The scientist who unearthed the “wood wide web” calls on governments and green billionaires to meet the climate challenge

By India Bourke

The Environment Interview

17 March 2022

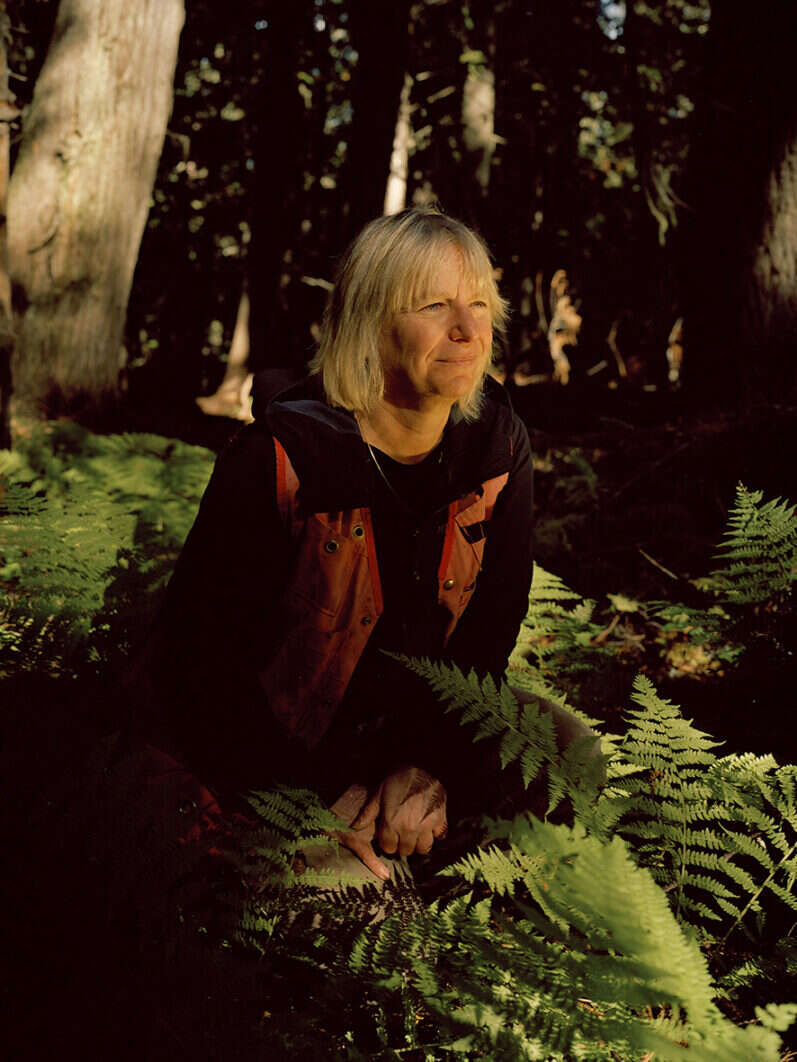

Photo by Brendan George Ko

“Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk: these incredibly wealthy people are making their money off the backs of people, and resources which they are exploiting from the earth. They need to pony up and pay for this,” the world-renowned professor of forest ecology, Suzanne Simard, told me at an outdoor café in St James Park, London. “[They] undermined our government so that they could make cheap s**t. We have to close the circle of responsibility […], we have to hold them to account.”

With her wispy silver hair, piercing birdlike eyes and simple black coat, Simard in many ways conforms to the image of an academic being shepherded around the city on a book tour. But as these passionate outbursts suggest, little about Simard is typical.

Simard’s research has transformed Western understanding of forests, and was the basis for the “tree souls” in James Cameron’s blockbuster movie Avatar. Her work helped unearth the secrets of an underground web of fungi (nick-named the “wood wide web”) that allows trees to communicate and share resources – delivering nutrients and carbon not just within species but between them. Large dominant “mother trees” are also key to these efforts, she has established, helping funnel the network’s support to new seedlings.

[See also: “Austerity is coming back”: Tim Lang fears for food security as war rages]

But while her contributions to science have established that it is collaboration, not competition, that is the governing principle of forest growth, it has been a battle to get there. Even the name “mother tree”, with its anthropomorphising overtones, has sparked controversy: “Everybody was like, ‘don’t do it: it’s going to ruin your career’. And really, the knives do come out.”

