The war in Ukraine, grain and fertiliser shortages, higher shipping costs and a strong dollar are all pushing food prices up and increasing hunger in dozens of vulnerable countries.

An internally displaced man, who is working as a street food vendor wheels his cart in Sarai Shamali IDP'S camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, October 31, 2021.

Photo: Reuters/Zohra Bensemra/File Photo

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has produced a terrible humanitarian crisis in eastern Europe. It also is worsening conditions for other countries, many of them thousands of miles away.

Together, Russia and Ukraine account for almost 30% of total global exports of wheat, nearly 20% of global exports of corn (maize) and close to 80% of sunflower seed products, including oils. The war has largely shut off grain exports from Ukraine and is affecting Ukrainian farmers’ ability to plant the 2022 crop. Planting there in 2022 is expected to be reduced by nearly a quarter.

Sanctions and constraints on shipping in the Black Sea have largely shut down Russian exports, except by land to neighbouring friendly countries. This is driving up world prices for grain and oilseeds, and increasing the overall cost of food.

Bans on Russian oil have also caused global spikes in energy costs. And both Russia and its ally Belarus, which is affected by some economic sanctions, are major producers and exporters of agricultural fertiliser. High fertiliser prices could have widespread impacts on food production.

I research famines and extreme food security crises and am part of a group of independent experts who review the data, analysis and conclusions whenever a national assessment indicates that a famine may be occurring or about to occur.

The people of Ukraine deserve all of the attention and help that they are receiving. But I believe the global community must not lose sight of humanitarian suffering occurring elsewhere now, including many countries far from the spotlight.

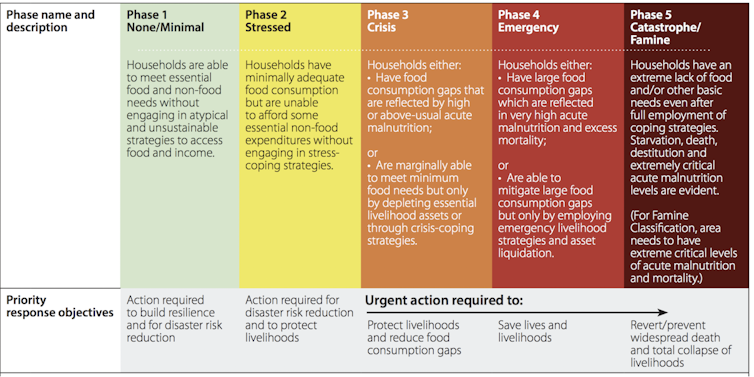

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification measures food insecurity objectively based on a wide range of evidence. Photo: IPC, CC BY-ND

A perfect storm for food scarcity

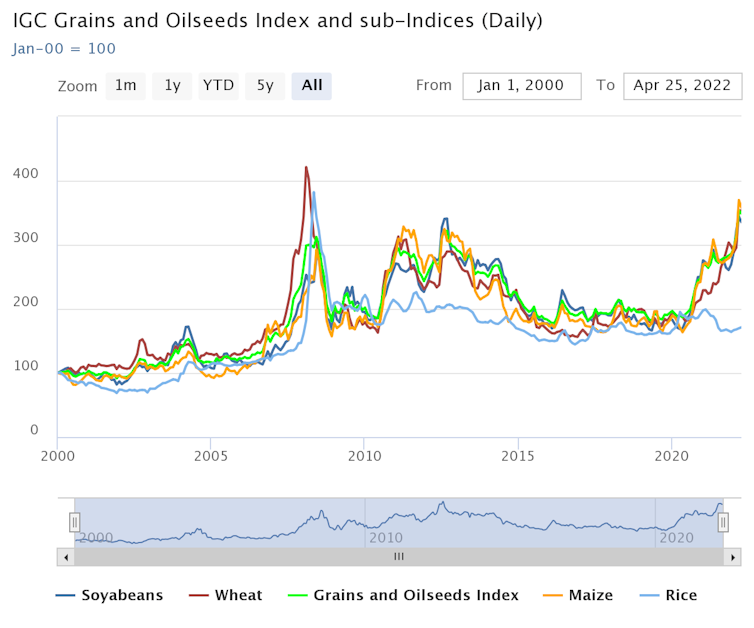

Global food and fertiliser prices were near record highs even before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Prices for grain and oilseed products had already reached or surpassed levels recorded in 2011, when a devastating famine in Somalia – triggered in part by extreme food prices – killed more than 250,000 people.

