Today, some historians classify her belief system as a form of libertarian socialism.

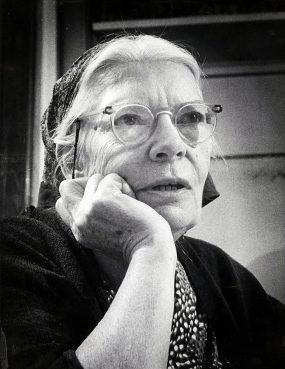

Dorothy Day is one of the most prominent Catholic Social Justice figures. Even in death, she has been profoundly influential among Catholic activists.

Dec 14, 2024 • By Rachel Knight, BA Theology/International Relations

Dorothy Day lived nontraditionally for a Catholic, yet she has a profound influence on many Catholics today. She is even being considered for canonization. She founded the Catholic Worker Movement, including the “hospitality houses” that serve as purposeful communities.

Catholic Social Justice

In order to understand Dorothy Day, it is necessary to first have a brief primer on Catholic Social Justice. Catholic Social Teaching is a canonical set of beliefs about social issues. The modern history of Catholic Social Teaching began in 1891 with the publication of Rerum Novarum, written by Pope Leo XIII. This papal encyclical (a letter written by a pope) responded to problems caused by the Industrial Revolution. Common themes of Catholic Social Teaching are caring for the environment, somewhat left-leaning economic views, caring for the poor, and pacifism. Catholic Social Justice is simply Catholic Social Teaching put into practice.

Whereas the clergy are primarily responsible for coming up with the theological reasoning behind the church’s social teachings, laypeople—Catholics who are not priests—are usually the ones who channel these beliefs into action. This may include protesting, supporting certain policies, setting up charities and programs to help the less fortunate, and exemplifying Catholic Social Teaching principles in their everyday lives.

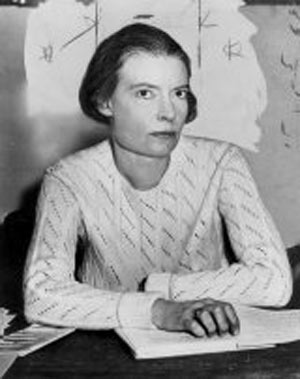

Pre-Catholicism Dorothy Day

Day’s road to becoming a Catholic was a long one. She was born on November 8, 1897, in New York City. She became a journalist, a vocation she would continue for her entire adult life. She was raised in an atheistic household. Despite this, she was interested in theology from an early age. She even convinced her parents to let her be baptized into the Episcopalian faith as a preteen. Still, she did not commit to any religion long-term, as she was always busy furthering social causes. In the end, she synthesized her anarchism, Catholic Social Teaching, and even aspects of communism to form a mission plan and change the world.

Journey to Faith

Day was arrested for protesting on several occasions throughout her life. One incarceration in particular helped kindle a spark that would eventually lead to her conversion. Day was arrested for participating in a suffragist protest outside of the White House in 1917. “Suffragist” refers to people (typically women) who demanded that the US government allow women to vote. Back in 1917, there was no federal law allowing women to vote in elections.

Day practiced a political strategy known as civil disobedience. Civil disobedience is most famous for being the preferred method of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and many (perhaps most) other civil rights movement activists. It essentially means that protesters do not comply with the police, but do not resort to violence, either. Civil disobedience comes with the risk of arrest.

This particular incarceration was much harder on Day than her other stints in jail. The suffragists were tortured, force-fed, and made to live in inhumane conditions. Day was in solitary confinement for long periods of time. Her only respite was the Bible in her cell.

As the years went on, Day had positive experiences attending Catholic churches. She also met Catholic intellectuals who helped inform her personal approach to social justice. Praying the rosary helped her find peace during tumultuous times in her life.

Dorothy Day’s Conversion

Dorothy Day baptized her only daughter into the Catholic Church before she herself became a Catholic. That was in July of 1927. Day was not far behind, however; she converted to Catholicism in December of 1928. One may think, why did she wait so long to convert? Perhaps her political beliefs had been holding her back.

As an activist for social justice, she naturally crossed paths with communist activists. Day associated with communists her entire life, and shared some beliefs with them. However, Catholicism is staunchly against state communism. The main reason for this is that Catholicism considers private property to be a right. Communism is often anti-religion as well. Day was passionate about workers’ rights, much like the communists. She even felt frustrated that she could not participate in the movement due to her religion.

“The Communist Party cared about the welfare of the poor but was unequivocal in its opposition to religion…[Day] asked the elderly Spanish priest at the small church that she attended during the winter months in Manhattan, Our Lady of Guadalupe on West 14th Street, about this troubling dichotomy. Father Zachary Saint-Martin’s counsel was reassuring. ‘Keep your job,’ he told her. [Day was employed as a communist paper at one time.] ‘You have a child to support. That must be your priority, and if your faith is strong enough, there is no need to worry about anything else.’”

Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century, by John Loughery and Blythe Randolph

Collaborations With Peter Maurin

Day met Peter Maurin in December of 1932. This meeting was fortuitous. Maurin taught Day about Catholic Social Justice and she in turn was able to continue her activism in a manner conducive to her Catholicism.

Their beliefs meshed well together. Day and Maurin could be described as soulmates, but without the romance. Together they started a newspaper called The Catholic Worker. To this day, an issue of The Catholic Worker only costs one cent. The title is a play on The Daily Worker, a communist newspaper. The Catholic Social Justice activists and communist activists would engage in light ribbing as they each hawked their periodicals in the streets.