Simard is not someone to be easily cowed, however. And working with people from Canada’s indigenous communities helped cement her confidence in her communication style. “Their whole world is about the integration of humans and the nonhuman world; you don’t separate these things at all. In fact, when we do separate them, that’s when we get into so much trouble.”

Her bravery perhaps even runs in her DNA. Raised in the Monashee Mountains of rural Canada, Simard’s gripping memoir Finding The Mother Tree introduces many important figures who populated her youth, from her rodeo-riding brother to her grandfather who rolled logs down rivers at great personal risk. Simard has continued this legacy, helping lead the way for women, first in the logging industry, then science. (Not to mention battling breast cancer, the development of which her research involving toxic herbicides and radioactive isotopes might have contributed).

It is a sweaty, dangerous and highly unique personal story that has captivated creative minds around the world. The author Richard Powers is said to have based his heroine in the award-winning The Overstory on the scientist, while actress Amy Adams is set to star as Simard in an upcoming film adaptation of her memoir.

Yet in light of the evermore dire warnings about the health of the planet, it is not the personal, but the practical and political context of her work that Simard wants to stress. Indeed, she has narrowed her thinking down to a four-point action plan for governments.

[See also: Could Happy the elephant follow an Ecuadorian monkey into legal personhood?]

The “number one” priority should be stemming the source of climate change by decarbonising the energy sector, she explains. Second would be putting a moratorium on deforestation, especially in old growth forests and rainforests, like those in the Amazon, Pacific Rim and Congo. And third should be creating financial mechanisms to ensure that green reforms support people and nature as part of a “well-being economy”.

For too long, she insisted, private companies and corporations have shirked their responsibilities. “They’ve privatised the wealth and socialised the risk,” she explained. “Private wealth has long railed against governments because they don’t want to be taxed.” This has fed a narrative where politicians can’t be trusted, tax is seen as a negative thing and governments are consequently stripped of their resources, she argued. Corporations must “step up and share their wealth, and start funding these life saving measures over the next five years”.

Two much-touted ways of redirecting private finance towards green reform are via carbon-offsetting and carbon taxes. The former involves polluting companies or countries buying “carbon credits” from schemes or nations that are actively absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere, often via planting or protecting forests. The latter charges emitters for each tonne of greenhouse gas emissions they produce. Simard is sceptical about both.

Regarding offsets, the polluter often still continues to pollute, she said, and there’s no guarantee in an age of increasing wildfires, social unrest and poverty, that those forests involved in the schemes are permanent. Similarly with carbon taxes, Simard fears the current carbon price is far too low. It would take thousands of dollars to return this hectare of land back to original forest, she said, looking around at the highly manicured flower beds of St James’ Royal Park. “You’d have to bring in new soil, recreate the landscape, bring in new trees and have people looking after them: it’s expensive.” The price of carbon is at only around $3-$60 a tonne in G20 economies, while analysts estimate it needs to reach at least $100 to meet net zero by 2050.

But if these discrepancies and injustices can be addressed, Simard is hopeful forests – and their wider ecosystems – can respond. The fungal spores that are essential to regeneration can remain in forests for thousands of years, she said, while her research with the Mother Tree Project is exploring how trees from warmer climes can be successfully migrated north as the world heats up. Adapting forestry so that it protects and nurtures mother trees, rather than continuing with today’s clear-cut practices, will be essential to this, she believes.

And that brings us onto her final fourth point for saving the planet: recognising the active role that humans must now play in ecosystem protection. “We need to be moving seeds and species,” she stressed, “because it’s too late for us to let [nature] do it all by itself. We got to return to our original responsibility of caring for Mother Earth.”

Does that mean we are the ultimate “mother tree” I suggested? “Yes.”

Finding the Mother Tree: Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest, by Suzanna Simard. Published in the UK by Penguin.

“Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk: these incredibly wealthy people are making their money off the backs of people, and resources which they are exploiting from the earth. They need to pony up and pay for this,” the world-renowned professor of forest ecology, Suzanne Simard, told me at an outdoor café in St James Park, London. “[They] undermined our government so that they could make cheap s**t. We have to close the circle of responsibility […], we have to hold them to account.”

With her wispy silver hair, piercing birdlike eyes and simple black coat, Simard in many ways conforms to the image of an academic being shepherded around the city on a book tour. But as these passionate outbursts suggest, little about Simard is typical.

