Simamba’s account also resembles the descriptions of diviners and healers throughout the region. In her work on vernacular healing in Tanzania, the American medical anthropologist Stacey Langwick notes that many people who become healers are “called into relationship with a variety of (new) actors”, including spirits and other non-human actors. And for bangelo diviners, one of the non-human actors with whom they were “called into relationship” was the angel spirit.

Ambivalent actors

Despite the advice they could offer, angel spirits were regarded in morally ambivalent terms. Although they could provide effective advice, they were essentially unpredictable. Diviners struggled to sustain long-term relationships with them.

Much like many of the international medical volunteers whom they physically resembled, these spirits acted according to a logic of their own. They arrived and left when they pleased, without offering a reliable and enduring form of care.

In this sense, both medical volunteers and angel spirits depart from the kind of relationships of care and mutual dependence that people in the region often value highly.

The idea that medical volunteers in Zambia stand outside local relationships – and are therefore not bound by social obligations to Zambians – is one that might explain their association with both vampires and angels. I am not suggesting that these non-human actors are simply metaphoric representations of the “real” white people whom they represent. Rather, I think the behaviour of these human and non-human actors should be considered alongside one another.

The moral attitudes that many people in rural Zambia have towards vampires and angels provide an interesting view – even a critique – of the work of medical volunteers. Perhaps it is time to take these criticisms more seriously and include them in debates about medical volunteering.

James Wintrup

Research Fellow in Social Anthropology, University of Oslo

Research Fellow in Social Anthropology, University of Oslo

No comments:

Post a Comment