2011 was also the year of the Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt, Yemen, Libya, Bahrain and Syria. Many factors fuelled those protests, including extraordinarily high bread prices in major Middle East and North African cities.

Now, the war in Ukraine has pushed prices to near all-time highs. As of April 8, the average cost of staple food grains had jumped by more than 17% from February levels. For food-importing countries everywhere, this increase will push the cost of food significantly higher. And with the war likely to continue, a global supply shortfall could lead nations to adopt measures such as export bans that further distort food markets.

The global grain market is very concentrated. More than 85% of global wheat exports come from just seven sources: the European Union, the U.S., Canada, Russia, Australia, Ukraine and Argentina. The same share of maize exports comes from just four countries: the U.S., Argentina, Brazil and Ukraine.

Many nations across the Middle East and North Africa are major wheat importers and buy much of their supply from Russia and Ukraine. For example, Russia and Ukraine provide 90% of Somalia’s wheat imports, 80% of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s, and about 40% each of Yemen’s and Ethiopia’s.

Losing Ukrainian and Russian exports means higher grain prices and much longer shipping distances from alternative suppliers such as Australia, the U.S., Canada and Argentina – at a time when high energy prices are raising shipping costs. And since global grain markets are denominated in U.S. dollars, the dollar’s current strength makes grain even more expensive for countries with weaker currencies.

Famine warning lights

For nations already at risk of famine, these effects could be disastrous. Prior to the war, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation estimated that 161 million people in 42 countries were in extreme food insecurity, meaning they needed urgent food assistance. Over a half-million people faced famine levels of food deprivation – by far the most extreme levels of hunger since at least the early 2000s. The most badly affected countries include Yemen, Ethiopia, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Somalia and Kenya.

The causes of these crises vary. Violent conflict is a common factor across most of them. Some countries are still struggling to recover from the economic and health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. A devastating drought is also affecting the Horn of Africa, with rains from March through May now forecast to be well below average. This would constitute the fourth failed or below-average rainy season in a row for areas of Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya.

Even before the Ukraine invasion, this combination of factors had already led to the highest numbers on record of people needing food and other humanitarian assistance for their survival in the East African Region. Rural labor markets and the price of livestock – the two things that the poorest have to sell – have collapsed due to the drought, precisely as global food prices have spiked. A dramatic decline in purchasing power was a major driver of the 2011 famine in Somalia, and the same circumstances are rapidly taking shape now.

Not enough aid

For countries in crisis, the UN World Food Program is the primary global provider of food for at-risk populations. In 2021, the WFP procured nearly half of its grain from Ukraine.

Much of the WFP’s food aid is delivered as direct cash transfers rather than in-kind supplies. But whatever form it takes, the cost of that aid has increased substantially with rising food, fuel and shipping prices. WFP officials estimate that the cost of its operations has increased by 44% since the start of the war in Ukraine, and the agency now faces a 50% funding gap.

International prices for grains and oilseeds were already high when Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022. Source: Agricultural Market Information System

The crisis in Ukraine has also spotlighted a growing gap between funding and needs, especially in some of the world’s poorest countries. For example, the UN issued a flash appeal for humanitarian assistance to Ukraine in early March 2022. By April 15 it was 65% funded. Countries at risk of famine, whose appeals have been out longer, have received much less funding. On April 15, Afghanistan’s appeal was 13.5% funded; South Sudan, 8.2%; and Somalia only 4.4%. Overall funding for global humanitarian needs stood at 6.5% of requested levels.

When I worked as the deputy regional director for CARE International in East Africa, I often worried about how a humanitarian crisis in one country might have spillover effects in others. There could be influxes of refugees who need assistance, or humanitarian staff might have to be shifted to support the response to the new crisis.

In those days, some crises triggered by drought could affect several countries in the region at once. But the ripple effects from the war in Ukraine could lead to the worsening of humanitarian crises around the world.

Daniel Maxwell is Henry J. Leir Professor in Food Security, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment