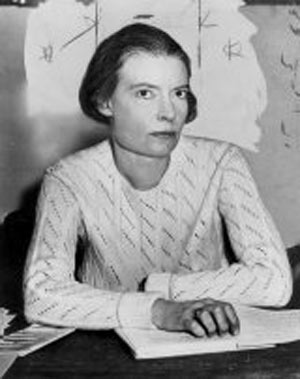

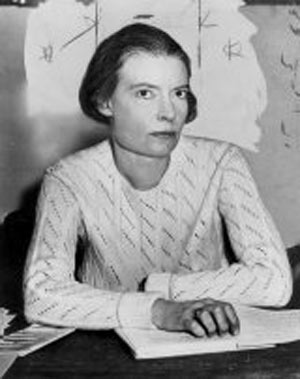

Dorothy Day in 1934. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. Public Domain.

I have a few thoughts in response to what seems like an uptick in interest in Dorothy Day (1897-1980) in recent years. When I first read Dorothy Day, the first thing that stood out to me was her continuity with a long tradition of Christian anarchism in America. Yet as a Catholic, she seemed to represent a split from the main line of Christian anarchism in America, which is distinctly Protestant (though not exclusively so, and who knows how to classify Tolstoy’s religion). In any case, I kept running into her name after years of studying and steeping in the Christian anarchism and non-resistance of folks like Adin Ballou, William Lloyd Garrison, and Henry Clarke Wright, among others. Many of the individualist anarchists received theological instruction and were ordained ministers (for example, Joshua K. Ingalls, William B. Greene). Day resembled these Protestants of the American libertarian tradition in her deep personal commitment and her total rejection of political action, which, as we will discuss, entails explicit renunciation of core features of our political life, for example, voting, paying taxes, and obeying unjust laws. The historian Anne Klejment helps us understand Day’s ideas within this context:

The seedbed of her pacifism extended back into her Protestant young adulthood. Her familiarity with the Bible remained a significant part of her spirituality and informed her pacifism. Back then, the Catholic laity was discouraged from Bible reading. It would take a convert like Dorothy to advance biblical nonviolence as an essential Catholic teaching. She placed enormous emphasis on the commandment to love God and love neighbor. She understood it as the core teaching of Jesus and pondered over it from adolescence until her death.

Many of the American Christian anarchists/non-resistants follow in a long tradition of antinomians, arguably going back to the Antinomian Controversy in New England and before. These episodes left an established tradition of challenging authority and hierarchical power. Day’s Christian anarchism stands out in its delicate location within the Catholic tradition. Indeed, hers was a stance that angered many in both the Church hierarchy and in her old left-wing circles. She recalled at the end of her life that many of her radical friends had felt betrayed by her conversion:

One who had yearned to walk in the footsteps of a Mother Jones and an Emma Goldman seemingly had turned her back on the entire radical movement and sought shelter in that great, corrupt Holy Roman Catholic Church, right hand of the Oppressor, the State, rich and heartless, a traitor to her beginnings, her Founder, etc.

Just as she was a poor fit with the narrow-minded college socialists (more on that below), she was also an awkward fit in a movement defined by people like Proudhon, whom she frequently discussed, and Bakunin. Day’s personalism is another distinctive feature of her approach to anarchism. This is the idea, grounded in a basic belief in the dignity of every human being, that each person must take personal responsibility on every level: that there is a duty to one’s neighbors and coworkers, and we cannot look to others, including large institutions, which are themselves the key offenders and impediments to change. Day often talked about how she was changed after the experience of seeing neighbors come to each other’s aid in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. In an article in 1936, Day explained:

We are Personalists because we believe that man, a person, a creature of body and soul, is greater than the State, of which as an individual he is a part. We are Personalists because we oppose the vesting of all authority in the hands of the state instead of in the hands of Christ the King. We are Personalists because we believe in free will, and not in the economic determinism of the Communist philosophy.

Remarking on the 1927 murder of Italian immigrants and anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Day noted that anarchism “is the word, or label, which confuses many of our readers (especially the bishops?)” Day saw anarchism, as a philosophy of mutual respect and voluntary cooperation, as a natural extension of Christian spiritual practice and fellowship. She argued that there is no human law applicable to those who love and follow Jesus, and that “anarchism means ‘Love God, and do as you will.’” From the moment it became aware of the Catholic Worker movement, the U.S. government has treated it with suspicion, targeting and spying on Day and the movement as supposedly subversive elements. Day’s activism drew the attention of the FBI, and she is said to have enjoyed reading her FBI files.