The Catholic Worker was partially made up of articles that expressed Day’s views on Catholic Social Justice. She wrote much of the paper, but others contributed as well. Gradually, a movement began to form. This was called the Catholic Worker Movement.

“The aim of the Catholic Worker movement is to live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus Christ. Our sources are the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures as handed down in the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, with our inspiration coming from the lives of the saints, ‘men and women outstanding in holiness, living witnesses to Your unchanging love.’ When we examine our society, which is generally called capitalist (because of its methods of producing and controlling wealth)…we find it far from God’s justice.”

The Catholic Worker, May 2019 issue

The Catholic Worker Movement

The purpose of the Catholic Worker Movement is to:

Examine unfair systems, such as most forms of capitalism.

Promote workers’ rights.

Condemn the proliferation of war and weapons.

Start eco-friendly ways of making a living that are not dependent on corporations or the government.

In 1933, Day and Maurin began setting up places where people could live. These were the first “houses of hospitality.” The founders chose to live with the bare minimum, putting money and labor towards providing for others in need. Today there are over 100 houses of hospitality. Some specialize in certain services, such as housing corporate whistleblowers, or serving as soup kitchens.

Day believed in subsidiarity. Subsidiarity is a major part of Catholic Social Teaching. It is the principle that problems should be solved at the lowest level, as opposed to letting large government agencies handle every aspect of daily life. The New York City government did not approve of how many people Day allowed to live in her house of hospitality. She did not like that she was burdened with housing laws when she was just trying to run a homeless shelter. She went to court and was frustrated that she would not even be able to state her case for a long time, due to the docket being full of similarly frivolous cases.

The Canonization Controversy

Canonization is the process of becoming a saint. Dorothy Day is in the process of canonization. However, there are aspects of her life that make canonization complicated. Firstly, she had an abortion. Her books do not mention this specifically, instead referring to that time in her life as a dark one for vague reasons. She published two of her memoirs in the 1950s and 1960s when abortion was generally not mentioned except behind closed doors. What is evident is that she was pressured into having an abortion, and regretted it deeply.

For years, she thought the procedure had made her infertile. She was overjoyed when she finally became pregnant again years later. Her daughter’s name was Tamara Theresa. The father was against Catholicism, which was becoming more and more important to Day. He was also not interested in fatherhood. Day was heartbroken that she had to cut him off, but continuing the relationship also made her miserable.

Aside from the abortion, and the birth out of wedlock, there are political reasons why Day may not look like an ideal saint on paper. Her FBI record calls her a communist, and even “recommended that [Day] be considered for custodial detention in the event of a national emergency.”

Canonization Concerns From Days’ Supporters

Dorothy Day’s life was not free from controversy, making canonization complex. With that said, some who oppose her canonization are supporters of Day. Some critics of her canonization say that sainthood would sanitize her image.

The high cost of canonization is also cause for controversy. Some people believe that Day would have preferred that money be spent on the poor. Day once said, “Don’t trivialize me by trying to make me a saint.” On the one hand, this quotation can be used to show how humble Day was. On the other hand, some take the quotation at face value.

On the subject of canonization sanitizing Day’s image, there have indeed been efforts to explain away her abortion, as well as her political beliefs. Still, those who justify her canonization do make valid points.

Call for Canonization

“It is a well-known fact that Dorothy Day procured an abortion before her conversion to the Faith. She regretted it every day of her life. After her conversion from a life akin to that of the pre-converted Augustine of Hippo, she proved a stout defender of human life…I contend that her abortion should not preclude her cause…”

“It has also been noted that Dorothy Day often seemed friendly to political groups hostile to the Church, for example, communists, socialists, and anarchists. It is necessary to divide her political stances in two spheres: pre-and post-conversion. After her conversion, she was neither a member of such political groupings nor did she approve of their tactics or any denial of private property. Yet, it must be said, she often held opinions in common with them. What they held in common was a common respect for the poor and a desire for economic equity…So much were her ‘politics’ based on an ideology of nonviolence that they may be said to be apolitical.”

Cardinal John O’Conner, Catholic New York, March 16, 2000, quoting from his February 7th letter to the Holy See

O’Conner brings up Saint Augustine of Hippo because he was famously unchaste until he turned to God. He is arguably one of the most influential saints in all of Catholic theology. Like Augustine, Day wrote about chastity being difficult but important. O’Conner arguably does falter when he asserts that Day is not an anarchist, though. Day did identify as an anarchist after her conversion, specifically a Catholic anarchist.

Today, some historians classify her belief system as a form of libertarian socialism. This umbrella term applies to political views that combine socialist and anarchist beliefs. Libertarian socialists often regard state communism and capitalism as equally evil. Unlike communism, anarchism is not necessarily in opposition to Catholic beliefs.

Dorothy Day’s Legacy

Dorothy Day died in 1980, but the Catholic Worker Movement is still going strong today. The newspaper that Day founded, The Catholic Worker, is still in rotation. The hospitality houses that she started are located around the world. Day wrote eight books not including anthologies.

In 2015, Pope Francis addressed the United States Congress. He named four exceptional Americans: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Thomas Merton, and Dorothy Day.

“In these times when social concerns are so important, I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.”

Pope Francis in his address to Congress

Bibliography

Day, D., & Eichenberg, F. (1952), The long loneliness: the autobiography of Dorothy Day. HarperOne.

Day, D. (1997), Loaves and fishes: the inspiring story of the Catholic Worker movement. Reprint Edition. Orbis Books.

READ NEXT:

Radical Change: The Social Impact of the Industrial Revolution

By Rachel Knight