Natasha Tusikov, Associate Professor, Criminology, Department of Social Science, York University, Canada

Sun, April 9, 2023

The right to repair means that consumer goods can be fixed and maintained by anyone. (Shutterstock)

On March 28, the Canadian government’s budget announcement introduced a plan to implement a “right to repair” for electronic devices and home appliances in 2024, alongside a new five-year tax credit worth $4.5 billion for Canadian clean tech manufacturers. The federal government will begin consultations on the plan in the summer.

The right to repair allows consumers to repair goods themselves or have them repaired by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) or at independent repair shops. Key elements of the right is that repair manuals, tools, replacement parts and services must be available at competitive prices.

Right-to-repair movements have sprung up in the United States, Europe, South Africa, Australia and Canada, encompassing a range of products. Most familiar might be efforts to allow consumers to choose independent shops to repair their phones and computers.

But the right to repair also involves battles over who should be able to fix Internet of Things devices (all physical objects related to accessing the internet), as well as other products that function via embedded software systems, such as vehicles, agricultural equipment and medical equipment.

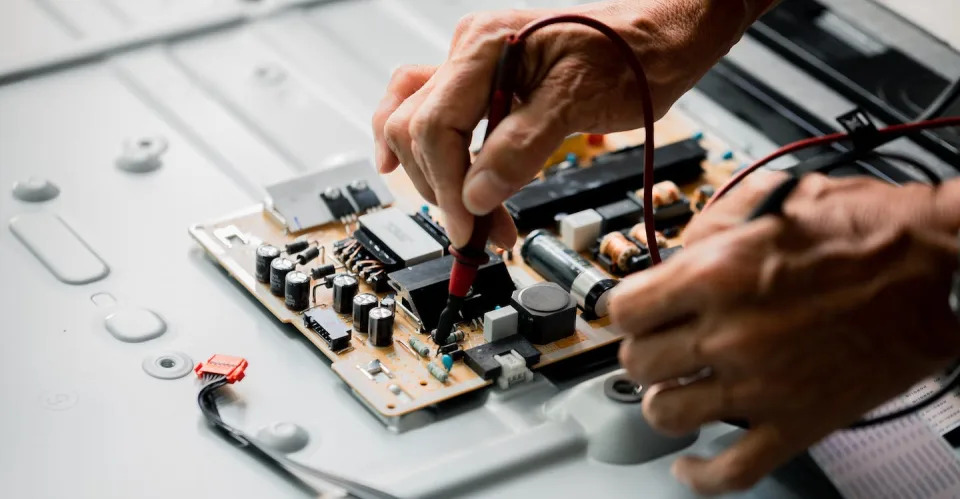

A volunteer repairs a circuit board in Malmo, Sweden, at a fortnightly repair café as part of an international grassroot network calling for the right to repair.

(AP Photo/James Brooks)

Discouraging self-repair

For too long the right to repair has been a casualty of the digital economy. Many manufacturers have long discouraged or outright prohibited independent repair. They do this in part by threatening penalties for copyright infringement or by voiding warranties for products repaired by independent shops or using non-OEM parts.

The corporate power to deny repair is possible because companies that control the digital hearts of software-enabled products can use copyright law to restrict their customers or third-party services from fixing these products. Today, this includes everything from laptops to refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, tractors and fitness wearables.

Identifying problems with software-enabled goods often necessitates the use of diagnostic software, while undertaking repairs often requires copying all or part of the product software. However, manufacturers’ licensing agreements typically prohibit any actions, including repair, that copy or alter the product’s software.

The manufacturers contend that such actions constitute copyright infringement. Companies typically cite this provision to prohibit any repairs undertaken by individuals not licensed by the original manufacturer. Companies may not actually sue customers for copyright infringement, but they may target independent repair shops.

Such tactics may discourage self-repair or the use of independent service people.

Consumer pushback

Questions of who can repair products and under what circumstances are fundamental to the nature of ownership and control. In fact, control over intangible forms of knowledge such as intellectual property and software-enabled goods is central to exerting power in the knowledge economy.

The right-to-repair movement can be understood as a consumer pushback against the commodification of knowledge and a battle over who should be allowed to control and use knowledge — to repair, tinker or innovate — and in whose interests.

Battles over the right to repair have particular relevance for Canada. Major manufacturers, often headquartered in the U.S. or Europe, set rules regarding repair that privilege their business models. These rules favour their branded suppliers and authorized repair technicians to maximize control over repair services.