Day had joined the Socialist Party in Urbana, Illinois, as a teenage college student, but its “petty bourgeois” attitudes and lack of “the religious enthusiasm for the poor” left her cold. She was not one for posturing; her Christian anarchism was based on the idea that every person is “known and named,” and that the real movement for human freedom takes place where there is a human need to be satisfied. Day roundly rejected the value system and approach of rigid bureaucracies and hierarchies, either corporate or governmental, which treat people as case numbers within cold, detached systems of power. As Michael Kazin put it: “Like any good anarchist, Christian or not, Day had no faith whatsoever in the desire or ability of governing authorities to create a moral, egalitarian society.” Her political outlook was grounded in and expressed through the sharing of everyday acts of kindness, through up-close relationships rather than philosophical abstractions. Yet she was extremely well-read and capable of the most insightful and skillfully articulated engagements with advanced ideas. Day has a very particular way with words. There is a rare candor, which reflects her lack of pretenses and her vulnerability in sharing her full life in the most open and sincere way. Her columns go back and forth between the tragedy and the comedy of being human with real thought and skill. Some of the vignettes in her autobiography are as powerful and moving as anything written by any American, for my money. “In 2012, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops unanimously voiced its support for her sainthood,” and this cause is, as I understand it, pending. An anarchist Catholic saint would be something to see.

Rose Hill Catholic Worker farm, Tivoli, New York. Photo: National Park Service.

Day believed that we have the social and political question backwards, starting with abstractions, ideological camps, and grand plans, when what we should focus on what is personal and tangible, what can be done directly, immediately, and without “professional” intermediaries. I was drawn to Day’s writings first because her way of thinking about political and social questions is so categorically different from the one we get from both halves of the poisonous main currents of our discourse today. She rejected both versions of bloodthirsty twentieth century authoritarianism, capitalism and socialism, instead articulating a radical politics of the corporeal and close by. Nothing more complicated in policy terms than housing and feeding our neighbors, the most important work (we prefer conceptual complexity and institutional paralysis while oligarchs bleed the country). Her belief in the transformative power of community and hospitality at the most basic but most intimate scale led her to reject the way almost everyone of our age thinks about politics. Day’s politics were about love for and service to other people; her way of looking at the world, according to her granddaughter, focused on the idea that “what we can do is so little, but that is what we are given to do. That’s only what we can do, so let’s move forward and do what we each think that we can do.” She emphasized “the necessity of smallness,” encouraging a direct and hands-on approach to serving those in need. She could not accept any approach to activism or ministry that separated the theorizing from the doing. Contrast our culture of aloof contempt for the poor, workers, prisoners, migrants and refugees, etc. There is nothing lower than not having money in our anti-human culture and political system. It is thoroughly bipartisan and it will outlast every politician and political party. Rest assured that the state’s indifference toward the suffering of the poor will be there still when there is no more U.S. government.

In Day’s view, we are depriving ourselves of another political dimension in the notion that love is the only response to political moments like this one. Regardless of anyone’s opinions, if love and community are not reliable for us in the social and community context, then what are we talking about? If they aren’t starting with the people at the bottom, what are they building? Everyone seems to feel that the country is lost today. My suggestion is: do not try to find it. Dorothy Day’s example suggests that we find each other, face-to-face, and begin to relearn the lessons of solidarity and mutual aid. We do that and we don’t have to fuss with any of today’s counterfeit B.S. In the social reality that capital and the state are hawking, there is nothing for workers or the poor, nothing but getting shorted. Day saw the crises unfolding around her in terms of human suffering. She did not put herself in the position of judging or condemning; she did not hold out false solutions or panaceas. She asked people to follow her lead in taking personal responsibility and initiative. Among the goals of the House of Hospitality, she stated, was to “emphasize personal action, personal responsibility as opposed to political action and state responsibility.” As a social model, the House of Hospitality explicitly resists impersonal, bureaucratized forms of charity and deliberately puts givers and recipients on the same footing, creating genuine relationships and community life. Day lived a life of voluntary poverty and thought that one should try to “be close enough to people so that you are indifferent to the material.” Central to her thought was leading by example and in accordance with love for all people. Her life, her work, her politics, all inseparable, were based on the radical notion that Jesus meant what he said about loving each other, turning the other cheek, etc.