Simard’s research has transformed Western understanding of forests, and was the basis for the “tree souls” in James Cameron’s blockbuster movie Avatar. Her work helped unearth the secrets of an underground web of fungi (nick-named the “wood wide web”) that allows trees to communicate and share resources – delivering nutrients and carbon not just within species but between them. Large dominant “mother trees” are also key to these efforts, she has established, helping funnel the network’s support to new seedlings.

[See also: “Austerity is coming back”: Tim Lang fears for food security as war rages]

But while her contributions to science have established that it is collaboration, not competition, that is the governing principle of forest growth, it has been a battle to get there. Even the name “mother tree”, with its anthropomorphising overtones, has sparked controversy: “Everybody was like, ‘don’t do it: it’s going to ruin your career’. And really, the knives do come out.”

Simard is not someone to be easily cowed, however. And working with people from Canada’s indigenous communities helped cement her confidence in her communication style. “Their whole world is about the integration of humans and the nonhuman world; you don’t separate these things at all. In fact, when we do separate them, that’s when we get into so much trouble.”

Her bravery perhaps even runs in her DNA. Raised in the Monashee Mountains of rural Canada, Simard’s gripping memoir Finding The Mother Tree introduces many important figures who populated her youth, from her rodeo-riding brother to her grandfather who rolled logs down rivers at great personal risk. Simard has continued this legacy, helping lead the way for women, first in the logging industry, then science. (Not to mention battling breast cancer, the development of which her research involving toxic herbicides and radioactive isotopes might have contributed).

It is a sweaty, dangerous and highly unique personal story that has captivated creative minds around the world. The author Richard Powers is said to have based his heroine in the award-winning The Overstory on the scientist, while actress Amy Adams is set to star as Simard in an upcoming film adaptation of her memoir.

Yet in light of the evermore dire warnings about the health of the planet, it is not the personal, but the practical and political context of her work that Simard wants to stress. Indeed, she has narrowed her thinking down to a four-point action plan for governments.

[See also: Could Happy the elephant follow an Ecuadorian monkey into legal personhood?]

The “number one” priority should be stemming the source of climate change by decarbonising the energy sector, she explains. Second would be putting a moratorium on deforestation, especially in old growth forests and rainforests, like those in the Amazon, Pacific Rim and Congo. And third should be creating financial mechanisms to ensure that green reforms support people and nature as part of a “well-being economy”.

For too long, she insisted, private companies and corporations have shirked their responsibilities. “They’ve privatised the wealth and socialised the risk,” she explained. “Private wealth has long railed against governments because they don’t want to be taxed.” This has fed a narrative where politicians can’t be trusted, tax is seen as a negative thing and governments are consequently stripped of their resources, she argued. Corporations must “step up and share their wealth, and start funding these life saving measures over the next five years”.

Two much-touted ways of redirecting private finance towards green reform are via carbon-offsetting and carbon taxes. The former involves polluting companies or countries buying “carbon credits” from schemes or nations that are actively absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere, often via planting or protecting forests. The latter charges emitters for each tonne of greenhouse gas emissions they produce. Simard is sceptical about both.

Regarding offsets, the polluter often still continues to pollute, she said, and there’s no guarantee in an age of increasing wildfires, social unrest and poverty, that those forests involved in the schemes are permanent. Similarly with carbon taxes, Simard fears the current carbon price is far too low. It would take thousands of dollars to return this hectare of land back to original forest, she said, looking around at the highly manicured flower beds of St James’ Royal Park. “You’d have to bring in new soil, recreate the landscape, bring in new trees and have people looking after them: it’s expensive.” The price of carbon is at only around $3-$60 a tonne in G20 economies, while analysts estimate it needs to reach at least $100 to meet net zero by 2050.

But if these discrepancies and injustices can be addressed, Simard is hopeful forests – and their wider ecosystems – can respond. The fungal spores that are essential to regeneration can remain in forests for thousands of years, she said, while her research with the Mother Tree Project is exploring how trees from warmer climes can be successfully migrated north as the world heats up. Adapting forestry so that it protects and nurtures mother trees, rather than continuing with today’s clear-cut practices, will be essential to this, she believes.

And that brings us onto her final fourth point for saving the planet: recognising the active role that humans must now play in ecosystem protection. “We need to be moving seeds and species,” she stressed, “because it’s too late for us to let [nature] do it all by itself. We got to return to our original responsibility of caring for Mother Earth.”

Does that mean we are the ultimate “mother tree” I suggested? “Yes.”

Finding the Mother Tree: Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest, by Suzanna Simard. Published in the UK by Penguin.

No comments:

Post a Comment