This not only shuts out Canadian third-party businesses that supply replacement parts and repair services, but also disadvantages Canadian consumers.

Effective policy development

As the Canadian government prepares for consultations on implementing the right to repair, I offer several suggestions:

First, policymakers should build upon right-to-repair efforts elsewhere, particularly Australia, the European Union and the U.S.

Australia appears to be moving toward a right to repair. Its consumer watchdog agency, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, studied the effects of restrictive repair practices on the agricultural machinery and the after-sales market in that country in 2020.

The European Parliament adopted resolutions on the right to repair in 2020 and 2021, and is planning a legislative proposal on the matter by mid-2023, building upon several years of working to make manufacturing and product design more eco-friendly.

In the U.S., President Joe Biden strengthened the case for right to repair in July 2021 with an executive order supporting competition. Recently, attorneys general from 28 states called on lawmakers to advance a right to repair federally.

Second, it’s important to effectively counter industry opposition, which has been successful in defeating right-to-repair legislation. Such legislation continues to face stiff industry opposition at the state level in the U.S.

Big companies in the technology, vehicle and agricultural industries have long lobbied against the right to repair. They argue that repairing or tinkering with their software-enabled products raises potentially serious security and safety complications.

Though such concerns may be valid in some cases (particularly when dealing with safety-critical goods such as medical devices), these are exceptions. In many cases, however, independent repair by appropriately trained technicians can be a safe, viable alternative to manufacturers’ “authorized” repairs.

A right to repair supports the circulation of secondhand goods.

(Jon Tyson/Unsplash)

Third, policymakers should ensure broad engagement with and representation from the people who are most affected by restrictive repair policies. These include small farmers, independent repairers, small retailers of refurbished goods, people who patronize second-hand or reseller stores, and those in the aftermarket industry selling third-party parts.

Input is also needed from people living outside major population centres who must travel to authorized repair shops or otherwise incur costs in time and money in receiving service.

Fourth, it’s time to recognize that the right to repair has benefits beyond consumer rights. Repair bolsters secondary markets, including second-hand stores and resellers that provide their customers with viable used goods, which are important money-savers for economically marginalized communities.

Repair also helps decrease the environmental burden of modern consumerism. This problem is particularly acute in the manufacture of many electronic technologies — once these products no longer function, they are dumped as e-waste, often in developing countries.

Read more: Beyond recycling: solving e-waste problems must include designers and consumers

Finally, policymakers should consider a broad interpretation of the right to repair. This could include requiring manufacturers to make available at competitive prices the necessary items for repair, including diagnostic software and replacement parts. It could restrict manufacturers’ practice of planned obsolescence, that is, letting functional goods be rendered inoperative by withholding essential software updates.

The federal government is offering Canadians a chance to create a right to repair. We should seize the opportunity.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

Third, policymakers should ensure broad engagement with and representation from the people who are most affected by restrictive repair policies. These include small farmers, independent repairers, small retailers of refurbished goods, people who patronize second-hand or reseller stores, and those in the aftermarket industry selling third-party parts.

Input is also needed from people living outside major population centres who must travel to authorized repair shops or otherwise incur costs in time and money in receiving service.

Fourth, it’s time to recognize that the right to repair has benefits beyond consumer rights. Repair bolsters secondary markets, including second-hand stores and resellers that provide their customers with viable used goods, which are important money-savers for economically marginalized communities.

Repair also helps decrease the environmental burden of modern consumerism. This problem is particularly acute in the manufacture of many electronic technologies — once these products no longer function, they are dumped as e-waste, often in developing countries.

Read more: Beyond recycling: solving e-waste problems must include designers and consumers

Finally, policymakers should consider a broad interpretation of the right to repair. This could include requiring manufacturers to make available at competitive prices the necessary items for repair, including diagnostic software and replacement parts. It could restrict manufacturers’ practice of planned obsolescence, that is, letting functional goods be rendered inoperative by withholding essential software updates.

The federal government is offering Canadians a chance to create a right to repair. We should seize the opportunity.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

It was written by: Natasha Tusikov, York University, Canada.

Read more:

Why can’t we fix our own electronic devices?

Families count the costs as big tech fails to offer cheap phone, laptop and fridge repairs

Natasha Tusikov receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She is affiliated with the Centre for International Governance Innovation.

No comments:

Post a Comment