Day offers another way of thinking about what it means to be politically active within a broader network of movements for freedom, equality, and justice. We don’t need to play to the strengths of the ruling class by focusing our energies and resources back into the sources of hierarchy and domination. Day thought that we had things backwards when it came to political and social change: that is, she believed we are already where the action is, in that everything grows from the bottom up. The movement is where you are, and it exists within your power to take care of people in need. So this is obviously a way of thinking poles apart from the performative nonsense that is encouraged today. Her worldview was a wholesale rejection of today’s faux meritocracy and its ugly pretense that some people are worth more than others. She believed that there is a “a spirit of non-violence and brotherhood” in the Gospels that counsels anarchism in practice. She favored radical decentralization and recognized the principle of subsidiarity, or the idea that decision-making should take place at the most local possible level. In the United States, we have departed from this principle to our own peril, yet neither of our teams seem to understand the problem. Day did not mince words in providing a classically anarchist condemnation of government:

Eventually, there will be this withering away of the State. Why put it off in some far distant utopia? Why not begin right now and say that the state is the enemy. The state is the armed forces. The state is bound to be a tyrant, a dictatorship. A Dictatorship of the Proletariat becomes yet another dictatorship. (emphasis in original)

Day did not believe that we can effectively resist this system of poverty and social alienation by supporting politicians or by mimicking the coercive, bureaucratic style of elites. For her, it could not be a matter of voting, giving alms, or being a good member of some party. Day’s approach represents the opposite of the institutional distance and stuck-up elitism that characterize most of our systems. Day insisted on being there on the ground, sharing daily life in real human connections, resisting the state and consumerism through friendship and love rather than through government. This mode of politics can only be understood and practiced by one who is not interested in being there for others, not in her own opinions or in electing certain politicians, etc. This is the real revolution everyone has been talking about and waiting for, but Day’s isn’t a path most people are capable of walking. One of the mottos of the Catholic Worker movement is, “Conscience is supreme.” Day could not reconcile any politics of division or violence with her own conscience. Institutions that rely on violence – the state, for instance – could not help except by receding into the background; they are not there to help, but rather to create the conditions for widespread deprivation and poverty.

There may be no starker contrast to the hollow identitarian blather of our moment than the life and work of Dorothy Day. Today’s hideous and embarrassing elite-worship, its obsessions with maximums of speed and scale regardless of the social dangers or consequences, its institutional detachment and opacity, and its counterproductive GDPism all represent pervasive social decay and alienation within Day’s philosophy. They are not the visible signs of “progress.” By comparison, today’s PMC liberals appear to be deliberately authoritarian and parochial defenders of plutocracy. And our conservatives, particularly the churchgoing ones, seem to genuinely hate the people Day said we’re commanded to love. I think Professor Larry Chapp put it well, discussing the importance of Day’s politics of resistance to our current moment (now retired, Professor Chapp runs the Dorothy Day Catholic Worker Farm in Pennsylvania):

This is all modern Liberalism has to offer: blunt force and wealth. And what moral and spiritual weapons do we have that are not undermined by our own supreme hypocrisy? We all, rightly, recoil in horror at the sufferings inflicted by Putin’s insane military gambit to restore empire. But empire building is what Liberals do, and have done now for centuries, and so the moral condemnations of our political class rings hollow.

Day didn’t think it was all that difficult to see why our political culture and discourse continue to fail us, particularly those at the margins of our society. Political ideology totally abstracted from the real relations of ministering to the needs of the poor, from the real struggles of workers striving around the clock yet no further from the edges of social and economic oblivion. That is American liberalism today. The American right meanwhile offers an incoherent, unwholesome slop of racial and ethnic scapegoating, open thuggery and corruption, and in MAGA the treatment of the country as a cheap and trashy brand name for enriching the political mercenaries and shady billionaires around Donald Trump. But, fundamentally, the teams share a value system, and the poor are despised by that system. If they’re not blaming them for crime and social discord, politicians are trying desperately to ignore the poor and pretend they don’t exist. This is one of the bedrock values of our system, at least as it exists materially rather than in the purely imaginary fantasies of a PMC that proudly embeds itself in the military-industrial complex even as it scolds everyone.

Statists and imperialists of all kinds, including liberals, who try to appropriate Day should understand that she was not joking about anarchism and would not willingly cooperate with the government; her identity as an anarchist was inseparable from the rest of her life and work, which meant ignoring the law and living according to the law of conscience. Like many anarchists before and since, Day had run-ins with the law throughout her life. She was jailed several times, beginning in 1917, when she was arrested while picketing as part of the Silent Sentinels campaign. She was a fixture of the anti-war and anti-nuclear movements and was jailed several times in the 1950s for her refusal to take shelter during civil defense drills during that period (this protest seems to have been the brainchild of Ammon Hennacy, whom I discussed for the Cato Institute’s Libertarianism.org several years back). Responding to the nuclear mass murders in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Day wrote with rare moral clarity against the death cult that still has our ruling class in its grip:

Jubilate Deo. We have killed 318,000 Japanese.

That is, we hope we have killed them, the Associated Press, on page one, column one of the Herald Tribune, says. The effect is hoped for, not known. It is to be hoped they are vaporized, our Japanese brothers – scattered, men, women and babies, to the four winds, over the seven seas. Perhaps we will breathe their dust into our nostrils, feel them in the fog of New York on our faces, feel them in the rain on the hills of Easton.

Jubilate Deo. President Truman was jubilant.

Day felt the truth in her bones. She understood that those dead families in Japan were our family – they were not evil foreigners. She protested through two world wars and saw firsthand every trick used by the state to stir up hatred and enthusiasm for war. Consider the attitudes of our putatively liberal elite on questions of war and empire today, and contrast them to those of Dorothy Day. Our corporate uniparty has two openly war-mongering and imperialistic wings, with differences only in emphases and vibes, and even there the degree of difference is smaller than is generally thought (respectable opinion in the District wants war, but with Russia and China, not Venezuela). Today, people who have made their entire careers pitching and overseeing disastrous wars of choice get in line for fancy fellowships and interviews on the supposedly progressive shows. Because the U.S. government manages a powerful empire, our political class is compelled by the agglomeration of interests around them to chaperone a politics of imperialism, with disagreement confined to the margins. Higher defense spending is popular with politicians of both parties, because war is the business the state is in. Violence is its key offering in economic terms, much as any lesser mafia. Virtually all members of Congress make their peace with it in one way or another, because this is what the overall system requires of them, and the system is very good at getting what it needs; whatever their reasons, both parties want and actively search for and recruit candidates that they know will be reliably pro-war, often those with connections to the Pentagon or the intelligence community, the major “defense” contractors of the federal government, or financial interests aligned with warfare and empire. Recall that the deepest and strongest connections between the two ways our ruling class shows itself, the state and capital, take place within the world of war. In our system, both always want war because they see it as a source of growth, but they were fused together even before the growth logic took over completely. That is the perversity of our system, which Day saw. She didn’t think one could escape complicity merely because they were positioned within bourgeois polite society; she called the scientists who worked on the bomb murderers, and she demanded accountability from the places of higher learning that allied themselves with “this colossal slaughter of the innocents.” To understand the perversity and degeneration of our politics and discourse, we just have to look at how quickly our simulacra of political participation set up a new enemy of the week, reincorporating the old enemies (e.g., the rehabilitation of George W. Bush) and using the energy and appearance of conflict to reaffirm the imperial system itself. Day understood that the state was a den of thieves and criminals regardless of who is in charge, and the source of positive social change has to be us, working together.

Dorothy Day was an amazing person and a true rarity. She relentlessly downplayed her own importance and contributions to the Catholic Worker movement. During an interview in 1971, a week before her 74th birthday, Day discussed the movement’s humble beginnings and reiterated the centrality of small, personal scale and the face-to-face community to the mission:

You start in with a table full of people and pretty soon you have a line and pretty soon you’re living with some of them in a house. You do what you can. God forbid we should have great institutions. The thing is to have many small centers. The ideal is community.

Not long after, reminiscing at the age of 75, she referred to herself as “the housekeeper of the Catholic Worker movement.” It wasn’t the fake humility of today’s political tabloid show. To her, that work is as worthwhile and honorable as any honest service to other people. She passed away in 1980 at the Catholic Worker’s Maryhouse on the Lower East Side. She was 83. If radicals today are looking for a normative model or a plan of action, the life of Dorothy Day, the first hippie, in Abbie Hoffman’s words, will at least provide inspiration. Growing interest in Dorothy Day must not obscure the central facts of her anarchist politics, that the work to which she dedicated her life can’t ever be carried out by the authoritarian, bureaucratic state or by the professional-managerial class administering it. Her commitments were not those of our political class, and she was explicit about that. They point to forms of personal responsibility and solidarity that are structurally incompatible with the state and capitalism. To take her political ethic seriously is to move in a direction directly opposed to the logic and practices of both mainstream and elite politics today.